Christian Schubart – Taking the bait

Richard Law, UTC 2016-02-07 16:54

Ulm, the last stop on the journey

Schubart arrived in Ulm in January 1775. He was 35 years old.

In the preceding two years he had been imprisoned for adultery, excommunicated, thrown out of his job and thrown out of Württemberg; he had abandoned his wife and family and had wandered around southern Germany, living on his wits and talent as a musical performer. He had almost converted to Catholicism in Munich and had been finally thrown out of Bavaria; he had made lasting enemies of the Catholics and especially the Jesuits in Augsburg, had been thrown out of that city and it was only through a lucky escape that he made it to Ulm in one piece.

At first, life in Ulm went well for Schubart. He quickly found an apartment. The German Chronicle he had started the year before was going from strength to strength: it was earning around 30 gulden a month for him. He was soon busy giving concerts and music lessons as well as writing poems and texts for weddings and funerals, most of which were well paid.

The family reunion

There was serious unfinished business, however. Only a month or so after arriving in Ulm he went to Geislingen and saw his wife for the first time in nearly two years. Schubart wrote an account of the reunion with his family.

I entered the melancholy room, where she was sitting at the sewing table, looking ill and thinking only of my wellbeing. When she saw me she stood up, stretched her arms out towards me in silence, white as a corpse. 'Here's your wanderer!' I said and threw myself into the chair. 'Oh it's good just to have you back!' she replied tenderly and lovingly. She cried and I sat like a stick that is hardened against thunder and rain. 'Do you want to come with me? tell me – I'm in Ulm now. The storm has driven me out of Augsburg. What I have is yours!' 'Oh yes, I want to come with you and only death shall separate us again.' She brought my children in: 'Now you don't need to talk to your father's portrait: he's here himself.' [SLG II. p. 70.]

Helene had lived through a nightmare in the previous year. It is a nightmare which we should not overlook, distracted though we may have been by Schubart's colourful wanderings. On top of chronic ill health, she had had to endure the shame of her husband's public adultery with a maid; she had been abandoned with their children in Ludwigsburg, without even a goodbye; already weakened, she had herself contracted typhus during the care of her mother and brother, who were both dying from the disease. For most of that terrible time she had no idea where her husband was, whether he was alive or dead and whether she would ever see him again.

Astonishingly, given all that had happened in the meantime, even Schubart and Bühler, his father-in-law, were reconciled during his stay in Geislingen. In all Schubart's accounts of his dealings with Bühler, despite the vicious hostility of some of Bühler's actions against him in Geislingen, Schubart's tone is almost always mild and conciliatory, acknowledging freely – often too freely – his own defects and shortcomings. He clearly never bore a grudge against Bühler and was open to the reconciliation when it came.

The happiness was therefore seemingly complete when Schubart returned with his family to Ulm. Even Helene's health, which had been in a more or less poor state since Ludwigsburg, began to improve now those dark years were behind her. Ludwig left the constraints of the provincial school in Geislingen and was now sent to the Gymnasium in Ulm. He was also starting to show musical talent.

Life in Ulm

In Ulm Schubart was now also in direct, daily contact with friends and supporters, not just sponsors. They were able to take the edge off some of his native wildness and their presence probably also gave him a feeling of security, at least for a while. His most constant companions, though, were beer, wine and tobacco. By his own admission he was one who 'ate little and therefore drank more'. There are reports of the regular consumption of heroic amounts of wine, but these are not very reliable. Schubart himself identified alcoholism as one of his failures and suggests that his excesses, particularly. those when he had a visitor to entertain, damaged his health (he was 52 when he died). Such statements may have been his own exaggerations, made in his autobiography whilst he was beating his breast in remorse for all his peccadilloes.

Despite his consumption of alcohol he was as productive in Ulm as never before, writing, virtually single-handedly, his German Chronicle twice a week as well as giving music lessons and writing articles for other journals.

Apart from wine, another Bacchanalian element in Schubart's life was women. His family life may have become whole again in Ulm, but his 'love for the fair sex' continued unabated. He is discreet and so we only have occasional hints from his letters that his life in Ulm was not monastic. In April 1775, he reported on his condition to his brother:

Today is my birthday! I, old fool, am now 36 years old! and still have an appetite for eating, drinking and sex.

However, after only a month or two of recovery in Ulm, Helene's health declined. Schubart just did not have the temperament for caring for someone who was chronically ill:

She is neither living nor dead. It's just such a continual brooding, sighing, complaining and crying that it is a misery to have to stand by and watch it.

He also remarks in a letter to his brother in mid-June 1775 that he has only one male successor and so it will remain, for 'there is nothing more to be done' with his very ill wife.

