Classic books

Richard Law, UTC 2016-07-16 10:45

The well of unknowing

'This work is in the tradition of The Catcher in the Rye'.

Here we go again. For The Catcher in the Rye is just another of those 'classic books' which I have never read. It is true that on a few occasions during the course of the last half century I may have thought of reading it, just as I may have thought of reading each of the other books in that mountainous pile of unread classics – but it just never happened. I know in my heart that I will never read it either, for 'to everything there is a season' and my season for reading The Catcher in the Rye passed long ago. I am rapidly running out of years for all this catch-up reading of classic books.

Classic book shame can strike at any time. Sensible adults may suddenly start talking to me about the Winnie the Pooh books and honey and 'pooh sticks', or the Peter Rabbit books by someone whose name escapes me for the moment – it will come to me soon – or The Railway Children: all just one blank after another for me. More disturbing for me is the assumption that I must have read all these works, because… well, everyone has. What gap in the life of my mind needs to be filled by reading any of these? And who was Mrs Tiggywinkle and why do I need to know about her?

My childhood was filled with the Biggles books, but apparently they are no longer regarded as classics – indeed, if you have read them it is best to keep that fact to yourself nowadays.

Wikipedia: best avoided

No matter how jarred you are by a sudden attack of classic book shame, do not buy a copy of the classic in question: you will almost never get round to reading it. The book will just sit there next to all the other things you haven't read and end up, after your demise, in a second-hand bookshop marked 'new condition' or 'faded spine'.

Nor should you under any circumstances look up your neglected classic on online sites such as Wikipedia. In the case of The Catcher in the Rye you will be told that

The novel was included on Time's 2005 list of the 100 best English-language novels written since 1923 and it was named by Modern Library and its readers as one of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. In 2003, it was listed at #15 on the BBC's survey The Big Read.

And you, slothful worm, have never even read it! Although, come to think of it, I have never come across a Wikipedia entry for a classic book that says: 'reading this book is a waste of time', which is certainly the case for quite a number of the classic books I have read.

Even if you have never read one of these classic books you will as a minimum be expected to name the author and have at least a rough idea of the year of its publication. [J. D. Salinger in the 1950s, since you ask.]

The classic-book mountain

So it can be really annoying to be reminded by the likes of Wikipedia that a book is one of the steps in that long, winding and tedious road up the classic book mountain, the mountain of all those books that 'everyone' has read or is expected to have read.

The best way of avoiding classic shame is, of course, complete ignorance – it really is bliss. If you have never even heard of The Catcher in the Rye you will not be upset when anyone mentions it. For you there is no mountain of classic books on your horizon. You can even accuse the person mentioning the book of mannered obscurity – of being a 'pseud' as it used to be called.

Anyway, if you have read The Catcher in the Rye and are currently basking in that lovely, warm smug feeling, what about The Imitation of Christ? Emma? Dombey and Son? The Pied Piper of Hamelin? Moby Dick? Don Quixote? The Great Gatsby? Vanity Fair? Endymion? Walden? and so on – you can see the steps up the mountain of classic books ascending into the mist that forever cloaks the summit of this peak. Few have managed the weary trudge to the summit; some have staggered into the mist, never to be seen again; there are happy people have never even put their foot on the bottom step. [The Bible, since you ask.]

Perhaps asking whether you have read a book is unfair; the real issue is whether you know the bite-sized 'brand message' that is attached like a label to each of these books. I have never read The Catcher in the Rye but from what I've heard of its brand message I think it is one of those 'childhood' books such as Cider with Rosie– which I haven't read either – or Lark Rise to Candleford, which I have read (well, nearly all of it) and rather wish I hadn't.

If you remember the brand message and the name of the author of these works, honour would probably be satisfied. It's not difficult: Moby Dick (not read) is something to do with a whale; The Pied Piper (read) is about a musical child-snatcher; Treasure Island (tried, but gave up) is about a one-legged pirate; Don Quixote (read, with patches of tedium) is about some deranged person who charges at windmills and who has a little fat sidekick called Sancho Panza.

As it happens, 2016 is 'Cervantes Year' in Spain, the 400th anniversary of his death. Because so few have actually read the novel the celebrations are reduced to recycling the brand messages: windmills, gaunt men on horses and… well, that's about it.

If I were required to distinguish between the plots of the various Dickens novels I could probably do A Tale of Two Cities (read) and Great Expectations (not read but bluffable) reasonably well but the rest of his stuff is fragmentary and muddled: a page from one could just as well be from any of the others. The plot of A Christmas Carol (not read) would be straightforward, of course, as long as the plot of the book corresponds with the Muppets film.

The four levels of classic-book shame

These are:

- Level 1: Total ignorance. Never heard of the book and therefore also no idea who wrote it. Do not care, either. Mental state: Unclouded happiness.

