Au Moulin de la Galette, Madeleine

Richard Law, UTC 2026-01-01 04:21

Let's take a look at a work by the Catalan artist Ramón Casas y Carbó (1866-1932), who was born on 4 January 160 years ago – how time flies!

The painting in question is the artist's most famous work, Au Moulin de la Galette, Madeleine, which he painted in 1892, during one of his periods in Paris. It hangs currently in the Montserrat Museum, Barcelona.

The painting has also achieved a wider popularity, for the same reason that Leonardo's Mona Lisa entered the empyrean of iconic images, its enigmatic nature. Those who give it more than a passing glance are challenged to come to some conclusion on what it is 'about'. We don't want to spoil anyone's fun, but it may help if we can reduce the enigma to a manageable size.

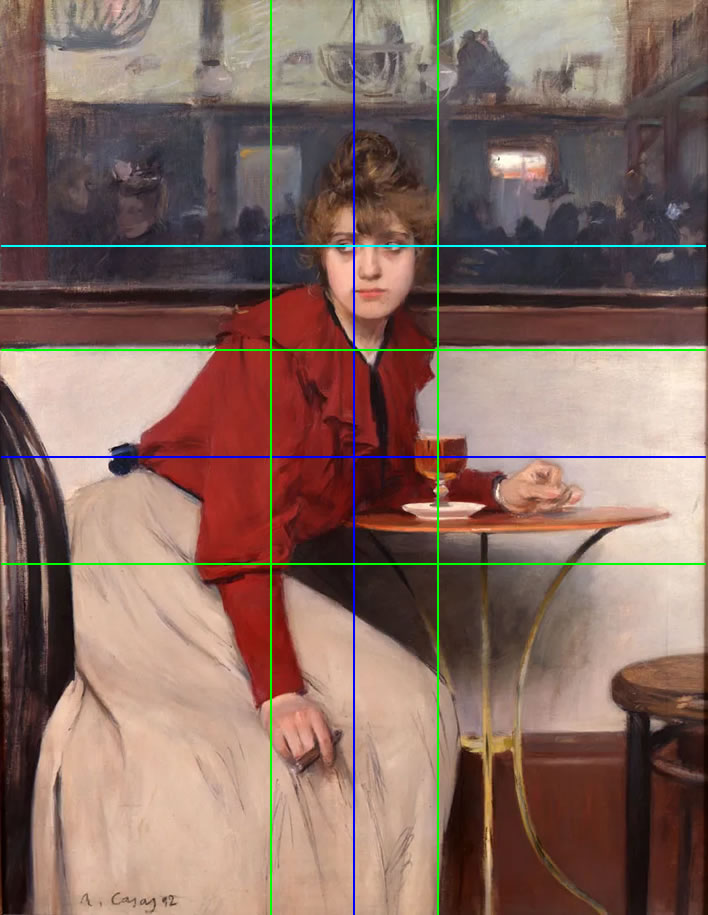

Here is an image of the painting:

Ramón Casas, Au Moulin de la Galette, Madeleine, 1892. Image: Montserrat Museum, Montserrat Monastery, Barcelona.

The observer's gaze is drawn instantly and unavoidably to Madeleine's face – and particularly the expression on her face. I won't try and describe this expression at the moment, but let's just note this initial focus.

The more carefully we look at this painting, the more we note that the picture offers layers of imagery and suggestive meaning which unfold under our gaze. Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot could spend happy hours contemplating the significance of all these elements.

But before we go deeper, let's just examine the overall composition of the painting.

Composition

Composition analysis, Au Moulin de la Galette, Madeleine. Centre lines, golden sections, eyeline Image: FoS

The figure of the young woman is posed around the horizontal and vertical centre lines of the canvas (blue). The face of a human is almost always the first priority for the gaze of another human, especially when its position is so central, but in this case the woman is also boxed in by the golden sections of the composition (green).

It is fair to say that the viewer is also possibly a little startled by the novel angularity of the pose – normally we expect our sitters to sit on chairs properly.

From there our gaze circles outwards to pick up other elements: the full glass of rosé, barely sipped; the 'relaxed clench' of Madeleine's left hand (with the hooked first finger suggestive of anxiety).

Then there is the deep red blouse – a cleverly chosen colour which asserts itself quietly, setting a mood, without distracting from the face. Then the cigar in her right hand (every popular picture needs a talking point). The objects on this level of perception are all drawn quite accurately, although not as precisely as the face and hair – the head is a very fine piece of precision painting, even down to the shadows under the eyes – 'bedtime eyes' we called them in my youth. The table and chairs are also quite realistically rendered without overwhelming precision.

However, when we look at the mirror on the wall behind her head, the previous precision has been replaced by an extremely impressionistic rendering of the scene behind us: the place is heaving with customers, many of whom are dancing.

