Bible studies

Richard Law, UTC 2016-10-02 11:04 Updated on UTC 2016-10-25

Those bewildered people who maintain as an article of faith the literal truth of the Bible are, in fact, the book's worst enemies. The immense strength of the Bible lies in its uncertainties, particularly its scope for interpretation and commentary. We would expect nothing else from a Jewish book.

Atheists such as we can dismiss the book – leaving aside its historical record of the tribe – as a collection of fairy stories, but we cannot dispute its power to provoke thought. Encountering the Bible in school without forced learning by rote – such as that required by another religious book we might mention – is an educational act. It does not supply answers, it supplies questions.

The fact that the Bible is a collection of very different texts from very different authors adds to its value: it is not a religious monologue or rant – unlike another religious book we might mention – it is a library of different books. Can we use the now worn-out word 'diversity'?

On many occasions the biblical texts are profoundly allegorical, their language, too, deeply metaphorical. There is no definitive meaning to be had: what meaning we readers extract says more about us than the text we are reading. The process of extracting meaning is in itself a fundamentally religious process, full of reflection and self-analysis. In this the literalists completely miss the point.

Those desiccated people who want to suppress all pictorial or literary commentary on religious texts – such as the readers of another religious book we might mention – miss the leverage that is derived from artistic intepretation, which is ultimately a metaphoric act upon these extremely metaphoric texts. Such works have all the validity of scriptural commentary. More than that, they 'bring the soul of man to God' as Yeats put it.

We looked critically at the accepted interpretations of two biblical stories nearly a year ago: Abraham's (near) sacrifice of Isaac [Genesis 22:1-18] and the story of Doubting Thomas [John 20:24-29].

Caravaggio expressed them so:

Caravaggio: The Sacrifice of Isaac [1601-02], Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

Caravaggio: The Incredulity of Saint Thomas [1601-02], Schloss Sanssouci, Potsdam

Shortly afterwards we invoked the Book of Job against the faithless Archbishop of Canterbury, no less.

