Gretchen am Spinnrade

Richard Law, UTC 2016-06-13 17:41

Let's take our minds off all the troubles of the world – particularly this EU Referendum nonsense in the United Kingdom – and consider something really important: Franz Schubert's Lied Gretchen am Spinnrade (Op. 2, D 118 ), composed in October, 1814, nearly 202 years ago.

Schubert was seventeen when he wrote it – I repeat for the speed readers among you: seventeen , an age at which many modern children are just wondering about how to spend their 'gap year'. It was one of the first songs he wrote at the start of a monumentally productive phase of songwriting (1814-1817) and has been called a 'stroke of genius of the first order'.[1]

We Schubert fans have to note yet again – wearily yet again – that this magnificent piece brought assistant school teacher Schubert scarcely any money and only local recognition. It was finally published in 1821, seven years after its composition. Within another seven years Franz would be in his grave.

Back to the text

In order to appreciate just what a 'stroke of genius' the composition was we have to understand Schubert's starting point, the text on which his composition was based. If there is one thing we have learned in our consideration of some of his other pieces –Zögernd leise,Winterreise,Die schöne Müllerin– it is that Schubert was a skilled, extremely sensitive and perceptive reader of a poem. The excisions and emendations he makes in adapting texts to music are evidence enough for that. He was usually able to make something out of mediocrity, but give him a quality text and he would soar.

With the text for Gretchen am Spinnrade he needed to do nothing. It is a piece from the master himself, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), taken from his world-famous play Faust.[2] The text embodied the same literary perfection that we met in Goethe's Nähe des Geliebten, a poem that was another worthy starting point for the musical intelligence of Franz Schubert.

In the present case, that musical intelligence caused him to alight on the monologue Meine Ruh' ist hin , 'My peace of mind has gone', spoken by a young woman, Margarete ('Gretchen'), whilst she is working at her spinning-wheel.

The spinning-wheel scene is a key moment in the development of the plot. We cannot understand Margarete's verse monologue and its important role in the play unless we have an idea at least of what the play is about and some knowledge of the events that precede and follow this scene. I'm sorry, but there is no escape: you are in for Faust, the Executive Summary.

I can only hope that Goethe scholars, particularly that gloomy lot the Faust specialists, will not drag me off to Hell when I now 'do' Faust in a few paragraphs, leaving out everything that is not of direct relevance to Gretchen's monologue.

In Heaven

The play begins with a prologue set in Heaven. The three archangels, Raphael, Gabriel and Michael approach the Lord and give him a glowing report in flowery, poetic language of the state of the world: 'all your great works are as wonderful now as they were on the first day'. You can see why they got to the top of their profession.

Mephistopheles[3] approaches. Whereas the three archangels had simply reported on the state of the inanimate world, Mephistopheles reports on the state of the humans – 'the little god of the world' – who misuse their God-given reason and have made no progress at all.

The Lord, irritated by Mephistopheles' permanent bad opinion of the human race, presses him on a specific case: 'Do you know Faust, my servant?'. Mephistopheles says that of course he does, but currently Faust is being driven mad by his obsessive search for knowledge. God says that he will soon intervene and lead Faust back to clarity.

What do you bet, says Mephistopheles, that I can lure him down my path instead? The Lord tells him that as long as Faust is on earth, Mephistopheles is free to tempt him. Mephistopheles is delighted to hear this: he much prefers to play the 'cat and mouse game' with living humans than spend his time just persecuting the souls of the dead. Then he's all yours, says the Lord, but you will be embarrassed when you have to accept that a good person is aware of the path of righteousness.

Faust, Mephistopheles and their pact

In the next scene we meet the man himself, Dr Heinrich Faust, polymath scholar. He is currently in the middle of a severe mid-life crisis. He is making no progress in his studies, he is getting old and his personal life is bleak. He is deeply depressed, tired of life and on the verge of suicide.

Mephistopheles appears to him.[4] After some discussion Mephistopheles proposes a pact: Mephistopheles will serve Faust and bring all his wishes to fulfilment, but as soon as Mephistopheles succeeds in making him contented and happy, capable even of idleness, Faust's soul will be his, he will die and have to serve Mephistopheles in Hell. Faust accepts the offer.

After some further scenes Mephistopheles takes Faust to a witches' kitchen, where he drinks a magic potion that makes him younger and attractive to every woman. It will also have an effect on him: he will see 'a Helen in every woman'.