The journalist arises

His German Chronicle was now the thread that ran through his life and held it all together. It earned him money and brought him recognition and even modest fame. It must have given Schubart particular pleasure that his father, at the end of his life, was spreading the word around Aalen about his son's German Chronicle and even bringing in subscriptions.

Writing the German Chronicle – or rather, dictating it – was a pleasurable duty that gave his life some order, a duty he could perform in the tavern with a tankard of beer and a pipeful of tobacco. Nothing he had done in the past had offered all these things at once. But most of all, through the German Chronicle he was able to give his German patriotism and satirical spirit full rein. He was now doing something in which he really believed and not just delivering a moment's distraction for princes and courtiers.

As a chronicler of his times, Schubart in Ulm was the right man in the right place. His experiences – good, bad and terrible – in many different fragments of the German patchwork had given him not just a deep fund of anecdotes but also a deep fund of insights into the condition of the German-speaking world at the end of the eighteenth century. His past, with all its errors and wanderings, was no longer a wasted time, full of failures, regrets and missed opportunities, but a valuable resource. Without that resource he could not be what he now was in Ulm, the author of the German Chronicle.

Schubart was in his heart a journalist: most of his work is scattered in fragments throughout ephemeral flysheets, newspapers and magazines. Solid products that got into libraries and survived the passing of the years were few and far between.

Schubart's experience and personality made him into a ground-breaking journalist and commentator, his success demonstrated in the growing sales of the German Chronicle. For Schubart's contemporaries, reading the German Chronicle was like listening to the conversation of an amusing and talented companion in the tavern – for that, in effect, is what it was. Its risky wit made it an interesting read: well written, provocative opinion and satire that promoted discussion and controversy. That same controversy was dangerous, however.

It is easy for us now to say that Schubart was incautious, that he should have been more circumspect, more diplomatic. The German Chronicle would have been the duller for it. It would have been just like all the other publications of the time and Schubart, just like nearly all the other writers of the ephemera of the time, would have faded from our view.

For all the many character defects we have found in Christian Schubart and the many ways in which we have found him wanting, we have to acknowledge that he was either a very brave or a very foolhardy man. Perhaps his impetuosity and refusal to think of the consequences of his actions, the kind of impetuosity demonstrated by his immediate departure from Ludwigsburg, was the anaesthetic to the fear a shrewder or more prudent person would feel. Impetuosity, imprudence, call it what one will, now led Schubart to the final step to his doom.

The art of making enemies

In Schubart's life so far there is one talent that stands out above all others: his talent for making enemies. Whether they were university authorities, school supervisors, Protestant clerics, Catholic friars, even his own in-laws, Schubart annoyed them with masterful ease. Schubart had been assiduously making enemies of the great and the good: insulting them to their faces; insulting them in the tavern behind their backs, his loud voice booming out to everyone in the room; insulting them in print, both prose and verse, then distributing these insults around Germany and even Europe. He had fairly even-handedly mocked Catholics and Protestants of every flavour, as well as a large number of people with title or position.

Now, in Ulm, he had his German Chronicle with a growing circulation throughout Europe – now he could really annoy people.

Annoying the Catholics

Despite having been driven out of Augsburg in fear of his life by the Catholic faction there he kept his anti-Catholic campaign going with renewed fervour from the apparent safety of Ulm. He bitterly attacked the faith healer and exorcist Johann Gassner, who had what we can only describe as an exorcism roadshow touring South Germany at the time.

Not content with attacking Gassner and his powerful supporters Schubart also turned his critical attention to the famous 'Disputation Preacher', Alois Merz. Merz was a Jesuit priest who was the preacher at the cathedral of Augsburg. He was one of the most prolific and quick-witted of a group of polemical Catholic preachers at the time who argued the case for strict Catholic dogma against both Protestants and even also 'soft' Catholics.

Protestant preachers, in contrast, avoided doctrinal disputes with Catholics, largely confining themselves instead to personal aspects of theology such a repentance and salvation. Into this vacuum leapt Schubart. He was left more or less alone to fight the Protestant cause in the face of the new Catholic assertiveness. His friends and supporters – wisely for them – stayed silent.

The case of Josef Nickel, a young man whom Schubart had got to know in Ulm, affected and frightened Schubart deeply. Nickel had fallen foul of the Capuchin monks of nearby Wiblingen Abbey, having expressed his anti-clerical opinions too freely in public. He was condemned to death by burning and put to death at eight in the morning on 1st June 1776, on a piece of raised ground next to the river Iller and in front of a large crowd of spectators. His head was hacked off first as a merciful gesture, his remains burned on a pyre and the ashes thrown in the river.

Schubart was deeply shocked at Nickel's fate, even more so when some began to say, according to Schubart, that it was the young man's association with him and even the book that Schubart had lent him that was the cause of his downfall. Schubart must have now realised, if he had not done already, how close his escape had been when he ran into the enraged priests in the post inn in Günzburg.

