Zurich-Petrograd, one-way

Richard Law, UTC 2017-03-16 18:54 Updated on UTC 2017-11-19

The Bolshevik revolution in Russia started around lunchtime on Tuesday 3 April 1917 in a cramped room in the seedy Spiegelgasse in Zürich. It would take a week or two more to kick off in all its terrible grandeur, but the start was indubitably at that moment. It would be completed just seven months later, 7 November to be precise, with the collapse of the Kerenski government in Moscow.

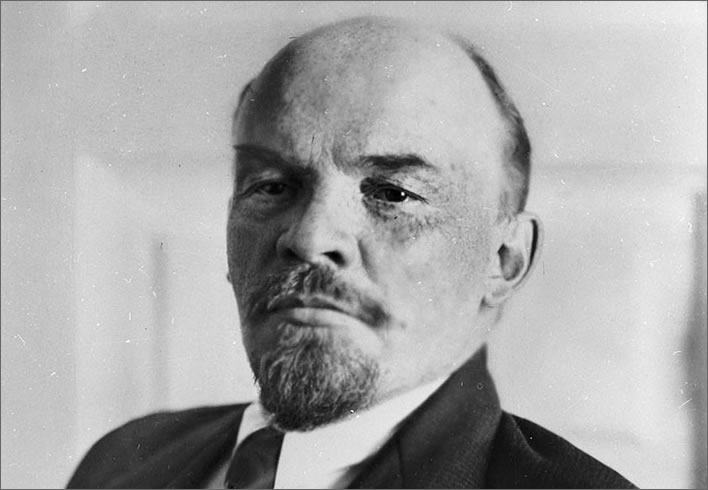

The occupants of the room were Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, better known by one of his aliases, 'Lenin' (1870-1924), and his wife, Nadezhda ('Nadya') Konstantinovna Krupskaya (1869-1939).

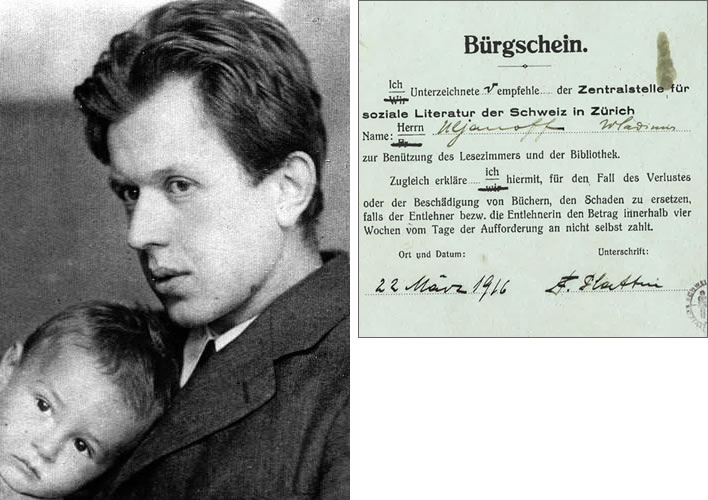

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, ND ©Peter Otsup / Sputnik.

Lenin in Zurich

Why, you may ask, do we find Lenin, that symbol of revolutionary fervour, hanging around in Switzerland, that symbol of bourgeois stability? At the outbreak of the Great War he found himself on Austro-Hungarian territory. A Russian, he became at a stroke a citizen of an enemy country. On 8 August 1914 he was arrested and imprisoned as an enemy alien. After eleven days in prison his contacts in the Austro-Hungarian government secured his release, mainly on the grounds that he was as much against the Russian government as the Austro-Hungarian empire was. He and his wife were allowed to travel to a non-combatant country: Switzerland.

On 5 September 1914 the Lenins entered Switzerland and made their way from St. Gallen to Bern, the capital. Despite their questionable political activity they were given a residence permit. It's always amusing to watch revolutionary hotheads scuttling to the safety of stable, bourgeois democracies when trouble bubbles up. He lasted in Bern until February 1916. However hard he tried, the revolution of the proletariat for which he so longed was definitely not going to start in Bern.

The pair then moved to Zurich, principally because Lenin would have access to much better libraries there. Vladimir Ilyich and Nadya Krupskaya applied for a residence permit on 18 April 1916 and received it without trouble. They extended the permit at the end of the year: they had a good police record and lived quietly and 'fulfilled their obligations' – another way of saying that they paid their rent.

The Lenins became the latest additions to the Russian colony in Zurich. The Russian invasion of Zurich had started in the 1860s. By the 1890s the city's rapidly growing Russian colony was regarded as a centre of revolutionary activity. A satirical carnival song from 1905 mocked the émigrés: 'My head and my heart long for Russia / My belly and my backside prefer Zurich'.

Spiegelgasse 14

Spiegelgasse is in the district of Zurich known as the Niederdorf, the 'Lower Village'. It is now a place of bars, restaurants, boutiques and prostitution. In the nineteenth century it was an area of low-grade accommodation for workers, artists and, in the course of time, émigrés like the Lenins. From the end of the 19th century the authorities in Zürich had made some efforts to improve the area by widening some of the narrow streets.

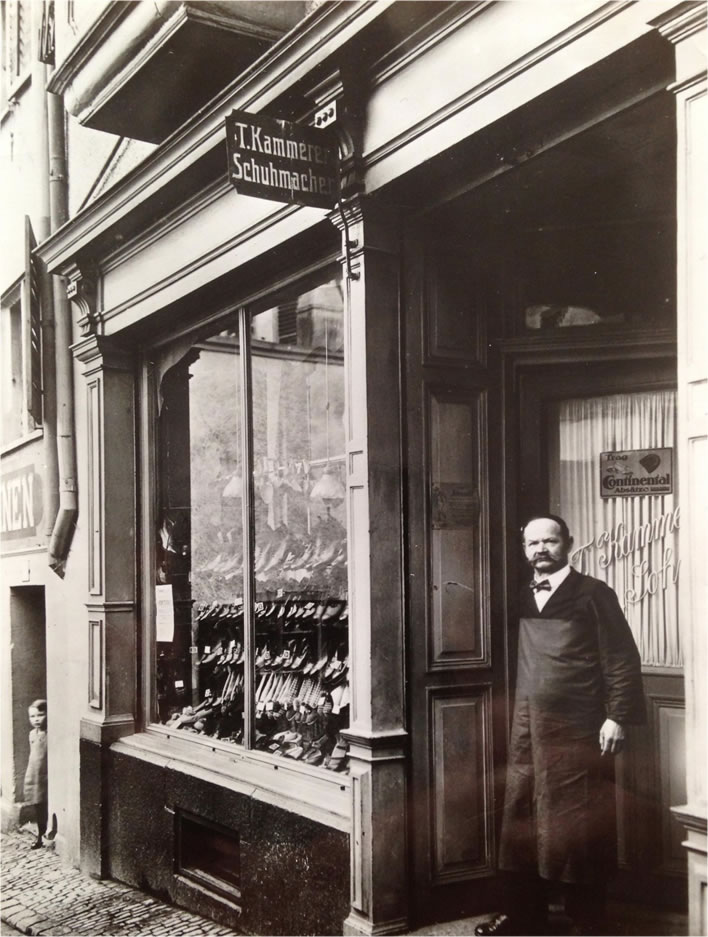

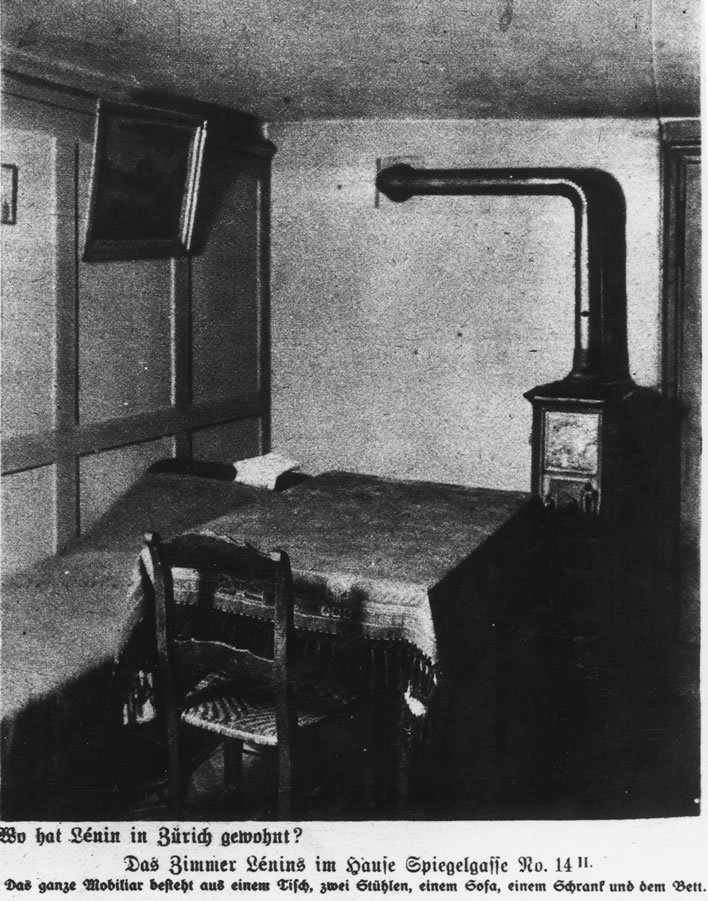

The Lenin's landlord was a master shoemaker, Titus Kammerer (1865-1951), himself a tenant who occupied two rooms with his wife and three children. His workshop was in an adjacent building. He sublet a furnished room on the second floor to the Lenins for 24 CHF a month. (This amount should be treated with caution: there are variants and there is no archival evidence on this point.) He was also sub-letting rooms to the wife and children of a German soldier (a baker), an Italian and an Austrian actor.