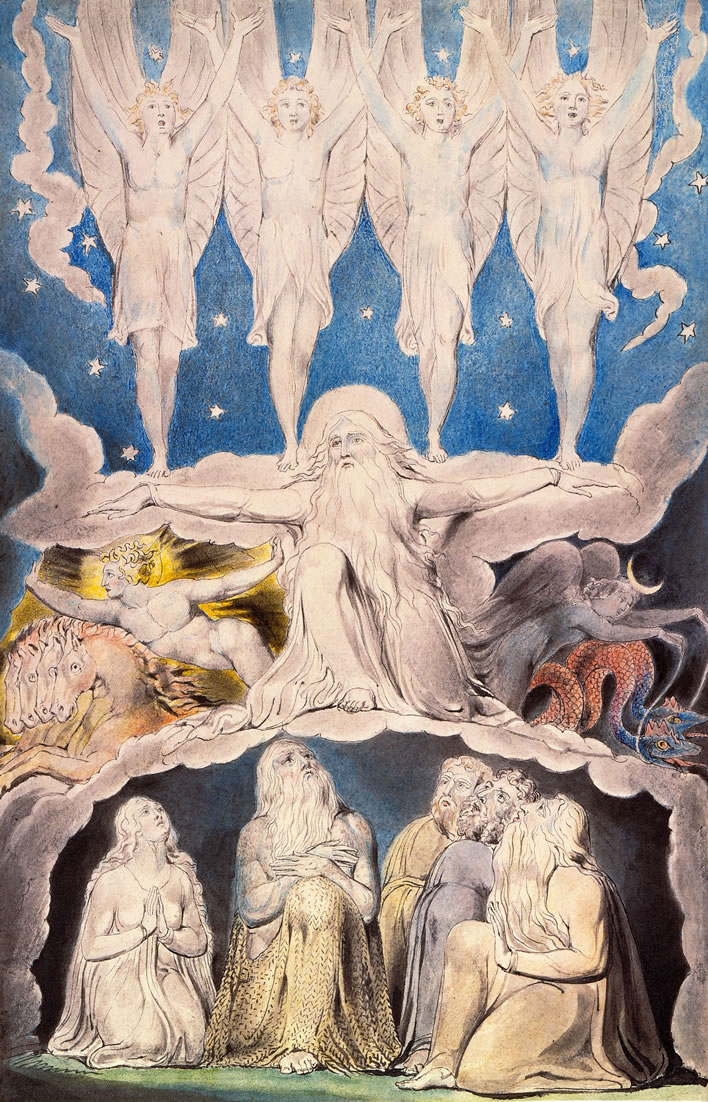

William Blake (1757–1827), Book of Job, no. 14, 'When the Morning Stars Sang Together', c. 1805, The Morgan Library, New York.

When the stars threw down their spears / And water'd heaven with their tears: / Did he smile his work to see? / Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

William Blake, Songs of Experience, 'The Tyger', 1794.

That book alone is a mighty sword of burning gold against the trite, the glib, the bigoted and the over-confident who infest public life these days, one which we atheists are happy to wield, even if Christians won't – and while the other lot are learning their pre- and pro-scriptive lines, hoping their powers of memorisation will get them to heaven.

7– So went Satan forth from the presence of the Lord, and smote Job with sore boils from the sole of his foot unto his crown.

8– And he took him a potsherd to scrape himself withal; and he sat down among the ashes.

9– Then said his wife unto him, Dost thou still retain thine integrity? curse God, and die.

10– But he said unto her, Thou speakest as one of the foolish women speaketh. What? shall we receive good at the hand of God, and shall we not receive evil? In all this did not Job sin with his lips.

The Bible, Book of Job, chapter 2, King James' Version.

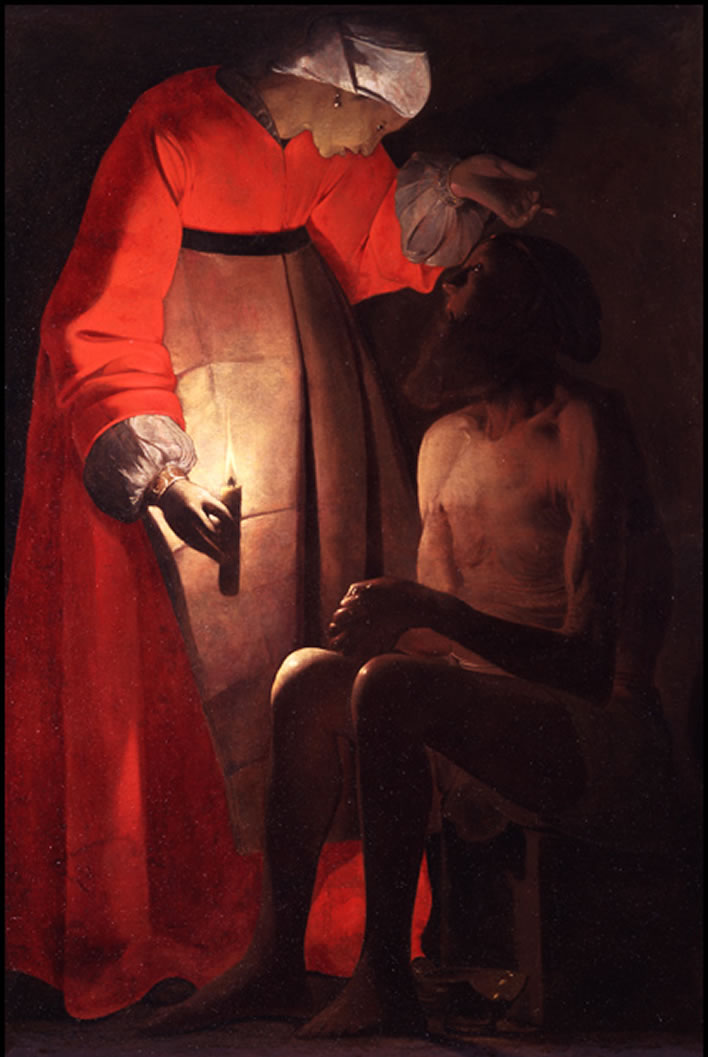

Or, as Georges de La Tour put it:

Georges de La Tour, Job raillé par sa femme 'Job Mocked by his Wife', 1630s. Image: Musée Départemental des Vosges, Épinal. We apologise for the poor resolution of our image of this wonderful painting, but the museum – kept afloat on public money – would prefer that you travel to Épinal and pay them €10 for a fleeting glimpse. Where are the painful boils when they are needed?

