Will the real Schubert please stand up?

Richard Law, UTC 2017-02-13 10:57 Updated on UTC 2025-01-19

Whenever on this blog we write about some biographical aspect of Schubert we always irritate our readers by repeating our moth-eaten old motto: 'History abhors a vacuum'.

We do this because so much of the serious biographer's time is spent scraping off the fantastical accretions of the Schubert industry that have been used to fill up the many missing bits in the composer's biography. Before too long one scribbler's guess becomes another scribbler's unshakeable truth.

Last year's presidential campaign in the USA did not invent 'post-fact', 'post-truth' or 'fake news' – the Schubert industry has been employing them for the last two centuries.

Oh, while we are at it, we may as well get our other motto out of the way: 'Nothing is ever as it seems'.

Surprisingly, one of the most annoyingly fertile areas for biographical fantasy is Schubert's image. We are fortunate that Schubert's circles contained a number of artists – Kupelwieser and Schwind, for example – and they visually documented the underfunded composer quite well.

Back to basics

– What did Franz Schubert look like?

– He looked like this:

Image of a cast from a death or life mask of Schubert. The image is taken from a postcard printed for the centenary of Schubert's death in 1928.

Well, sort of. This is his death mask – that is, some people think it is his death mask, in which case it was made on or after 3 pm on 19 November 1828. In which case, too, this is an accurate representation of what Schubert looked like at the age of 31.

Some others think it is a life mask, in which case we don't have much idea of its date. It is certainly not the young Schubert, that much is clear. There is one great argument in favour of the life mask hypothesis: the healthy fullness of the features. Schubert's terminal illness lasted about a fortnight in total and for most of that time he could not eat and would have become severely dehydrated. The cheeks are well-filled and show no trace of such sufferings. However, unlike many people at the time, Schubert had a remarkably complete set of fine teeth – we know this from the exhumation of his body in 1863. This might explain why his cheeks were not the sunken hollows that characterise so many death masks.

To be completely accurate, it is not a death or life mask, it is the cast impression of one. The mask itself is a concave mould that is used to create a convex impression. As far as I know the original mask no longer exists or has never been found. There is a financial incentive for a sculptor to destroy a mask once a cast has been made. A number of impressions, of variable quality, have turned up in the murky world of Viennese art dealers. Some representations of Schubert[1] seem to have used the mask as a source, or masks made from other casts.

Whatever. It doesn't really matter. The image corresponds to most contemporary descriptions of the composer's appearance and to several credible representations of him. We note the blockish proportions of the head, the stubby nose, the curly hair and the trademark dimple on the chin. We can say with confidence that we are looking at the face of Franz Schubert in this cast, the face we also see here:

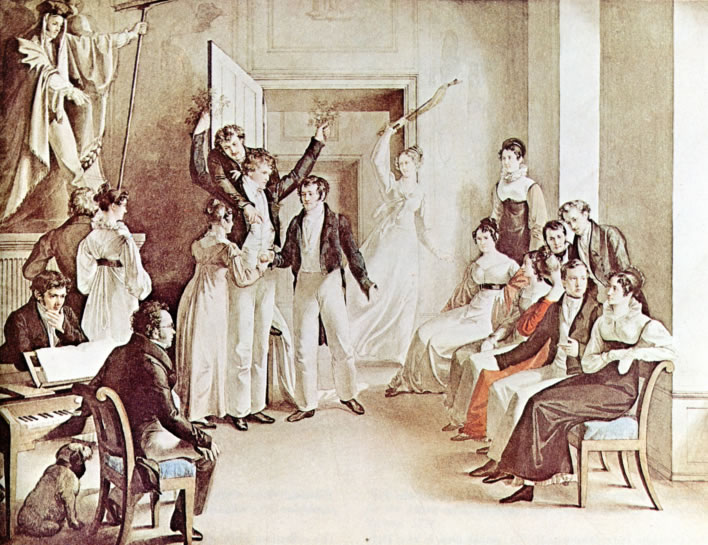

A detail from Moritz von Schwind's homage to a Schubertiade showing Schubert at the piano. This was drawn in 1868, 40 years after Schubert had died, and is therefore not a portrait of any particular event but more of a group portrait of the people in Schubert's life.