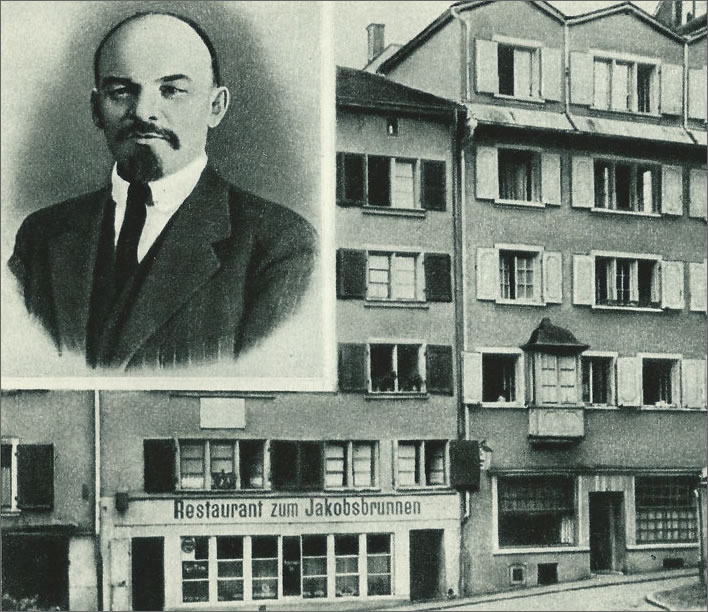

Nadya Krupskaya described the building as 'an old, dingy house almost in the style of the 16th century, with a stuffy, stinking courtyard'. The ground floor of the building was taken up by the Restaurant zum Jakobsbrunnen. The restaurant was taken over in 1954 and became over the following 17 years colloquially known as 'Chez Leo'. According to legend it served the best 'Freiburger' fondue in the city (a fondue made with Freiburger Vacherin cheese).

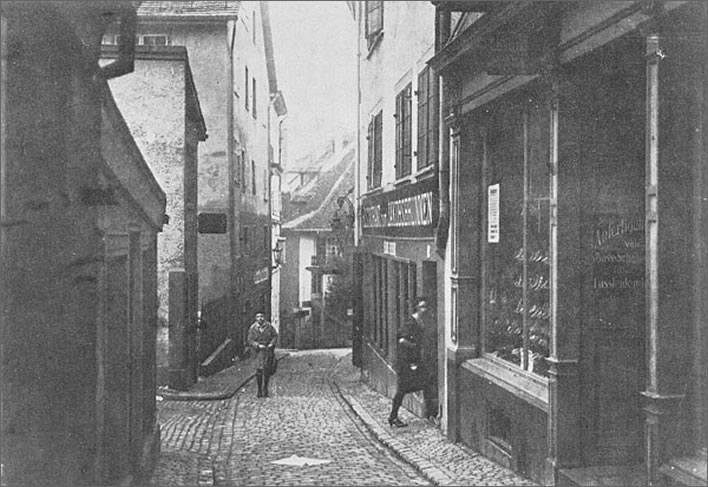

An undated photograph of Spiegelgasse 14, taken before the Lenin plaque was attached in 1928. The entrance to the apartments is on the right, under the street number. The arrow is pointing at the second floor, but not at the Lenins' room. According to the account of Nadya Krupskaya, their room was on the other side of the building, looking onto the courtyard. It is unlikely that she would misremember that fact. Image: NZZ-Archiv.

An undated photograph of Spiegelgasse 14, also taken before the Lenin plaque was attached in 1928. We get a good impression of the narrowness of the street. It seems likely that the shop on the immediate right is Titus Kammerer's shoe workshop.

Titus Kammerer in front of his shop in an undated photograph. Image: Landesmuseum Zürich

A postcard of Lenin and Spiegelgasse 14 produced in Moscow in 1965. The plaque is visible. The open space in front of the building means that the photograph was taken some time in the 1940s, after the demolition of the property opposite. The portrait, inset, covers up most of the building and particularly the second floor, where the Lenins' room was. We note that Kammerer's shop-front seems to have been removed completely. We don't know when Kammerer ceased trading: he would have been in his late seventies at the time of the demolition.

A photograph of Spiegelgasse 14 taken shortly before the demolition of the house in 1971. The plaque is there, as is the illuminated 'Chez Leo' sign of the famed fondue restaurant. The restaurant gives the impression of modest prosperity: it is well-kept and its title has been modishly shortened and styled in a very 60s, Swiss-typography typeface. Image: Bildarchiv ETH-Bibliothek.

Their landlord, Titus Kammerer, is one of the heroes in a tale notably lacking in them. His father and brother were both involved in socialist movements, his nephew was active against Franco in Spain. Some say his brother was instrumental in bringing Lenin from Bern to Zurich. For us this detail doesn't matter. In 1916 Titus was 51 and Lenin 46. The Lenins and the Kammerers got on well. Nadya Krupskaya tells us that they could have found a cheaper room, but stayed on in the Spiegelgasse because of the Kammerers. In Marxist-Leninist theory, the class of educated artisans was one of the most important components of the revolutionary proletariat. Nadya tells us that the Lenins felt comfortable in the presence of the Kammerers and the other residents of the house.

After Lenin became famous Kammerer was pestered and offered large sums by collectors for Lenin artefacts. The Soviet government even offered to buy the interior of Lenin's apartment outright for the Lenin museum in Moscow. He refused all offers. He died in 1951, a cobbler known only unto his customers – apart from having been Lenin's landlord in Zurich.

The building containing the Lenins' room is no longer there. Visitors from around the world turn up at Spiegelgasse 14 to look at Lenin's building, not realising that the building they are looking at has nothing whatsoever to do with the Lenins.

They will read the half-truth on the plaque: Hier wohnte v. 21. Februar 1916 bis 2. April 1917 Lenin, der Führer der russischen Revolution. , 'Here lived from 21 February 1916 to 2 April 1917 Lenin, the leader of the Russian Revolution'. Well, it depends what you mean by 'here': if you mean map coordinates, the statement is true, but if you assume that 'here' means 'in this building' and 'these windows', the statement is a lie. The text on the plaque was true (except for the wrong windows) when it was placed on the building in 1928, against considerable public opposition, we should add. Even the owner of the building (not Kammerer) protested to the Zürich authorities because the plaque had 'reduced the value of the property'. We suspect money changed hands to solve that problem.

The modern fake. There is a kind of poetic justice in the fact that most of the publicly available photos of 'Lenin's apartment' focus on the windows below the plaque, when, in fact, the Lenins lived on the second floor, which would have been the windows above the plaque… except of course that, even if this were their building – which it isn't – their windows would have been around the back in the courtyard. That's enough irreal conditionals for one caption! On a happier note: The courtyard now no longer stinks of the sausage factory that Nadya complained about, but is tastefully greened with climbing plants.

By 1970 the untold millions of corpses in the Soviet Union had been forgotten. Socialism had become quite cool and tourism quite lucrative, so the Zurich city council decided to buy Spiegelgasse 14 and place it under a preservation order. Too late. After 60 years of neglect the building was about to fall down all on its own. It was demolished in 1971. The present day building was erected in its place, the plaque screwed back on and everything was now ready for the tourists. Where once there was the Restaurant zum Jakobsbrunnen, there is now a shop selling 'physical and mathematical objects'.

In today's Spiegelgasse 14 the plaque is the most authentic thing there: it was transferred from the old building to the imposter and affixed thereupon without a blush. The building that used to be in front of no. 14 and which would have robbed the rooms at the front of much light was demolished in the 1940s and left as a pleasant tree-filled space, the Leuenplatz.

Also in the cool 1970s Lenin was given a further plaque in the Zurich Volkshaus, where he had once made a speech.

The Zurich socialists rocking Lenin with a plaque in the Zurich Volkshaus in April 1970. Image: Bildarchiv ETH-Bibliothek.

