The community under siege

Richard Law, UTC 2016-03-04 07:13

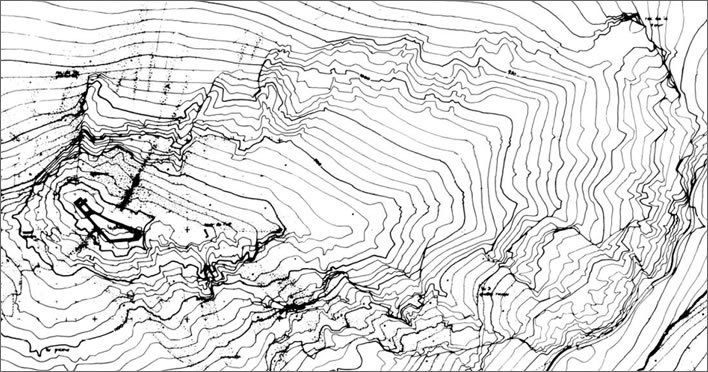

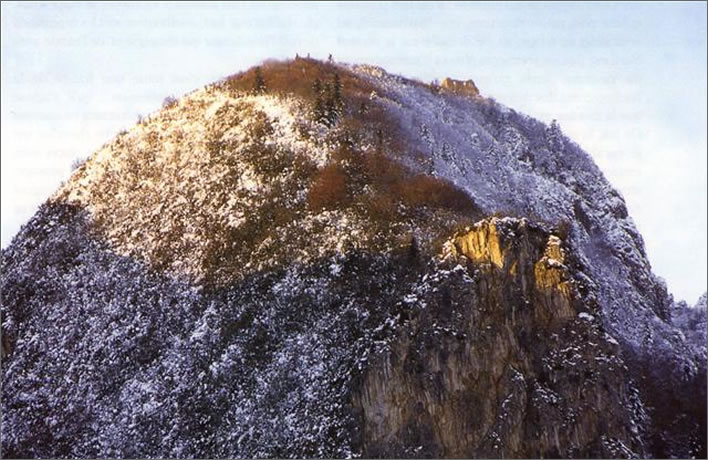

Montségur is a steep-sided limestone hill in the foothills of the Pyrenees in south-west France. Its highest point is a small plateau (about 200 metres above the valley, 1208 metres above sea level). From the plateau a thickly wooded ridge runs for about 800 metres north-eastwards, descending steeply to a flat-topped pinnacle, the 'Roc de la Tour' at 900 metres.

A view from the normal footpath looking up to the ruins of Montségur III, built after the destruction of the Cathars' final settlement Montségur II.

The path weaves between the ruins of defensive walls.

A view from the footpath down to the modern village of Montségur.

Starting around 1206, under the protection of the local feudal rulers, the Cathars had built a village in this improbable place, right on the high plateau at its peak. There was a central fort around which houses had been built, the outer ones on terraces that were built out to expand the level space on the plateau. The village and also its inner fort were both known as the 'castrum'. This village is known to archaeologists as Montségur II. It replaced an earlier village, Montségur I, of which there is now no trace. A third fortress, Montségur III, became the ruins we see today.

An aerial view from the north showing the remains of the terraces on the right that formed the foundations for the houses of the castrum.

The remains of foundations for the houses on the outer edge of the castrum.

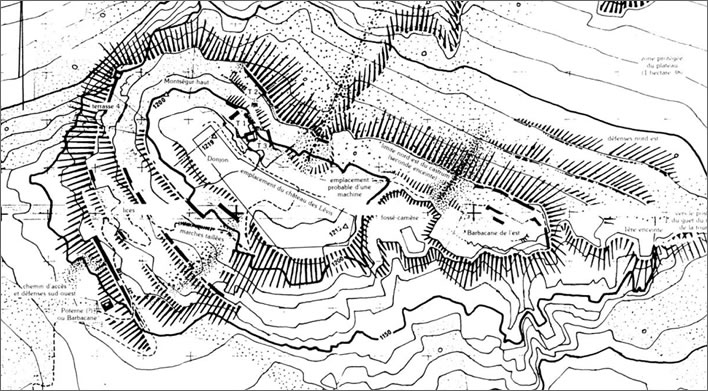

A plan of the castrum. At the bottom left the path zig-zags through the defensive walls. The walls had a stone base topped off with wooden pallisades. The route down the ridge to the Roc de la Tour begins on the far right.

