Greenwich Dump Time

Richard Law, UTC 2015-09-15 17:07

Those of us older than fifty will probably still remember the town gasworks. The imposing gasometers, dingy brick buildings with dirty, yellowing glass in small windows. But above all, the smell.

Who can forget that strange rotten egg and cat pee smell? For more than a century these sulphurous devil’s kitchens were one of the main motors of industrial Britain. They took coal and produced gas, coke and coal tar along with scores of useful and useless substances.

And what substances these were! Benzene and naphtha, phenols, ammonia, cyanides, sulphur compounds, heavy metals and the cocktail that is coal tar itself. Many of the larger gasworks also went in for the production of related chemicals: sulphuric acid, ammonium sulphate fertiliser. Anything left over from the production processes was dumped, usually on site – spent lime and oxide, clinker and clinker waste, and unused coal and coke. These substances are all toxic, many corrosive, and many are known or suspected to be carcinogens, mutagens, irritants or sensitisers.

Nowadays, when we can detect chemicals in concentrations of a few parts per billion, when we worry that the odd whiff of unleaded petrol whilst we’re filling the tank might finish us off, we can only wonder at the hardiness of previous generations. Parts per billion? We’re talking bucketfuls here.

Every town of any size had its gasworks, but from the moment that natural gas came along in the sixties the gasworks were doomed. Most fell into dilapidation, their tar and waste dumps abandoned, some were redeveloped.

One particular gasworks, one of the biggest in Europe, went on to become the site of the Millennium Dome.

Loading pitch at Greenwich Gasworks (date unknown). Pitch is the leftover after four distillations.

© National Maritime Museum, London.

East Greenwich Gasworks seen from the backyards of houses on Greenfell Street (date unknown)

© National Maritime Museum, London.

Remediation: Seven maids with seven mops

Cleaning up this monster would be a challenge. In a House of Commons written answer 1998, Richard Caborn, at that time Minister for the Regions, Regeneration and Planning at the Department of the Environment stated that:

The depth of contamination on the site to be occupied by the Millennium Dome varied widely. The majority of contamination was contained within the surface layer, which varied between 2 and 4 metres in depth. In isolated instances the contamination extended up to a maximum of 14 metres. The treatment applied to each part of the site depended on the type and depth of the contamination. No part of the site was treated to a depth of less than 2 metres and in places the treatment extended to 14 metres.

Well, that’s all right then. But, hang on, what does he mean by ‘treatment’?

Whatever it was it had been ‘approved by both the Environment Agency and the London Borough of Greenwich and [was] consistent with Government policy on the treatment of contaminated land.’

We can probably overlook whatever environmental opinion the London Borough of Greenwich expressed in this respect. It is clearly unreasonable to expect a Labour controlled council being offered more than half a billion pounds of ‘regeneration’ by a Labour government to spend much time wondering what to do with the old topsoil.

The Environment Agency, although hardly independent of government, should be a different matter. Years later, loaded up with European standards and norms, it was bristling with advice, guidelines and regulations concerning contaminated land. There’s even a special word, ‘remediation’ – quite as horrible as ‘gasometer’ was in its time – to describe the cleaning up process.

Putting a lid on it

After a bit of textual deconstruction, the Environment Agency’s current advice still seems to mean, most of the time, ‘dump the stuff in a deep hole somewhere’. There is indeed a lot of work being done on the technologies for processing such material. Unfortunately, although such processing can work well on a bucketful of well-defined contaminants of a single type, it is completely impracticable on millions of cubic metres of gasworks cocktail. Even just getting men in spacesuits to shovel the contaminated stuff up, let alone treat it, is usually more expensive than most sites could ever be worth.

What was Caborn trying to imply by ‘treatment’? Even now, a lot of the literature tells you how to spot contaminated land, how to assess it and the horrors that might be present in it. There’s almost nothing on what to do with it, apart from – you guessed it, scrape it up and dump it in a big hole somewhere. ‘Treatment’ in any normal sense of the word was never an option.

