The fine art of wonderment

Richard Law, UTC 2016-06-22 11:22 Updated on UTC 2016-06-25

The solstices, summer and winter, and the equinoxes, spring and autumn, are a cause for wonder – astonishment, too. We think in awe of the immense celestial mechanics of which we tiny beings on our tiny, tilted planet are a part. We may recall Feynman's cutting insight into the inadequacies of religious narratives: 'the stage is too big'.

The more earthbound of us may just gaze in wonderment on people who dress in bedsheets, wreathe their foreheads with ivy and miss valuable sleep to greet the dawn on the summer solstice. These infinitesimal dust mites are happy in their firm belief that the celestial immensity is there just for them. But we should not deny them their own wonder, too, as the sun rises between the stones.

Wonder, astonishment, surprise – whatever you want to call it – is the starting point for all philosophical questioning. Plato (428?-348? BC), through the mouth of Socrates, described that to the young Theaetetus:

For this feeling of wonder shows that you are a philosopher, since wonder is the only beginning of philosophy, and he who said that Iris was the child of Thaumas made a good genealogy.[1]

Iris is the messenger of heaven in Greek mythology. Plato interprets the name of her father Thaumas as 'wonder' (Thauma, θαῦμα), leading to the 'good genealogy' – 'good' in Socrates/Plato's opinion because the messages of the gods are always a source of wonder.

His happy aside about Iris provides us with a useful excuse to look at these famous irises of Vincent van Gogh, painted in the psychiatric hospital at Saint-Rémy – in their own way messages from the gods that cause wonder to mortals, whether artists or viewers:

Vincent van Gogh, Irises, 1890. Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Vincent van Gogh, Irises, 1889. Image: J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

Vincent van Gogh, Irises, 1890. Image: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Aristotle (384-322 BC), the plodding explainer, added some verbal ballast to Plato's charming simplicity:

It is through wonder that men now begin and originally began to philosophize; wondering in the first place at obvious perplexities, and then by gradual progression raising questions about the greater matters too, e.g. about the changes of the moon and of the sun, about the stars and about the origin of the universe.[2]

But Plato and Aristotle are not really talking about the same things.

Plato's idea of wonder at the messages of the gods, the start of all philosophy, would pass down through his followers in the idea of mania, divine madness and its consequences: revelations, visions, fire, light, excitement and altered states of perception. Plato's happy excitement has motivated and inspired Platonists and Neoplatonists in this way down the ages.

It's fun being a Platonist. The world is full of wonders – exciting, thought-provoking wonders. Confronted with a jug of irises, the Platonic mind picks up a brush and paints these wonderful things, creating, in so doing, another message, another wonder.

In contrast, Aristotle writes for pedestrian puzzlers, whether of crosswords or black holes. Confronted with a jug of irises, the Aristotelian mind puzzles a while, pulls the flowers apart, counts their petals and stamens before ordering them within the species, families and genera of the plant world.

The Platonist observes a butterfly and stands in wonder at this thing, astonished at its mere existence; the Aristotelian catches it and sticks a pin through it.

Friedrich Hölderlin: the wonders of the night

The German poet Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843) was steeped in the symbolism of both the classical Greek and the Christian traditions. His work was arguably a century ahead of his time – his poetry is quite capable of holding its own against that of the 20th century modernists. But only a few knew of his verse during his lifetime and apart from them he was forgotten or ignored. Recognition only came towards the end of the 19th century.

His magnificent poem Brod und Wein, written around 1800, interweaves the two worlds of revelation from Christian and Bacchantic traditions. It consists of 160 lines of hexametric verse and is a taxing read even for educated native speakers. Grammar, syntax and Greek metrical measures are bent to his will. The poem is suffused with wondrous transitions: objects have layers of meaning in both worlds, the Christian and the Bacchantic; words themselves are multilayered, too. There is an enduring sense of wonder at the divine revelation of both traditions.

A few years after writing this poem he would be declared insane and spend his last thirty-six years in a room in a tower, looked after by a carpenter, Ernst Zimmer, and his family. That family had to put up with a lot from the deranged poet and any account of Hölderlin should mention the debt we owe to them for the patience, humanity and charity they showed their distraught lodger.

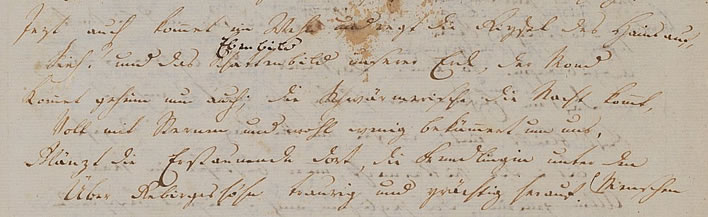

Six lines will give you a flavour of Hölderlin's Platonic sense of wonder.