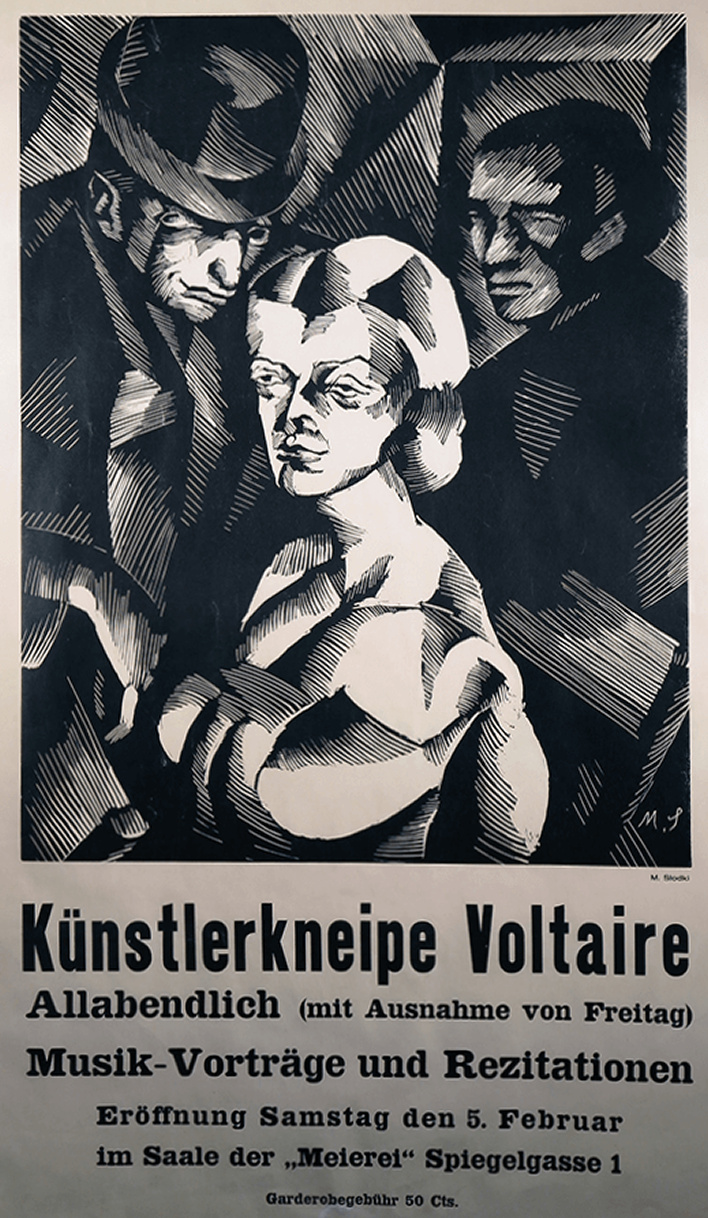

Among literary types the Spiegelgasse is known for two of its former inhabitants, Georg Büchner and Caspar Lavater, but moderns are most likely to recall another building there, the Cabaret Voltaire at no. 1, the birthplace of DADA in Zurich. It opened in February 1916, the same month that Lenin and his wife arrived in the Spiegelgasse. That building has also been renovated over the years into ironic respectability, leaving nothing but the name – elegantly styled, of course – and another plaque. The rather seedy and suspect nature of the district appealed to the DADA-ists, although their outlook on the world was diametrically opposite to Lenin's. All reported sightings of Lenin, that paragon of Russian earnestness, in the Cabaret Voltaire can be immediately discounted.

Marcel Słodki (1892-1943) Cabaret Voltaire 1916. The flyer created for the opening of the Künstlerkneipe Voltaire, the 'artists' bar Voltaire' by Marcel Słodki, a Russian émigré in Zurich, who captures the fine aura of menacing seediness.

If you want an apartment in what is now the urban idyll of Spiegelgasse you will need a lot of money (24 CHF won't do it, sadly), a lot of connections and a lot of patience – form an orderly queue!

Reading for the revolution

Despite its gloom, noise, smells and slightly disreputable surroundings, Spiegelgasse 14 had one great advantage for Lenin: its nearness to the best libraries in Switzerland. During the 18th and 19th centuries Switzerland had been an island of tolerance and free-speech surrounded by stagnant pools of censorship and repression.

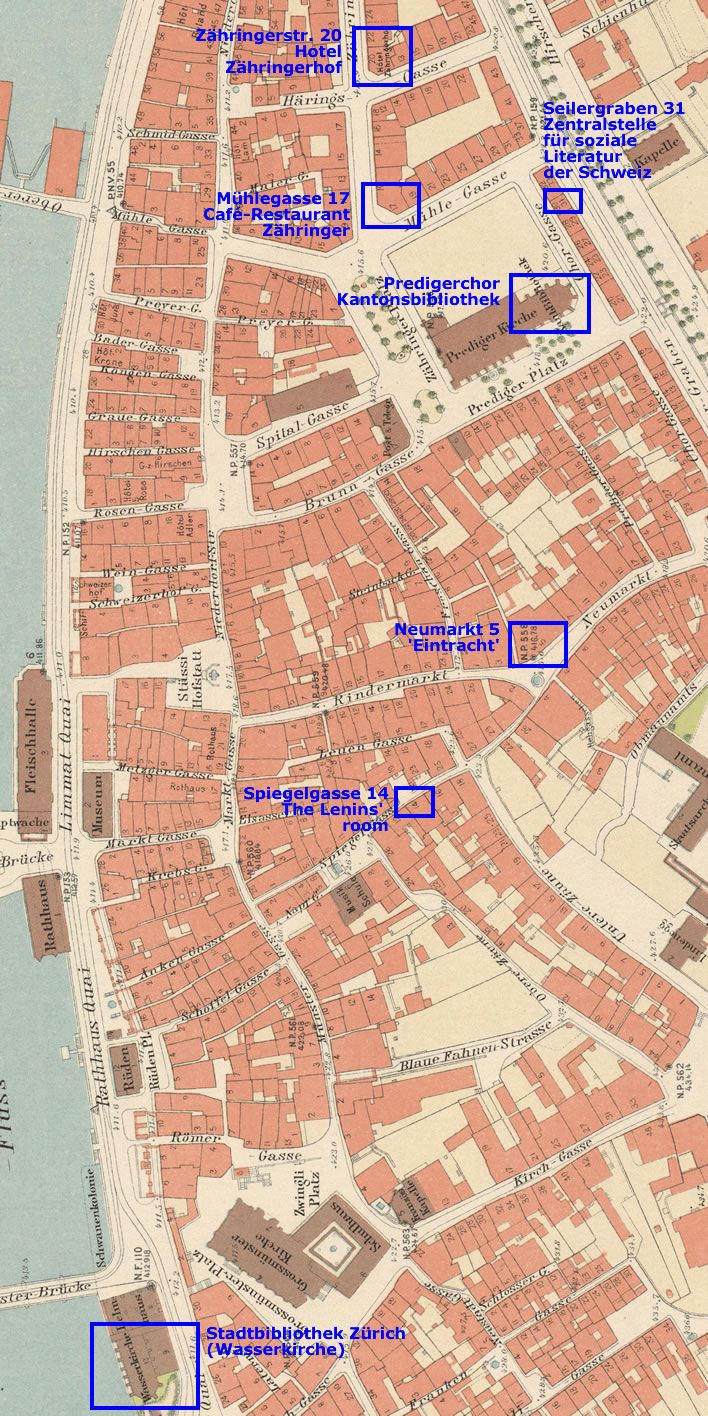

Vladimir Ilyich was a short walk from the Kantonsbibliothek, the 'Cantonal Library' in the choir of the Predigerkirche in the Zähringerplatz and the Stadtbibliothek, the City Library, which maintained an index-card catalogue that covered most of the other libraries in Zurich. Particularly important for him was the Zentralstelle für soziale Literatur der Schweiz, now simply the Sozialarchiv, a resource of exactly the kind of works that Lenin needed for the development of what would later be called Leninism. Its reading room was in the Seilergraben, just next to the Kantonsbiblithek. The area behind the Seilergraben was the academic quarter of Zurich containing the Federal Polytechnic and the University of Zurich.

Lenin's traces on Zurich's right bank. The base map dates from 1900, 16 years before his time. Base map: Stadt Zürich, data layer ©FoS.

An irony with Lenin's departure in April of 1917 is that it coincided almost exactly with the opening of the new Zentralbibliothek in the Zähringerplatz. Lenin never studied there – he had left to start a revolution. The time for studying had passed.

A photograph of the Amtshausplatz in 1914, before the start of the construction of the Zentralbibliothek. To its right is the Prediger Church and its tower, behind that is the Predigerchor in which the Kantonsbibliothek was located, in the background the tower of the new Zurich University building. Lenin arrived in 1916, at which time this was a building site. Image: Ernst Kaufmann, ZB Graphische Sammlung, AWP 9001_02.

Two photographs of the Zentralbibliothek in the Zähringerplatz, just after its completion in the spring of 1917 – the condition in which Lenin would have seen it at his departure in 1917. The street in the background of the lower photograph is the Zähringerstrasse and the building on the corner is the Hotel/Café Zähringerhof, one of the contenders for the location of Lenin's farewell lunch. Image: Ernst Kaufmann, ZB Graphische Sammlung, AWP 9001_30 / AWP 9001_29.

Seizing the moment

But we digress.

On that Tuesday, 3 April, Vladimir Ilyich did what great leaders do, he seized the moment. We grey everyday mice never rise to such instants. Not only that, the instincts and understanding that led him to seize that moment proved to be completely correct. However revolted we may be by Lenin's ruthless and authoritarian politics in pursuit of a lunatic ideology that killed millions of its own people, we have to accept his genius as a leader of men.

To Lenin the moment and the need to seize it were clear:

In Russia a revolution of sorts had just taken place. The Tzar had been overthrown and a provisional government had been appointed on 16 March. But the new government was not universally recognised, the people were hungry and resentful, the troops, incensed by the war in which so many of their comrades had been slaughtered and which showed no sign of ending, were mutinous. The iron was hot for the real, Bolshevik, revolution and the time to strike it had come. Lenin and the Bolsheviks had to return to Russia as soon as possible.

For the Germans, bogged down in the carnage in France, with the prospect of America entering the war at any moment – which it did on 5 April – one of their top strategic priorities was to take Russia out of the war and close down that front. But the new government in Russia just wanted to carry on sending its troops to slaughter as though nothing had changed. In contrast, it seemed almost certain that a Bolshevik government would end the war with Germany. Lenin and the Bolsheviks had to return to Russia as soon as possible.

But how to get them back? Weeks had gone by while the Germans explored the options and the émigrés in Switzerland did what low-grade revolutionaries do: formed a committee so they could ponder the question, wrote reports and circulated papers. It soon became clear that the only practicable route back to Russia went through Germany, Sweden and Finland.

The émigré committee had suggested to the Germans around the middle of March the idea of returning to Russia via Germany. The Germans agreed to the idea almost immediately, but heard nothing more. They were puzzled by the silence which followed that initial request, the silence of a committee doing what committees do – talking, passing resolutions and writing reports.

