Schubert's syphilis revisited (yet again)

Posted on UTC 2026-01-18 09:12

Mise-en-scène

Sooner or later, those, like me, who stumble around in historical matters get bitten by the 'if only' bug. In times before the great scientific and particularly medical revolutions of the twentieth century, doctoring was, at best, harmless mumbo-jumbo, but at worst, a painful and dehumanising passage to the gaping coffin. 'Do no harm', states the doctor's oath, full of irony.

Within the very limited scope of this website we have come across many medical interventions that have had us shouting 'No!' at our computer screens. At the futile but harmless end of the spectrum, we recall the Hapsburg Emperor Joseph II being prescribed porridge for the lung disease that would shortly finish him off; his successor the Emperor Leopold II, who, had he survived, might have spared Austria and Europe many of the horrors of the Napoleonic Age and the disaster that was his successor Franz, had a simple throat infection which spread to his belly and overwhelmed his body; we recall Friedrich Rückert, devastated by the deaths of his two youngest children, remembering the leeches feeding on them or suddenly noticing the many empty medicine bottles lined up on the windowsill, remembering how he had to bully his little dying daughter into swallowing this bitter filth, observing the quasi-Satanic astrological symbols on their labels and reflecting on the demonic spirits within; Heloise Höchner's weakling firstborn was accompanied to his exitus by baths in river water and finally an immersion in ox-stomach bouillon. If only. We moderns are blessed with more knowledge but cursed to have to watch helplessly as our forebears, humans like us, do stupid, ignorant and fatal things from the best motives.

And so we come to Schubert's place in this sad parade. We now know, beyond any reasonable doubt, that he and his bosom-buddy Schober were infected with syphilis towards the end of 1822 and spent 1823 being 'cured' of it. We know this despite the discretion that surrounded this sexually transmitted disease – no innocent toilet seats were involved in the acquisition of this bacterium. We know nowadays that in about three-quarters of cases the infection runs its course over a few months and then the symptoms and the bacteria disappear. The fate of those in the unlucky quarter is, at its worst, horrible.

Now that we know just how toxic mercury is (and how long-term that toxicity can be), slathering it over syphilitics as a cure seems completely reprehensible. Well, yes and no: we should remember that Paul Ehrlich's discovery around 1907 of Salvarsan – an arsenical compound that became the first effective treatment for syphilis – was the result of his systematic hunt among poisons for one that was more poisonous to the bacterium than it was to the patient. A century or so later we have chemotherapy.

We should also be aware that the fear engendered by the heavy metals these days, mercury and lead in particular, is a relatively recent phenomenon.

In the early sixties, in the school chemistry lab, we frequently passed the time playing mercury blow-football – a good-sized blob of mercury on the bench, a few bits of chopped up rubber tube and away you go. Sooner or later the blob would roll off the bench and disappear into the cracks in the wood floor. After sensitive analytical equipment began to be produced, the alarm over a few parts-per-billion here and there became too loud to ignore. The lead waterpipes of my childhood were state of the art. These days my old school would be closed down for months while a hazmat-suited team laboured within.

There is no reason to test Schubert's hair for lead. This seems to be just unthinking environmental panic. An evening drinking wine in the pub or at a Heuriger will keep your body supplied with all the lead it can cope with. For centuries the Austrian authorities tried to keep wine, beer and spirits drinkable, an almost impossible task in the days before chemical analysis could be carried out.

Before continuing, we must repeat ten times, 'Schubert did not die of syphilis', he died of typhoid fever (as his mother had done).

Quite understandably, Schubert suffered from hypochondria after his 1823 brush with syphilis, but it seems that he (and Schober) were among the lucky ones that survived the infection – and survived its treatment, too. Schubert seems to have laid low for a while, moved his residence and taken to wearing a wig (although I am not completely convinced about this last point); Schober took himself off to join a theatre troupe in Breslau, in which wig-wearing was part of the job and possibly many of his colleagues had had a brush with the disease.

The outstanding questions are simple to pose but tricky to answer. Did Schubert recover? Were his afflictions after 1823 leftovers from the 1823 infection, or leftovers from the treatment, or just simple hypochondria?

