The total stress of Tom Bombadil

Richard Law, UTC 2017-07-01 09:44

Picking up the pieces

The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien's trilogy, is arguably one of the greatest literary creations of the 20th century. Some love it, some hate it, but all reasonable critics must acknowledge its innovative ambition. It was written in stages over 12 years, between 1937 and 1949, and published between 1954 and 1955.

Starting in 2001 each of the three books was run over by a cinematic steamroller in quick succession – Peter Jackson's three films.

Writing that is not to diminish Jackson's films. They are magnificent products, works of complex art in themselves. We have to accept that there is no scope for the nuance and subtlety of the written word; the massive immediacy of the films can never be true reflections of the books. My only regret is the inexplicable casting of an actor with disconcerting eyes and a strange, flat, expressionless face to play Frodo. Never mind – mustn't grumble.

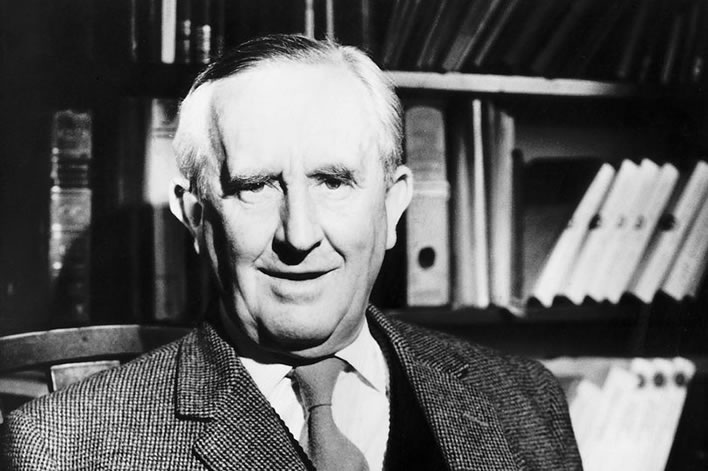

J.R.R. Tolkien, ND. Image: Birmingham Mail.

Now the steamrollers have trundled past we can pick Tolkien's crushed literary work up off the road and wonder what we can salvage. Those who read the books after having watched the films will never be able to free themselves from their massively dominant imagery – the imprint of those steamrollers.

As we scratch around the remains, however, we find a block of 30 pages in Book I that has been left undamaged, containing the three chapters in which the character of Tom Bombadil makes an appearance: 'The Old Forest', 'In the House Of Tom Bombadil' and 'Fog on the Barrow-Downs'.

Tom Bombadil, the great survivor

Now-decrepit hippies will recall Tom Bombadil with great fondness. He was Gaia before anyone had heard about Gaia. He had immense powers that he used only for good, unlike the military-industrial complex with that Vietnam thing. Tom B was utterly Zen. Moviegoers who haven't read the books, on the other hand, will have no idea who this character is.

For those who have not read 'The Fellowship of the Ring' here's a brief synopsis of the Bombadil episode. At this point in the story the 'ringbearer' Frodo and his three companions, Merry, Pippin and Sam have been seized by Old Man Willow while attempting to pass through the Old Forest. Merry and Pippin have both been imprisoned by the tree inside its great trunk. At this critical point Tom Bombadil – the 'Master' – turns up by chance and forces the tree to free them.

Tom invites the party to his house in the forest, where they spend two nights in the care of Tom and his lady, Goldberry. Shortly after leaving the house to continue their journey with the ring they are captured by wights on the Barrow-Downs. The hobbits summon Tom, who frees them and accompanies them to the borders of his territory.

The director of the films, Peter Jackson, was quite right to exclude the Tom Bombadil character from his film version. There is no violence in Tom – his great powers are effected by singing and chanting. He has no place in an action movie filled with pursuits and battles. The encounter between the hobbits and Tom and Goldberry has no bearing on the greater theme of the journey of the fellowship to Mount Doom to destroy the ring.

Thank you, Sir! – skipping over the Bombadil section kept it out of the way of the cinematic steamrollers that would run over the rest of the work and preserved this charming episode for readers of the book.