Goethe's inspiration for the witches' kitchen scene: Pieter van der Heyden after Pieter Bruegel the Elder, St. James and the Magician Hermogenes, 1565.

On the principle that a picture is worth a thousand words, this should save us a paragraph or two.

The victim appears

Emerging into the street, the first woman Faust sees is Margarete, returning from confession. He is utterly smitten by her, accosts her in the street and offers to walk her home on his arm. His offer, shockingly forward and completely socially inappropriate, is rejected. Margarete's modesty and pious chastity only serve to inflame him more. She goes on her way.

Franz Xaver Simm, (1853-1918): Faust meets Margarete in the street. Image: source.

Faust demands of his 'servant' Mephistopheles that he obtain this woman for him immediately, or their pact is broken. Mephistopheles counters by saying that this woman is so virtuous that he will need weeks to corrupt her. For the moment Faust should just be content with leaving a gift in her room.

Margarete, although her modesty repelled Faust's indecorous advances in the street, was impressed by his noble appearance and manners. Taking a first step down the slippery slope, she interprets the self-assured forwardness as a sign of aristocratic breeding rather than the behaviour of a geeky, sex-starved philosopher with a demonic love-potion inside him. Her initial fascination with Faust is the first sign of her corruptibility.

Mephistopheles takes the besotted Faust to Margarete's room while she is out. Faust is even more impressed when he sees the clean and orderly state of her room, her physical cleanliness being a metaphor for her spiritual cleanliness.

Mephistopheles conjures up a box of jewellery, which they leave in the cupboard in her room. Returning, Margarete disrobes, opens the cupboard to hang up her clothes and finds the box of jewellery. She stands at the mirror, trying on the necklace, earrings and brooches. Another step down the slope, but her conscience is still able to make her realise that there is something wrong about the sudden appearance of this treasure.

The scene changes to a street, where we find Mephistopheles and Faust in conversation. Mephistopheles tells Faust that Margarete showed her mother the treasure. She, too, thought that it could not have been come by honestly and so they handed it over to the local priest for the use of the Church. Mephistopheles is outraged at the thought that he has just enriched the Church, noting bitterly that the corruption of the Church is so great that they will accept treasure without needing to know where it has come from, even, as in this case, from the Devil himself.

Faust orders Mephistopheles to get another, more valuable treasure and to involve Margarete's neighbour and friend, Martha, as an innocent go-between in the seduction.

Martha the neighbour

Martha's husband has gone missing in Italy. She would like to know whether he is still alive. If he is dead, she can go looking for another husband.

Margarete turns up and shows her the second box of treasure. Martha tells her not to take it to her mother this time. Margarete is seduced by the jewellery and the two ponder how she could keep the treasure. Wearing it openly would be impossible. Margarete could perhaps keep the jewels at Martha's house and just come over to wear them there in secret.

Margarete still thinks the treasure cannot have been come by honestly, but, confronted by these wonderful jewels, her resistance has faded. Step by step, rationalisation by rationalisation, she moves down the slope of compliance.

Mephistopheles enters and brings Martha the longed for news that her husband is dead. To hand over the death certificate he requires two witnesses. For this purpose he will bring Faust and Martha will invite Margarete. When Faust hears that he is required to give false witness of the death of Martha's husband he briefly refuses, but Mephistopheles easily persuades him. His desire for Margarete overwhelms all other moral considerations: lust is overcoming all scruples in both Faust and Margarete.

The four meet and walk in Martha's garden. Martha, the new widow, makes advances at Mephistopheles while Faust and Margarete become ever closer.

Franz Xaver Simm, (1853-1918): Faust and Margarete in the garden. Image: source.

As they talk in the garden Faust learns even more of Margarete's piety and humility. She picks a Sternblume [an aster or marguerite(!)] from the garden and tortures it in the traditional way lovers do by ripping its petals off, one by one: 'he loves me, he loves me not', ending on 'he loves me'. Faust, the studious geek, has never come across this ritual. He is tormented by desire.

Faust and Gretchen retreat to the pavilion and kiss, but are interrupted by Mephistopheles, who tells Faust it is time to leave. Margarete refuses to let Faust accompany her home, because her mother would see them, so taking yet another step down the slope of deceit. Faust and Mephistopheles depart, leaving Margarete asking herself what she, a 'simple, ignorant child', has done to find the love of such a wonderful man. Her fate is sealed.