- Level 2: Heard of the book or the author, but unable to connect the one with the other. Mental state: Slight distress, leading to the avoidance of quiz games.

- Level 3: Can associate book with author. No idea what the book is about. Mental state: Lack of self-esteem, but participation in quiz games can reduce this feeling.

- Level 4: Knows the brand message, possibly an approximation of the year the book was written. Mental state: Confidently deluded.

How to lose friends and influence no one

Go out and buy an unread classic book if it makes you feel better. As we have already noted, you are just wasting money because you will probably never read it. After a glance at the publisher's blurb to get an idea of the brand message put the book on a shelf and forget it, because the one thing you must never, ever do is to succumb to the temptation of reading one of these classic books.

For, when you finally read one of these books, you will realise that the brand message in which you believed so firmly up to now hardly corresponds to the content of the book at all. Lark Rise to Candleford is not just a book about childhood; Don Quixote is not just about a lunatic tilting at windmills; the 'Parable of the Talents' in the Bible has nothing to do with talents in the modern sense of the word.

You thought you were ascending one more step up the mountain towards the heaven of the widely-read. Instead you have slithered downwards towards that special, terrible circle of Hell reserved for people who really have read a classic book: the unloved, the rejected, the socially spurned, writhing in an agony of knowing something better than anyone else. You will go from being confidently deluded like everyone else to being obsessively superior and hated by everyone you meet. Barely a day will pass without you correcting someone. People can warm to a dolt, but the knowledgeable are never forgiven.

Take Don Quixote, for example. Under any pretext you will feel driven to explain the work: the importance of the second part, the longest part of the book, which few read. Its ten chapters contain nothing of windmills.

Those who make it this far in the book find that Spain's 'national book' is no longer set in Castille and written in a Castillian dialect. It has moved to Barcelona, the Catalan capital where Catalan is spoken. Thus modern 'united' Spain finds itself celebrating a novel which comes from a time when the Castillian and the Catalan regions were more or less equal partners with a more or less autonomous existence. Suddenly all the windmill tilting and the crazed, gaunt man on a horse pursuing the chivalric phantoms of a bygone age are in a much larger context. And you really have to tell everyone about this. You will have also formed a deeply considered opinion on whether to use an anglicised, Castilian or Catalan pronunciation for the title and you will be driven to correct the ignorant fools who misspeak. Even people who were previously well disposed to you will now hate you. Why not just leave it at a gaunt man on old 'Rosinante' (knowing the name of the horse is always a plus), a fat man on a donkey and a few windmills? That is the true way of happiness, but it is not a way that you will be able to hold to: you've read the book and you know.

The Teutonic hell of classic books

We old cynics on this blog are not surprised that the deepest, the darkest and most tortured circle of classic-book hell is reserved for German literature.

The Germans are proud of their thoroughness, their Gründlichkeit, even mocking themselves, albeit proudly, for this defining characteristic of Germanhood.

Throughout my ponderings on the nuisance arising from the idea of must-read classic books in English it never ocurred to me as author to produce a comprehensive list all the classic books in the classic-book mountain, nor to you as reader to expect that I produce one. Would you really read it? Why undertake such a pointless compilation when we both could be drinking something cheering and doing useful things?

In contrast, for a German literary person it is a wonderful thing to do, though it costs the compiler years of relentless scribbling and ends only in wrecked eyesight for both scribbler and reader. What to the Briton is an amorphous pile of stuff to be avoided, to the German is a challenge: a list will be made and then everyone knows what it is that they have to do: read it all!

And the creation of a classic-book mountain is exactly what Germanic culture attempted in the fifty years after World War II. Clever people might see in this labour an attempt to retrieve the glories of German history and culture from the layers of rubble under which they had been buried.

There was a time in the mid-19th century when German culture was almost universally respected. However, by 1945 it no longer passed the sniff test. There is a great paradox here, that the task of rebuilding the literary culture of Germany required exactly the kind of mindless thoroughness, the obsessive drive to completion, the authoritarian habits and the deference to said habits that led to the creation of that rubble in the first place.