Headaches, his main complaint, are only to be expected in someone like Schubert, desperately short-sighted, wearing spectacles that are anything but optimal, composing long hours by candlelight.

In the years between 1823 and his death in 1828 his 'circle of friends' had disintegrated as they married, moved away and followed their careers. He was attempting by force of talent to make his way through a feudal society that in many respects despised him. In doing this he had only his own strength of character to rely on. Schubert was never a chick magnet, though there are plenty of hints that he would have liked to share his life with a good woman. But what good woman wants an undersized, syphilitic depressive with a hand-to-mouth income in her life? We are not surprised to learn that he liked the odd drink.

We have the impression that, apart from occasional highlights – the success of his one and only concert, for example – Schubert was suffering from a severe clinical depression. He had the great good fortune at least that no modern doctors were around to get him hooked on antidepressants. In such a depressed state, many are the demons that come to visit you – hypochondria is only one of them, a compromised immune system is another.

In 1828, without the distractions he used to have from his 'circle of friends', he dedicated himself to a life of manic activity, whether composing or long-distance walking. The simplest explanation for his succumbing to typhoid fever might even be just 'general exhaustion'.

One night with Venus

So let's move on to the cause of our present meanderings, the paper One night with Venus, a lifetime with mercury, which was published on 29 April 2025 [Fischer, L., Hann, S., Amory, C. et al. 'One night with Venus, a lifetime with mercury'. Wien Klin Wochenschr 137, 438–445 (2025). DOI].

A paper that could confirm with scientific rigour Schubert's syphilis infection in 1822/23 and an associated mercury treatment (the usual nostrum of the time) would be a very welcome addition to the Schubert literature.

Unfortunately – and I write that with great regret – this paper is not it. The title is great (wish I had thought of it), the fact that it is open access is great, but the rest is a disappointment. Let's go through it step by step.

Provenance of the samples

The paper describes an analysis of some samples of Schubert's hair. The first hurdle the authors have to jump is the attribution of the source of the hairs they use and the date of their cutting. I am not really doubting the provenance of their samples; I am not doubting that the curls in Herr Hofbauer's possession are from Schubert for example, but some documentary evidence for this provenance is needed in a purportedly scientific paper – Vertrauen ist gut, Kontrolle ist besser.

We are presented with two assumptions: 1) this hair is from Franz Schubert and 2) this hair was taken more or less immediately post-mortem.

It was indeed a widespread habit to snip a lock of hair from the corpse; it was also a even more widespread habit to snip a lock of hair from the living loved one – hence the 'locket' to keep it in. [Although the term comes from the catch, the 'lock', used to secure the chamber, not the lock of hair it usually contains. OED]

We accept that historical attributions are often anything but secure and investigators have usually to deal with what they have got, but in the present case, all the findings of the study depend on the attribution of provenance that is so casually assumed. If that is wrong, the rest is pointless.

Curls of Franz Schubert (Private possession of Raimund Hofbauer, Kritzendorf, Lower Austria) Image: Fischer et al.

Of the provenance of the ringlet of hair in the possession of Herr Hofbauer, the researchers write:

An inscription, written in German current handwriting (style approximately from 1850) declared the authenticity: “For Mrs. Mitzi Schubert, retired teacher, curl from Fr. Schubert. By kindness —a synonym for delivered by messenger at the time” [translated].

Well, we are not told who the sender was, which is a critical omission in the chain of custody. Herr Hofbauer could certainly clear this up, but it something the authors should have done. Perhaps it is in the missing 'Supplementary Information'. Nor do we know the date of the transmission. 'German current handwriting' is another problem. Versions of Deutsche Kurrentschrift were in use for centuries and there were many regional variants, so 'style approximately from 1850' does not satisfy my curiosity. An illustration of this important document would have been helpful and/or, even better, some form of attest from a recognized expert. '[D]eclared the authenticity' – well, not really.

Leaving the erratic punctuation of the translation to one side, your author stumbled over the word 'kindness', here used presumably for some kind of postal service.