Tom Bombadil in the book

The survival of the section is particularly fortunate because Tolkien's realisation of the characters of Tom Bombadil and Goldberry, despite seemingly standing aside from the main plot line, is a fine literary achievement, quite equal to anything else in the trilogy.

The sweep of the trilogy as a whole is astonishing and was handled well by Tolkien. That said, however, modern readers probably find the prose of the historical and battle scenes – the main components of the films – irritatingly Wardour Street and the courtly doings even more so. This is not really Tolkien's fault: he was writing in a different age (1937-1949) and himself had come from an age before that (1892-1973).

In contrast, the prose of the Tom Bombadil section is timeless and quite remarkable. Tolkien, the Oxford Professor of Anglo-Saxon, reached back into the archaic treasures in his head and gave Bombadil and Goldberry, themselves ancient, mysterious spirits from an incomprehensible foretime, a language that was distant to modern readers, too.

Although out of place in the action movies, the Tom Bombadil section is of great importance to the book. At that moment in the narrative Tolkien is moving his hobbits from the settled rural ways of their home in the Shire into a world of mysterious, titanic, supernatural forces, populated by strange beings quite outside the ken of the rustics back home.

The Tom Bombadil section is an important step in that progression, a transition episode on the route to the full-blown mythology which the rustic hobbits will finally encounter in the Council of Elrond in the Elven halls of Rivendell.

Tom and Goldberry's origin is mysterious, their roles equally so. In their presence we are moved beyond the quotidian to become aware of other planes of being. In Bombadil's house, Frodo may make himself invisible, but Tom can see him, just as on the Barrow Downs he can look at an ancient shoulder-clasp and know of the woman who wore it, almost in a contemporaneous vision. Bombadil overlaps time and place. He embodies great powers, lightly worn.

He is also the hobbits' introduction to the good powers in the world. Up to that point they have been exposed only to the bad: their first encounter with the Dark Riders at the ford, the malignancy of the Old Forest and the old, evil-hearted willow who dominates it. Even Gandalf's importance as an agent of good they still do not yet appreciate fully. Until they meet Tom Bombadil, the general hobbit prejudice has been confirmed: outside the rural comfort of the Shire there is only danger and evil.

Tom Bombadil's 'true' nature, however, is never revealed: there must be mysteries, if the reader's imagination is to take flight. Mysteries inspire the reader but irritate the moviegoer – another good reason to drop this episode from the films.

Therefore let us not get involved in who or what the pair are or were, their exact ontological status; let's not worry about from whence Tolkien got the idea for them, or all the aetiological puzzlings that fill the message boards of the many Lord of the Rings fansites there are. Let us instead just look at the Bombadil passages as literary products.

Beowulf speaking

Innocents reading the words of Tom Bombadil will find themselves frequently stumbling. Passages which are written like prose seem to have strange convolutions, speech inversions, even the occasional internal rhyme. They cannot be verse though, because they are laid out as prose. Where there is verse in the text, it is laid out recognisably as verse. If readers try reading Tom's prose speech as verse the scansion fails within the space of a few phrases: His speech hints that it is not prose, but it doesn't seem to be poetry, either.

Let's leave the sections of obviously embedded poetry to one side for the moment. What is most interesting about the character of Tom Bombadil is the way that Tolkien used the techniques of Anglo-Saxon poetry in creating his speech. The seeming prose of Bombadil's speech that the reader finds on the page is not prose, but poetry – an adapted Anglo-Saxon poetry, which is why it is so tricky to read in the way we would read modern poetry.

The reader groans, sensing what is about to happen: an online edition of that bestseller, Anglo-Saxon Verse for Dummies. Have patience, it will be quick.

Firstly we have to realise that the first scribes of Anglo-Saxon poetry did not use metrical line-breaks. They wrote poetry in lines that only broke when they reached the edge of the page. Once we accept this fact our way is clear to accept Bombadil's line-break-free speech as a variety of Anglo-Saxon poetry.