Now a breeze also arises and stirs the treetops,

look! and that copy of our Earth, the Moon,

rises incomprehensibly too; the fantastic night comes,

full of stars and indifferent to us,

there the astonishing one shines down, the alien among humans,

sad and splendid above mountain tops.[3]

Friedrich Hölderlin, extract of manuscript fair copy of 'Brod und Wein' in Homburger Folioheft, 1802, [StA 2,90/591] online.

Or, as that other distraught genius, Vincent van Gogh, lingering in the lunatic asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence put it ninety years later:

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, 1889, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Image: Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Knut Hamsun: the wonders of the everyday

Knut Hamsun (1859-1952), the great Norwegian writer, expressed the same sense of wonder in his novel Pan (1894). The protagonist of the novel, Thomas Glahn, has withdrawn from the world and lives in the forest on his own. Here he is explaining his sense of wonder to the young girl he has befriended. Let's start, too, with the heavens.

In autumn, many a time there are shooting stars to watch. Then I think to myself, being all alone, What was that? A world seized with convulsions all of a sudden? A world going all to pieces before my eyes? To think that I – that I should be granted the sight of shooting stars in my life! And when summer comes, then perhaps there may be a little living creature on every leaf; I can see that some of them have no wings; they can make no great way in the world, but must live and die on that one little leaf where they came into the world.

"Then sometimes I see the blue flies. But it all seems such a little thing to talk about – I don't know if you understand?"

"Yes, yes, I understand."

"Good. Well, then sometimes I look at the grass, and perhaps the grass is looking at me again – who can say? I look at a single blade of grass; it quivers a little, maybe, and makes me think. And I think to myself: Here is a little blade of grass all a-quivering. Or if it happens to be a fir tree I look at, then maybe the tree has one branch that makes me think of it a little, too.[4]

The girl understands Glahn's sense of wonder completely, as Plato would have done, too.

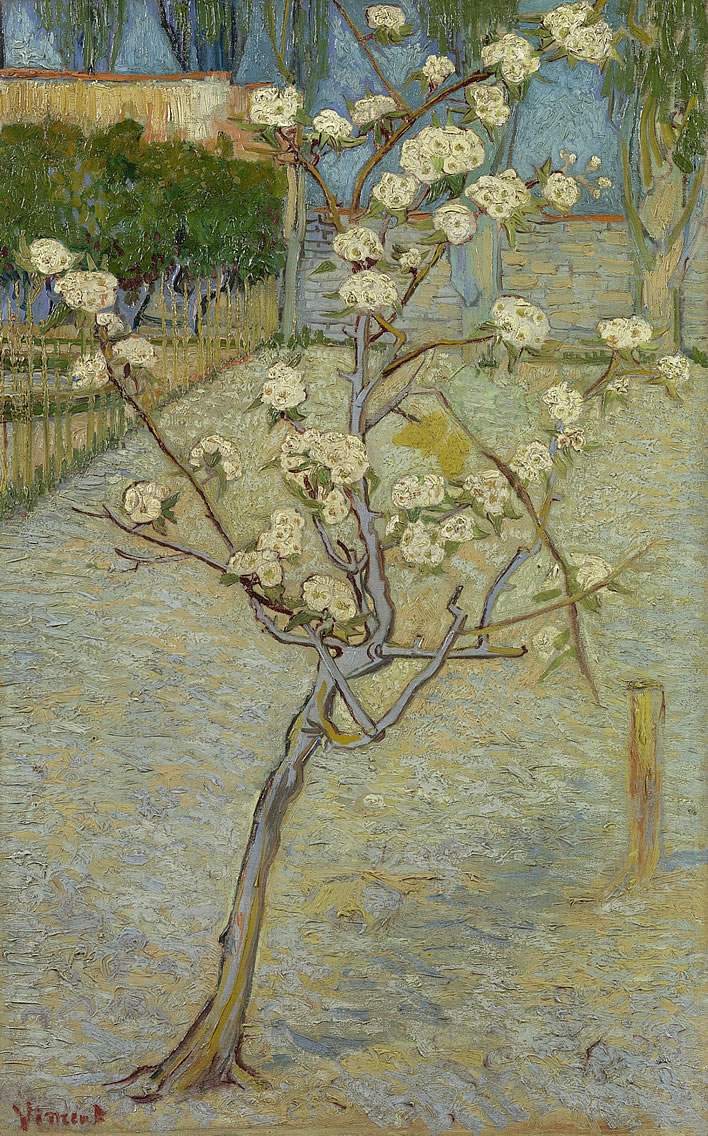

Vincent van Gogh, Small Pear Tree in Blossom, 1888, Arles. Image: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh, Undergrowth, 1889, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Image: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Hugo von Hofmannsthal: wonders beyond language

No doubt: Wonder is the prime mover of philosophy, its trigger as it were. It is not just the starting point for simple folk, but stands at the start of an intellectual journey that can begin at any time, even for the most sophisticated.