I have never heard of a 'kindness' in this regard. Unfortunately, the authors do not supply the German original of the text, which is remiss of them – on this website we always try as far as possible to give the source of translations, even at the risk of seeming affected. Thus, some guesswork is required. I presume this is an erroneous translation of la diligence, the name given to the widespread – though expensive – means at the time for what would now be called express post [Eilpost]. The French term diligence became used à cause de sa rapidité, Larousse tells us. The initial meaning of diligence, promptitude, rapidité efficace, has now been extended both in the Francophone and Anglophone worlds to include empressement, zèle: expedition, thoroughness. The impeccably useful DWDS even has a nice illustration of a Diligence coach. The OED regards diligence in the meaning of speed or despatch to be obsolete in English.

The cackhandedness of this translation does not inspire confidence in the rest of the paper.

Misreading sources

In yet another misstep, the researchers tell us that:

Contrary to the assumption that Schubert’s hair had fallen out during sickness and respective treatment, reports describe that his “rather large, round and coarse head was surrounded by brown, luxuriantly sprouting curly hair” and “full brown, naturally curling hair”.

Yet another reason for the knowledgeable to stumble. This statement is simply not correct. The source quoted is an entry from Hilmar's Schubert Lexikon (1997) and describes the normal appearance of Schubert's hair. If the authors of the paper (who are all scientists and should know better) had bothered to read further in their chosen source they would have come across the statement

Einige Zeit lang trug Schubert allerdings aufgrund seiner Krankheit und das dadurch bedingten Haarausfalles eine Perücke.

'For a while, however, as a result of an illness, the treatment of which had caused hair loss, Schubert wore a wig'. Translated and improved, since it was not the illness but its treatment that caused the hair loss.

Supplementary Information incomplete

The article tells readers that 'More information can be found in the supplementary section'. Unfortunately, it can't be found there, unless, unlike the rest of the article (which is open source), the supplementary information is hidden behind a subscriber paywall.

We learn from the article that they have used hair samples from two sources: Herr Raimund Hofbauer (a Schubert descendant) and the Ignaz Weinmann collection. We presume that the hair samples taken during the exhumation of 1863 are too degraded to be of use, but this is not stated specifically.

Photograph of the medallion from the Ignaz Weinmann collection with Franz Schubert's hair. Light-colored bronze, diameter 64 mm, circular engraving. Image: Fischer et al.

Categorizing the samples

So far, so good. But then in the description of the handling and labelling of the samples the reader is left completely baffled. From the source Hofbauer, for example:

A few single hairs were removed with sterile and pre-annealed tweezers, transferred into small paper envelopes and labelled accordingly: Schubert A1.W, Schubert A2.W, Schubert A3.W, Schubert B and Schubert B 1.W.

To which we can only ask: How many is 'a few'? and what do these designations represent? Then:

Two single hairs of the loose strands of approximately 3 and 4 cm in length were removed from the medallion individually using sterile and annealed splinter tweezers and subsequently transferred in paper envelopes labelled as follows: Schubert C 1—tox and Schubert C 2—DNA.

Don't bother trying to memorise the names of these samples, they are never used again. From now on we have hair A, hair B and hair C, and a little later hair segments A‑S, B‑S and C‑S – and sometimes other variants which I cannot be bothered to enumerate.

Already confused, the reader has now to trudge through a lot of hypertech-talk about mitochondrial (mt) DNA analysis, hair analysis by LA-ICP-SFMS and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Which is fair enough, it is what the paper is about – it's not the author's fault that I do not understand a word of this apart from occasional highlights such as 'Pritt non-permanent double-sided tape'.

So let's have a look at what emerges from this complexity.