Two weeks skipped by on wingèd feet. The Germans, desperate to put the idea into action, drummed their fingers impatiently. As the clock ticked and events in Russia moved on, Lenin became as angrily frustrated as the Germans. On the 2 April the émigré committee declared their opposition to a return through Germany. On 3 April Lenin, enraged, finally broke away from them. He seized the moment. One observer [Lunacharsky] described it as an 'act of civil manliness', a manliness that 'Lunacharsky himself did not possess'.

Leaving Zurich

In the morning of that Tuesday 3 April, Lenin took affairs into his own hands. Nadya recalled that moment in her memoirs. Vladimir Ilyich announced to her that he wanted to leave immediately: 'We'll leave on the next train to Bern'. That train departed at three o'clock, leaving just two hours to pack, pay the Kammerers, take books back to the library – a hundred things. Despite Nadya's misgivings, they managed it somehow. All their possessions were in three baskets. We are not sure whether they took all three to Bern with them or left some with Kammerer to collect when they returned to Zurich a few days later. After their final departure they left a suitcase behind, which Kammerer opened two years later – contents: one moth-eaten suit.

Whilst Nadya was packing, Lenin called a meeting at the Eintracht, the meeting rooms in the Neumarkt, just around the corner from their room.

Our punctilious readers can now free themselves of one problem that has been puzzling them for some time. If the Lenins left on 3 April, why does the plaque give their last date of residence as 2 April? Because, we must assume, 2 April really was their last full day of residence.

Neumarkt 5, the Eintracht, meeting rooms and reading rooms around the corner from Lenin's room in the Spiegelgasse. In this photograph an election vehicle for the communists: 'Who fights for an eight hour working day, higher wages, Soviet Russia: only Communists' and 'Vote Communist'.

Lenin persuaded the Swiss socialist Fritz Platten (1883-1942) to act as the intermediary between him and the Germans. Why a Swiss socialist and not a Russian? Because that would allow Lenin to remain at arms length from the Germans. Lenin had his doubts about Platten, but good revolutionaries know how to make do with the tools they have to hand. Lenin suspected that his previous link man, Robert Grimm, was delaying the negotiations for his own purposes. The meeting was brief: there was a revolution to start.

Left: Fritz Platten, the Swiss communist. He moved to the Soviet Union in 1923, the year before Lenin died. He met a very unpleasant end in the Stalinist purges: he was arrested in 1938, endured the terrible conditions of a punishment camp for four years and was taken out and shot after completing his sentence.

Right: The guarantee for 'Ulyanov, Vladimir' to use the library of the Zentralstelle für soziale Literatur, signed by Fritz Platten. Images: Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv

On that Tuesday, 3 April, Lenin, Nadya, Platten and the trusty Zinoviev took the three o'clock train to Bern. At dinner that evening Robert Grimm, despite his objections, was replaced as intermediary by Fritz Platten. Now things started to move. Platten met the German ambassador in Bern at ten o'clock the following morning.

Platten delivered a list of nine conditions from Lenin respecting the journey, the most important of which were: Platten was to be the leader of the transport and sole contact with the Germans; no one must be allowed to enter the 'closed' carriage without his permission; the carriage was to be declared 'extra-territorial'; there must be no passport checks during the journey through Germany and no enquiries into the identities of the travellers; the transit permit for the group was to be based on the exchange of the travellers with those imprisoned or interned in Russia.

This list of conditions reflects Lenin's two main objectives. The first of these objectives was to guarantee the safety of himself and the other travellers. All the authorities on their route to Russia – the Germans, the Swedes, the Finns and even the Russians – would find a carriage full of revolutionary hotheads trundling through their territory: what an opportunity that would have been to clear the decks a little!

The second of Lenin's objectives was to avoid being tainted by German help. Every socialist revolutionary fighting the German state would be suspicious of Lenin's German support. Germany was at war with Russia, meaning that once in Russia, Lenin, had he received German help, would have been a traitor and could have been executed without compunction.

Lenin insisted that the group should pay for their tickets themselves and thus, since most of the group were poor, they would all – at least nominally – travel third class. The cash for the fares was ostentatiously handed over to the Germans at the start of the journey. The fare for the journey must have been computed from some nominal ticket price, since the costs of the journey they really made in that special carriage would have been immense.

The compartments of the carriage in which the group travelled were declared to be extra-territorial space, meaning that, for lawerly minds like Lenin's, the group never entered Germany at all.

One last Swiss lunch and one more speech

Finally, on Easter Sunday 8 April, all the pieces came together. The group would depart from Zurich on Easter Monday 9 April. Lenin had selected a group of around 32 people to go with him to Russia. Only about 19 of these were hard-bitten Bolsheviks. Some were from the Jewish socialist group, there were even children in the group. Some travellers joined Lenin in Bern, many coming from Geneva. They all met up at the Volkshaus in Bern and travelled with him to Zürich on the morning of the departure, some others travelled directly to Zurich.

The Volkshaus in Bern, which Lenin used as a base during his negotiations with the Germans in the final phase of planning the journey to Russia. It is now the four-star Hotel Bern, a business hotel and seminar venue, a temple to capitalist consumption.

When it opened in October 1914 it was a temple to socialist extravagance, a meeting point for socialists where the members of the bourgeois parties would never set foot. It contained an 800-seat theatre, a 300-seat restaurant, reading and library rooms, ten rooms for clubs and associations, 52 hotel rooms and a public bath-house with 25 bathtubs. Renowned artists were hired to work on every detail of this project. Paintings and great murals were specially commissioned. In 1917 it offered Lenin and his travellers a complete revolutionary infrastructure: his telegrams in those days were sent from and sent to the Volkshaus.

The structure lasted barely fifty years. From the 50s onwards it was renovated into extinction. The hotel was opened in 1983 and the only thing left now is the monumentally ugly facade, an early exercise in building in concrete.

The Lenins had packed three baskets with clothes, blankets, books and newspapers (indispensable for revolutionaries) and even a kerosene stove. We assume that they left these baskets with the Kammerers before their departure to Bern and collected them when they returned to Zurich.

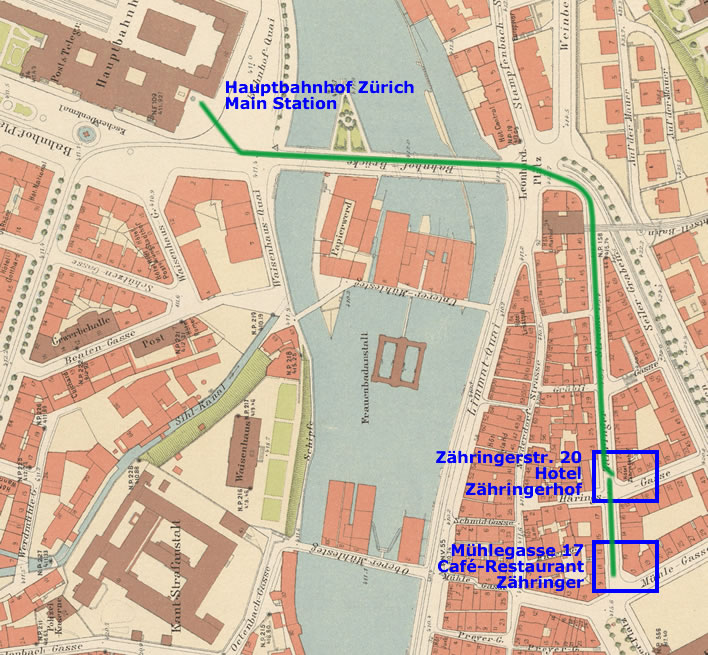

Once in Zurich the Bolsheviks in the group gathered for a farewell lunch. There is a large degree of uncertainty about the details of this eventful meeting. Some say there were 16 people there, some say about 22, some imply it was all 33. Lenin made a speech setting out his revolutionary programme, which is the sort of thing that is expected of revolutionaries.

Some say that the lunch took place in the restaurant of the Hotel Zähringerhof. This was in the Zähringerstrasse 20 and also part of the Niederdorf, thus not far from the Lenins' apartment in the Spiegelgasse. The Hotel Zähringerhof ceased trading around the beginning of the 1920s. Perhaps with the loss of so many Russian émigrés from 1917 onwards it lost too many customers. It was replaced by a manufacturer of pewter ware and is still today in that family's hands: Braumandl Zinn, 'Braumandl Pewter'.

Zähringerstrasse 20, now with the pewter-ware shop Braumandl Zinn on the ground floor. The building was erected in 1879. The ground floor was taken up by the restaurant of the Hotel Zähringerhof, the kitchen for which was in the basement. At the time the Braumandl family moved in there were four apartments above the restaurant. When the restaurant ceased trading the kitchen in the cellar was transformed into a pewter foundry.

A photograph of the modern Zähringerstrasse, the presumed route of Lenin and Co. to the station, looking from the Zähringerplatz towards Central. The bridge carrying the 'Polybahn' can be seen in the distance, the steep rack railway that runs from Central to the Polytechnic terrace. Erected in 1889, the Polybahn was there in Lenin's time.

Some say, however, that the lunch took place in the Café-Restaurant Zähringer, on the corner of Zähringerstrasse and Mühlegasse. This business was owned by someone who was a member of the Swiss Socialist party, which may mean nothing at all. The building is now the Hotel Scheuble.