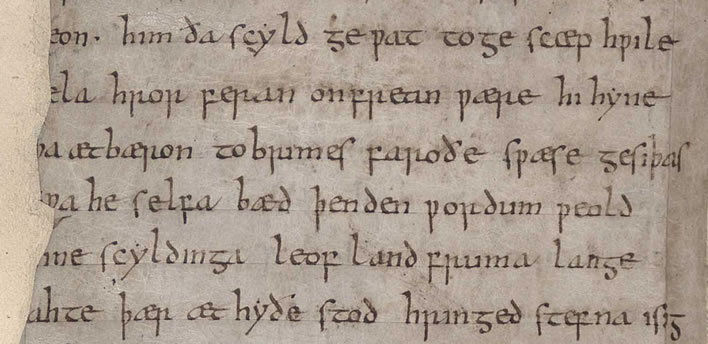

The funeral of Scyld Schefing. Folio 132v of the British Library manuscript of Beowulf (detail), ll. 26-31. The text of this passage is written out in our example below, beginning on the first line at the word 'him' and ending on the sixth line with the word 'ahte'.

Later poetry in English, influenced by Greek, Latin, Italian and French models, took up counting syllables and 'feet' (hence 'podic' metre), meaning that line-breaks effectively became metrical punctuation marks. Ask a non-specialist what the difference is between poetry and prose and he or she will probably tell you something to the effect that poetry is written in short lines which usually end in rhyme words.

In Anglo-Saxon poetry, however, syllables are not counted, only stresses. Since the verse is not bound to a fixed number of feet in each line (hexameters etc.) line-breaks have a much reduced importance.

In modern English verse we hover between stressed and podic metre, having largely merged the two. Typographic line-breaks are usual but not always necessary. We can read the classical-scholar/poet Milton's blank verse in a flat monotone and still get it, line breaks or no line breaks:

OF Mans First Disobedience, and the Fruit Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal tast Brought Death into the World, and all our woe, With loss of Eden, till one greater Man Restore us, and regain the blissful Seat, Sing Heav'nly Muse[…]

John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book 1, 1674, ll. 1-6. Online. We note in passing and say no more about it that the blind Milton dictated Paradise Lost, making it as much an oral poem as Beowulf or the Homeric epics.

We can read the classical-scholar/poet Swinburne and find ourselves springing along from strees to stress, line breaks or no line breaks:

In a coign of the cliff between lowland and highland, At the sea-down's edge between windward and lee, Walled round with rocks as an inland island, The ghost of a garden fronts the sea.

Algernon Charles Swinburne, 'A Forsaken Garden', in Poems and Ballads, Second Series, London, 1878, p. 27, ll. 1-4.

We can read the classical-scholar/poet Gerard Manley Hopkins' attempt at what he called 'sprung rhythm', a technique deeply influenced by Anglo-Saxon, and find ourselves also moving along, line breaks or no line breaks:

I caught this morning morning's minion, kingdom of daylight's dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing, As a skate's heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding Stirred for a bird, – the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

Gerard Manley Hopkins, 'The Windhover' (1877), in Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins, 1918, 'Poems 77', p. 29. Hopkins has brought us close to Anglo-Saxon and close to the speech of Tom Bombadil, too.

In any Anglo-Saxon line there can be somewhere between eight and twenty syllables. What matters, however, is not the number of syllables but the number of stresses. As a rule, each line has four main stresses and is divided into two half-lines, each as a rule with two stresses. Between the two half-lines is a distinct break, which some call a 'caesura'. Unsurprisingly, sentences often start after the break (or end at the break, whichever you prefer).

Caesura is really a term from podic metrics, as we might infer from its 16th century Latin origin: caedere, to cut. This is no bardic word. For a relatively modern example of the caesura in action we only need to listen to Pink Floyd's 1979 track 'Another Brick in the Wall', in which one or more beats are skipped:

Hey, teachers! | Leave them kids alone.

All in all it's just a | nother brick in the wall.