The principal access from below is a steep track that zig-zags up the western side of the main hill. If the defenders are not firing crossbow bolts or throwing rocks at you, the ascent will take a normal person a good half hour. The Cathars had built two rows of defensive ramparts with wooden pallisades across this path.

There were other routes that the Cathars knew about, barely goat tracks only suitable for the sure of foot and balance. One, called the 'thieves' track', squiggles its way down the rock face and is really only suitable for someone who is tired of life or indeed a 'Friend of God'.

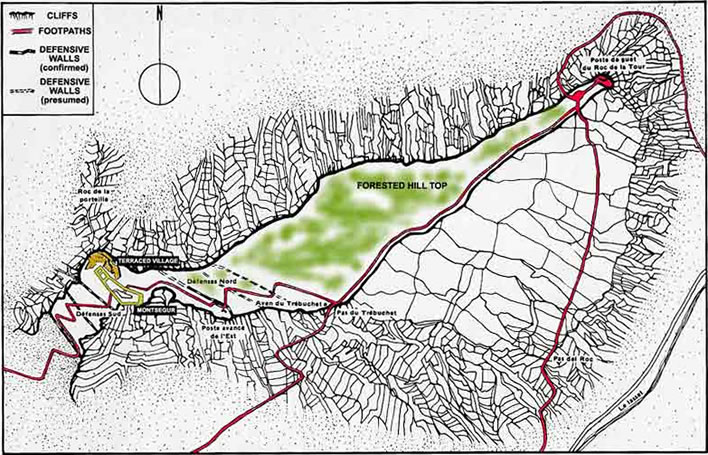

On the top of the Roc de la Tour, the 84 metre pinnacle at the other end of the ridge, the Cathars had erected a guard tower allowing them to keep distant watch over the entire countryside for enemy activity. As it turned out, it was enemy activity only 20 metres away that they should have been watching. A track along the ridge connects the castrum to the watchtower.

A reconstruction of the castrum as it was in Montsegur II, the Cathars' final stronghold.

There is a good 3-D reconstruction of the castrum on the video page.

A reconstruction of a building on the edge of the castrum, clinging above the cliff face.

Montségur became the fortified village home to the leaders of the Cathar church in the region. The sources state that during the time from its creation to its destruction more than a thousand people had resided on Montségur.

Over a period of thirty years Montségur had survived three sieges: one in 1212 during the Albigensian Crusade by Guy de Montfort, Simon's brother; the second in 1213, this time by Simon de Montfort himself; the third in 1241, a half-hearted effort by the local feudal lord, Raymond de Toulouse. The assassination of several members of the Inquisition in 1242 in nearby Avignonet by a small force based in Montségur was the last straw.

Stalemate

From about May 1243 this stronghold was besieged by an army of unenthusiastic local conscripts, fanatic Catholics and Gascons from the region. It is often stated that the besieging army was 10,000 strong, but such a large number is not credible. The logistical problems alone of recruiting such a large number of men in a relatively hostile area and supporting them during a siege put this figure into question. After all, the action would not be a land battle between opposing armies on some 'darkling plain': after a point, additional manpower would just be a useless burden.

At the time of the siege there were about 361 tightly packed occupants in Montségur's fortified village, 150 of whom were not cenobites.

An early half-hearted attempt to storm the defences in a frontal attack up the path was predictably repelled with minor losses for the defenders. The attackers settled down to a siege that they hoped would starve the Cathars out. The months went by and it became clear that the Cathars had plentiful reserves.

The one thing that worked in the attackers' favour was a mild winter. In less balmy times the winters in these eastern foothills of the Pyrenees could be ferociously hard. However, the December of 1243 was exceptionally mild.

Who dares, wins

Sometime before Christmas 1243 a small, lightly armed 'commando group' of the attackers – probably the sure-footed Gascons – managed to force a route around the base of the pinnacle at the eastern end and climb by night up the less precipitous ground at the back of the pinnacle up to the base of the watchtower. The guards, taken completely by surprise, possibly still in their sleep, were put to the sword. Even in that stille Nacht what cries and screams came from the watchtower were probably unheard in the castrum, where the occupants slept on, unaware that their fate had been sealed and that the beginning of the fiery end for them had arrived.