If all these Zähringers – the name of one of the great feudal dynasties in the region in medieval times, quite ironic in the present revolutionary proletarian context – are causing your head to spin, don't worry. The two places are only 50 metres apart. Stylish writers like to date the start of the Bolshevik revolution with the touching scene of the group of thirty or so travellers stumbling out of one of the 'Zähringers', laden with luggage, bedrolls and baskets, struggling with their burdens down the Zähringerstrasse for a couple of hundred metres to the Leonhard Platz (now Central, one of the great tram nodes in Zürich), then over the road and then another 200 metres until they reached Zürich Hauptbahnhof.

The march to the station in Zurich. It is interesting, but possibly without further significance, that the Hotel Zähringerhof is specifically labelled on this map from 1900. The building dates from 1879, when the Zähringerstrasse was laid down in an attempt to open up the dismal warren of the Niederdorf, which in turn means that the restaurant had been established for about 20 years by the time the map was drawn. The building containing the Café-Restaurant Zähringer was erected around 1871 and contained mostly offices. Base map: Stadt Zürich, data layer ©FoS. NB: the texts on this map were updated on 19.11.2017.

They were indeed a rather odd-looking group: Vladimir Ilyich short and stocky, a man in his mid-forties with a goatee beard, wearing a threadbare overcoat, a crumpled hat and chunky mountain boots (Kammerer's work); the others affecting all the stylistic diversity of revolutionary Russian émigrés. As they left the restaurant they were probably not laden down with bags: commonsense suggests that most of them had left their mountains of bags in the charge of the non-political members of the group on Zurich station.

Uproar in the station

Although the diplomacy behind the group's journey to Russia was secret, keeping the fact of the journey itself secret had been impossible, given the gossipy turmoil within the Russian émigré community in Switzerland and throughout Europe. Lenin knew his fellow troublemakers well: to the purists the taint of a preferential deal with the feudal German state would hang around him whatever legal sophistries he came up with. It was therefore no surprise to anyone that a crowd of Russians – the disaffected and the not-chosen – were waiting inside Zurich railway station.

Inside the station there were tumultuous, noisy scenes but no real violence: the travellers were called provocateurs, German agents, scum, swine. Many of those there had, let us say, an equivocal relationship with the authorities of any nation, so to see the German authorities oiling the wheels for Lenin and his group was highly suspect. There was speculation that money had changed hands, that Lenin and his group had even received money from the Germans.

Their scheduled train pulled out of Zurich station at 15:10. The group would change to a special carriage that was waiting for them at Gottmadingen, over the border in Germany.

Crossing borders

In all the accounts of Lenin's journey this intricate piece of wartime border crossing causes much confusion. There was, for example, no direct connection from Zurich in Switzerland to the little village of Gottmadingen in Germany. Gottmadingen is on the line to Singen, the next major town, also in Germany, but there was no direct service between Zurich and Singen.

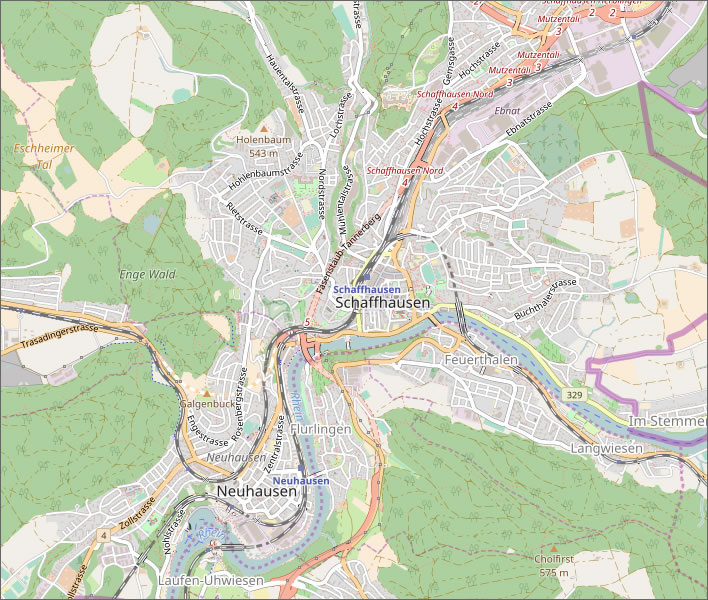

Schaffhausen, an important railway confluence in northern Switzerland. The German line enters at middle left, passes through the station and exists top right. The line from Zurich-Winterthur at bottom right, passes through the station and continues as the line to Bulach. The situation in 1917 was fundamentally the same.

The train the travellers boarded in Zurich was a scheduled Swiss Federal Railways train that went from Zurich via Winterthur to Schaffhausen. Their train from Zurich certainly did not just continue from Schaffhausen on to Gottmadingen. At Schaffhausen the group would have to change to a scheduled train on the line that runs from Basel, Waldshut, Schaffhausen, Singen and Konstanz. This line was part of the Großherzoglich Badische Staatseisenbahnen, the Grand Duchy of Baden State Railways.

Schaffhausen, town and canton, is a peninsula of Switzerland that juts into German territory. Over centuries the Swiss and the Germans have worked together in an exemplary fashion in the cause of economic normality in this peninsula. The Germans even owned 48% of the station at Schaffhausen, for instance, and railway enthusiasts would be astonished at the mix of station ownership, narrow and broad gauge, left, right travel and single track lines within this small region. Reflecting the economic importance of transport for the region, during the two decades around the turn of the century the railway network in the area had been ceaselessly developed and extended. The line Schaffhausen-Thayngen-Singen along which our Leninists travelled had been upgraded to double-track only a few years before, in 1908.

The train our group took to get them from Schaffhausen to Gottmadingen was operated by a German railway operator, so for the legally-minded among us they were indeed on a German train, but on Swiss territory as far as the small station of Thayngen. The line then crosses the border into Germany and arrives after about 5 km at Gottmadingen, the first full station on the German side of the border. The journey from Schaffhausen to Gottmadingen takes about 15 minutes.

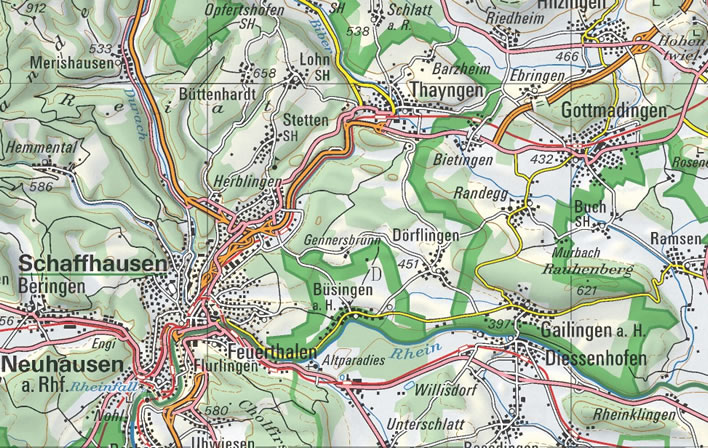

![A map of the line Schaffhausen-Thayngen-Gottmadingen-[Singen] from 1904.](../../img/2017/03/schaffhausen-region_6_708x446.jpg)

A map of the line Schaffhausen-Thayngen-Gottmadingen-[Singen] from 1904. The line runs from the north of Schaffhausen to Thayngen (top centre), where it turns east, crosses the border from Switzerland into Germany (dotted line) and proceeds to Gottmadingen (top right).

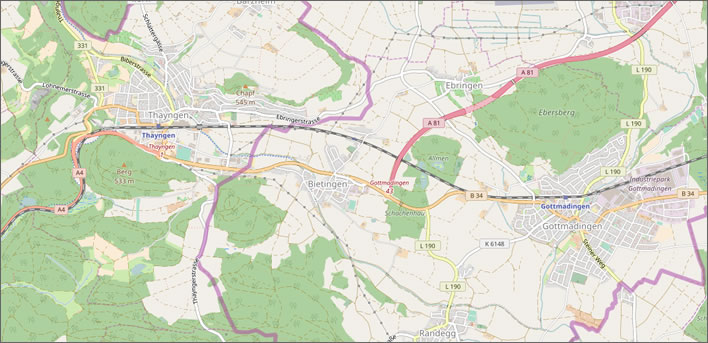

A modern view of the railway lines (solid red) around Schaffhausen – little has changed. The German east-west line enters bottom left at Beringen. The line from Zürich-Winterthur enters at bottom right. After passing through Schaffhausen station the German line exits north and passes through Thayngen, then over the Swiss-German border (green) and then to Gottmadingen. During the planning of the line both Thayngen and Gottmadingen petitioned to have the line built through the centres of their villages, which brought them economic growth compared to, say, Biethingen, which stands aside from the line and has only a small halt.

The modern line between Thayngen and Gottmadingen. The Swiss-German border is in lilac.

At Gottmadingen the travellers left the scheduled German train and climbed into the 'extra-territorial' carriage waiting for them there. Their short sojourn on the platform of Gottmadingen station was technically – though trivially – on German soil. It may be that the vagueness of all accounts on this point over the last century derives from this legal tangle. Certainly, neither the Germans nor the Bolsheviks would want to make this 10 km long breach of extra-territoriality too obvious.

The train journey only became exceptional (or 'unscheduled') once they reached Gottmadingen station and climbed into the waiting 'extra-territorial' carriage. All transport so far had been by scheduled services.

We are told credibly that the travellers had dealings with the Swiss Customs at Schaffhausen and at Thayngen, which has been interpreted by the conspiracy-minded as some peculiar form of Swiss persecution of the travelling Leninists. The customs checks were quite in order, if slightly paranoid. There was a customs post at Schaffhausen to deal with the traffic entering or leaving Germany. There was also a Swiss Customs post at Thayngen, which was located immediately next to the border.

