Die schöne Müllerin, Chapter 4

Richard Law, UTC 2015-12-03 16:14

The epilogue

We can deal with the epilogue with which Müller closed Die schöne Müllerin quickly: we shall ignore it completely. It says nothing substantive about the poem-cycle. The poet/compère announcing that the lights are about to be put out and wishing the audience goodnight does, however, reinforce the theatre metaphor. It is written in flatulent couplets of fake, ingratiating bonhomie, twenty-six lines that now make us wonder whether our positive feelings about Müller the poet are really justified. Let's conclude by looking at some larger themes.

The problem of the song-cycle

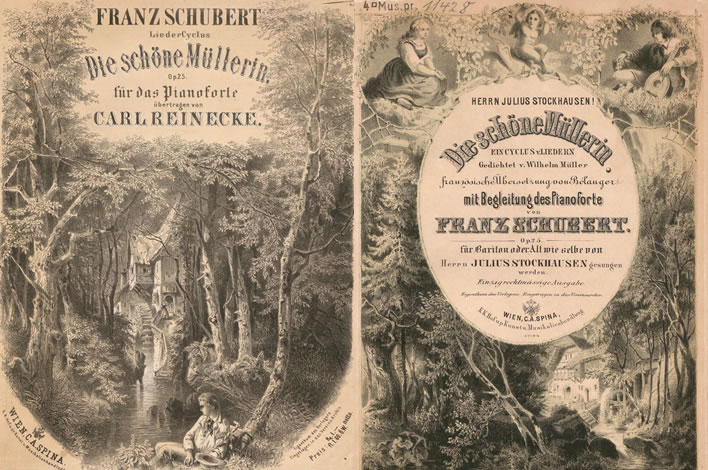

There is no doubt that Schubert was breaking new ground with Die schöne Müllerin, a narrative song-cycle.

If we think about the narrative possibilities of an opera we realise just how many narrative techniques the form offers, a range that includes normal speech, recitative and songs for single and multiple voices. Opera has a physical structure and a structure of acts and scenes that release the spoken and sung words from the duty of scene setting: no one has to sing 'we are now standing in a palace garden'.

A group of songs that are just held together by a single theme – Robert Louis Stevenson's Songs of Travel as set by Ralph Vaughan Williams, for instance – is a series of pieces in which each poem stands alone without narrative. You can perform one of them or eight of them and that in any order, it does not matter.

In contrast, Müller's group for Die schöne Müllerin has to fulfil all the requirements of narrative without any of the techniques and props available to opera. These techniques have, after all, been developed pragmatically over centuries to assist in telling a story in music. Now, in this song-cycle, there are no props, there are simply poems set to music and nothing else. As we have seen in our review of the poems, it is difficult to leave out something without damaging the dramatic development. We can't blame Schubert for this problem – the experiment was clearly worth making and can be counted a great success. However, it is telling that he never attempted to do a narrative song-cycle again. In his other song-cycle, Die Winterreise, there is only the vaguest narrative line. In the putative song-cycle Schwanengesang, which Schubert himself never put together as such, there is even less connection.

If only – our favourite but most pointless phrase – if only Schubert had been able to work together with Müller on the score instead of just having to take over his existing work. The only tool Schubert had available with Müller's text was omission. There are one or two places where Schubert changed words, but these places are rare and trivial. As we have seen in our study of the texts, it was impossible to leave out poems for whatever reason without affecting the narrative integrity of the whole to some extent.

The opera scene in Vienna

Why did Schubert restrict himself in such a way by writing a song-cycle? The answer to this question is embarrassingly simple: because that is the only thing he could do with the means easily available to him.

Writing an opera required expensive and time consuming collaboration with others: librettists and the annoying censors who meddled in their work, orchestras who would not play anything challenging, theatre managements who wanted popular successes and a public whose conservative French and Italianate tastes needed to be educated to the new German forms. Without going into the depressing details, Schubert wore himself out at points trying to produce operas. Rossini was all the rage in Vienna at the time and that was the public taste.