Interpreting the results

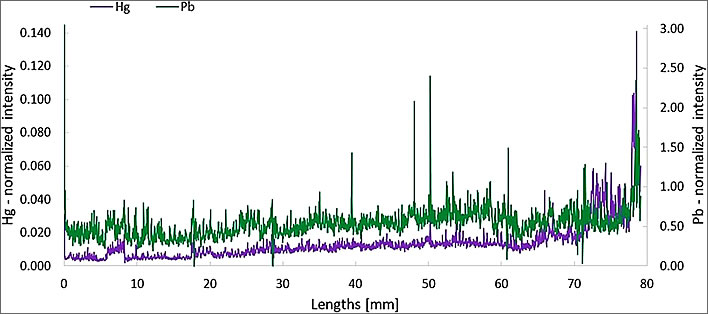

Variations of relative concentrations (34S normalized intensities) of Hg and Pb in a hair sample of Franz Schubert (Schubert A 3.W). The hair sample was ablated from close to the root (0 mm) to the end of the hair (surface scan), reflecting exposure of toxic metals during approximately the last 8 months of his life. Image: Fischer et al.

In order to understand these results you have to know that on the x-axis (length), zero is the hair root and the value on the right is the length of the hair. I find it difficult to imagine that there is a hair root still present on a hair that was clipped off post-mortem. Perhaps they don't mean the hair root as such, but rather the end of the hair nearest the scalp. Never mind, onwards we go. We are told (rather obliquely) that this length scale represents between five and eight months of hair growth. Assuming eight months, the scale therefore runs left to right from 19 November 1828, the moment of Schubert's death, to (say) eight months before, that is March 1828. In this respect, Schubert fans will think of Schubert's first and last concert, on 26 March 1828 – except eight months is just guesswork, remember. The spike around the 80mm mark may be inconvenient and thus can be dismissed as an outlier – possibly. There are no error bars (something I find quite shocking, actually), so we have no idea whether the variations or the overall slight slope on the graph are significant. I am not sure which curve is Hg and which is Pb. From the other graphs it seems that Hg is purple and Pb is green. If we discard the final spikes we are forced to conclude that nothing changed in this period and only the absolute value is relevant.

About seven years ago I went into some detail about the events of the months leading up to Schubert's death. There was nothing in particular from that time that aligns with the mercury timeline. Until the first week in November, when the typhoid fever smote him, he had been manically active in work and in leisure.

The mercury timeline has anyway to be treated with caution. As the researchers point out, high mercury levels can be caused by the 'release of bioaccumulated mercury from body tissues into the bloodstream and incorporation into the hair matrix over many years'. In other words, the values measured could reflect mercury that was acquired possibly 'many years' beforehand, which means that there is ipso facto no relationship between this plot and Schubert's 'lived experience', as we call it now. Being subversively reductive, I could argue that a few datapoints would have been enough to establish the presence of mercury in Schubert's hair, which would have had the advantage of not misleading observers into thinking that this was a plot of contemporary mercury pollution.

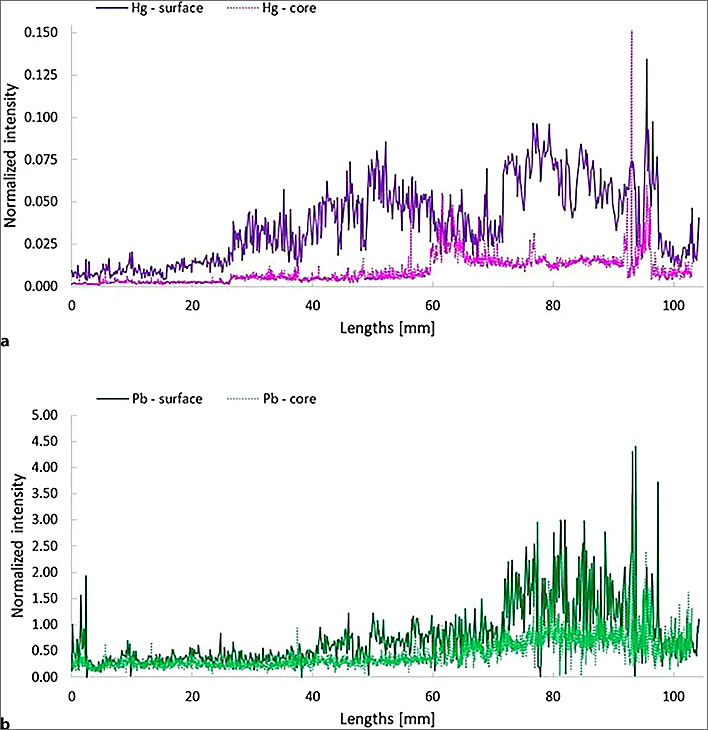

Variations of relative concentrations (34S normalized intensities) of Hg (a) and Pb (b) in the surface (cuticle) and the core of a hair sample of Franz Schubert (Schubert B). The hair sample was ablated from close to the root (0 mm) to the end of the hair, whereas the second scan was performed with an offset of the z‑axis (10 µm) to laser scan the inner part of the hair Image: Fischer et al.