In Hrothgar's mead hall in Beowulf

Enough abstraction! Here is an example of how the Anglo-Saxon bards did it, the first six lines of the magnificent account of the boat funeral of Scyld Schefing, ll. 26-31 from the 'Prologue' to Beowulf. We reproduced the manuscript of this section above.

Don't worry about the meaning at the moment – if you roll over any of the highlights you will get a tooltip with the translation of the respective line. Concentrate on the structure, which we have broken down with line-breaks into lines, as is now usual in Anglo-Saxon texts. The half-line break is represented by a vertical bar (|). Our outrageous squandering of expensive parchment would have certainly shocked the two scribes who wrote the Beowulf manuscript. Bear in mind that there are as many interpretations of stressing as there as Anglo-Saxon experts. This is ours, there are certainly others.

Him ða Scyld gewat | to gescæp-hwile,

fela-hror feran | on Frean wære.

Hi hyne þa ætbæron | to brimes faroðe,

swæse gesiþas. | Swa he selfa bæd,

þenden wordum weold | wine Scyldinga,

leof land-fruma | lange ahte.

Text from C. L. Wrenn ed., W. F. Bolton, ed. Beowulf, Harrap, London, 1973. p. 98. For those wanting more, an excellent online place to begin is the Electronic Beowulf (University of Kentucky and the British Library).

The second major feature of Anglo-Saxon poetry is alliteration, which is also linked with the breaks and the half-lines. The chunks of speech that the half-lines and the breaks present are bound together by the similarities of sound that stretch across the break.

The general rule is that the initial sound of the first stressed syllable in the second half-line (the 'head-stave') sets the alliterative theme of the line. The stave alliterates with at least one of the stresses in the first half-line.

What do we mean by 'alliterates with'? Well, the best definition is so vague that it won't help you much: alliteration is some similarity between sounds. There are many qualifications about which sounds are similar and which not – for example, for the purposes of alliteration all vowels are considered to alliterate with each other.

This is not a course on Anglo-Saxon verse techniques, so we can leave that aside, particularly since it is obvious that the complex alliteration rules of Anglo-Saxon just cannot work well in English, if only because our words are now too French and our orthography bonkers. Each generation produces someone who attempts an English version of Beowulf in an Anglo-Saxon metrical style, but ultimately they all just sound odd.

We have to deal with one more point before we can turn with relief back to the friendly figure of Tom Bombadil. How did the Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford write Anglo-Saxon poetry in English? Let's let Tolkien himself tell us about what he understood to be the nature of Anglo-Saxon verse:

The very nature of Old English metre is often misjudged. In it there is no single rhythmic pattern progressing from the beginning of a line to the end, and repeated with variation in other lines. The lines do not go according to a tune. They are founded on a balance; an opposition between two halves of roughly equivalent phonetic weight, and significant content, which are more often rhythmically contrasted than similar. They are more like masonry than music.

From 'Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,' Sir Israel Gollancz Memorial Lecture, Proceedings of the British Academy, 1936, pp. 245-95. Reproduced in Beowulf - a verse translation, Seamus Heaney, ed. by Daniel Donoghue, Norton & Company, New York, 2002, p. 126.

The translation of Beowulf he himself produced in the early nineteen-twenties was one attempt of his to represent this masonry in English. He left that unpublished, so dissatisfied was he with it. Another attempt was in the Tom Bombadil section of The Lord of the Rings, which he wrote over a decade later (sometime before 1938).

It is possible to argue that, once the formal structure of alliteration has gone, there is no longer any reason to keep the line split into two half-lines by a break, because we have lost the glue that holds the half-lines together. Nevertheless, when we look at what Tolkien actually did in the Tom Bombadil episode in order to realise his English version of Anglo-Saxon verse, we shall see how cleverly he used the possibilities of opposition, extension and balance that line-splitting offers. Tolkien's remarks on the nature of Anglo-Saxon verse are very important for us – they are our key to unlocking what he did in the Tom Bombadil episode.

Tom Bombadil certainly speaks in a stress metre. Over short distances the metre looks as though it could be podic, more specifically iambic, but sooner or later the expected syllables are not there, or there are too many of them.