In 1902 the Austrian writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal (1874-1929) wrote an imaginary letter from the fictional Philip, Lord Chandos, to Francis Bacon (1561-1626) that described Chandos' withdrawal from the world of words to the world of wonderment. He had 'lost completely the ability to think or to speak of anything coherently'.

A watering can, a harrow left in a field, a dog in the sun, a poor cemetery, a cripple, a small farmhouse, each of these can become a receptacle of revelation. Each one of these objects and a thousand such others over which the eye would normally pass with indifference can suddenly at any moment – a moment which I am utterly powerless to evoke consciously – be stamped with such an exalted and stirring intaglio that words seem too poor to describe it. Yes, even just the mental image of an absent object, which has been selected by this incomprehensible process, becomes a receptacle that fills to the brim with this gently but steadily rising flood of godlike emotion.[5]

…

What had it got to do with pity, or with any comprehensible process of human thought when, on another evening, I found beneath a nut-tree a half-filled watering-can which a gardener's boy had left behind; and when this watering-can and the water in it, darkened by the shadow of the tree, and in it on the mirror of the water a beetle rowed from shore to shore – when this combination of trifles sent through me such a shudder at the presence of the Infinite, a shudder running from the roots of my hair to the marrow of my heels, that made me want to break into words which I know, were I to find them, would force to their knees those cherubim in whom I do not believe; and that I then silently leave this place and weeks later, catching sight of that nut-tree, I pass it by with a shy sidelong glance, not wishing to drive away the feeling of the miraculous that lingers there round that trunk, not wishing to drive away the unearthly shudders that still billow around that vicinity.

In these moments an insignificant creature – a dog, a rat, a beetle, a stunted apple tree, a track winding over the hill, a stone overgrown with moss – mean more to me than the most beautiful, compliant lover in the happiest night I have ever experienced. These mute and sometimes inanimate creatures are lifted up to me with such an abundance, such a presence of love, that my enchanted eye can find nothing in sight void of life. Everything, everything that exists, everything I can remember, everything touched upon by most confused thoughts, has a meaning.[6]

Vincent van Gogh, Garden of the Asylum, 1889, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Image: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Why does Hofmannsthal address his letter from the imaginary Chandos to the historically real Bacon? Bacon was the great proponent of empiricism and the modern scientific method. His mind is, taking our earlier definitions, that of an Aristotelian, not a Platonist. Hofmannsthal's Chandos, formerly a fluent writer, has now reached a point where words and rationality all fail him. His understanding of the world is now a Platonic, revelatory, artistic understanding.

Hofmannsthal is writing at a moment in European culture when science has arisen in its full utilitarian majesty, laying claim to be the only valid form of knowledge. In contrast, the Platonic revelatory moment cannot be summoned up at will, it is not biddable; the quotidian vessel suddenly fills up with a revealed meaning that is beyond analysis. As such it is profoundly unscientific: unrepeatable, unverifiable, personal and unshareable. We note in this respect how Chandos deliberately avoids the place where one of his revelatory moments took place: the aura of wonder would still be there and would be damaged by analytic probing or attempts at repetition. His attempt to command it would destroy it.

In putting forward this view of things at the beginning of the 20th century Hofmannsthal was not alone: we may even speak of a Zeitgeist: James Joyce and his 'epiphanies' in Dubliners (1914) and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) and the multilayered metaphorical realities of Ulysses (1922) and Finnegans Wake (1939); Ezra Pound and his metamorphoses, magic and the divine manifestations that burst through into the everyday world in his Cantos (1917-69); T. S. Eliot and W. B. Yeats and so on and so on.

Plato would have understood Hofmannsthal's Chandos perfectly, as would Vincent van Gogh, speechless in the world of wordless everyday objects that suddenly stand out from the quotidian. Words fail in that moment – pick up a brush:

Vincent van Gogh, Shoes, 1886, Paris. Image: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh, Shoes, 1888. Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Vincent van Gogh, Pollard Willow, 1882, The Hague. Image: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield with Crows, 1890, Auvers-sur-Oise. Image: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