It is an astonishing reflection of the conditions in Germany at the time that while Josef Nickel was being hacked to death and burnt in Wiblingen, seven kilometres away in Ulm Schubart was living relatively securely in an Imperial city that tolerated – up to a point – free expression and debate. The Peace of Westphalia that ended the Thirty Years War left a patchwork of nearly 300 fragment states in Germany, each of which had a great deal of autonomy, particularly in judicial matters. These fragments ranged from major states such as Prussia, through kingdoms, principalities, dukedoms, imperial cities and down to many tiny areas under the control of a particular body such as an Abbey. The Abbey of Wiblingen is a good example of this: once Nickel was within its territory, it could do what it wanted with him. And it did. For the moment though, Schubart was safe in Ulm.

Annoying the Austrian Empire

These many Catholic enemies were bad enough, but his two most serious enemies were political and extremely powerful: the Austrian Empire in the person of General von Ried, its representative in Ulm, and Carl Eugen, Duke of Württemberg.

Schubart had already annoyed General von Ried:

The Imperial Minister in Ulm, General Ried, a proud, imperious man, was extremely annoyed, because I was supposed to play the piano for him and refused to do it because the piano was unsuitable. [SLG II. p. 130.]

General Joseph Heinrich Freiherr von Ried was a Catholic, and according to Schubart, fellow Catholics fanned the flames of this fire with von Ried. After the insult, von Ried just bided his time, waiting for a better reason to come along so that he could seize Schubart. The better reason came shortly afterwards, when Schubart published the following in the German Chronicle for 6 January 1777:

[Emperor] Joseph [of Austria], who, like the gods of the Golden Age, without ostentation and recognized solely by the deeds of the heart, wanted to tour part of Germany and the most important provinces of France … is now, we are informed, unable to make this journey as a result of the sudden illness of his mother. Reliable reports from Vienna contain the sad news that the great Empress, in the middle of the appearance of the most permanent health has suffered a stroke. Let us hope that I can withdraw this news in the next issue!

The modern reader will probably need some help to appreciate the mockery behind these insults. Joseph II was renowned for the many journeys he made to the distant corners of his empire, always travelling incognito under the alias of 'Count von Falkenstein'. This subterfuge supposedly allowed him to see things as they really were and not as they would be shown to an emperor. Of course, everyone knew who 'Count von Falkenstein' was and the incognito was just characteristic virtue signalling by a ruler who claimed to care nothing for common approval but who, in fact, went out of his way to cultivate it. If they didn't already know, Schubart had told his German Chronicle readers only a few weeks before (26 December 1776):

On the 8 January, using the name Count von Falkenstein, he [the Emperor Joseph] will arrive in Munich, where preparations are already being made for the worthy reception of such a guest. … What a feeling of joy would raise us up as though on wings if Joseph – the worthy son of the great Theresia, the German empress, appeared [in Ulm]! Oh that we are not deceived in our sweet hopes!— The more the Emperor in Paris forbade all ceremony, the grander and more festive were the celebrations for his reception.

Having mocked his alias and drizzled sycophantic goo over him in December, the description in January of Joseph, impudently named without his title, 'like the gods of the Golden Age' is the finest persiflage from a master of the genre. Suggesting that the Emperor Joseph II would be travelling around Europe without pomp and would only be recognized by the goodness of his heart is satire of the highest order, satire over which the subscribers to the German Chronicle throughout Europe would be chuckling.

This venomous mockery is then used to introduce a cheeky speculation on the health of the great Empress Maria Theresia, a passage that in itself was extremely provocative. At the time Maria Theresia and Joseph were co-regents of the Austrian Empire. When she died, Joseph, the incognito traveller, would become sole ruler.

The Austrian Empire was deeply Catholic, and von Ried would have known with distaste of Schubart's Protestant background and his attacks on the Catholic church. Maria Theresia was piously Catholic, whereas her son Joseph allegedly took a more flexible approach. Even without the satirical introduction, a Protestant publishing untrue reports of her ill-health in this context was extremely offensive.

When Schubart made an enemy, he really made one. Not only did he personally insult von Ried and mock his Emperors, of all the people he held up for praise it was the Prussians and their King, Frederick the Great, whom he had admired all his life. Prussia was the arch enemy of Austria and von Ried himself had played a role in the infamous Hussar Raid on Berlin during the Seven Years War (1756-1763). Von Ried was no friend of Prussians and Protestants and so Schubart, once he was on von Ried's little list as a propagandist for both of them, would clearly not be missed.