For a song-cycle, in contrast, Schubert needed a large drawing-room, one piano, one pianist (Schubert), one singer and a modest audience. Schubert's entire musical career was devoted to the art of the possible. He wrote so many Lieder because they were things that could be performed easily. He did what he could within the means available to him. Even his chamber music was written because there were plenty of half amateur groups who could perform it. We have no record that Die schöne Müllerin was ever performed in its entirety at a Schubertiade. Individual songs would almost certainly have been performed there from time to time.

The influence of 'that disease' and its treatment

Venereal diseases were a matter of shame then. Pen was rarely put to paper even to acknowledge them, so proving that someone had one of these is rarely simple. The consensus of scholarly opinion is that Schubert picked up syphilis, probably around 1822 and probably in the company of the infamous Franz von Schober, who was also treated for the disease. Schober was a charming reprobate whose entire family had an unsavoury reputation in Viennese society. He and Schubert toured the nightlife of Vienna together.

Let's not be censorious: in the Vienna of the time the space between marital bliss and total chastity was filled by the oldest trade, prostitution. The Emperor Joseph II, ever the rationalist ready to shock, once appalled his deeply pious mother, Empress Maria Theresia, by telling her that there were simpler and cheaper ways of accommodating his deeper drives than marrying some princess or other. When it was suggested to Emperor Franz II/I, on the throne during Schubert's time, that Vienna might benefit from a brothel in order at least to get the trade off the streets he responded that they would 'have to put a roof over the whole of Vienna'.

Ironically, it seems that it was Schober, in fact, who appears to have drawn Schubert's attention to Müller's poetry.

Around 1823 Schubert was blighted by the unpleasant symptoms of early stage syphilis. Unless you were extremely lucky this diagnose was a death sentence, the only question being the number of years you had left and how awful your death from the disease would be. The treatment – we cannot really speak of a cure – was to have the affected parts smeared with mercury ointment or to sit in a high temperature box similar to that of a Turkish bath and expose your body to mercury vapour. Mercury, particular the vapour, is so poisonous that nowadays we would only approach a pot of the mercury ointment of that time in a hazmat suit. Disease and treatment were both death sentences with a slight possibility of a reprieve. Some wag has remarked that at that time you had to be really healthy to survive a course of medical treatment.

It was a testament to Schubert's prodigious powers of concentration and his equally prodigious work-ethic that he managed to keep so productive during his treatment. He hinted at the sickness in a letter to Schober in July 1823. We believe his doctor sent him for treatment to the General Hospital in Vienna, which had its own extensive ward for these problems, in the autumn of 1823. Among other side-effects the mercury caused his hair to fall out and he was forced to wear a wig for some time.

Despite the treatment the symptoms of syphilis dogged him for the remaining years of his life: skin eruptions, bone pains in his left arm, dizzy spells and bouts of depression. In addition he suffered from frequent headaches, which may have been due to his poor eyesight and much scribbling of scores in poor light.

Of course, sexual relations with uninfected women were out of the question. Schubert's later alleged passion for the young Countess Caroline Esterházy was not only hopeless because of the immense difference in their social standing but out of the question because of his illness. Would you let your beautiful, talented and aristocratic daughter marry a syphilitic with no job?

As if this were not enough for one person to put up with there is evidence that his immune system was so depressed by continuous treatment with mercury that when the final, unrelated infection with typhoid fever came in autumn 1828 his body had simply had enough.

The syphilis attack and particularly its treatment came exactly in the time when he was working on Die schöne Müllerin. It seems likely that he was working on the song-cycle even when he was in the hospital. The workaholic also had other theatre projects on the go at this time: Fier(r)abras (D 796), his opera, first performed fifty years after his death in Karlsruhe in 1897 (not even Vienna!) and his incidental music for Rosamunde (D 797), a play performed twice in December 1823 and then withdrawn because of the poor quality of its text, taking Schubert's excellent music down with it.

