The Man in Black

Richard Law, UTC 2016-10-17 10:15

The image itself

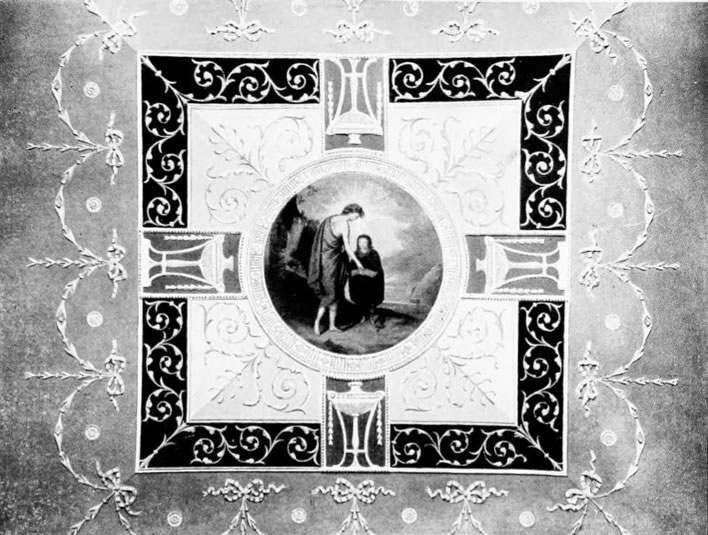

Look at this painting:

Let us consider it free of all distracting metadata: by an unknown artist with no date, free of all comment and opinion.

The painting is executed in muddy tones. Even the flesh tones are muddy. The half-exception is a reddish cap, which looks as though it could blow off or end up in a bowl of soup at any moment. In fairness, it is possible that this muddiness is an artefact of the digitisation process or simply the result of too many postprandial cigars over the centuries.

The proportions of the figure are disconcerting: a tiny head on top of a massively wide chest on top of a tiny, tight-belted waist and tiny hips. The width of the chest is largely an optical illusion arising from the strange pose, the massively dominant sleeve of the left arm and the confused structure of the right arm. The silvery/satiny material of the sleeve is poorly rendered and its clumsy handling would shame most painters, then and now.

The execution of the hands with their over-long fingers is defective; the position of the left hand on the hip is improbable, unnatural even; the separation of the index fingers mannered. The right hand is holding a small document, which seems to be partly within the jerkin and is being either inserted or withdrawn. The nature of the document is not immediately clear to us: it could be a lottery ticket for all we know.

The execution of the subject's right side presents the viewer with many puzzles: the descending and elongated right shoulder – note the misalignment of the scalloped armholes of the jerkin on the left and right shoulders; the huge, weighty and dark balloon of the right sleeve; the odd geometry of the right arm. If a painter is going to mess around with 'mannerist' viewpoints, the perspective has to be right – as here, for example:

Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617), Phaethon Falling, from his series Die Vier Stürzende / The Four Fallers, 1588, based on paintings by Cornelis van Haarlem (1562-1638). Image Musea Brugge. The bits of the Chariot of the Sun that Phaethon had so unwisely taken for a spin can be seen following him down.

The face on the tiny head is unattractive. It is dominated by an extraordinarily oversized, fat nose. The artist should have helped the sitter out in this respect. The eyes are large and staring down at something out of the picture. The expression is undefined: certainly not happy, but not anything else either.

The face and the two hands are three dull highlights gleaming in the pervading dolour. The subject's head takes up less than a quarter of the vertical height, the rest is mostly the black, uninteresting jerkin. Is this a portrait or an image for a clothes catalogue? It is obvious that this was a portrait knocked off on a shoestring budget at the expensive of complexity and skill. The artist was either incompetent or not trying – or both.

What does Mammon think?

How much would you pay for this painting today? Let's say in GBP: £20? £200? I personally wouldn't pay anything. I wouldn't want this disturbingly bad effort on my wall even if it were given to me. Every time I looked at it I would see only its blemishes. Awful.

Let's add a little bit of metadata now. An anonymous 'American collector' paid £30,618,987 for this work. Take some time to restrain anything you may have recently eaten from forming a Willem de Kooning on your computer monitor. Breathe deeply and repeat after me: £30,618,987 – thirty meeelion. How on earth did that happen?

Since the painting itself is incompetent, ugly and worthless, the metadata must be very expensive. If American collectors want to spend that kind of money on dross, well, that's fine, but the British taxpayer is currently being asked to come up with £30m to 'save it for the nation'.