Moritz von Schwind's drawings of Schubert, particularly in the famous 'Schubertiade' illustration – a work of imagination 40 years after the fact, albeit a good one – shows the adult Schubert in a way we recognise from the mask: the square head, the stub nose, the chin dimple, the thick neck and the trademark curly hair.

Oh, just a minute though. It looks as though all those years after Schubert's death Schwind may have used a cast from the mask to inform his own representation of Schubert.[2] Our argument is then tautological, but its force is not reduced. Schwind had known Schubert intimately over much of the composer's adult life. His use of the cast is actually evidence that supports the accuracy of the likeness.

For our standard image of Schubert on this blog we use Friedrich Lieder's 1827 sketch of Schubert[3], largely because it is obviously not cosmetically manipulated. We recognise in the sketch all the facial features that we see in the death-mask and in Schwind's representation of Schubert. The head is slightly less square, but for a sketch it is remarkably lively and accurate. Even if the artist and subject were not clear, we would look at it and say without hesitation: Schubert!

Friedrich Lieder's 1827 sketch of Schubert: spontaneous, without cosmetic improvements. The fate of this image is tediously Schubertian. It passed unseen by the world through a number of private collections until it briefly surfaced in the mid-1990s, then once more disappeared. One day, like Gollum's precioussss, it will pop up briefly in some auction house or other before disappearing once more.

Portraits

There is no doubt that the 'official' portraitists 'improved' Schubert in the way that Lieder did not. That was, after all, their job. We find him slimmed down, the pot belly has vanished, the squat face elongated, the stubby nose made noble. Portrait painters would routinely heighten the foreheads of their sitters as a sign of intellect. That pot-belly we see in Schober's vicious caricature, in which the pot-belly is perhaps exaggerated but was clearly not an invention. Schubert liked his food, his wine and his beer.

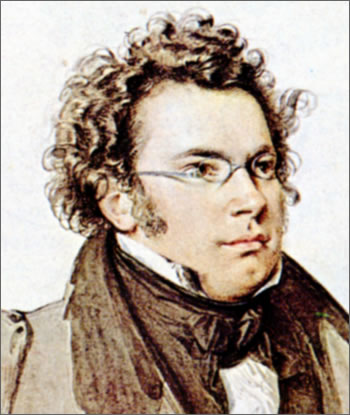

The most famous and well-documented portrait is a watercolour done by August Rieder in 1825:

Wilhelm August Rieder (1796-1880), painted Schubert from the life in a lithograph, a sepia drawing and a renowned watercolour in 1825.

Rieder's watercolour has been taken as a model by a large number of artists in different media. You will come across many derivatives of this image or its details.

Rieder's cosmetic improvements to his sitter's appearance are what you might expect from a skilled portrait painter. The relaxed pose reflects Schubert's relaxed personality – he and his circle of friends disliked what they called the 'stiff people' – but allows Rieder to stretch the short and dumpy composer's body to give an impression of stature. The head is correspondingly less massive, certainly less blockish and has been gently narrowed and lengthened.

Rieder's portraits met with the approval of some who knew Schubert well – Schubert, too, since both he and Rieder signed the sepia and the watercolour versions. But, reading between the lines we are made aware of the deficits and difficulties of portrait painting. In 1858 Leopold Sonnleithner, a friend of Schubert during his adult years, discussed Rieder's representation and Schubert's appearance:

[Rieder's] lithograph portrait of Schubert is the closest likeness. However, the body is too heavy and broad. The large plaster bust [based on the mask] is very accurate, especially in the lines of the mouth.

Schubert was shorter than average, had a round, fat face, a short neck, a not very high forehead and full brown, naturally curly hair. His back and shoulders were rounded, the arms and hands pudgy with stubby fingers. The eyes, when I am not mistaken, were grey-blue. The eyebrows were bushy, the nose short and wide, the lips thick, the face slightly negroid. The skin was blondish rather than brunette, but with a tendency to develop small, darker coloured rashes. The head was set deep onto the shoulders and tilted forwards. Schubert always wore spectacles.