Annoying Carl Eugen, Duke of Württemberg

According to Schubart, General von Ried told Duke Carl Eugen of his decision to carry him off to rot forever out of sight in one of the distant and dreaded Hungarian prisons located within the Austrian Empire. In reply, Carl Eugen promised von Ried that he would deal with Schubart himself, since he, too, had 'not a few reasons' to want him silenced. For the Duke, this was going to be a very personal solution.

In his German Chronicle Schubart had attacked Carl Eugen on a number of occasions, particularly for recruiting (i.e. kidnapping) men by force from Württemberg then hiring them out to fight and die on behalf of foreigners in foreign wars for the Duke's personal enrichment. The Duke's spirited imitations of the excesses of the French court meant that he was permanently short of money. For Carl Eugen, once Schubart, his former Organist and Music Director, started the German Chronicle and began spreading his criticisms around the entire German-speaking world and beyond, he was a marked man.

But much more dangerous than that, there was also a deep personal hatred between Schubart and Duke Carl Eugen. It seems to date from Schubart's time at Carl Eugen's court in Ludwigsburg and not only involved the Duke but his mistress, later his wife, Franziska von Leutrum (later von Hohenheim).

In Ludwigsburg she had received piano lessons from Schubart. Whether during the course of these he had tried to seduce her, as he had so many of his pupils, we can only speculate. It would have been a characteristically Schubartian piece of hubris and dangerous recklessness. Did he try it? Was he rebuffed? Was he accepted? Did he enjoy forcing the jealous Duke to sit in on those lessons as a chaperone, as he would later stoke the Duke's jealousy with a poem that hinted at the seduction of Franziska by his court painter?

His Serene Radiance Carl Eugen, Duke of Württemberg (1728-1793), painted in Rome in 1753 by Pompeo Batoni.

In this comedy of manners we have Carl Eugen, the serial adulterer, who did his bit to populate Württemberg with illegitimate offspring with just about any young woman who took his fancy, Schubart, the other serial adulterer and Franziska the mistress and marriage wrecker. In comparison, the goings-on in Beaumarchais' play of the time, La Folle Journée ou le Mariage de Figaro (1778, Mozart/da Ponte opera, 1786) seem restrained. In Augsburg in 1774 Schubart had even tried to stoke up the Duke's jealousy using a poem in the German Chronicle. In a letter written in 1775 Schubart was venomously insulting to the pair, but particularly to Franziska.

Whatever the reasons – Carl Eugen's hatred, Franziska's hatred, von Ried's hatred, the Catholics' hatred – any one or any combination of them, Schubart's doom arrived in January 1777.

Carl Eugen strikes

Doom took the form of a order issued in the name of Duke Carl Eugen dated 18 January 1777. (We remember that Schubart's mocking piece about Emperor Joseph II and Maria Theresia had appeared in the German Chronicle barely two weeks before that). The order was sent to the Administrator of Blaubeuren Abbey, Philipp Friedrich Scholl. The abbey was Protestant and firmly on Württemberg soil, even though it was only a little over 15 kilometres from Ulm. The order[1] first regurgitates the complaints that had been raised against Schubart during his dark three years at the court in Ludwigsburg.

[You] will not be unaware that a few years ago the then City Organist in Ludwigsburg, Schubart, partly because of his reprehensible and irritating behaviour, partly because of his very wicked and even blasphemous writings was, at the most respectful request of the Ducal Privy Council and Consistory, removed from his post and expelled. Next, the order summarises Schubart's present occupation as the writer and publisher of the infamous German Chronicle. It is well known that this man, who now lives in Ulm, continues in this fashion and is now so brazen that there is no crowned head or prince on earth who has not been affected in the most disrespectful way. For this reason His Serene Ducal Radiance decided some time ago to seize him and hold him in safe custody in order to cleanse human society of this unworthy and contagious member.

The order then explicitly rules out the use of the normal legal remedies.

An application to the Magistrate in Ulm is regarded by his Radiance as too circuitous and might even subvert the achievement of our goal, which could be best achieved if Schubart, under some pretext that took account of his habits and his passions, were to be lured onto incontestable Württemberg territory, at which moment he could be immediately taken and imprisoned.

We need to remember at this point that Schubart was not a citizen of Ulm or Württemberg or, in fact, anywhere. Soon after he was born in Obersontheim in the independent county of Limpurg, his family moved to Aalen, an independent imperial city, where he spent his childhood and youth. Neither in Aalen nor in any of the places on his subsequent wanderings did he acquire citizenship, which would at least have given him some legal status.

Had Carl Eugen followed the legal route, once the request for Schubart's arrest had been sent to the Magistrate in Ulm, secrecy could no longer be maintained and his supporters and protectors could have spirited him away before an arrest could have been effected.