Here is the particular part of the scene she is watching. The cyan line indicates her attention: the faces heads and shoulders of the crowd. The observer will notice – probably without noticing – that her eyes are looking to her right, whilst her head remains pointing towards us, typical when someone wants desperately to look at something without being seen to look at it.

The view in the mirror. Even after some digital tweaking, barely there. Tweak as I may, I cannot make out a male figure here. You don't think the object of Madeleine's interest could be another woman? As we shall see in a moment, Casas may have some form in this respect. Certainly Madeleine's rather butch cigar – no slender panatella for this dame – may well be a hint. The experts at the Montserrat Museum have led a sheltered life: they tell us that an image of a woman smoking a cigar would have caused a scandal back in pious Barcelona. I think the poor lambs are missing the bigger picture – and the bigger scandal.

A viewer will intuitively understand the dynamics of this pose: the rocking motion onto the left buttock, then the half-corkscrew above that; the rightwards twisting of her body that moves up from the chair, still directly in front of the table, then a twist of the waist, then up to the twist of the head and finally to the rightwards gaze of the eyes. Taking the posture as a whole, this is someone we would also intuitively understand to be watching surreptitiously. Madeleine is not a wallflower watching the crowd with detachment, she has a target.

A word about her skirt. Casas rendered the dark red blouse with some precision, although obviously not as much as the major attraction – her head and face. But the skirt has gone completely wrong. It is a sketch of a skirt, the sort of thing a painter would do as the preliminary stage.

The skirt depicted here is a simple beige fill with hardly any variation. Casas has made hardly any effort to add form, texture and folds to the textile. The best we get are some crude, sketchy hints at… something or other. 'Sketchy' is the correct word for such scribbles. 'Shamefully bad' comes to mind. This is a painting that has not yet been finished.

The experts at the Montserrat Museum noticed this too – they could hardly miss it – and believed that the work remained unfinished for a while and was then, for some reason, rapidly signed and dispatched. A nice theory, except that Casas was independently wealthy and as far as I know never had to worry about money or getting a quick sale. Perhaps someone made him an offer he could not refuse for the painting as is.

My feeling is that the skirt is unfinished because Casas never resolved the problem of how to render it. It is such a large element in the foreground of the composition that more detail in its rendering could easily distract from the face, where the action has to be. The painting's admirers don't seem to notice this, but once you have seen it, you cannot unsee it – such shoddy work lets down the rest of the painting.

The consequences of the sketchy rendering of the skirt are easy to see: the positions of Madeleine's legs are not defined, which sabotages the rendering of her posture. Presumably her left leg is the one under the table, but where is her right leg? One would assume that she is resting her right arm on it, but the missing contours leave us unsure. Given the dynamism of the pose, such things matter.

Get a room

It is interesting to contrast Casas' portrait of Madeleine with another of his paintings expressing social discomfort in the same dance hall, his Moulin de la Galette Interior, painted sometime in 1890 or 1891, perhaps a year before Madeleine.

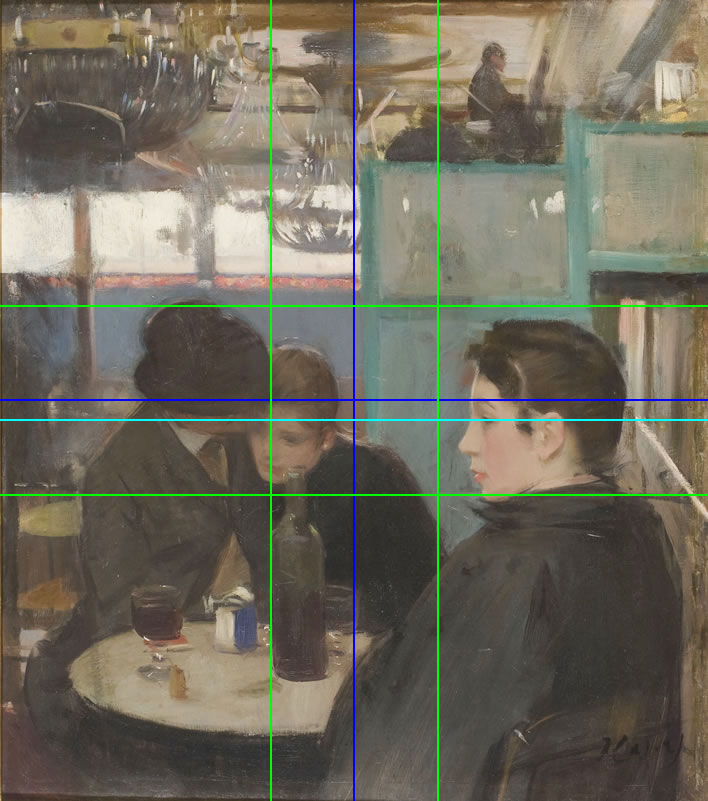

Ramón Casas, Moulin de la Galette Interior, Image: © Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona.