The route was certainly daring, thus even more unforeseen: 'Who dares, wins' indeed. Our only source of information about this escapade, the chronicler Guillaume de Puylaurens, tells us:

Day came […] and they saw with astonishment the terrifying route by which they had ascended during the night – they would have never dared to do this in broad daylight.

A contour map of the 'pog' on which Montségur stands. The castrum is on the left. The route of the normal path can be seen zig-zagging through the defensive walls up to the castrum. The Roc de la Tour is top right. The levelling out of the terrain just behind the pinnacle can be seen, as well as the steep ridge that runs from there up to the castrum.

A view of the Roc de la Tour. The attackers' route curved round behind the pinnacle and up the ridge on the right.

A view of the Roc de la Tour and behind it the ridge leading up to the castrum.

A view in winter, as it would have been in December 1244.

Looking down from the ridge into the valley a long way below. The small bump coming out of the hillside is the top of the Roc de la Tour.

The anatomy of the assault

Let us dispose of this added drama: the facts are dramatic enough. It is inconceivable that the assault team would have launched themselves unprepared into an unknown ascent in darkness: no commander would have risked throwing his best chance of breaking the siege by allowing a few locals to charge up a goat track and, in case of failure, alert the defenders to this weakness. There would have to be planning and preparation.

The full moon fell on 27 December in 1243, so, assuming clear skies, the surrounding terrain was moonlit from the middle of December. The bright moon may have been a reason for the timing of the assault but we should note that the route they took was up a gully on the north side of the hill and so would have been in moon shadow.

Unless they were blindly following someone who knew the way intimately it seems reasonable to assume that they had explored the possibilities of the route by daylight some days before, perhaps even preparing it quietly with fixed ropes or ladders. The route itself is barely visible from the watchtower. For the attackers the logic of the assault was compelling: at the watchtower the hill was at its lowest and we can assume that a pre-existing goat track marked their way.

Eight centuries of erosion have left their mark, but even then the route around the back of the pinnacle was not formidably steep. We shouldn't be too carried away by the chronicler's dramatic tale of a hair-raising ascent. Even so, were it not for the appalling fate of the inhabitants when the siege was finally raised, the audacity of the attack would be a celebrated event in military history.

The details of the techniques that were used to make the 'terrifying' route passable to normal soldiers and equipment are unknown. The first assault was only the beginning, intended to kill the guards in the watchtower. The success of the assault depended on a rapid follow up of men and equipment. We can imagine that, after the watchtower had been neutralised, the commando group set up ladders and fixed ropes that not only allowed reinforcements of normal soldiers to be brought up but also, piece by piece, a battery of siege catapults.

Footpaths and the attack route.

There seems to have been resistence – crossbow bolts have been found in this area – but the attackers fought their way up and along the very steep ridge, over and past outcrops of rock, to a point where they could assemble the catapults.

Siege engines in the air

The ridge becomes gradually less steep as it approaches the village, but the total height difference between the watchtower and the village is still a considerable and steep 300 metres. The closer the catapults were to the castrum and the smaller the height difference the better.

The Cathars had not left the eastern approach to the village completely undefended: quarrying had created a dry moat with (possibly) a drawbridge and behind that they had built a fortified gate that would have been difficult to storm by infantry alone. They seem never to have imagined that they would be facing siege engines hurling rocks at them. That lack of imagination would be their undoing.

The defenders also had at least one catapult, but the attackers offered no major structures against which they could use it. Stone balls, weighing between 20 and 80 kilograms, were quarried from the limestone of the top of the hill. There were even small balls of around 5 kilograms that were thrown in clusters. There was an endless supply of ammunition from the quarry, allowing the attackers to subject the village to a relentless bombardment, a spectacle carried out 200 metres above the valley. Archaeologists have found around 20 balls in the area of the castrum.

Limestone balls for a siege engine.

Sometime before 14 February the attackers launched an assault with ladders on the battered eastern defences of the castrum, an assault which was only repelled with great difficulty and with serious losses for the defenders. At that point it was clear that the Cathars had lost. Their village and fort were being steadily reduced to rubble. Further resistence would undoubtably end in a massacre of everyone in the village, not just the cenobites.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!