Update 25.10.2016

Looking once more at Georges de La Tour's magnificent painting, Joseph Roth's equally magnificent novel Job, the story of a simple man came to mind. Both are metaphors of the one biblical metaphor and should be considered side-by-side.

The story so far: Mendel Singer – the 'Job' of the book – teaches the young children of a small Ukrainian village Hebrew and the Torah. The story begins around 1900. Mendel Singer's work (he is a melamed) is low-status and his income meagre. He is a representative of the numberless poor who have no power over their destiny. Nevertheless, he has a good marriage, he loves his wife Deborah and they have a daughter and two sons. When Menuchim, the fourth child, is born he appears to be severely mentally handicapped, almost sub-human. Deborah is saving money as best she can so that she can take him to a 'miracle-worker' Rabbi.

'What are you trying to do, Deborah?', said Mendel Singer, 'the poor are powerless, God does not throw stones of gold down from Heaven, they do not win the lottery and they must bear their lot with humility. To the one is given and from the other is taken away. I don't know why he is punishing us, first with the sickly Menuchim and now with the healthy children. Ah, when the poor man has sinned he suffers and when he is ill he suffers. One has to bear one's fate! Let the sons join the army, they will not come to harm! Against the will of Heaven we are powerless. "He is the source of the thunder and lightning, he arches himself across all the Earth, one cannot flee him" - so it is written.'

But Deborah, her hand on her hip above the bunch of rusty keys, answered him: 'God helps those who help themselves', so it is written, Mendel! You always know the wrong verses by heart. Thousands of verses have been written and you memorise the most pointless ones! You have become so stupid because you teach children! You give them a little bit of understanding and they leave behind all their stupidity with you. A teacher, Mendel! That's what you are, a teacher!

[Translation ©FoS.] For those who read German the original is here: astonishingly it is better than our English – how can that be?

»Was willst du, Deborah« – sagte Mendel Singer – »die Armen sind ohnmächtig, Gott wirft ihnen keine goldenen Steine vom Himmel, in der Lotterie gewinnen sie nicht, und ihr Los müssen sie in Ergebenheit tragen. Dem einen gibt Er und dem andern nimmt Er. Ich weiß nicht, wofür Er uns straft, zuerst mit dem kranken Menuchim und jetzt mit den gesunden Kindern. Ach, dem Armen geht es schlecht, wenn er gesündigt hat, und wenn er krank ist, geht es ihm schlecht. Man soll sein Schicksal tragen! Laß die Söhne einrücken, sie werden nicht verkommen! Gegen den Willen des Himmels gibt es keine Gewalt. >Von ihm donnert es und blitzt es, er wölbt sich über die ganze Erde, vor ihm kann man nicht davonlaufen< – so steht es geschrieben.«

Deborah aber antwortete, die Hand in die Hüfte gestemmt, über den Bund rostiger Schlüssel: »Der Mensch muß sich zu helfen suchen, und Gott wird ihm helfen. So steht es geschrieben, Mendel! Immer weißt Du die falschen Sätze auswendig. Viele tausend Sätze sind geschrieben worden, die überflüssigen merkst du Dir alle! Du bist so töricht geworden, weil du Kinder unterrichtest! Du gibst ihnen dein bißchen Verstand, und sie lassen bei dir ihre ganze Dummheit. Ein Lehrer bist du, Mendel, ein Lehrer!«

Roth, Joseph, and Wolfgang Pütz. Hiob: Roman eines einfachen Mannes. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2013. p. 38f.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!