Just as in Madeleine, the observer's attention moves from a relatively precise rendering of the face of the woman on the right of the painting, through zones of increasingly vague impressionism.

The emotions represented are much easier to grasp than in Madeleine. Perhaps the two women are related or just friends, but we have surely all been in situations where we were the outsider fated to be unwilling witnesses of some inappropriate scene. Whether this is a seduction in progress or the rather sad-looking young lady is getting some bad news from her dominant beau doesn't matter. The main thing is that the woman on the right would certainly rather be somewhere else.

Composition analysis, Au Moulin de la Galette Interior. Centre lines, golden sections, eyeline Image: FoS

When we examine the composition of this painting, it doesn't take much brainpower to see that the vertical centre line does not unify, as it does in Madeleine, but rather separates the two fields of action: the excluded woman on the right (apart and detached) from the man and girl duo on the left (close and bundled). The heads, on the other hand, are all centred along the horizontal centre line, bounded by the two horizontal golden sections.

However, to lurid imaginations like mine the rather cropped hairstyle of the woman on the right might suggest a love interest between the two women – this is the City of Light of the 1890s, after all – which might explain the froideur towards the chap putting the moves on her girl.

He is shown as being merely some faceless creep, some Lothario from Central Casting. The woman on the right, despite her tetchy embarrassment, cuts a dominant figure; the girl seems much more submissive, particularly with some man leaning down on her. She shows no happiness or pleasure at these attentions – in her eyes there is only fear and loathing.

The woman on the right has detached herself from the drama opposite her by doing what we all do in such situations: adopting a fixed stare feigning interest in some distant scene. Is that glass her glass, that has been drunk dry? Is that the girl's glass, also empty, that we can just see behind the bottle? The glass in front of the invasive creep is almost full, suggesting that he is a recent arrival and that the two women had been getting along fine until he arrived and descended on the young hottie at the apex of the love triangle. No wonder the woman on the right is looking bleak.

What can she do but wait the situation out? Were she a man and the girlfriend was being worked on by another man, the outcome would be quite different. We are only fifteen years after George Sand (1804-1876) died, but it was still tricky for a woman to deal with a male pest.

In passing, we note that, once again, Casas has rendered the dress of the woman on the right very poorly – a scruffy, dark-grey splodge. The divide between impressionistic and plain scruffy is a fine one, which Casas stepped over here. It is one quite legitimate thing to render the distant orchestra with a few impressionist dabs, it is another quite misjudged thing to clothe the protagonist of the picture in a hiker's black poncho. Unless, of course, the lack of female frippery is another clue for us.

Jalousie

The model for Casas' Madeleine was Madeleine Boisguillaime. She was popular with a number of well-known artists at the time. The experts at the Montserrat Museum have an old photograph of another of Casas' paintings entitled Jalousie, from 1891, the timespan in which we are interested.

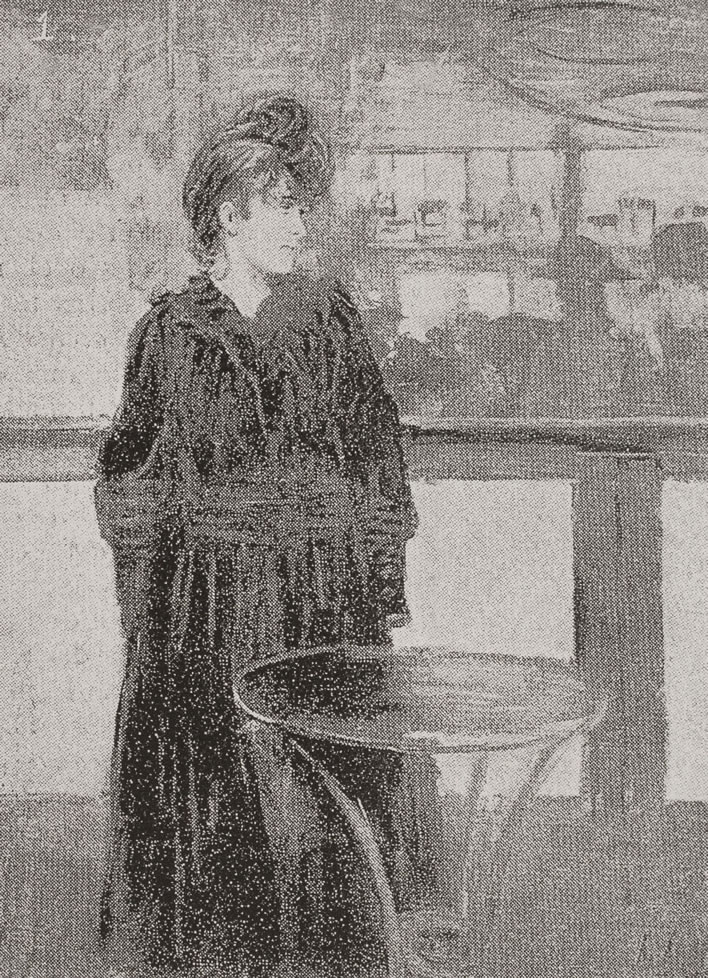

Ramón Casas, Jalousie, 1891 Image: Taken from a contemporary photo. Current location and ownership unknown.