But not only is a systematic alliteration out of the question, the traditional Anglo-Saxon stress counting fails us, too. There is no way we can break up the running text of Tom Bombadil's speech into regular patterns of half-lines each containing two stresses. The stress types of half-line in Beowulf identified in Tolkein's classic analysis 'On translating Beowulf' are simply not applicable: Tolkien is writing in English, not Anglo-Saxon. Instead let's just map the stresses that are there in lines with lengths that reflect the punctuation of the text. The proof of the pudding is in the eating.

Bombadil speaking

Here we go. These are the speeches of Tom Bombadil freed from all other narrative. The stressed syllables are highlighted in green. Purists might split up the lines even further: where there are four stresses in a half-line it would be possible to produce two traditional two-stress half-lines. However, this brings no poetic advantage –for most of the time in our representation the line break at least corresponds with some real break, whether of punctuation or grammar, or the type of opposition or contrast that Tolkien told us about.

Declaim the text aloud like a bard. A goblet of mead now and again will help no end. Five will work wonders; ten will turn your performance into an internal monologue.

The source is J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, Part I, The Fellowship of the Ring, George Allen and Unwin Ltd. London, 2nd edition, 1966, p. 131-159.

[Frodo, the 'ringbearer' and his three hobbit companions, Sam, Merry and Pippin, are journeying from the Shire to Rivendell to attend the Council of Elrond. The group makes a detour through the Old Forest. Merry and Pippin are captured inside the trunk of the Old Willow. Frodo and Sam are trying to free them. Frodo shouts for help and soon Tom Bombadil arrives on the scene.]

Now, my little fellows, | where be you a-going to,

puffing like a bellows? | What's the matter here then?

Do you know who I am? | I'm Tom Bombadil.

Tell me what's your trouble! | Tom's in a hurry now.

Don't you crush my lilies!

fellows-bellows: there are a number of haphazard internal rhymes like this throughout the Tom Bombadil section. Their is no rhyme scheme behind them, it's just Tolkien having a bit of fun.

A few moments' reflection will show that Tom's utterance is not in podic metre. This first section contains three stresses in each half-line, but as we shall see this regularity does not last long. The stub half-line at the close of the utterance will be used a number of times as a terminator, almost in the manner of sapphics.

Unlike podic verse, where the lines must match a predetermined scheme – that is, they scan or they don't – stress-cadence metre is much more flexible. The stress markup here is a personal opinion. If, bard, you prefer something different, seize your lyre and off you go.

Old Man Willow? | Naught worse than that, eh?

That can soon be mended. | I know the tune for him.

Old grey Willow-man! | I'll freeze his marrow cold,

if he don't behave himself. | I'll sing his roots off.

I'll sing a wind up | and blow leaf and branch away.

Old Man Willow!

Yet another stub half-line as a terminator.

[Tom sings to the willow, forcing it to release Merry and Pippin. Tolkien doesn't reproduce Tom's song to the willow – spells of power should be kept to oneself. He invites them back to his house.]

Well, my little fellows! | You shall come home with me!

The table is all laden | with yellow cream, honeycomb,

and white bread and butter. | Goldberry is waiting.

Time enough for questions | around the supper table.

You follow after me | as quick as you are able!

table-able: another erratic rhyme.

So far we have become used to finding a stress on the first syllable of each line. Lines 2 and 3 here show that this does not necessarily have to be the case.

[The hobbits have now arrived at Tom Bombadil's house.]

Here's my pretty lady! | Here's my Goldberry

clothed all in silver-green | with flowers in her girdle!

Is the table laden? | I see yellow cream and honeycomb,

and white bread, and butter; | milk, cheese, and green herbs

and ripe berries gathered. | Is that enough for us?

Is the supper ready?

The repetition of the list of foodstuffs from the preceding verse, with slight changes and extensions, is not laziness, it is a fine use of a text 'formula' – a feature that is so characteristic of oral poetry, whether by that of our Anglo-Saxon bards or Homeric bards.