Photograph of Thayngen ('Thaingen') railway station taken around 1900. Image: Heimatmuseum Thayngen.

From the accounts of the travellers it seems that the corresponding German Customs agents had no contact with Lenin's group. Lenin's carefully worked out agreement with the German authorities explicitly specified that no identity checks were to be carried out by Germans en route. We can reasonably assume that the German Customs officers in Schaffhausen and in Gottmadingen had been instructed to go for a tea-break at the appropriate moments. The interest of their Swiss counterparts in this band of travelling revolutionaries may have been piqued, who knows? The Swiss Customs, though, were not parties to the Lenin-German travel pact and checked the travellers' identities and luggage with their usual thoroughness.

An insight into the Swiss role (that phrase just had to be written!) in the affair came nearly three years after this momentous event when, – embarrassingly behind the times – the Swiss Foreign Ministry read in the papers that a former resident of Spiegelgasse 14 in Zürich was now the leader of revolutionary Russia. They wrote to the Swiss Secret Service, the Department of Transport and the Customs Service asking them to explain what had happened on that 9 April 1917.

The Secret Service replied that they had no knowledge at all of the journey. The Department of Transport asked the Federal Railway, who also knew nothing – why should they? It had been a normal, scheduled train service that Easter Monday. Only the Customs authorities had any paperwork. The customs officers had just done their duty and checked the group's belongings and travel food. There had been only one Swiss citizen in the group, Platten, the rest were just a group of alien nonentities. If they chose to leave Switzerland, that was their decision.

No one in the Customs office in Schaffhausen had any memory of a troupe of thirty Russian revolutionaries passing through – a fact which we paranoids find comforting. The Customs officer in Thayngen had a vague memory of Herr Lenin's 'exceptional politeness'.

It was probably also a good move to have Platten, a native speaker of Swiss German, at their head: had that thought also occurred to Lenin when he selected Platten as their leader on the journey? Just one more question we cannot answer.

Swiss snack stealers

Under normal circumstances customs officials are unconcerned about what goods may be leaving their country. But these were not normal circumstances, this was wartime, there were food shortages in Switzerland, but the shortages in Germany were much worse. It was of interest to the Swiss that their food did not end up on German tables.

There is therefore probably some truth in the assertion that the Swiss Customs officials confiscated some of the group's food, particularly their sweets and chocolate, but the accounts seem to have been exaggerated as the years have rolled by. Travellers were allowed to have food for themselves for the journey. Anything more than that was a matter of interpretation. The customs officer's gratuitous remark about the politeness of the group implies that there was no draconian seizure of food or troublesome protests. The tales of heartless confiscations all appear to arise from Fritz Platten's account, written seven years later. Platten, a relatively hard-left Swiss socialist, felt no love for Swiss authority in any form.

Germany at last

At Gottmadingen a special carriage composition was waiting for them: an engine, a green carriage with eight compartments and a baggage-van. There were three second-class and five third-class compartments. This carriage would be their home for the duration of their journey across Germany. According to the terms of the agreement with the Germans, this carriage composition was declared to be an extra-territorial space. An end compartment, out of bounds to the Russians, was occupied by the German escorts.

There were two potentially dangerous moments during the entire journey of the group to Petrograd. The first of these was their descent from the scheduled train from Schaffhausen onto the platform at Gottmadingen. This was the nervous moment of truth when the honesty of the Germans' intentions with regard to the Russian revolutionaries was tested. Apart from the Swiss national, Fritz Platten, all the other members of the group were technically enemy aliens, just as Lenin had been in Austro-Hungary at the outbreak of the war. If they were going to have trouble with the Germans, it would happen on Gottmadingen station.

Some subsequent headlines described the carriage as being 'sealed' (plombiert), but this word is an over-dramatisation that was helpful to both sides. The reality seems to have been that three of the four doors on the platform side of the carriage were locked in order to restrict entry to and exit from the 'extra-territorial', Russian, section of the train. A chalk line was famously drawn across the corridor of the waggon to separate the German end compartment from the Russian compartments. The fourth, unlocked door was at the German end and could only be used by Platten or the German escorts. Only Platten could cross this line, the German escorts had to stay in their compartment, their exit door in the carriage was the only route to German soil. There is no certainty that anyone bothered to lock the track-side doors. The Russians therefore did not have access to 'German territory', that is, the end third-class compartment occupied by the two German escorts. There was a toilet at the Russian end of the carriage and one at the German end.

The chief German escort, a 'politically tactful officer', was one Arwed Freiherr von der Planitz, a 42 year-old member of the Deputy General Staff, a captain in the Sächsischen Gardereiter, the Saxony Horse Guards. An amusing choice to accompany a carriage full of revolutionary Russians, since von der Planitz was himself a scion of old German nobility and his regiment one of the most feudal regiments in the old German Army, an equivalent of a regiment of the Household Division in Britain.

The Austrian ambassador to Switzerland, who as a citizen of the feudal Austro-Hungarian Empire knew a thing or two about aristocracy, pointed out the irony of the appointment of such an aristocrat from such an aristocratic regiment as 'a kind of cavalier of honour to this Russian revolutionary rabble'. The cavalier of honour and his subordinate, Lieutenant von Buhring, collected up the fares of the travellers in Gottmadingen. They must be the poshest ticket collectors in railway history. Then they all climbed in and set off. Around 3,500 km and seven days away, a revolution was waiting.

To the Finland Station

Groans turn to smiles as our suffering readers now learn that we are going to treat the remainder of Lenin's journey very briefly. The details of the journey have their attractions for specialist historians, but in essence, the revolutionaries sat in their special carriage and were pulled by various locomotives and attached to various trains as they trundled north through Germany to the Baltic port of Saßnitz, where they abandoned the carriage. In Germany, once they reached main lines and their carriage was coupled to scheduled trains they had access via Platten and their escort officers to food from stations and restaurant cars.

The romantic notion of an entire special train, particularly a 'sealed' one, travelling to Russia is simply nonsense. The Leninists occupied one carriage and a baggage-van with their extra-territorial status only for the duration of their transit through Germany.

The first part of the journey through Germany from Gottmadingen to Frankfurt am Main was convoluted, resulting from the need to avoid disruption of military transports. From Gottmadingen the train went a short way down the track to Singen and waited there overnight. It left Singen early on Tuesday 10 April. The locomotive was changed in Tuttlingen, where they entered the network of the Württemberg State Railways and from there took a complex route to Stuttgart.

From Stuttgart the train headed towards Mannheim, changing locomotives at Bretten, where it returned to the Baden network. After yet another change of engine, this time in Mannheim, the carriage travelled via Darmstadt to Frankfurt am Main. Their arrival at Frankfurt marks the end of the 'custom-made' part of the journey; from now on, apart from a complicated circumnavigation of Berlin, their carriage and baggage-van composition would be coupled to scheduled trains.

In the morning of Wednesday 11 April their carriage and baggage-van were attached to the scheduled morning restaurant car express from Frankfurt to Berlin, arriving that evening at the Potsdamerbahnhof. There was an unexplained delay in Berlin at a deserted station overnight which has puzzled conspiratorial minds: some think there could have been a meeting with high-ranking German representatives. It seems unlikely, but, who knows? Finally, their carriage and baggage-van were taken on a circuitous route around Berlin to the Stettinerbahnhof, north of the city. On the morning of Thursday 12 April they were coupled to the scheduled train from Berlin to the Baltic ferry port of Saßnitz, about 250 km to the north.

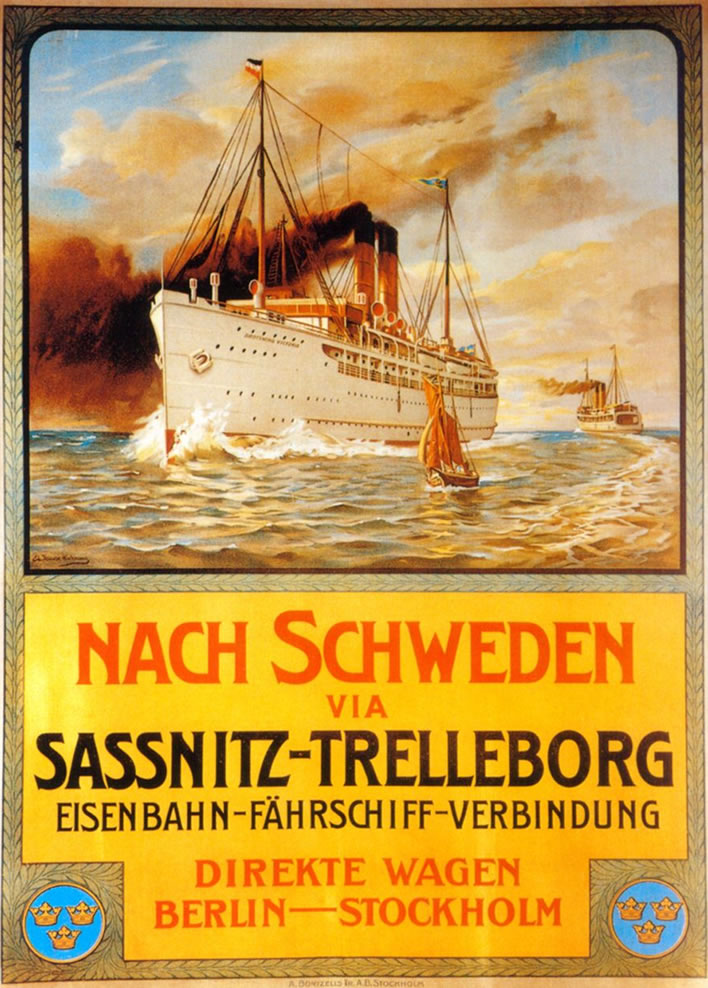

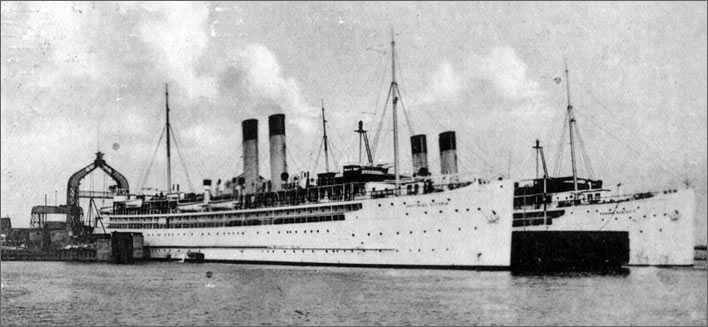

Top: A poster from 1909 advertising the ferry and particularly the direkte Wagen Berlin-Stockholm the direct, roll-on-off carriages between Berlin and Stockholm. The ferry shown is the Drottning Victoria, the 'Queen Victoria' (no, not that Queen Victoria, another, Swedish, one) on which Lenin's group travelled. The amount of smoke proudly shown exiting the funnels tells us that we are still in the great age of steam.