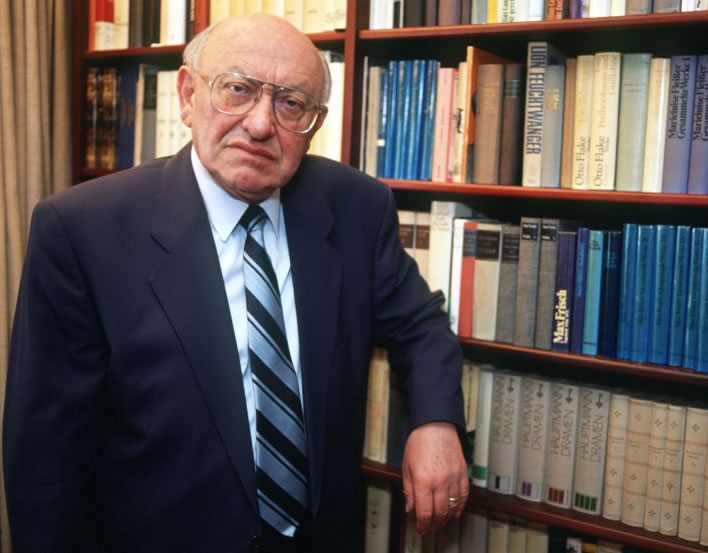

And, paradox upon paradox, it was a Polish Jew who survived the hell of the Warsaw Ghetto who played the largest part in this effort. His authority was so great that he became known as the 'Literature Pope', a figure dispensing infallible doctrinal truth to the faithful. His authority grew and grew: it was clearly fulfilling some deep need among the German cultural masses – 'Here tulips bloom as they are told', as Rupert Brooke put it in Berlin in 1912. Meet Marcel Reich-Ranicki (1920-2013).

The Literature Pope

Marcel Reich-Ranicki (1920-2013): Would you pick an argument about German literature with this man? Me neither.

Reich-Ranicki dispensed authority and certainty. He did that in numberless literary supplements in newspapers, cultural talkshows on television and quite monstrous publishing projects. As a result, despite never having written anything of note himself, from the 70s onwards he was festooned with almost every medal, diploma and award that Germany can offer. He found a market, tapping a deep need in German life for approval and authoritative directions.

If you are prepared to spend enough money you can buy Reich-Ranicki's authoritative collection of all the German literature that in his opinion is worth having: Der Kanon. For your money you get five boxes – yes, boxes:

– Novels: 20 volumes, about 8,200 pages, 150 EUR

– Short stories: 11 volumes, about 5,700 pages, 100 EUR

– Plays: 9 volumes, 43 plays, about 4,300 pages, 100 EUR

– Poetry: 8 volumes, 1,370 poems, about 2,500 pages, 60 EUR

– Essays: 6 volumes, about 4,500 pages, 80 EUR

Only about 25'200 pages to plug through. Possession will cost you 500 EUR, the consumption and digestion of this immense string of Würste the rest of your life, for which process may you have a long one.

Oh, and one more thing: when you have gobbled, digested and excreted that lot you should then acquire Reich-Ranicki's other series, the Frankfurter Anthologie of poetry with commentary, which not only tells you which poems to read but also supplies an authoritative commentary and explanation of what the poem is about from big names in the literary world. Only 33 volumes containing nearly 2,000 poems and explanations to plug through, probably costing another 500 EUR. Work on the series has continued after Reich-Ranicki's death and now includes non-German works – where these have been translated 'acceptably' into German. By the time you have tramped dutifully through Reich-Ranicki's 33 volumes there will be more waiting for your further delectation.

I will spare you the details of Reich-Ranicki's other collections, of which there are many. At this point the German classic-book mountain becomes a strictly German neurosis that should not be probed too deeply by foreigners.

So, if you are German and have about 1,000 EUR to spare you can have the complete German classic-book mountain at home on some (sturdy) bookshelves. An expensive way to prop up loudspeakers.

The Literature Rabbi

Marcel Reich-Ranicki was not just the 'Literature Pope', dispensing infallible literary wisdom to his sheep flock, he was even more the 'Literature Rabbi'. Collecting texts and summaries of texts and commentaries on texts and commentaries on commentaries is a profoundly Jewish habit, a rabbinical habit to be precise.

Reich-Ranicki described his canon as the preservation of culture that mattered, should culture be destroyed, whether by TV, the encroachment of the English language, video games, the Russian hordes – well, pick your threat. He really was attempting to rebuild an authoritive German literary culture out of the Trummerfeld, the rubble, of World War II. His collections are created for a people who are still to this day filled with respect at Bildung, 'educational attainment', that was in large measure also a specifically Jewish aspiration. His codification projects are based on the neurotic foundations of classic-book shame.

There will be birthdays and Christmas Eves when proud parents watch their children opening up a large, gift-wrapped box and savour their cries of surprise at finding therein the 20 volumes of Reich-Ranicki's canon of German novels. There will be tears, some of gratitude.

The classic-book mountain without tears

What German readers really need is some hero (not me) to stagger up Reich-Ranicki's mountains and then bring down the tablets in the form of a slim – very slim – volume containing just the titles, authors and the brand messages we need to know. Goethe, Faust I: clever dick makes pact with the Devil, everything turns out badly; Schiller, The Bell: a bell is made; Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain, young man visits a hospital in the Swiss mountains and catches his death of cold.

With a bit of luck you might come in under twenty pages. All the other thousands upon thousands of pages are just mere detail. Despite this immense service to German culture, it is unlikely that you would get a medal. They probably won't even thank you for it.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!