In 1997, as now, the usual strategy was ‘containment’. Here’s the executive summary for ‘containment’: Instead of having to shovel all the muck up and dump it in dark holes, just scrape a bit of the top off, dump that in a dark hole, put something down on the stuff that’s left behind to stop the smell coming up, and pour a bit of concrete over it, or mix cement in with it, or just bury it under some fresh stuff. You have to scrape a bit of the surface off, because the extra weight of the capping you put down will, over time, squeeze the gunge outwards in all directions. Those of a nervous disposition with public money to spend also build barriers around the area to stop such sideways migration.

Large areas of the Docklands development are resting on such containments, for example the Winsor Park Estate in Beckton and Thames Barrier Park, Woolwich.

Becton, like Greenwich, housed one of the largest gasworks in Europe, with a lot of related gunge-boiling going on. As the London Docklands Development Corporation itself notes:

The waste products were to depths of four metres and included substances which are both toxic and carcinogenic even at very low concentrations.

The ‘containment’ used in Becton didn’t involve carting any of this stuff away, which would have cost money and held things up, but just a ‘barrier’ of ‘a minimum of a metre of clean imported material’.

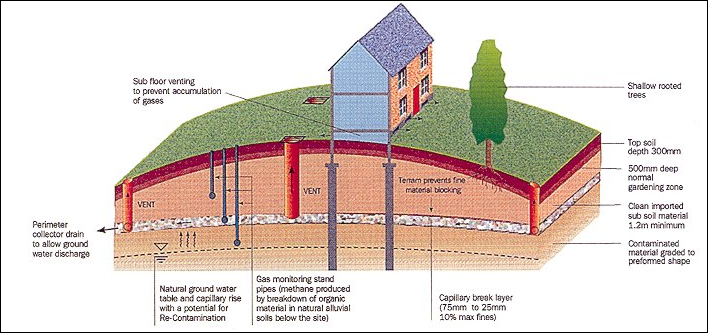

The capping technique used at the Winsor Park Estate on the site of Beckton Gasworks.

In practice this turns out to be an inch or so of gravel to stop seepage upwards, a metre of clean subsoil topped off with half a metre of ‘gardening zone’ and a daffodil bulb’s worth of topsoil. Then come the houses, complete with ‘sub-floor venting’ to prevent the gases building up. Looking out from these houses you will gaze upon ‘shallow rooted trees’ and various discreetly sited gas monitoring standpipes and gas vents. Dig down the height of a man and you have found Becton gasworks.

At least Becton’s muck stayed where it was. What happened on the Dome site?

Off site, out of sight, out of mind

It had to be done quickly, since nothing else could start until the site had been cleared and 31st December 1999 was no moveable feast. There was not much scope for finesse. According to a technical analysis of the preparation of the site in the journal ‘Land Contamination and Reclamation’, more than 200 000 cubic metres of contaminated material were excavated and trundled off to dumps. A further 30 000 cubic metres of material were ‘washed’ and replaced.

Well, I’m afraid it’s back-of-an-envelope time. The ‘Millennium Experience’ site is 81 hectares. Caborn’s tells us that ‘no part of the site was treated to a depth of less than 2 metres’ so let’s assume an average depth of contamination of three metres. The quantity of earth needing to be removed is therefore nearly two and a half million cubic metres. If seven maids with seven mops…

But if they ‘only’ removed 200 000 cubic metres then the average depth of the scrape was just 25 cm (10 inches). Not very much in terms of the scale of the problem, but nevertheless still well over ten thousand lorry loads. Don’t forget, though, that the full Greenwich Peninsula site is really 119 hectares, so we can assume that most of the rest wasn’t touched.

So Caborn’s statement was nonsense. And where was this ‘treatment’, this poisonous scraping of the worst, the top 25 cm dumped? Answer: all over the place.