Avoiding judicial process also brought with it the extremely important advantage for Carl Eugen that no charges had to be specified, no evidence need be supplied and no defence was possible.

The order also contains the outline for the execution of the plan, which reveals that this is no hasty, last minute act of anger. The members of a careful conspiracy are designated and the detailed planning left to them to work out in only oral discussions.

For this purpose His Ducal Radiance is sending Major von Varenbühler to Blaubeuren in order to consult with the Chamberlain and Chief Forester, Count von Sponeck, with the Town Clerk, Georgii, and with the Administrator of Blaubeuren Abbey, Scholl, all of whom will discuss the matter and choose the most appropriate means, which will then be effected according to an agreed plan in a way that will fulfil the requirements set by his Radiance. Major von Varenbühler has already received the necessary arrest order.

Major Varenbühler was one of the five Flugel-Adjutanten at Carl Eugen's court. A Flugel-Adjutant was a military officer personally assigned to the Duke. This fact meant that he could be sent off on the Duke's mission to arrest Schubart without needing to invoke a line of command, which would be the case for a normal military position. In the normal case, Carl Eugen would give a command to a general and this command would then filter down to the appropriate officer. As a Flugel-Adjutant, Varenbühler stood outside the established line of military command and could be sent off to do Carl Eugen's bidding without further ado – essential in the arrest of Schubart in order to preserve secrecy.

Schubart the poacher

What was the Chief Forester, Count von Sponeck, doing in this group? Count Friedrich Ludwig von Sponeck was a Chamberlain to the Duke and therefore part of his inner circle. He was the Dukes' eyes and ears in the case. He was Chief Forester of the Forestry Department of Schorndorf.

The management of forests as we would understand it nowadays was only a small part of his activity. His staff of gamekeepers were organized on military lines and their principal task was the prevention of poaching, which was considered to be a grave crime and was punished accordingly by hanging, hard labour or lifelong imprisonment. Wanted poachers could even have a price put on their heads and could be taken dead or alive.

Powers of arrest and summary imprisonment were extended to other crimes besides poaching. The legal procedure for the arrest and punishment of a poacher or other miscreant required the presence of both the Chief Forester and at least one senior administrator such as a Town Clerk, who would preside over the interrogation and send a report to the ducal administration. In this case that role would be fulfilled by the presence of Georgii in the group. It is striking that, except for the presence of Major von Varenbühler, the structure of the arresting group for Schubart therefore fitted the standard format for the arrest and interrogation of a poacher or other common criminal.

Scholl in the vice

Let us return to the decree: Scholl is now forcefully reminded of his duty to his ruler and the need for absolute secrecy.

The successful execution of this plan is almost entirely dependent on maintaining the strictest secrecy. If the Administrator of Blaubeuren Abbey, Scholl, wishes to enjoy the continued benefit and protection of His Serene Ducal Radiance – that can only be so greatly in his own interest – he should observe the most inviolable secrecy with everyone and proceed cleverly and forcefully in accordance with his responsibilities.

What must Scholl have thought when he received this order! 'Can only be so greatly in his own interest'! He had bought his post from Carl Eugen for 1,000 gulden five years before, handing the money over to the Duke in person. The forty year old lawyer, a professional administrator, a grey mouse quietly running a provincial abbey, his hobby mapping Roman roads, a man with a wife and eleven – repeat, eleven – children to maintain, is suddenly required to participate in a secret conspiracy to trick the famous writer Schubart into prison. There was no reasonable possibility of refusal. Failure would also have brought consequences. Success would also bring consequences for Scholl, who, for Schubart's many supporters, would become the Judas in the poet's martyrdom. Procrastination over the Duke's direct order was also not an option. The plan went into effect almost immediately.[2]

Scholl casts the bait

In Ulm on Wednesday, 22 January 1777, sometime during the morning, Schubart received a visitor, the Administrator of Blaubeuren Abbey, Philipp Scholl. We can assume that Schubart had already got to know Scholl, possibly from his Ludwigsburg years, or more recently in Ulm – Scholl's job at the abbey would require him on occasion to go to Ulm.

Scholl invited Schubart to lunch at the hostel Zum Baumstark in the Glöcklergasse in the centre of Ulm. Schubart was a regular at the Baumstark, he also gave concerts there and organized other events, particularly during the carnival period in February. It was in places such as the Baumstark that he dictated his German Chronicle. For the gregarious and convivial Schubart, being taken out to lunch with someone else paying was probably always welcome, so, despite having to give a music lesson later and a concert performance that evening he accepted Scholl's invitation.