At rest the facial expression was more stupid than intelligent, morose rather than cheerful. One would have assumed that he was an Austrian or more possibly a Bavarian farmer. […] He only became animated among close friends, when drinking wine or beer. Even in these situations he never laughed aloud but just gave a muffled chuckle. Shy and quiet, particularly in the elegant circles in which he appeared as a courtesy in order to accompany his songs. During the performance his facial expression was extremely serious; afterwards he retreated to a side-room as soon as he was finished. […]

He attended house balls in initmate family circles. At these he never danced but was always prepared to seat himself at the piano and improvise the most beautiful walzes for hours. Those he liked he repeated, in order to remember them so that he could write them down later.

Deutsch, Otto Erich, ed. Schubert: Die Erinnerungen Seiner Freunde, Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1997, p. 141. Translation ©FoS.

Joseph von Spaun also took up the theme of Schubert's appearance in a response to the first published biography of Schubert by Heinrich Kreißle von Hellborn (1865):

Schubert has never been properly represented, either in appearance or character. His face is reproduced as almost ugly, negroid, an appearance to which anyone who knew him would object. The portrait painted and etched by Rieder is an extremely good likeness. Just a glance at it will tell you whether the face was ugly and negroid.

On the other hand, one cannot say that Schubert was handsome. He was, however, well-formed and when he spoke with friendship or smiled, his facial features were full of charm. When he worked, filled with enthusiasm and glowing with zeal, his features became exalted and almost beautiful.

As far as his body is concerned, after reading the biography one would imagine him to have been a fat lump. This is completely wrong. Schubert had a solid, squat body, but of fat or of a pot-belly there was no trace. His younger friend Moritz von Schwind exceeded him in circumference even then.

Ibid, p. 416. Translation ©FoS.

We cynical blog writers can only note that in these two accounts each affirmation of the accuracy of Rieder's portrait is followed in short order by statements about Schubert's appearance that contradict that representation.

Two further contemporaneous illustrations of Schubert were produced by Josef Teltscher:[4]

Josef Eduard Teltscher (1801-1837), lithograph, 1826.

Josef Eduard Teltscher, Schubert (detail) from a lithograph after his 1827 color drawing showing Jenger, Hüttenbrenner und Schubert.

Teltscher has taken the squareness from Schubert's head and rounded off his forehead – not quite the accuracy of the mask, but not far away. The emphasis that Teltscher has given to Schubert's lips calls Sonnleithner's remarks to mind: 'the lips thick, the face slightly negroid' and Spaun's rejection: 'his face is reproduced as almost ugly, negroid'. Were the two thinking of Teltscher's portraits?

In contrast, the 1827 portrait now known to be by the obscure painter Anton Depauly[5] pulls out all the stops of cosmetic refinement in portraiture. This is a painter earning his money:

Anton Felix Depauly (1798-1866), 'Schubert without Spectacles', oil painting, c. 1826-1828. The painting was until recently[4] incorrectly attributed to Joseph Mähler.

Depauly is such a master of the portrait painter's black arts that it is not easy to identify what he has done to turn Schubert into a handsome young man. Perhaps leaving off the trademark spectacles is the biggest shock. The dimple is there, the curly hair, but we are clearly at the limits of a faithful representation of Schubert – certainly in comparison with the death/life mask.

Finally, we return to August Rieder. 47 years after Schubert's death he produced an oil painting based on his earlier watercolour:

Wilhelm August Rieder, portrait of Schubert, oil, 1875.

A detail from Rieder's 1825 watercolour of Schubert, showing how closely the oil painting of the head followed the watercolour, every hair in place.