The break between half-lines allows the use of very short questions and other statements that would be difficult to construct in podic metre: Here's my pretty lady! Is that enough for us? Is the supper ready?

[The hobbits have now arrived at Tom Bombadil's house. Goldberry reminds Tom of his duties as a host, to which he responds:]

Tom, Tom! your guests are tired, | and you had near forgotten!

Come now, my merry friends, | and Tom will refresh you!

You shall clean grimy hands, | and wash your weary faces;

cast off your muddy cloaks | and comb out your tangles!

[Frodo asks Tom how he happened across them in their moment of danger. Tom responds:]

Did I hear you calling?

Nay, I did not hear: | I was busy singing.

Just chance brought me then, | if chance you call it.

It was no plan of mine, | though I was waiting for you.

We heard news of you, | and learned that you were wandering.

We guessed you'd come ere long | down to the water:

all paths lead that way, | down to Withywindle.

Old Grey Willow-man, | he's a mighty singer;

and it's hard for little folk | to escape his cunning mazes.

But Tom had an errand there, | that he dared not hinder.

That is right! | Now is the time for resting.

Some things are ill to hear | when the world's in shadow.

Sleep till the morning-light, | rest on the pillow!

Heed no nightly noise! | Fear no grey willow!

pillow-willow: rhyme. Not appropriate here, but interested readers might take some time to investigate the long tradition of singing spells and incantations as a powerful, magical art, the willow tree being a 'mighty singer' with hypnotic powers. The singing willow of the Old Forest seems to be a step on the way to what would become Treebeard and the Ents, who first appear in The Two Towers, volume II of the trilogy.

[It is the following morning. The hobbits wake up in Tom's house. Tom was up much earlier:]

I have been walking wide, | leaping on the hill-tops,

since the grey dawn began, | nosing wind and weather,

wet grass underfoot, | wet sky above me.

I wakened Goldberry | singing under window;

but nought wakes hobbit-folk | in the early morning.

In the night little folk | wake up in the darkness,

and sleep after light has come! | Ring a ding dillo!

Wake now, my merry friends! | Forget the nightly noises!

Ring a ding dillo del! | derry del, my hearties!

If you come soon | you'll find breakfast on the table.

If you come late | you'll get grass and rain-water!

Our stress mapping of the last two lines is not convincing, but those lines do show the capability of stress-cadences to handle diverse speech acts. Tolkien's idea of opposition between half-lines can be clearly seen here.

This is Goldberry's washing day, | and her autumn cleaning.

Too wet for hobbit-folk | — let them rest while they are able!

It's a good day for long tales, | for questions and for answers,

so Tom will start the talking.

[The hobbits listen to Tom's 'long tales'. The tales are not told in direct speech but the gist of them is reported to us by Tolkien. This could be a scene in an Anglo-Saxon mead-hall, (just like the one described in Beowulf, that is attacked by the monster Grendel).

Where nowadays people have an evening meal and then slump in front of the TV, after an Anglo-Saxon feast the sated participants settled down to listen to their bard – which is just what the hobbits do in Tom's house after breakfast. The bard's tales would encompass all the legends and historical accounts which Tolkien lists in his description of Tom Bombadil's bardic performance.

It is a pity that Tolkien chose not to use Tom Bombadil to retail the history of Middle-Earth in his later works, just as he had retailed it to the hobbits. There is, however, probably a limit to how much stress-cadence verse that even a Professor of Anglo-Saxon wants to write. At the end of Tom's tales the hobbits ask him to tell them who he is. He responds:]

Don't you know my name yet? | That's the only answer.

Tell me, who are you, | alone, yourself and nameless?

But you are young and I am old. | Eldest, that's what I am.

Mark my words, my friends:

Tom was here before | the river and the trees;

Tom remembers | the first raindrop and the first acorn.

He made paths before the Big People, | and saw the little People arriving.

He was here before the Kings | and the graves and the Barrow-wights.

When the Elves passed westward, | Tom was here already, before the seas were bent.

He knew the dark under the stars | when it was fearless —

before the Dark Lord | came from Outside.