Faust realises that he cannot resist his passion for Gretchen, even though her seduction by devilish powers will drag them both to hell.

Gretchen in the tempest

Now we see Gretchen alone in her room, sitting at her spinning wheel. Her calm, untroubled, modest, dutiful and pious life is gone. Now she is left only with turmoil and tumultuous passions. Her monologue makes it apparent what Mephistopheles and Faust have done to her – how far she has fallen to a deep point from which there can be no way back.

| Meine Ruh' ist hin, Mein Herz ist schwer, Ich finde sie nimmer Und nimmermehr. |

My peace of mind has gone, my heart is heavy, I'll never find peace again, never again. |

|

Wo ich ihn nicht hab

Ist mir das Grab, Die ganze Welt Ist mir vergällt. |

When I don't have him, that is like a grave to me, the whole world is bitter for me. |

|

Mein armer Kopf

Ist mir verrückt, Mein armer Sinn Ist mir zerstückt. |

My poor head is crazed, my poor mind shattered. |

|

Meine Ruh' ist hin,

Mein Herz ist schwer, Ich finde sie nimmer Und nimmermehr. |

My peace has gone, my heart is heavy, I'll never find peace again, never again. |

|

Nach ihm nur schau ich

Zum Fenster hinaus, Nach ihm nur geh ich Aus dem Haus. |

Only for him do I look out of the window, Only for him do I leave the house. |

|

Sein hoher Gang,

Sein' edle Gestalt, Seines Mundes Lächeln, Seiner Augen Gewalt, |

His tall walk, his noble appearance, the smile of his mouth, the power of his eyes, |

|

Und seiner Rede

Zauberfluß, Sein Händedruck, Und ach, sein Kuß! |

and the magic flow of his speech, the press of his hand and, oh, his kiss! |

|

Meine Ruh' ist hin,

Mein Herz ist schwer, Ich finde sie nimmer Und nimmermehr. |

My peace has gone, my heart is heavy, I'll never find peace again, never again. |

|

Mein Busen drängt sich

Nach ihm hin. Ach dürft ich fassen Und halten ihn, |

My bosom draws me towards him. Oh, if only I could seize and hold him |

|

Und küssen ihn,

So wie ich wollt, An seinen Küssen Vergehen sollt! |

and kiss him, just as I want, melting in his kisses. |

Let's unravel some of the subtleties in these lines.

- The style of language used reflects the character of Margarete: the vocabulary and expressions are simple, uncontrived; the sentences are short. When the more complex characters in the play deliver monologues – Faust, Mephistopheles and the Archangels, for example – they do so in a complex style. Margarete, in contrast, speaks to us with the voice of a 'simple, ignorant child'.

- We should note Goethe's skill in handling short, rhymed lines – always a severe test of poetic talent. Readers may remember how lacking in that talent we found Friedrich von Matthisson. Goethe's short lines not only pick up the rhythm of the spinning-wheel but they can all be spoken in clear language without affectation. The rhyme scheme does not jar or feel contrived.

- At this point in the play Goethe wants to show how totally besotted with Faust Margarete has become. As such, it is a defining moment of the plot. Putting the lovestruck girl at a spinning-wheel is a stroke of Goethe's genius, creating a metaphor for her state of mind: restless, disturbed, seething with longing and sexual passion.

- Another mark of Goethe's genius is the division of the monologue into three sections, each introduced by Meine Ruh' ist hin . The first section reveals the turmoil of Margarete's distraught condition, the second tells us of the wonderful qualities of Faust in her eyes, the third expresses her deep physical longing. Goethe is a master of using structural form to intensify the meaning of the text, as we also noted in an earlier post.

- The third section does not describe some vague mental yearning: this is full-blown physical desire. In the present text we have to make do with the delicacy of Margarete's Busen, 'bosom'. When we look at the same poem in the Urfaust, written thirty years before but never published, we find the young Goethe was more explicit: Mein Schoos! Gott! drängt / Sich nach ihm hin 'My vagina! God! thrusts itself after him'. Vagina, womb, vulva, uterus – all are possible. Our more sensitive readers my prefer W. B. Yeats' formulation of the same phenomenon in 'Under Ben Bulben': Michael Angelo left a proof / On the Sistine Chapel roof, / Where but half-awakened Adam / Can disturb globe-trotting Madam / Till her bowels are in heat.