The late Sir Raymond Powell extracted some details from Angela Eagle in May 1998. She revealed that the scrapings were transported by three ‘main’ haulage companies and dumped in 15 landfill sites spread around nine counties: Bedfordshire (2), Buckinghamshire (2), Essex, Hertfordshire (2), Kent, Middlesex, Northamptonshire (3), Surrey (2), Warwickshire.

She added ‘There is no statutory requirement for consultation with local residents.’

In June of 1998 the Government assured their citizens once more that

…all the sites used have been licensed by the relevant authority and are suitable for the material being disposed there.

So tough luck Stewartby, Brogborough, Calvert, Gerrard’s Cross, South Hornchurch, Ware (2), St. Mary Hod, Harmondsworth, Welcon, Cold Ashby, Collingtree, Nutfield, Thorpe and Kilsbury.

Learning by doing

Now what did all this scraping, dumping and driving around cost? In 1998 English Partnerships, the public-private partnership responsible for the Greenwich Peninsula project told us that ‘some £180m has been invested in the cleaning and preparation of the site’ – well that’s taking things seriously, isn’t it? Unfortunately, we have a few more conjunctions to get past: ‘and in the subsequent provision of a power supply, pumping station, water treatment plant, new drainage, the construction of the new access roads, the widening of the A102(M) and hard landscaping.’

In contrast, Edmund Nuttall Ltd, the company that did the cleaning up, say the contract was worth £25m. Put on the spot by Sir Raymond Powell, Ms Eagle admitted that ‘£8.2m was spent on removal and disposal of which an estimated £6m was a cost to Government funds.’ Even taking the £25m as our base, only 3% of the cost of the Millennium Experience was spent on the uncool task of cleaning up the poisonous legacy of this bit of Britannia.

British Gas, the original owners of the site, had been under a legal obligation to clean up their mess before they could sell the site. They claim the clean-up cost them £21m – apparently a part of Nuttal’s £25m. The pure of heart may be surprised to learn that the price paid by the Government for the site was – yes, the paranoids got it straight away – £21m.

John Prescott himself, who had presided over all this expediency, later owned up to the shambles in a letter of support on the occasion of the establishment of CL:AIRE (Contaminated Land: Applications In Real Environments – a.k.a. the ‘Brownfield Builders’ Club’):

In the past, the answer to cleaning up these sites has been to dispose of the material in landfill sites. This is rarely the most sustainable solution.

He even pointed out the inadequacies of what had been done in Greenwich:

One of the reasons I am supporting the CL:AIRE initiative so strongly is because of our experience at Greenwich. There, because of the time constraints much of the waste material from the site had to be removed and managed off-site.

For ‘managed’ read ‘dumped’ and for ‘off-site’ read ‘in a small village somewhere.’ Clearly, if you’re in a bit of a hurry with your ‘time-constraints’ then anything goes, even spreading nearly a quarter of a million cubic metres of toxic waste around southern England.

Of course, New Labour was never trapped by its history, but only focused on future delivery: that was then, this is now. Some time later Prescott finds it

fitting that one of the legacies of the Greenwich Millennium Experience should be a project aimed at finding long-term, cost effective and practical solutions to the remediation of sites with contamination problems similar to those on the Greenwich Peninsula.

So who will now clean up the Caborn ‘treatment’?

Nobody panic!

I dramatise?

Take down your copy of the Desk Reference Guide to Potentially Contaminative Land Uses by Paul Syms of Sheffield Hallam University – that handy tome!

Look up Appendix 6, ‘Risk Based Classification of Land Uses’. Got it?

Here they all are, homo faber, his devilries, ranked in descending order of hazard from one to 39.

There it is, ranked fourth out of 39, ‘Gasworks, coke works, coal carbonisation and similar sites, Index of Perceived Risk: 8.5, Perceived Risk Category: High.’

As a comparison, one line above, ranked third, you will find: ‘Radioactive materials processing and disposal, 8.8, High’. Example: Sellafield.

No, Greenwich gasworks hasn’t gone away yet – in fact, some of it may be nearer to some of you than you think.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!