Rabid lexicography

Richard Law, UTC 2016-01-26 13:50 Updated on UTC 2016-01-26

Poking the beast

There is much amusement and some salutary lessons to be had from the shakedown of Oxford Dictionaries by a Canadian doctoral student, Michael Oman-Reagan.

The first salutary lesson for any company is that if you staff your social media unit with bright and enthusiastic children on a minimum wage or working as unpaid interns and you reserve your adults for doing important things such as compiling dictionaries then sooner or later your company will come to grief on the social media it is supposed to be managing.

Mr Oman-Reagan, via Twitter, asked OUP,

Why is "rabid feminist" the usage example of "rabid" in your dictionary – maybe change that?

To which one of the rabbits manning the social media unit responded:

If only there were a word to describe how strongly you felt about feminism…

which is touchingly grammatical in barbarous times – 'were'! – and which has a certain look-at-me smarty-pants humour, but which is the equivalent of poking the rabid animal with a stick.

Another twitterat(?) responded to the poke, surprised that a legitimate question was answered with such a dismissive and, frankly, insulting tweet. The offended, outraged and aggrieved don't do humour.

Hello, OUP management! It's Friday afternoon and your admittedly well-educated social media rabbits are about to make you look silly. If the rabid animal you just poked snarls and growls at you, what do you do? Give it another poke, of course. OUP:

Our point is that "rabid" isn’t necessarily a negative adjective, and that example sentence needn't be negative either.

Well, I never. Can this tosh be coming from the same person who used that beautiful 'were'? With the next tweet the embattled rabbits in the OUP bunker hit solid rock with their digging:

Our example sentences come from real-world use and aren't definitions.

Well, of course not, but out of the corpus come thousands of instances of a meaning, from all of which one is selected as exemplary for that meaning. Twitter storm, here we come.

In the meantime Mr Oman-Reagan did some digging in the OUP dictionary for the dog-whistle words that are associated with sexist stereotypes and – who is surprised? – found many. Male doctors and female nurses, female housework and male research etc. The usual suspects.

After a weekend of being savaged by the rabid animals on social media it was time for the adults at OUP to enter the social media bunker and drag the clever kids away from their computers. Soothing assurances were issued, the situation would be reviewed, very sorry etc. According to The Guardian:

In a statement on Monday, a spokesperson for OUP added that the Twitter comments had been “ill-judged”.

“We apologise for the offence that these comments caused,” said the statement. “The example sentences we use are taken from a huge variety of different sources and do not represent the views or opinions of Oxford University Press. That said, we are now reviewing the example sentence for ‘rabid’ to ensure that it reflects current usage.”

The OUP spokesperson added that the publisher reviews “all of our example sentences to ensure they reflect current usage on an ongoing basis”, and would also be reviewing the other examples raised by Oman-Reagan.

The shakedown was complete.

Harmless drudgery

The second exemplary lesson is 'think about the problem before you cave in and apologise'.

Ah, those blissful times when a lexicographer was just 'a harmless drudge' (Samuel Johnson, definition of 'lexicographer'). The great Oxford English Dictionary was based 'on historical principles' it told us in the title. The examples for entries were collected from known sources by many volunteers.[1] Extremely learned scholars sorted and defined. (Just try it yourself: write the entry for 'put'.) In the OED the examples for each entry were given with references to their source.

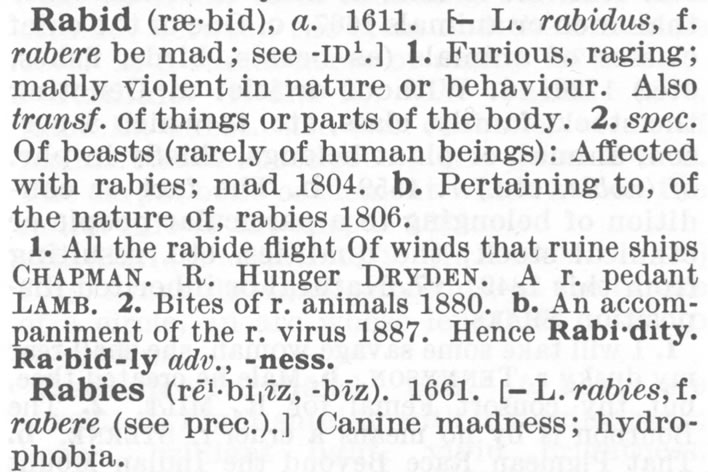

Next to me within handy reach is the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary from 1980 – Oh those innocent times! Here is what it says about 'rabid':

Now, of course, 'rabid' is never going to be a neutral word or a word of praise, contrary to the current opinion of the clever kids in the social media bunker at OUP. Its root meaning 'mad' was applied to an animal crazed by the disease rabies. It was a good word of invective for use against whatever or whoevever was unpredictably wild, raving and dangerous. I like the example from Charles Lamb, 'a rabid pedant'. No one likes a pedant, especially not on this blog, so everyone can get behind that example. Using a 'rabid Whig' or a 'rabid Tory' would have been thought unacceptable even in the earliest days of the OED.