By the time that Rieder was commissioned to do this oil-painting the dead composer had started to become famous and thus valuable. Heinrich Kreißle von Hellborn's biography of Schubert had appeared ten years before and Schumann, Liszt and Brahms had propagandised his music. About a half-century after his death Schubert had become, to put it brutally, worth the paint. In contrast, during his life, Schubert was not rich and barely known outside Vienna. Pencil, chalk, ink and watercolour on paper were quick and cheap: the only realistic media for such a sitter.

Imposters

Now that Schubert is famous and marketable the need for images of him, particularly as a young man, grows by the year. Every 'Schubert' around the world, whether in Austria or the USA, wants somehow to trace his or her descent back to him, our childless composer. The fact is that the lack of portraits from his early years is an outrage that requires a solution. Portraits must be found.

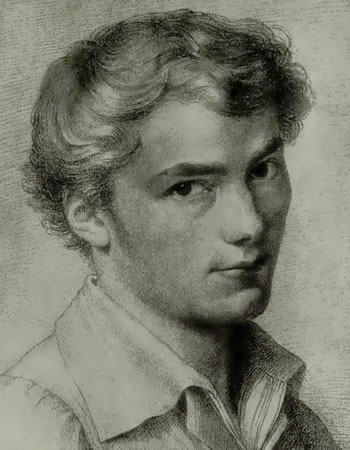

Let's start with this one of the 'young Schubert':

Supposed portrait of Franz Schubert as a 17 year-old. Unsigned. Undated. Artist unknown.

You can choose your attribution for this portrait. Some [e.g. Hilmar, Schubert, 1997] say that it is a drawing done by Franz von Schober in 1814. Schober did not meet Schubert until 1815. Some [Ausstellung, 1978] say that it was drawn by Moritz von Schwind, at that time a ten-year-old who would not meet Schubert for another seven years. Others say it is by Leopold Kupelwieser, who does not seem to have got to know Schubert before 1820.

Enough. It is sufficient for us to state, after all we have discussed so far in this piece, that this cannot possibly be an image of Schubert, or if it is a portrait of Schubert, it is a very bad one. It gives us no idea of his youthful appearance.

Imagining this beanstalk as the young form of the chubby little composer is difficult enough, but one look at the elongated face, the very pronounced nose, the bulging eyes, the featureless lips and misplaced ear should make our minds up on the spot. The mop of hair may give us pause for thought, but it is not really anything like Schubert's tighter curls. The basic problem is that the image is completely generic: eyes, nose, lips, chin – it could be anybody. There is nothing here that says: Schubert!

There is no developmental process in human biology that can take us from this youth through the intermediate stops to the death-mask. If you are putting together a biography of Schubert and the early life is a bit text-heavy, there is no point reproducing this image to bring a bit of life to a page. This person is not Schubert.

Then we have this:

Dr Karl Joseph von Hartmann (1793-1876), chalk drawing by Leopold Kupelwieser[?], 1821?. Kupelwieser created a series of head and shoulder portraits of members of the circle of friends around Schubert in the early 1820s. The image of Hartmann could plausibly be part of that series.

Using the common sense we applied to the previous representation we come quickly to the conclusion that this cannot be Schubert, either. A no-brainer as we say these days. There are no features in common with the death/life mask.

In 2014 the musicologist Michael Lorenz let off steam about the repeated use of this image to represent Schubert. He demonstrated in convincing detail that it is not a portrait of the composer but of a Dr Karl Joseph von Hartmann, who was indeed one of Schubert's circle of friends. He was introduced into the circle by Franz von Schober, who had known him during their time as pupils of the Kremsmünster school.

Hartmann has not only achieved lasting pictorial fame by being touted as Franz Schubert. Kupelwieser also incorporated him in the famous scene of the Atzenbrugger Sündenfall, the charade played by the young people of Schubert's circle in July 1821 that was documented in a watercolour by Kupelwieser. Karl Joseph von Hartmann is in this scene, sitting opposite the pianist Schubert, stroking his chin in puzzlement at the subject of the charade.

Leopold Kupelwieser: Der Sündenfall 'The Fall of Man', 1821, watercolour (Wienmuseum). An illustration of a game af charades among the Schubert friends in the summer of 1821.