The musical genius

Franz Schubert, the seventeen year-old assistant teacher, saw the potential of Gretchen's monologue clearly, caught the rhythm of the spinning wheel just as Goethe had done: the thrust of the pedal, the oscillation of the wheel, the pulling out of the thread. He caught the build up of passion over the three sections and set the climax at Und ach, sein Kuß!, 'and, oh, his kiss!', following it with a long vocal pause while the wheel rumbles on. He did not need to clean up Goethe's text but – the musical genius at work – he enhanced it for his musical purpose, adding, for example, the repetition: 'ich finde, ich finde sie nimmer'.

A number of musicologists have written about the musical complexities of the piece: its overlaid rhythms, its subtle stretchings and compressions, its unexpected harmonies. All this is beyond our scope in this post. Schubert himself seems to have been aware of what he had achieved in Gretchen am Spinnrade. It was usual to group shorter pieces together under a single opus number. The two great Schubert/Goethe masterpieces Gretchen am Spinnrade (Op. 2) and Erlkönig (Op. 1) were given individual opus numbers.

But, as we know, the young composer never received widespread recognition during his lifetime and almost faded from memory for several decades after his death. Even when his friends sent a collection of his songs to Goethe himself in April 1816 there came no answer from the great man. Another set of songs Schubert sent to Goethe in June 1825 went unanswered. Only after Schubert's death – how often Schubert fans have to write that phrase! – did Goethe hear the Erlkönig performed for him and accepted that the words and the music created a 'visible picture'.

Completing the tale

Margarete's monologue Meine Ruh' ist hin is a key passage in the play, a passage in which Goethe presented the moment that she was overcome by her passion for Faust, the moment of her doom. From this moment the action of the play turns and spirals downwards through one evil after another until it ends in tragedy. We now only need a paragraph or two to follow the plot from there to its catastrophic conclusion.

Faust finally beds Margarete, although we are not told this explicitly. In order to facilitate the encounter Faust gives Margarete a sleeping potion to administer to her mother, thus allowing the beast with two backs its uninhibited and noisy delights. The potion turns out to be poisonous and puts her mother to sleep in the veterinary sense.

Margarete becomes pregnant. Challenged by her outraged brother, Faust and Mephistopheles kill him in a swordfight. She goes insane and when the baby is delivered she drowns the newborn child. She is arrested and sentenced to death.