Such sensitivities were always part of the lexicographer's intellectual equipment. We can therefore completely agree with Mr Oman-Reagan that, if OUP is going to insult someone or something in the example sentences it had better watch out. The trouble with this high and mighty judgement is that the best examples – the most comprehensible and exemplary ones – are quite specific. They need that specificity to illuminate the dry definition.

OUP told Mr Oman-Reagan that the highest frequency example in the corpus is 'rabid fan', followed somewhere by 'rabid supporter'. From a lexicographer's view, these two examples are much inferior to 'rabid feminist'. We all know what one of those is, whereas I am not at all sure what a 'rabid fan' is. I'm not too sure how a 'fan' can be thought to be rabid, but that's another debate. A 'rabid supporter' is an endearing and confusing conjunction of the viciously fanatical and the helpful: in fact, a really terrible and incomprehensible example. If OUP were to use either of these two as their example their lexicographical future will be bleak.

_ByJamesGillray_1783_708x575.jpg)

Dr Johnson being pursued by an enraged Twitter mob of rabid feminists.

Samuel Johnson ('Apollo and the muses, inflicting penance on Dr Pomposo, round Parnassus') by James Gillray, 1783. National Portrait Gallery, London.

Since the advent of computing, lexicographers have moved from using literary sources of language and the occasional newspaper of record to using databases, which gobble up language from all sources: tabloids, magazines, blogs, government reports etc. Now democritised, they scrape up not only immense amounts of usage, but also much defective usage. I haven't looked into OUP's corpus for 'rabid', but I'm pretty sure that, as we have seen with the higher scoring examples, a lot of the entries will be confused rubbish.

Rewriting the past, shaping the future

Unfortunately, Mr Oman-Reagan is trying to sneak another principle altogether through the fog of Twitter battle. According to him, dictionaries, because they are used by moderns as a look-up device, have to offer only definitions and explanations that are in tune with the current, right-on, intellectual climate. They have to set whatever the right-on language agenda of the time is. The dictionary can therefore no longer be on 'historical principles'. Even if the occurrences of 'housework' in the Oxford corpus are massively female-related, the example will have to be tweaked to suit present and future sensibilities.

Various linguistic ruptures have taken place as a result of the 'issue-battles' of recent decades: French Marxist philosophers have emphasised the role of language in reflecting and shaping society; the sociologists of this and that, the linguistic anthropologists and even the 'anthropologists of space, science and social movements' such as Mr Oman-Reagan have done their bit to make the common tongue a minefield of 'issues' and deeper, almost Freudian meanings. As a result, the past is not just a 'foreign country', it is a country with borders and guards, it is a country one cannot enter without a special permit and about which one can no longer carry report without scrutiny, because one of these usages might just pop up and frighten you. I'm not even sure we can talk about history anymore, so filtered it has to be through the tastes and sensibilities of the present.

Even our dictionaries are going to be sanitised in the search for political and social correctness. OUP, the big one, has already buckled. Who's the next shakedown victim going to be?

Update 26.01.2016

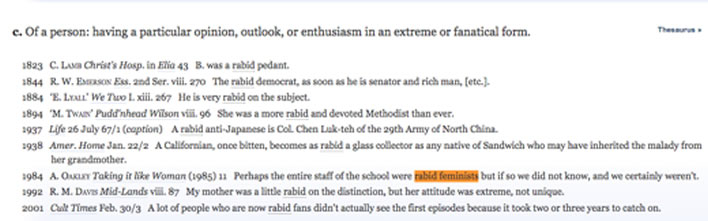

Brendan O'Neill does the legwork I didn't and finds the full citation in, I presume, the full OED:

Perhaps the entire staff of the school were rabid feminists but if so we did not know, and certainly we weren't.

A quote dated 1984, taken from Taking it like Woman[2], a book by the noted feminist writer and sociologist Ann Oakley.[3]In the OED there are nine examples given for the word 'rabid' applied to a person. Most of them for my taste are lacking in the specificity we already discussed: sometimes more really does mean less.

In the OUP online dictionary example for 'rabid' there is initially only one example, in which the phrase is shortened to just 'a rabid feminist' without any attribution. On demand there are three further examples, none of which is attributed or contained in O'Neill's full OED list.

All the more reason for OUP not to cave in so quickly.

References

- ^ An interesting and well-written story relating to the creation of the great OED is to be found in Simon Winchester, The Surgeon of Crowthorne, Viking, London, 1998.

- ^ The OED list is inaccurate. The correct title of the book is Taking it Like a Woman, Flamingo, London, 1985.

- ^ Anne Oakley the feminist not only supplied the contested quote about 'rabid feminists', has also written a number of best-selling and respected books on the contested 'housework' theme such as The Housewife (1974), The sociology of housework (1974) and Woman's work: the housewife, past and present (1976).

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!