1823, therefore, was a year of work without profit, of setbacks and rejection, disease, pain and hopelessness. Even though Die schöne Müllerin was published in parts in 1824, Müller, who died in 1827, probably never knew of Schubert's setting that would raise him from obscurity to immortality. The work never received a full scale concert performance until May 1856 in Vienna, Schubert by then dead nearly thirty years. Until then it had never occurred to anyone to sing the twenty songs of the cycle in a single, hour-long performance, showing us just how far ahead of his time our genius was. How on Earth did he keep going?

The lost love

As if we hadn't already piled enough misery on poor Schubert in the course of our attempt to understand Die schöne Müllerin we have to ask, finally, finally, what of Schubert's own 'miller's daughter', Therese Grob?[1]

The Grob family and Schubert's family were close friends. Therese had by all accounts a beautiful singing voice. Her whole family was musical, particularly her brother Heinrich. Franz was frequently in their company.

Schubert told at least one of his friends how much he loved Therese, but, so it seems, never got around to telling her himself. The 'birthday album' we mentioned seems to have been handed to her brother Heinrich, not to her directly.

All Schubert biographers have to come to terms with a depressing fact: only a tiny amount of contemporaneous material about Schubert is known to exist. At his death, Schubert was of concern to only a few people and most of his work was still unpublished. Short obituaries were written and people got on with their lives. As time passed his manuscript scores were recovered bit by bit from dusty old boxes and drawers and Schubert's true greatness began to be appreciated.

Then the biographers got to work. Some started collecting materials and never published them. The few acquaintances who were still living were asked to write down their by now completely befogged recollections of the little Viennese composer, by now long dead. Worse, as Schubert's star ascended, many who barely knew him in life suddenly imagined themselves to be key members of that magical Freundeskreis, that 'Circle of Friends' that became such a staple of Schubert mythology.

In 1865, nearly forty years after Schubert's death, Heinrich Kreissle von Hellborn published the first full biography of the composer. In it the author hinted at Schubert's passion for Therese Grob, which one informant stated was 'violent but which he kept locked within himself'. When the existence of this passion came to the ears of Therese Grob, the girl herself, now a respectable elderly widow, she said that she had never known of any feelings Schubert might have had for her and that the friendship was really just a musical one between Schubert and her brother Heinrich in which she was just a bystander. Her account is believable: at a time when so many were now wanting to associate themselves with the genius, she is the only one distancing herself from him.

Much like our young miller the passion was just in Schubert's mind. He never declared it openly to anyone, how could he? It was a time when the law required a regulated source of income on the part of the bridegroom, and he, the composer scratching along as a teaching assistant, could barely offer that. In 1820 Therese married the master baker Johann Bergmann. Their marriage was a success, his business prospered and at her death in 1875, she, unlike the impoverished composer she never married sixty years before, left a solid estate behind her. If they did not keep in touch we can presume at least that Schubert would have heard news of this old childhood family friend – Vienna was a small large place, after all.

Schubert loved in silence and from afar, his turmoil internal. When he read Müller's poems, particularly those of the second section, how could he fail to think of Therese and her master baker, perhaps even from time to time glimpsed through the windows of the bakery in Wollzeile 29! Our composer is left playing the pipe to amuse the children while the master baker takes his girl.

Coda

Do we know any of this for certain? No, of course not, but our fantasy is harmless, even if it may not be true. Of one thing we can be sure: the stars in von Stägemann's salon in Berlin who were entertained by Müller's yokel verse may have glittered, but it took the dumpy little Austrian composer, Franz Schubert, poor, unknown, rejected, sick and lovelorn to see the potential of Müller's cycle and to create out of it a work of art that continues to blaze long after those Prussian stars have faded.

References

- ^ The account in this section is based on the commendably thorough work of Rita Steblin in Steblin, Rita: 'Schubert’s Beloved Singer Therese Grob: New Documentary Research.' Schubert durch die Brille, vol. 28, 2002, pp. 55-100.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!