The model for this painting was definitely also Madeleine Boisguillaime, with the same piled-up hairstyle, a dress with a similar top. There is the same table and the same mirror, only this time she is standing and looking directly at someone. From what we see in the mirror, that 'someone' appears to be a couple on the dance floor. Helped by the unambigous title the interpretation of the situation is made easy.

However, the image is much inferior to the later Madeleine, particularly in its defective composition: her face, which represents the main event in the painting, is off at the top left. Because the face is half-profile, her expression – the main event – is unclear. She is on or close to a vertical golden section, but the first thing the viewer sees is a bistro table, then a dress. Here the man of the dancing couple is rendered more explicitly than in the later works, where the man is smudged into insignificance.

Perhaps that is also a clue for us sleuths. In Madeleine, the couple (if it is a couple) who are the object of Madeleine's attention are rendered very unequally, the woman much clearer than the man, who has to make do with being a smudge. The woman, on the other hand is quite well defined, meaning that she is the focus of Madeleine's gaze, the man, as in the Interior, may be yet another faceless creep scouting for girls in Le Moulin.

In sum, both Madeleine and Interior, for those with eyes to see, are undoubtably painted in the Sapphic mood.

The Sapphic mood

Now for some real speculation. Once I became aware of the possible lesbian aspects of these paintings of Casas', the famous Fragment 31 of Sappho came to mind (all we have of Sappho's poetry are fragments; number 31 happens to be the longest one). In this fragment, Sappho observes a man sitting next to a girl who is the current object of desire of the poet. We do not know what the context is, or who the girl or the man are.

Modern translations and interpretations find no jealousy in this text, rather just hyperbolic admiration for the girl. In Casas' time the poem was (probably) interpreted differently, sometimes as showing jealously, probably more correctly showing the poet's envy of the man sitting next to the girl. If Casas knew of Fragment 31, this would probably be the interpretation with which he was familiar. The poem describes an emotional white-knuckle ride with which modern women can identify and which suggests that the Greeks would have little to learn from us neurotic moderns. Certainly, the paintings we have looked at here can serve as a good illustration of Sappho's love-trauma.

He seems to me equal to gods that man

whoever he is who opposite you

sits and listens close

to your sweet speaking

and lovely laughing — oh it

puts the heart in my chest on wings

for when I look at you, even a moment, no speaking

is left in me. […]

A fragment of a fine translation by Anne Carson (2003), an example of the 'modern' sense of Fragment 31. From IF NOT, WINTER: FRAGMENTS OF SAPPHO by Sappho, translated by Anne Carson, copyright © 2002 by Anne Carson.

What I have called the 'Sapphic mood' of the two paintings is not just a periphrastic detour around the word 'lesbian', it expresses my feeling that Casas may have had the very famous Sapphic Fragment 31 in his mind, in the sense that it was interpreted in his time. As I have to say so often on this website, I have no evidence for this.

This is not the place for an extended essay on the place of Sappho and her fragments in the culture of fin de siècle France and particularly Paris, a.k.a Sodom and Gomorrah. She was in the air: Verlaine wrote a (somewhat hysterical) poem about her; Baudelaire ('Lesbos'); Proust scatters allusions to Sappho in À la recherche du temps perdu; Swinburne representing Britain (‘Sapphics’) caught the mood; even Tennyson had a dabble. If we were aiming at a thorough understanding we would have to consider Sappho's image in Spanish culture of the same period, something that is far above my paygrade. Modern treatments of Sappho are infested with feminist and queer theorising, so it will not be simple to recover the fin de siècle understanding of Fragment 31 from beneath a layer of contemporary stodge.

Casas took the concept and his model from Jalousie and improved it greatly for Madeleine: the face is now central and full frontal, the pose interestingly angular rather than some woman just standing around. He produced a good painting that deserves its popularity. It is just a pity that a little bit more attention to the embarassingly poorly rendered skirt and (perhaps) a little bit more definition of the object of Madeleine's gaze would have transformed this good painting into a great painting.

Ramón Casas, Self-portrait (1908). Head, hat and pipe carefully worked in detail, the rest acceptably sketchy. Image: Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!