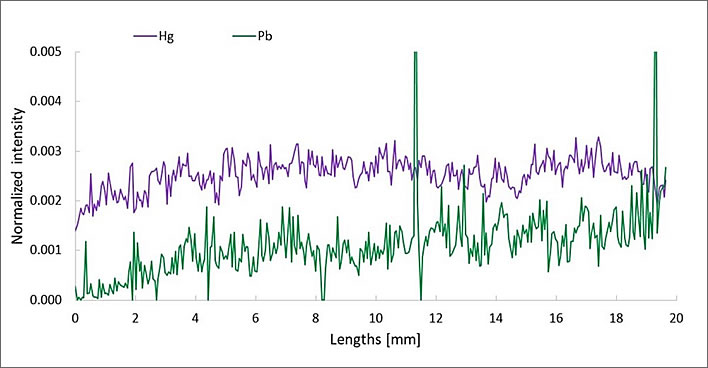

Figure S1: Relative concentrations (34S normalized intensities) of heavy metals in a single hair (cuticula) of a male non-smoking individual. The hair sample was ablated from the root (at 0 mm) to the end of the hair. Image: Fischer et al.

The results from the normal person (mysteriously consigned to the section 'Supplementary Information') are plotted to a much larger scale – the y-axis of the 'normalized intensity' runs from 0.000 to 0.005. The x-axis of the length is also much shorter than that of the Schubert samples (20mm instead of 80..100mm), meaning that for the normal person the intensity is at least a factor of 10 smaller than Schubert's levels and the time span represents only three to four weeks of growth. The researchers could have been kind to the weary brains of their readers and presented all their results on the same scales, since this is in effect the crux of their argument.

Improper comparison sample

Comparing Schubert's results with those from a contemporary male strikes me as being a waste of time. The environmental differences between the 1820s and the present are so enormous and multifactorial that a comparison of the two is both meaningless and misleading. The only relevant comparison would have been with hair samples from several of Schubert's contemporaries. Of course this would be more difficult, but I am sure that Austria is not short of post-mortem hair clippings from the early nineteenth century.

I had to read the researchers' concluding remarks a few times before I was able to decipher what they were saying. Despite my efforts, I am not convinced that I have understood their statement. The reader must judge:

The continuous but on average 50-fold increase of the relative mercury concentration and the up to 2000-fold increase of the relative lead concentration in Schubert’s hair in the last 10 months before his death indicate a massive heavy metal exposition years before with subsequent long-term excretion.

Apart from not making any sense in general, the difficulty with this screwed up statement seems to be that they are using the word 'increase' when in fact they mean the word 'difference'. According to their own data, Schubert's 'pollution' did not increase in the months before his demise, if anything, it decreased. The alarming '50-fold' and '2000-fold' statements are in relation to the levels found in a modern non-smoker (I think). This level of drama is achieved by taking the pronounced spikes which, we were told, were treated as outliers and ignored.

Pipe smoking

'Presumably, Franz Schubert occasionally smoked a pipe', they tell us. Not 'occasionally' – Schubert was a passionate pipe smoker. One of his earliest residences were rooms rented out by a lady running a tobacco shop. 'Presumably' and 'occasionally' are out of place here.

Mercury release confusion

The researchers conclude that 'the significantly increased mercury and lead concentrations in Schubert’s scalp hair can be most likely explained by a previous syphilis treatment' – which leaves us wondering when this treatment took place. In 1823 almost certainly, but did Schubert or his doctor help things along with top-up medication? Because this is the problem they have with this interpretation.