On the way to the Baumstark, Scholl asked him – 'very timidly' – whether Schubart would do him a very great favour. His brother-in-law 'Professor B****r von E****g' was staying with Scholl in Blaubeuren and would like to get to know him: would he go with him to Blaubeuren the following day, Thursday? Schubart tells us that he had two reasons not to accept the invitation: the professor had already met him in Stuttgart and he had to write his German Chronicle tomorrow. Despite this, he would go – and get his Chronicle written on time, too!

The irresistable bait

In is autobiography the name 'Professor B****r von E****g' was obscured by Schubart to protect the identity of a person for whom he had great respect and who was not in any way associated with Carl Eugen's trap. It was Schubart's great respect for this person that was the bait on the hook which caught him. Whether the final 'g' in 'E****g' is just a slip of the pen or a further attempt to disguise the name so that only those already in the know would recognize it is uncertain.

That person was Johann Friedrich Breyer, Scholl's brother-in-law, became Professor of Logic and Metaphysics at the University of Erlangen (at that time part of Prussia) in 1770. In that year he was also present at the baptism of the child that would become the great Hegel. The chair he obtained at Erlangen was no minor post. It had been created the year before specially for the other great German philosopher, Emmanuel Kant. In the end, Kant, in permanently frail health and lacking any real desire to leave his beloved Königsberg, declined the post. It was offered to Breyer, then at the University of Tübingen. That he was the preferred choice to take the chair created for the great Kant indicates how respected he had already become.

Schubart would certainly not want to pass up the opportunity to meet such a cultured and civilised man, especially when he had (according to Scholl) specifically requested a meeting with Schubart. It is usual to assume that it was vanity and a craving for recognition on Schubart's part that caused him to rush off to meet 'Professor B****r von E****g' despite all his misgivings.

But now that we know that Scholl really did have Professor Breyer as a brother-in-law and we can imagine what Professor Breyer would mean to Schubart, we can appreciate just how good Scholl's deception was – brilliant, in fact. It had a core of truth to it and fitted in with what Schubart probably already knew of the illustrious Breyer. There were plenty of reasons that Schubart would have for taking the opportunity to meet an outstanding man with interests in philosophy, culture and language, even though the timing was not totally convenient. The bait was crafted perfectly to be attractive to the prey.

The trout takes the bait

The following morning Schubart got up and prepared himself for the journey. His children said nothing, Helene trembled. The sleigh arrived at their apartment and Schubart said farewell to his family. Helene, pale and trembling, said 'Can't this stranger come to you?', the last words he was to hear from her for nine years. His son had taken an immediate dislike to Scholl – as Schubart put it, 'his bailiff's face as repellent to him as worm-seed' (the bitter seeds of one of the wormwoods, absinthe santonicum, given to children to purge them of intestinal worms).

Despite the sense of foreboding that hung over the whole project Schubart went with Scholl. Why did he take the bait?

As we have seen, the bait in itself was a very tempting one, but we have the impression that Schubart was more worried by the many Catholic religious fanatics who were clearly out to get him. Württemberg was Protestant, solidly Pietist at that, and there he would be safe from his Catholic enemies. He underestimated the bitter emnity of Carl Eugen and Franziska and knew nothing at that time about General von Ried's intervention. What could go wrong?

As the sleigh set off Ludwig shouted from the window 'Papa, come back soon!' The sleigh took him to the Baumstark to collect Scholl, then they set off on the journey over the snowy fields to Blaubeuren [SLG II. p. 135.].

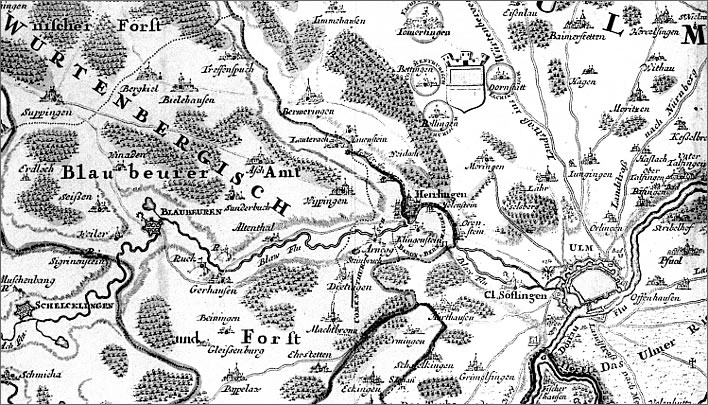

Map of Ulm and Blaubeuren, 1720 (private collection).

Most of the journey passed in silence.

My guide, absorbed in his black plans and possibly already calculating the advantage that a catch of this type would have for him, spoke little. I, normally such a talkative pilgrim, sat there like a statue. [SLG II. p. 138.]

The sleigh pulled into the courtyard of the Abbey around mid-morning. Scholl escorted Schubart to the administration building. Just inside the front door he was ushered into the office on the right.