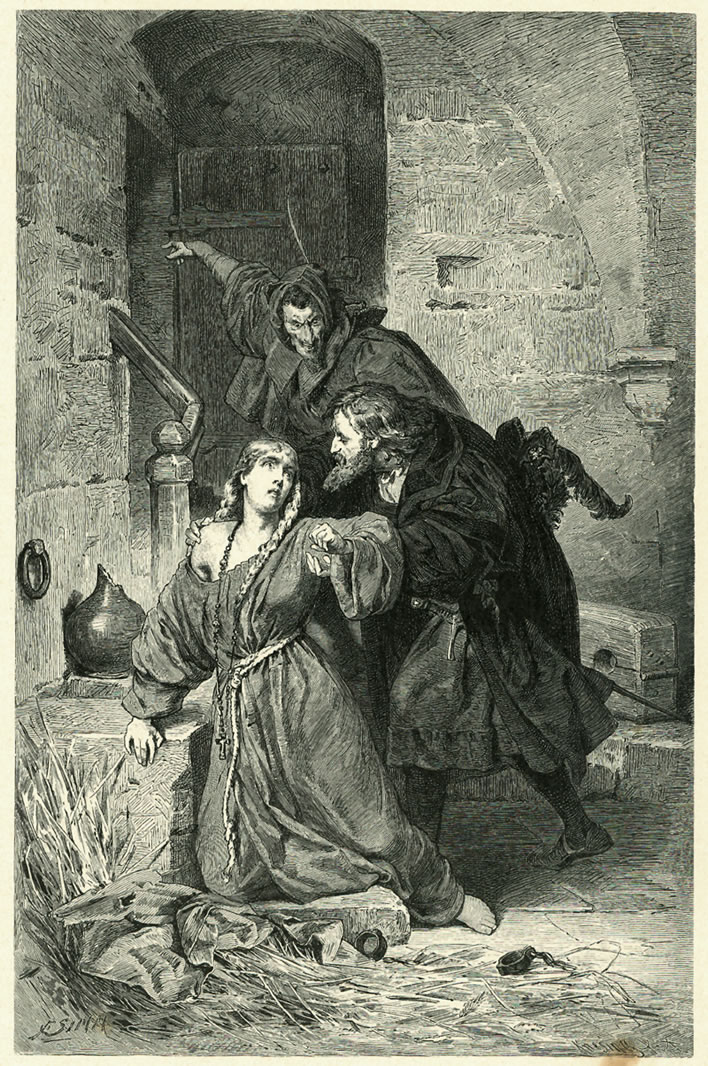

Franz Xaver Simm, (1853-1918): Margarete, Faust and Mephistopheles in the dungeon. Image: source.

Faust and Mephistopheles, the two who are ultimately responsible for this chain of evil that has led to three deaths and so much misery, visit Margarete in her dungeon and offer her the chance to flee with them. She's had enough: faced with this shifty pair and in an agony of guilt she chooses to stay in prison and face her mortal end. She will be tied to a chair and beheaded. As Faust and Mephistopheles flee the dungeon, a voice from Heaven announces her eternal salvation, which will come after the death penalty has been carried out.

Performing Gretchen am Spinnrade

Can we say that an appreciation of the Faustian context of the text is essential to a satisfactory interpretation of the song?

Without doubt. A competent singer and a competent pianist can usually turn in a pleasant performance. For a good performance however, the singer and the pianist have to capture the obsessive, physical passion of Margarete. If the performers approach it as just another song without appreciating its context, mediocre is all their performance will ever be.

They also have to take account of the three sections of the text we identified above: Goethe applied this structure deliberately; Schubert perceived the structure and put it at the heart of his setting. Let's review them again:

- The first section is a complaint at the emotional turmoil that Margarete is now suffering – her former quiet, pious and orderly life has been shattered. A smooth legato doesn't cut the mustard here.

- The second section is opened with a repetition of the complaint, but then moves to being a catalogue of the marvellous qualities of her lover. The turmoil seems to be worth it. On 'his kiss' we expect an orgasmic climax without the sound of shattering glass. The accompaniment continues alone to allow the singer to recover.

- The third section also opens with a repetition of the complaint, but then quite explicitly describes her physical desire for him. We have thus arrived at the source of the turmoil in her life: lust. Can there be any doubt that the act of darkness will take place soon?

The outstanding and not merely pleasant performance has to capture all this – a difficult task. The singer is posted next to the piano in a nice frock, is concentrating on enunciation and a smooth melodic line. Some singers take it slowly, lingering over the opportunities to make beautiful noises; some substitute volume for emotion, endangering windows; very few register Margarete's passion.

My preferred version on YouTube is a performance from 1961 by Christa Ludwig (1928-) and Geoffrey Parsons (1929-1995). I don't think of Margarete as a mezzosoprano, but Ludwig's performance is good enough to make me forget that problem. She and Parsons do not hang around and his playing is precise and clear.

I won't linger over the various mediocre performances there are: nice voices, nice frocks – but no Schoos.

References

- ^ Krenek, Ernst, Franz Schubert: Ein Porträt, Tutzing: H. Schneider, 1990, p. 6.

-

^

There are three Fausts:

The Urfaust, unpublished, 1775 and a development of it, Faust. Ein Fragment, published 1790.

Faust. Eine Tragödie, published in 1808 and usually abbreviated to Faust I.

Faust. Der Tragödie zweiter Teil, published completely in 1832 after Goethe's death and usually abbreviated to Faust II.

When in the present text we write just Faust we mean Faust I. - ^ The name 'Mephistopheles' is an invention of Goethe's. The traditional names 'Satan' or 'the Devil', although they are implicit, are rarely used in Faust. The 'God and Mephistopheles' theme in Faust is reminiscent of its analogue in the Biblical Book of Job, which reaches back to a very early conception of Satan as the 'angel gone wrong'. The similarities and differences between the play Faust and the Book of Job are fascinating but too extensive to be dealt with here.

- ^ We have jumped over the scenes before Mephistopheles' entrance and the mode and details of his manifestation, they are not relevant to us here.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!