The lucky owner

Let's dig down into the metadata in search of that gold.

We know that the portrait has been in the possession of the Earls of Caledon since 1825. The dynastic founder made a fortune with the East India Company in the late 18th century and rose rapidly on the back of that money to an Earldom of the Irish Peerage in 1797. The family's base is Caledon House, Caledon, a small village in Antrim, Northern Ireland, very close to the border with the Irish Republic.

Here we are:

Caledon House, n.d., Drawing room, Saloon, Boudoir, Boudoir ceiling all taken about 1910. Images: Landed Families. (includes descriptions and family details).

Penury, sort of

The photographs of the interiors of Caledon House from the 1910s display that remarkable lack of taste that only large amounts of money can produce. The founder's money was reinforced by some lucrative marriages over the years, but times seem to have become tough for the Caledons. The current head of the family, Nicholas Alexander, the seventh earl, was divorced from his first wife after six years of childlessness in 1985 (kerching!), his second wife (two children), lasted 11 years: they were divorced in 2000 on the grounds of his serial infidelities (kerching!). He married the third Countess of Caledon in February 2008.

2008, the year of the wedding, was also the year of the great financial crash and the climax of the especially serious financial turmoil across the border in the Rupublic of Ireland. For the landed gentry, possessions are one thing, income is something quite different and much more precarious. The first sign of straightened times for a landed family is obvious: someone from one of the great auction houses is invited to come and rummage around the pile and see what can be flogged off. In Caledon's case the expert was Francis Russell, currently Deputy Chairman of Christie's, the auction house.

We don't know whether Russell, the Italian Old Master specialist at Christie's, was personally rummaging around in Caledon House or was hauled in by an underling, but he asserted that one particular painting, thought up until then to be by Alessandro Allori (1535-1607), was in fact by Jacopo Pontormo (real name Jacopo Carucci) (1494-1557). I have not seen the provenance of the work or the justification of this claim, but that is not the point at the moment: the painting is pretty poor whoever painted it. In effect, Francis Russell changed the artist metadata from Alessandro Allori to Jacopo Pontormo and struck paydirt for its owner and for Christie's.

Russell's discovery was loaned to the National Gallery and got a front cover and a short notice in the The Burlingtom Magazine in October 2008, both excellent ways of dangling the new find under the noses of the art collectors of the world to let them have a good sniff. Russell and his employer Christie's did not reveal that the owner is Caledon, an example of those strange secretive behaviours that are regarded as normal in the murky pond in which the slithering percentage-commission predators of the art world wriggle and turn. The painting was lent to the National Gallery with an oral agreement that three month's notice would be given before it was put up for sale.

Going cheap

But Caledon seemingly needed the money fast. That oral agreement was broken and the painting of the anonymous owner was sold to an anonymous American collector for £30,618,987. Another sign of hasty desperation is that the inheritance tax on the transaction, which was at a very high rate we are told, was paid in full straight away. Those in the know assume that this technique was used to try and shift the painting before its export could be barred.

But barred it was. Possibly the breach of faith with the National Gallery by the seller was the provocation. Judging from Caledon's numerous breaches of marital promises we should not really be surprised at his behaviour.

The UK government placed an export bar on the painting in 2015 'to provide an opportunity to save it for the nation'. It is currently waiting for someone to come up with £30,618,987 to match the price paid by the 'anonymous' US collector. Since then the Government – drowning in debt – has come up with a £19m 'grant' towards the purchase of the work.

Working in round figures we can guess that Caledon got around £10m from the sale, the UK government got around £19m in tax and Christie's around £1m (I have no idea what the commission on a £30m sale is).

If Britain wants to 'save' the painting, £30m has to go back to the American buyer. This means that the Government has to give Caledon his £20m tax back, he adds his £10m sale income to that and gives it all to the American. The government then gives Caledon £10m for the painting and refrains from claiming tax on that sum. Everyone comes out whole and Christie's loses nothing. Auction houses and bookmakers never lose, only the taxpayer, who couldn't care less about Pontormo and his 'masterpiece'.

The Government is currently calling the refund of the £19m tax payment a 'grant' – whatever, the taxpayer pays in the end.

Why bother?