Bottom: the Drottning Victoria and the Konung Gustaf V in Trelleborg Harbour in 1919.

Saßnitz is on the island of Rügen, so the travellers' carriage and baggage-van had to be ferried over the Strelasund. The ferry between Saßnitz in Germany and Trelleborg in Sweden was a rail ferry, which could carry through carriages to Stockholm. It seems unlikely that Lenin's composition was loaded onto the ferry – why would it be needed in Sweden? It is more likely that Lenin's group boarded on foot and their special 'sealed' carriage was left behind in Germany. It had served its purpose. From now on the rest of the journey would be undertaken on scheduled, public transport. The crossing on the Swedish steam ship Drottning Victoria was around 100 km long and took about six hours. It was rough and we are told that most of the Leninists became seasick.

On terra firma once more in Trelleborg, the group caught the evening train to Malmö, about 23 km away. The need for discretion had passed. At Malmö they boarded the scheduled night express to Stockholm. The party spent most of Friday 13 April there. Lenin was prevailed upon to go shopping and replace Kammerer's mountain boots with respectable revolutionary shoes and a pair of respectable revolutionary trousers.

Lenin, front centre with the umbrella, in Stockholm.

After that day of dining and retail therapy the group left Stockholm on the sleeper to Haparanda, a town 900 km to the north on the border Swedish-Finnish border. They arrived on Saturday 14 April. The group disembarked from the train and crossed the frozen stream on horse-drawn sledges to Tornio in Finland.

If the first really dangerous moment of the journey had been the test of the Germans' word on Gottmadingen station, the second dangerous moment came in Tornio. For a century Finland had been a vassal state of Russia. It would only declare its independence seven months later. This moment was, in effect, the moment when the group crossed into Russia.

At Tornio station they were not arrested or summarily shot, but each and every one of the travellers was strip searched and interrogated thoroughly. The whole process took a day and involved British officers, who had been posted there to support their Russian allies. The British were not happy about it, but ultimately felt that they could do nothing to stop Russian citizens entering Russian territory. Finally, that Sunday evening, 15 April, the group was able to board the Russian train that would take them to Petrograd, more that 1,000 km away. Since the group had left Stockholm it had travelled about 1,000 km northwards, then 1,000 km southwards.

On Monday 16 April 1917 at about eleven at night Lenin and his group arrived at the 'Finland Station' in Petrograd. They had left Zurich on Easter Monday of the western church calendar and arrived in Petrograd on Easter Monday of the eastern church calendar. They were given a tumultuous reception. Lenin had been right: the iron was hot and waiting to be struck. Strike it he did: only six months later he would be the leader of Bolshevik Russia.

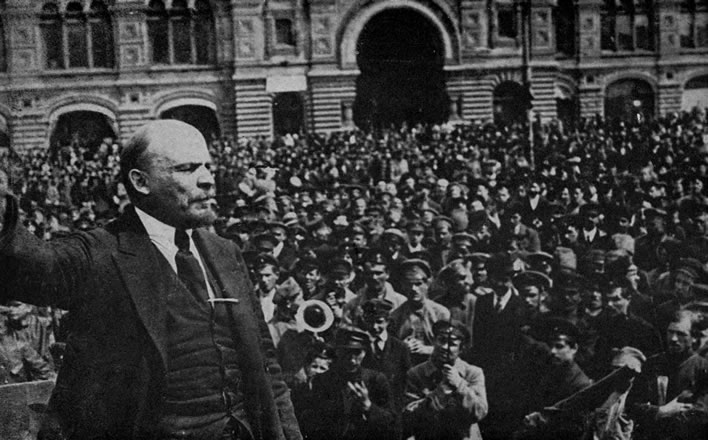

Lenin doing what the Germans had transported him to do: rousing the Russian masses.

The key German hope in facilitating Lenin's journey was fulfilled: on 15 December 1917 a German-Russian armistice was called and on 3 March 1918 a peace treaty was signed. Despite this, only nine months later the armistice of 11 November signalled utter defeat for the Germans and their allies in the 'war to end all wars'.

A number of transports of Russian émigrés from Switzerland followed, but without such extraordinary precautions. This fact alone reminds us that the complexity of this transport was entirely of Lenin's doing. The Germans had been willing to give Lenin and his revolutionaries a free pass to travel without hindrance through Germany. The 'sealed train' was a legal fiction for Lenin that ultimately proved unnecessary, although Lenin might say to us now that he wasn't to know that before he had arrived in Petrograd. The two short stretches where the extra-territorial fiction could not be maintained – travelling on the German train on German lines to Gottmadingen and leaving their 'sealed' carriage to board the ferry in Saßnitz – never made it into the records.

Winston Churchill famously raged at the Germans and the 'sealed truck' containing the 'plague bacillus' that they had sent into Russia, but he should also have raged at the Swedes, whose socialists provided a comfortable and well-fed transit for Lenin's group to Finland/Russia. The limp-wristedness of British officers in Tornio should also not go unmentioned in this context, but to be fair, as far as they were concerned Lenin's group was just a rag-tag bunch of nonentities.

The Austrian author Stefan Zweig, released from military service in Austria, was hanging around Zurich at the time of Lenin's departure. He recounted a version of the journey of Lenin's 'sealed train' as one of his 'twelve historical miniatures' in his 1927 book, Sternstunden der Menschheit, 'Decisive Moments for the Human Race' (first published in English as The Tide of Fortune, 1940). Of all the artillery shells fired in the Great War, he notes, the one with the greatest destructive power was Lenin's 'sealed train'.

The Irish writer James Joyce was also hanging around in Zurich at this time. He was writing the first stages of his novel Ulysses and his mind was full of Odyssean parallels. We are not surprised therefore, when told of Lenin's journey, he thought not of plague bacilli or artillery shells but of the instrument of deception devised by Odysseus that would break the siege and give the Greeks the victory: to him, Lenin's sealed train seemed just like the Trojan Horse. He also foresaw the unplanned consequences: 'Ludendorff must be pretty desperate'. Indeed he was.

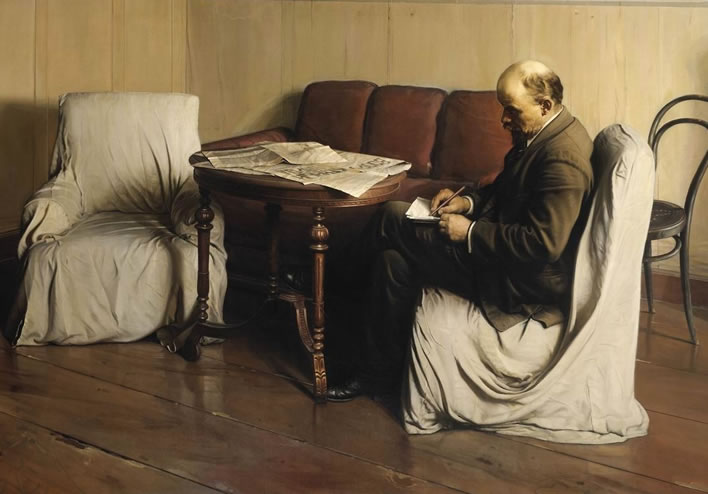

Brodskiy, Isaak Izrailevich, Vladimir Lenin in Smolny, 1930. During the early months of the revolution the Revolutionary Committee set up its headquarters in the 'Institute for Young Noble Ladies' in the district of Smolny in Petrograd. Image: The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Acknowledgments

The main sources used for this article are:

- Bölsterli, Hans. 'Daten zur Schienenverkehrsgeschichte der Region Schaffhausen', Schaffhauser Beiträge zur Geschichte, 61, 1984, p. 65-95.

- Gautschi, Willi. Lenin als Emigrant in der Schweiz, Benziger, Zürich / Köln 1973.

- Hahlweg, Werner. 'Lenins Reise durch Deutschland im April 1917', Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, 1957, p. 307–333.

- Krupskaja, Nadeschda. Erinnerungen an Lenin, Dietz Verlag GmbH, Berlin, 1959.

- Pearson, Michael. The Sealed Train, New York, 1975.

- Platten, Fritz. Die Reise Lenins durch Deutschland im plombierten Wagen, Berlin 1924.