Lorenz is justifiably angered by the fact that, even though the image is so definitely not Schubert and has been known to be so for a long time, it is repeated on CD cover after CD cover of Schubert recordings. Unstoppable.

And then we have this, an image which is equally annoying:

Portrait alleged to be by Josef Abel (1764-1818). Unsigned. Undated. The identity of the painter cannot be confirmed with certainty; the provenance of the painting is very obscure; the sitter is not Franz Schubert. But apart from that, everything is fine!

This image appears on CD covers and shamefully also in biographical accounts. This young man is wearing spectacles and is in the vicinity of a piano.

If we apply our common-sense procedure we realise within seconds that this portrait cannot be of Schubert. The face is an elongated trapezoid, the chubby cheeks are missing, the ears are large, the trademark chin dimple is not a dimple but a cleft, the hair is not curly. This portrait simply doesn't look anything like the Schubert we know from the mask and the main portraits. Only the spectacles are a common factor. There is no developmental process that can take us from this young man through the intermediate stops to the death-mask.

Despite this, a number of Schubert specialists[6] have taken this portrait to be of Schubert. One of them[7] even carried out an 'isoproportional analysis' involving 36 pages of hocus-pocus involving line-drawings and overlaid images of skulls and other portraits which 'demonstrated' that this was indeed an image of the young Schubert. Saner voices[8] rebutted the hocus-pocus. We side with them. This is not a portrait of Schubert.

Time for action

Since it is considered bad form in these softie days to hang miscreants from lamp-posts our only available sanction is commercial: never buy a CD with one of these images on its cover; never buy a biography that contains one of these images, even if there is a disclaimer about its veracity: why show it at all? You may as well put a drawing of Donald Duck in its place – it has the same legitimacy. We are sure that this boycott will be really effective and lead to the complete disappearance of the erroneous images in no time at all.

References

- ^ The sculptor and painter Josef Alois Dialer (1797-1846) used the mask in the production of a bronze bust of Schubert for the Währing cemetery in 1830.

- ^ Worgull, Elmar. 'Franz Schuberts Gesichtsmaske und ihre Vorbildfunktion in Zeichnungen Moritz von Schwinds'. Biblos : Beiträge zu Buch, Bibliothek und Schrift, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek Wien. (Werner König zum 65. Geburtstag gewidmet). Böhlau Verlag Wien, 1997, p. 345-388. [DE]

- ^ Steblin, Rita. 'Friedrich Lieders Schubert-Porträt von 1827', Schubert durch die Brille, 1994, p. 93-100.

- ^ Steblin, Rita. 'Schubert und der Maler Josef Teltscher', Schubert durch die Brille, 1993, p. 119-132.

- ^ Schirlbauer, Anna. 'Das zeitgenössische Ölporträt Schuberts hat seinen Maler gefunden: Anton Depauly', Schubert: Perspektiven, Jahrgang 4, Heft 2, 2004, p. 145-173.

- ^ Steblin, Rita. Ein unbekanntes frühes Schubert-Porträt?, Tutzing: H. Schneider, 1992.

- ^ Worgull, Elmar. 'Ein repräsentatives Jugendbildnis Schuberts', Schubert durch die Brille, January, 1994, p. 54-89.

- ^ For example, the renowned musicologist and antiquarian Albi (Albrecht) Rosenthal (1914-2004) in Rosenthal, Albi. 'Zum "Schubert-Porträt" von Abel', Schubert durch die Brille, January 1994, p. 90-91.

Update 19.01.2025

Commentator Kanevas pointed me to the 3D model of Schubert recently created by Hadi Karimi as part of a series of studies of composers. Here it is:

Hadi Karimi, Schubert-3D, ND. Image: Hadi Karimi, Schubert 3D

Karimi was very wise to use the death mask as his starting point for the 3D model. Since this is the only faithful representation we have of Schubert's face the chances are good that the final 3D model may be a very close likeness. Excellent work, Hadi! Thank you, Kanevas!

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!