The entry into the room promised nothing good; no one was there to welcome me, everything was so silent, just like a mortuary. Even my guide had abandoned me and I was left alone with with a girl sitting sadly at a spinning wheel, who looked at me sadly every time the spindle fell to the floor.

And suddenly the door opened. Major von Varenbühler entered, followed by Count von Sponeck, then after him the Town Clerk of Blaubeuren and then my guide, Scholl. Varenbühler announced my arrest on the orders of His Serene Radiance the Duke. I thought it was a joke, since I had known Varenbühler from Ludwigsburg, but his concerned expression and some further words convinced me of the full seriousness of his task.

The Major's face displayed his unfeigned sympathy. Scholl, however, went backwards and forwards with his wife, whimpering 'I'm so sorry! God knows, I'm so sorry!' The girl at the spinning wheel jumped up and buried her weeping face in her apron. Count von Sponeck remained cold – as Head Forester, catching a prey was nothing new to him. The face of the Blaubeuren Town Clerk Georgii [Schubart mistakenly calls him 'Oetinger'] was full of sympathy and comfort. He shook my hand in a brotherly way, spoke to me encouragingly and gave me his gloves for the journey, his eyes welling up with tears. [SLG II. p. 138f.]

Schubart's arrest in Blaubeuren. Frontispiece from Schubart's Leben und Gesinnung, 2. Theil, Stuttgart, 1793.

The arrest was a complete surprise for Schubart, showing us just how good Scholl's deception had been: 'I thought it was a joke' was his first reaction. How unexpected the arrest was is also shown by Schubart's shocked state afterwards.

I was allowed to write to my wife, but my hand seemed paralysed. I ate nothing for lunch and climbed into the carriage like a criminal surrounded by a gawking rabble. [SLG II. p. 140.]

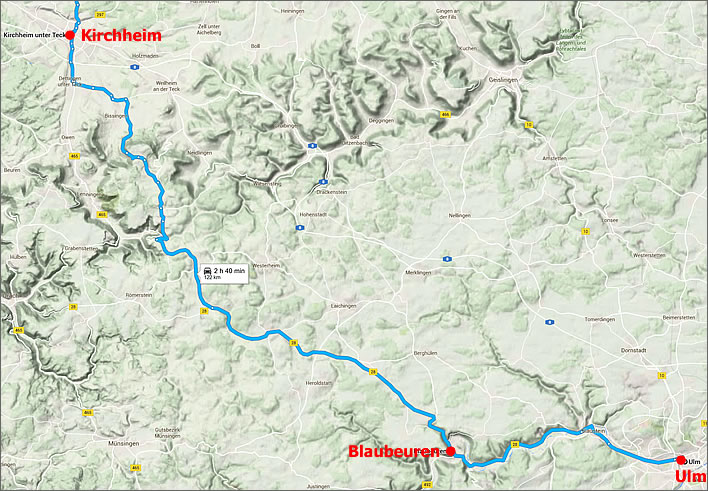

Approximate route from Ulm to Blaubeuren and from thence to Kirchheim on the first day of Schubart's journey to imprisonment in Hohenasperg. If only the escort had had Google the travellers could have completed the journey in 2 hours and 40 minutes, instead of two days.

Major von Varenbühler sat next to him in the carriage. Schubart began to worry about the future of his wife and children: he had left scarcely enough money for them to survive a few days. The Major promised him he would speak to the Duke on their behalf.

By the evening they had covered about 45 kilometres on wintry roads. Of the journey, Schubart notes only that he chain-smoked his pipe. They stayed overnight at Kirchheim. He was not cheered to overhear the two guards on his room talking about him.

That's Schubart! the condemned fella! He's going to get his head hacked off. [SLG II. p. 141.]

He barely slept a wink after that. Varenbühler had sent an express messenger to the Duke for further orders. According to Schubart, the Duke had initially decided to send him to the fortress of Hohentwiel, which would have conjured up images in his mind of all the people who had been executed there or those who, such as the infamous Colonel Rieger, had endured years of mistreatment and misery. The fact that Varenbühler had needed to request further orders for the final destination indicates, however, that Carl Eugen had not made up his mind about what to do with his catch. Schubart was relieved when a rider returned with the message: Hohenasperg!

Day 2 of Schubart's journey to Hohenasperg. Overnight at Kirchheim, lunch at Cannstatt and then imprisonment in the fortress. Carl Eugen's two main residences were at Ludwigsburg and Stuttgart. There was no clearly defined capital or Württemberg at the time – the capital was wherever his Radiance chose to be. Hohenasperg is currently used as a psychiatric prison.