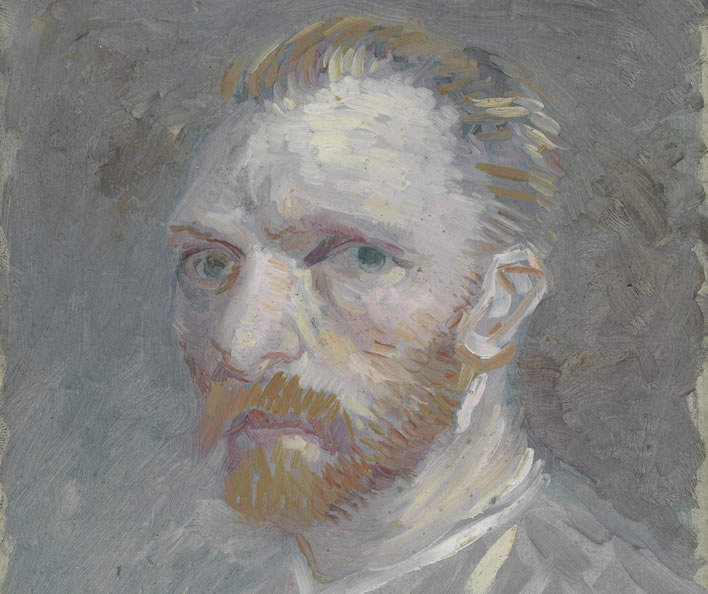

Vincent van Gogh: wonders beyond reason

And the madman – the maniac – is himself an object in the quotidian world of things. He looks in the mirror and sees an object for which words are no longer sufficient. Without pause for Aristotelian ratiocination he picks up a brush and captures on a piece of cardboard in a few minutes that moment of perception, that message from the gods that mere analytic rationality cannot comprehend:

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1887, Paris. Image: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Back home

With visual guidance from Vincent van Gogh we have looked at just a few cases of that act of stepping out of everyday reality which some call madness.

We could now extend our wanderings with a tour through the three Hs: Hegel, Husserl and Heidegger, but that would be a long and challenging tour and we are already weary, ready to return home before night falls when we will all be both physically and mentally umnachtet 'surrounded by night'.

Let's leave a visit to Hölderlin's Bacchic night for another occasion. Iris probably had a hand in this, for that night defeats mortal comprehension. Here's a glimpse:

But the night has also to grant us

that in the hesitant spell,

that in the darkness,

there are some things we can comprehend,

grant us the forgetfulness and the divine drunkenness,

grant us the flowing word, the word that is like lovers,

grant us,

sleepless and full of wine and audacious life,

sacred memories, too,

that we can stay awake through the night.[7]

Turning our backs on this rocky path, Plato, who started us off on this tour, can lead us safely and happily back to the point where we set off:

the greatest of blessings come to us through madness, when it is sent as a gift of the gods.

…

And a third kind of possession and madness comes from the Muses. This takes hold upon a gentle and pure soul, arouses it and inspires it to songs and other poetry, and thus by adorning countless deeds of the ancients educates later generations. But he who without the divine madness comes to the doors of the Muses, confident that he will be a good poet by art, meets with no success, and the poetry of the sane man vanishes into nothingness before that of the inspired madmen.[8]

It's fun being a Platonist.

References

- ^ Plato, Theaetetus 155d, Greek,English.

- ^ Aristotle, Metaphysics 982b, Greek,English.

-

^

Hölderlin, Friedrich. 'Brod und Wein' in Sämtliche Werke. 6 Bände, Band 2, Stuttgart 1953, S. 93-99. Excerpt: lines 13-18. Translation: FoS. Online. [Our text incorporate emendations from Groddeck, 2012].

Jetzt auch kommet ein Wehn und regt die Gipfel des Hains auf,

Sieh! und das Ebenbild unserer Erde, der Mond,

Kommet geheim nun auch; die Schwärmerische, die Nacht kommt,

Voll mit Sternen und wohl wenig bekümmert um uns,

Glänzt die Erstaunende dort, die Fremdlingin unter den Menschen,

Über Gebirgeshöhn traurig und prächtig herauf. - ^ Hamsun, Knut. Pan, trans. W. W. Worster, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1921. Excerpts from Chapter IX.

- ^ Hofmannsthal, Hugo von, and Mathias Mayer. 'Ein Brief' in Der Brief des Lord Chandos: Schriften zur Literatur, Kultur und Geschichte. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2007. Universal-Bibliothek 18034. p. 53. Translation: FoS. Online

- ^ Ibid, p. 55f. Translation: FoS. Online

-

^

Hölderlin, Friedrich. 'Brod und Wein', lines 31-36. Translation: FoS.

Aber sie muß uns auch, daß in der zaudernden Weile,

Daß im Finstern für uns einiges Haltbare sei,

Uns die Vergessenheit und das Heiligtrunkene gönnen,

Gönnen das strömende Wort, das, wie die Liebenden, sei,

Schlummerlos, und vollern Pokal und kühneres Leben,

Heilig Gedächtnis auch, wachend zu bleiben bei Nacht. - ^ Plato, Phaedrus 244a-245a, Greek,English.

Update 25.06.2016

I, drunken fool, posted the document without its concluding section – hereby corrected. Moral: keep off the Bacchic mania when you are operating a computer.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!