If we accept their statement that body tissue can release mercury over a number of years, then how can we understand the situation around, say, six months before Schubert's death. The (not very explicit) suggestion seems to be that mercury has been leaking from its storage in Schubert's body since 1823: 'Constant release of bioaccumulated mercury from body tissues into the bloodstream and incorporation into the hair matrix over many years could explain the elevated relative concentrations in the hair of Franz Schubert'.

Well, perhaps, but a few numbers would be more convincing. We have this confusion because of yet another non-barking dog in this paper: some evidence-based estimate of the 'decay-time', or 'release-time' if you prefer, of mercury stored in human tissue and its migration into hair. 'Up to 20 years' is just waffle. Someone, somewhere must have done some work on this.

Schubert the self-medicating hypochondriac

If we accept these results – only a specialist in the technique could dispute them – we find that Schubert had a high level of mercury and lead in his system five to eight months before he died. But note, too, that this is 1828 and we are therefore a long way from 1823 and Schubert's treatment. The results, therefore, say nothing about the composer's syphilis attack and his treatment, they suggest that Schubert, because of his general hypochondria or his headaches, had been self-medicating. If so, we don't know how long he had been doing this.

My own, layman's suggestion, is that the hypochondriac Schubert, convinced his headaches were symptoms of lingering syphilis, was self-medicating with one or other of the many mercury preparations that were freely available at the time. Perhaps he felt a bit better after the success of his concert and stopped treatment – who knows?

The dapper Schubert's topper

One further thing occurs to me: Mercury was a common ingredient of many medications and was present in many households. It was also used in the preparation of felt for hatmaking right up to about the middle of the twentieth century. The effects of that mercury on hatmakers have been memorialised in the phrase 'mad as a hatter', which readers of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland can also confirm.

Schubert's fine top-hat may have been medicating him whether he wanted it or not. Some commenters attributed the large number of infant deaths in Elisabeth Schubert, Franz's mother, to her presumed former occupation as a hat-maker. Applying Occam's razor, though, the living conditions in the Schubert school, the daily cocktail of child-borne bacteria and viruses there and her long drudgery and possibly poor diet were bad enough to cause any number of miscarriages and infant deaths, without the added involvement of mercury.

Some Schubert toppers

Schubert seated in Atzenbrugg, his top-hat by his side.

Schubert caricature.

Schubert caricature.

Schubert in Atzenbrugg, on foot, far left.

The dapper Schubert's topper was his permanent companion out of doors, even at relatively informal times. The testimonies of those who knew him note that Schubert was always very correctly dressed. We can easily imagine, for example, Schuberts' hair in the mercury-laden steam bath under that topper on his three-day walking tour in early October 1828 to visit Haydn's grave in Eisenstadt.

Who knows? The researchers note that:

…the relative concentrations of mercury and lead were higher in the surface (cuticle) than in the core of the hair samples and vary similarly over time. Lower metal concentrations in the core compared to the cuticle are in accordance with previous findings [34]; however, the reason for this peculiarity remains unclear.

My layman's guess might be that the presence of more mercury on the outer sheaths of the hairs than on the inner cores would suggest that the mercury was not coming coming from Schubert's body but from an externality – such as a fine top-hat or even an exquisite gentleman's pomade! In 1823 (not in these graphs) wig-wearer Schubert was probably sprinkling all kinds of things on his head to keep the lice away. Ah, those were the days!

Conclusion

So, summa summarum, this paper shows what happens when six – six! – scientists try to change a lightbulb, without having a Schubert scholar, or even a plain old Austrian historian (there are a lot of them around) on the team – and if not in the team then at least part of the peer review process. The peer review was probably done by science specialists who focussed on the procedural aspects of the investigation – for example, the use of 'Pritt non-permanent double-sided tape'. As a result, this paper solves nothing and just throws up additional problems – even the conclusion that we all expected, that Schubert was treated for syphilis with mercury in 1823 is not actually supported by the evidence produced. To do that we need control samples from the hair of one or more Schubert contemporaries who never caught syphilis.

A great pity, but that's how it is. Sapperlot!

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!