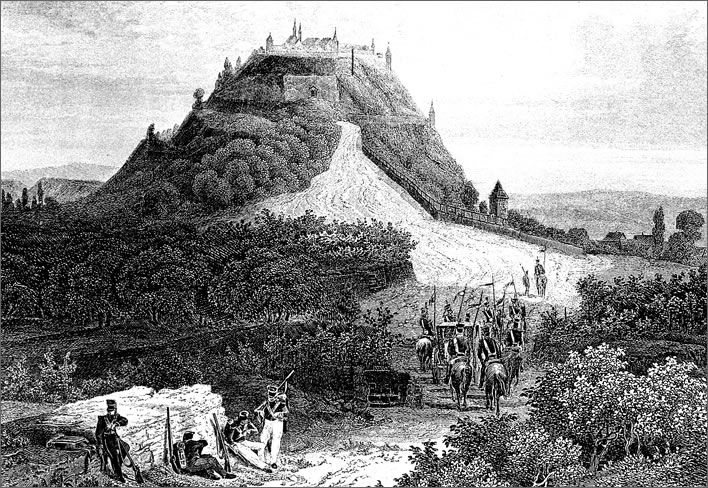

His relief faded, though, when he found out that he was to be kept in close confinement there. At first light on Friday 24 January, the company set off again. They stopped about 30 kilometres later in Cannstatt, where Schubart at least had enough appetite to eat something. After lunch they set off again, covering the 20 kilometres by mid-afternoon. As they approached Asperg, the hill crowned by the fortress loomed out of the winter sky.

A VIP reception

When he arrived in the courtyard of the fortress and was being taken to his dungeon, a hole near the base of a tower on the inside of the massive walls, Schubart noticed something quite remarkable: the Duke and Franziska were watching from a window.

The pair had taken the trouble to travel along the winter roads just to watch his imprisonment. Carl Eugen may even have chosen Hohenaspberg over the distant fortress of Hohentwil because of its proximity to Ludwigsburg. It was certainly easier for him and his mistress to witness in person the spectacle of Schubart's downfall. This act of vengeance was very personal indeed for them – both of them – and it would be ten long years before Schubart would be freed and only then after considerable pressure from Prussia.

Hohenasperg in a representation from 1820 and from 1850. From the promenade on the walls there is a remarkable view out over the surrounding fertile plains. There are vineyards on the hillsides. The locals, with dark Swabian humour, joked that Hohenasperg must be the highest hill in Germany because it takes so long to get down from it.

Modern German accounts of Schubart's incarceration reflect the political viewpoint of their authors, which, in the German school system, usually mean viewpoints we might characterise as 'left-wing progressive'. From such a viewpoint, Schubart's imprisonment was an act of arbitrary, extra-judicial power by a feudal ruler against a brave political journalist.

But as we have just noted, the presence of the Duke and Franziska at Schubart's imprisonment and the lengths to which they must have gone to be on that hill fortress in the depths of winter show this was no simple silencing of a journalist. Nor must we forget the words that Schubart put into Carl Eugen's mouth in his conversation with General von Ried, that he had 'not a few reasons' to want him silenced. Schubart, writing his autobiography in prison, wisely refuses to give us details of these many reasons. However, we only have to consider the moral imprecations contained in the arrest order to see that Schubart is not just an unwise political journalist. There were deep personal motives at play which certainly involved Franziska. Why otherwise would Carl Eugen drag not just himself but also his mistress through the winter cold but to enjoy this delicious moment when the detested Schubart is thrown into his dungeon?

The dungeon decade

We don't have space here to go into any details about Schubart's incarceration on Hohenasperg. He was finally freed in May 1787. The reasons behind the duration of his imprisonment, the details of the 'brainwashing' and 're-education' procedures to which he was subjected and the reasons for his final release we have to leave untouched. Perhaps another time. All we need to know is that in the middle of his incarceration, sometime around 1782 or 1783, at a time when he was not allowed to write, Christian Schubart wrote a poem entitled Die Forelle, that described everything that had happened to him during that cold January in 1777.

References

-

^

The text of the Ducal edict is translated from David Friedrich Strauss, Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubarts Leben in seinen Briefen, Bonn, 1878, vol 1, p 250f.

The source of the edict is in the Hauptstaatsarchiv Stuttgart, A 313, Bü 16. A modern transcription can be found in Herbert Hummel und Thomas Scheuffelen, Schubarts Verhaftung in Blaubeuren, Marbach, 2002, p. 8f. - ^ After news of Schubart's arrest spread Scholl found himself to be a detested man. He wrote to Carl Eugen urgently asking for a transfer for his safety. A note in the margin of Scholl's letter suggests that he would be moved 'at a convenient moment'. The moment never arrived and Scholl remained in Blaubeuren for the rest of his life. A modern commentator notes that putting one's trust in absolutists is always a risk better avoided.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!