Leaving aside our own judgement that the painting is not worth the canvas on which it was painted – a slightly extreme view we admit – the current situation seems relatively satisfactory: Some American has this inferior painting and has paid £30m for the pleasure of owning it; Caledon has £10m to keep the dynasty afloat for a few more years, the UK Treasury has received £20m. Christie's are happy whatever happens.

But why should anyone care who owns this painting and where it is hung?

Make a nice high-resolution image freely available on the internet, for example as part of the Google Art Project or Art Project Gigapixels. After that it doesn't matter whether it is kept in some billionaire's bunker somewhere in the world, or displayed in some entrance-fee bunker somewhere in the world (a.k.a. an art gallery) or displayed in some exclusively taxpayer-funded bunker somewhere in the world (a.k.a. the National Gallery, London).

True, some paintings have attained an 'iconic' status in the common mind and as such their physical presence is required. There seems to be an unending source of people prepared to wait in long queues at the Louvre in Paris, pay an exorbitant entrance fee (€15) in order to stand in reverence for a minute or two in a huge crowd in front of the Mona Lisa. The small painting is so heavily protected behind thick armoured glass and the viewing distance is so great (c. 5 metres from the front rail) that it is certain that the assembled worshippers see much less than they would in a reproduction of the painting in the average coffee-table book. The piece and the worship of it has exactly the same projected glamour and sanctity as the Turin Shroud or the left toenail of Saint Wotsisname paraded around once a year in a monstrance.

In contrast, Pontormo's portrait is not one of these iconic works, not by a long chalk. We managed to live without the painting quite well for two hundred years – its 'rediscovery' has changed nothing. It wasn't really rediscovered at all: it was re-attributed as the work of a different painter. It is, however, the same work that has been mouldering in deserved anonymity in Caledon House for the last two centuries. Nothing has really changed: for two centuries the Caledon family and their guests have thought the portrait quite unremarkable, just part of the other accumulated junk they have lying around. Since 2008, however, the 'experts' kneel in trembling homage before it and require £30m from the public purse to 'save' it.

The identity of the figure in the portrait is a guess. Most of the imputed context is also guesswork. It is an interesting insight into the muddy pond that is the artworld that when Russell got the painting into the Burlington Magazine for the collectors of the world to view he originally called it A portrait of a young man in black, which is a gloomily accurate reflection of the painting. Since that time it has become A Young Man in a Red Cap or even more beguilingly A Boy in a Red Cap, presumably just in case we fail to miss the only semi-interesting feature of the painting.

If the painting ends up in the National Gallery can we assume that the visitor numbers will not be increased in the slightest by the presence of this work? Absolutely. Since entrance to the National Gallery is free the number of visitors is not an economic factor anyway.

The official mind

In 2015, the then Culture Minister, that odious and ineffectual careerist Ed Vaizey (now back on the backbenches where he belongs), asserted: 'I want to help make sure the UK doesn’t let it go now' and hoped that 'a buyer comes forward to save this striking painting for the UK public to enjoy.'

The hypnotic snake-eyes of the British art world have clearly got to Sir Hayden Phillips, a retired career civil servant who is now the Chairman of the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (RCEWA), administered by Arts Council England. His faculties wizened and atrophied by decades of minute-writing tedium, he dissolves on cue into embarrassing hyperbole:

As the lay Chairman of a Committee of experts all I would say is that this picture is stunning. It bowled me over by its striking beauty. Let’s try to keep it so more people like me in the UK can be bowled over too.

Writing in the Guardian, Jonathan Jones is another worshipper – careless of price as long as someone else is paying. After many hasty and specious assertions masquerading as analysis he concludes:

'Portrait of a Man in a Red Cap' is a work of immense historical weight that is worth every penny the National Gallery wants to spend.

Well, this is the Guardian, isn't it?

The FoS solution

If some private collector loves this work enough to pay £30m for it, that's fine. Just take a high resolution image, put it on the web and let some rich person cart off the original. Then everyone can see it whether they are in London, Paris, Florence or Duluth, Minnesota. I'm not sure it's even worth doing the replication – there is nothing in the painting that deserves high-resolution inspection: The cap? The deformed hands? The oversize conk? There are many more paintings in the world that deserve this treatment before we get round to the present specimen.

With our solution the Earl of Caledon is happy, the UK Treasury is happy, the half-a-dozen people in the world who care about Pontormo have free access to a detailed image. And, above all, the taxpayer is happy – wildly, deliriously happy: after all, that money could be used to subsidise a wind farm. What's not to like?

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!