- Rappaport, Helen. Conspirator: Lenin in Exile, Random House, 2009.

- Senn, Alfred Erich. 'New Documents on Lenin's Departure from Switzerland, 1917', International Review of Social History, 19(2), August 1974, p. 245-276. doi:10.1017/S0020859000004648

- Skelsey, Geoffrey. 'From Lake Geneva to the Finland Station...', BackTrack, April 2015, vol 29, no 4, p. 236-239

- Zimmermann, Jürg. 'Beiträge und Dokumente zur Geschichte des Bahnhofs Thayngen', Schaffhauser Beiträge zur Geschichte, 61, 1984, p. 43-64.

Update 25.04.2017

Added a photograph of Titus Kammerer standing in front of his shop here.

Update 19.11.2017

Some photographs related to this article from the Zürich Baugeschichtliches Archiv.

Some images of the Spiegelgasse

Lenin died in January 1924, his wife Nadya Krupskaya in February 1939. He was already dead, his physical presence gone from the world, by the time most of these photos were taken.

The many photos in the Baugeschichtliches Archiv of the Spiegelgasse and its environs reveal an 18th century town structure – arguably also medieval – that lasted for a remarkably long time into the 20th century. There is a dense weave of small flats and workshops: shoemakers, furriers, bakers, carpenters, plumbers, electricians and so on, interspersed with flats and restaurants. It would not have been a quiet place to live: we can understand why the Lenins fled their room for outdoor spaces as often as they could. Whereas Karl Marx, that early sociologist, saw such physical and economic structures as the base upon which culture rested, Lenin probably couldn't care less – he just needed newspapers and libraries.

The interior of the Lenins' room on the second floor of Spiegelgasse 14 above the Restaurant zum Jakobsbrunnen. The room was at the back of the house and the single window looked out over the courtyard. According to the caption under the picture, the Lenins' only furniture was a table, two chairs, a sofa, a cupboard and a bed. Image: Photographer Wilhelm Gallas(?). No date. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

Spiegelgasse 14 and the Restaurant zum Jakobsbrunnen in the year 1927. The memorial plaque to Lenin was put up the following year, 1928. Titus Kammerer still had his cobbler's business: part of his shop-sign is visible centre right. Image: Photographer Wilhelm Gallas. 1927. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

This image, taken in 1937 after the demolition of the houses opposite, has a number of interesting features. On the left of the picture, at house No. 16, we see the sausage factory and butchers shop of Otto Ruff, which produced the unpleasant smells and smoke that Nadya Krupskaya tells us about in her memoirs. During the Lenins' residence it was probably still operating under the name of Otto's father, Pius Ruff (1859-1925) a German from Jungingen in Baden-Württemberg who had arrived in Zürich in 1877. Pius married a Swiss girl in 1884 and brought the business to fame and a substantial fortune. Otto died in 1944, at which point the business passed down to his son Rolf. The company fell apart after the Second World War.

Titus Kammerer's cobbler's shop can be seen at No. 12, just beyond the restaurant. He seems to have been still trading – his business sign is over the door and there appear to be shoes in his windows – even though he would have been 72 at the time this picture was taken. No. 12 is the house where Georg Büchner (1813-1837), the German writer – another hounded revolutionary (Dantons Tod, Woyzeck etc.) – lived for a brief period until his death. The white plaque in his memory can be seen just above Kammerer's shop windows.

Image: Photographer Ludwig Macher. 1937. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

Spiegelgasse 14 and the Restaurant zum Jakobsbrunnen in 1938. Image: Photographer Ludwig Macher. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

A photograph from 1939, two years after the similar view of this group of buildings above. The facade of No. 14 has been repainted and the restaurant signboard redesigned. Titus Kammerer's trade sign has gone, although there appear to be shoes still in the window. Poor Georg Büchner's plaque appears to have been covered up with a sign Wohnung zu vermieten, 'Flat to let'. Image: Photographer Ludwig Macher. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

By 1940 Titus Kammerer's shop is now empty. The Büchner memorial plaque is still there. Image: Photographer Ludwig Macher. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

A close-up of Georg Büchners memorial plaque on Spiegelgasse 12 in 1940. The flags suggest that the photo was taken on or just before the Swiss National Day, 1 August. The picture also shows us a specimen of that creature, the eternally curious resident of Zurich with the critical gaze. Image: Photographer Wilhelm Gallas. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

By 1944 Titus Kammerer's shop has become the Restaurant zur Laterne. The facade of the building has been cleaned up and the shutters replaced. Buchner's plaque has been removed and replaced by an inscription running above the lintel of the ground floor. The condition of house No. 14 continues to decline. Image: Photographer Heinrich Wolf-Bender. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

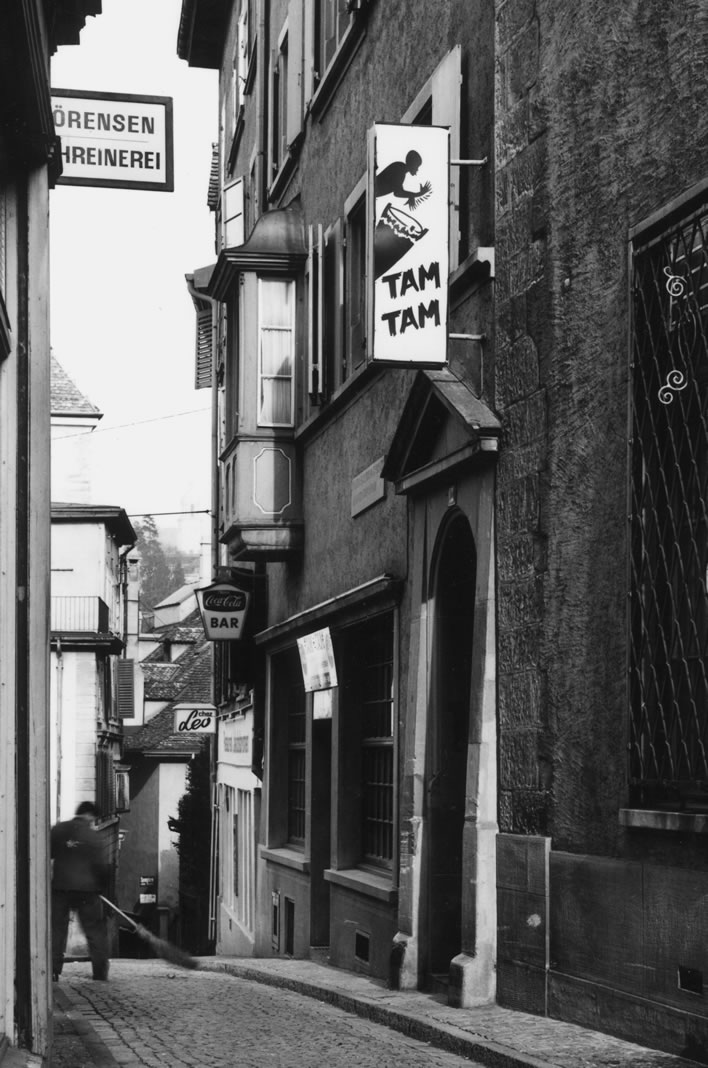

By 1967 the decline in the substance of House No. 14 continues. We might think that it was unoccupied if it weren't for the little boy hanging out of a third-floor window. The Restaurant zum Jakobsbrunnen has been rebranded with a modern sign and an extension: 'Chez Leo' and has become a popular fondue restaurant. In house No. 12, where once was the Restaurant zur Laterne there is now the Tam-Tam, 'Tom-Tom' bar. Büchner's memorial inscription has been replaced by a plaque. Image: Photographer Heinrich Wolf-Bender. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

Another image from 1967 showing the Tam-Tam bar, Büchner's memorial and the Restaurant zum Jakobsbrunnen Image: Photographer Heinrich Wolf-Bender. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

Some images of the Café/Hotel Zähringerhof

Whilst no one would argue for the preservation of the insanitary, stinking and noisy hovels of the Spiegelgasse, the fate of the Café Zähringerhof is just one of the many examples of the serious errors of the Zurich town planners in the 1950s and 1960s.

Lenin's travelling band and their well-wishers may – may – have met up here in the Café-Restaurant Zähringer, on the corner of Zähringerstrasse and Mühlegasse, on the day of their departure. This is a photograph from 1900. It allows us to clarify our terminology: According to the signs on and above the doors of the premises at the front of the photograph, the building houses the Café-Restaurant Zähringer. The other possible location for Lenin's farewell meeting can be seen just behind the man standing on the left: it is, also according to the map, the Hotel Zähringerhof, a name which is confirmed by the letters beginning the signboard: 'HO…'. The texts on our map and in the article have been changed accordingly– which is a relief, since it is worryingly improbable that two businesses with Zähringerhof in their titles would be located so close to each other. The name Zähringerhof is more suitable for a hotel. We note the fine clock, the statues in the alcoves and the careful detail of the stonework. Image: Baugeschichtliches Archiv. 1900. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

By 1946 the café-restaurant seems to have gone out of business. A rather poor mural had replaced some of the features of the facade. The building was never used as a hotel but for office accommodation, possibly apartments. Where once the Hotel Zähringerhof could be glimpsed in the background on the left, we now see the Baumandl Künstzinngiesserei, 'art pewter foundry'. Image: Baugeschichtliches Archiv. 1946. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

By 2003 the building had been rebuilt and had become the Hotel Scheuble, on the way losing the rest of its statues, the clock and all the modelling on the facades. An interesting building was transformed into an architectural nonentity. Image: Baugeschichtliches Archiv. 2003. [Click to display a large version of this image in a new tab.]

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!