The stressing given here for When the Elves passed westward, | Tom was here already, before the seas were bent. seems to work, but is difficult to rationalise. Tom's words are a good justification for our invention of the term 'stress-cadence'.

And let us have food and drink! | Long tales are thirsty.

And long listening's hungry work, | morning, noon, and evening!

A fine example of very successful stress-cadences that fail to conform to a standard metrical pattern.

[Tom gives us his opinion of Farmer Maggot, who sheltered the travellers on an earlier part of their journey.]

There's earth under his old feet, | and clay on his fingers;

wisdom in his bones, | and both his eyes are open,

[Tom asks Frodo to show him the One Ring. It has no effect on Tom: not only does he not disappear when he puts it on, he makes the ring itself disappear and reappear. When he gives the ring back, Frodo wants to make sure that it really is his ring that Tom handed back. He slips it on and becomes invisible to his companions – but Tom can still see him.]

Hey there! Hey! | Come Frodo, there!

Where be you a-going?

Old Tom Bombadil's | not as blind as that yet.

Take off your golden ring! | Your hand's more fair without it.

Come back! Leave your game | and sit down beside me!

We must talk a while more, | and think about the morning.

Tom must teach the right road, | and keep your feet from wandering.

[The hobbits are departing. Tom is giving them advice on the route to take.]

Keep to the green grass. | Don't you go a-meddling

with old stone or cold Wights | or prying in their houses,

unless you be strong folk | with hearts that never falter!

[After they have left the house, Frodo realises that they have not said goodbye to Goldberry. The following words are not those of Tom but of Frodo, showing that the hobbit has started to adopt Tom's way of speaking.]

Goldberry! My fair lady, | clad all in silver green!

We have never said farewell to her, | nor seen her since the evening!

[Some hours after leaving Tom's house the hobbits are trapped in a burial chamber by a barrow-wight. In desperation, Frodo recites the verse that Tom taught him to use if they needed his help. Tom arrives and chants a spell to drive the wight out, a spell which we can read, unlike the song used against Old Man Willow:]

Get out, you old Wight! | Vanish in the sunlight!

Shrivel like the cold mist, | like the winds go wailing,

Out into the barren lands | far beyond the mountains!

Come never here again! | Leave your barrow empty!

Lost and forgotten be, | darker than the darkness,

Where gates stand for ever shut, | till the world is mended.

Tom's chant is also printed as embedded stress-cadence verse. There is, however, a common structure between the two groups of three lines and the stressing is a much more regular 4|3 pattern.

Burial mounds, 'barrows', at Gamla Uppsala, 'Old Uppsala', in Sweden. Image: ©Wiglaf.

We briefly touched on the Viking fear of the spirits of the dead and their methods to keep their dwellings free of them. How much more dangerous, then, were the barrows themselves.

[Tom drives out the wight and frees the hobbits from the barrow. This is another of Tom's chants, this time to revive the hobbits.]

Wake now my merry lads! | Wake and hear me calling!

Warm now be heart and limb! | The cold stone is fallen;

Dark door is standing wide; | dead hand is broken.

Night under Night is flown, | and the Gate is open!

Tom's chant is printed as embedded verse, also with a 4|3 stress pattern. Note the 'nearly rhymes' at the end of the lines: {a-i}{a-e}{o-e}{o-e}.

[The hobbits wake up from the barrow-wight's spell. They find they have been dressed in clothes from the barrow, an act that represents magical substitution with the spirits of their former wearers.]

You've found yourselves again, | out of the deep water.

Clothes are but little loss, | if you escape from drowning.

Be glad, | my merry friends,

and let the warm sunlight | heat now heart and limb!

Cast off these cold rags! | Run naked on the grass,

while Tom goes a-hunting!'

[Tom returns with the group's ponies.]

Here are your ponies, now! | They've more sense (in some ways)

than you wandering hobbits have | — more sense in their noses.

For they sniff danger ahead | which you walk right into;

and if they run to save themselves, | then they run the right way.

You must forgive them all; | for though their hearts are faithful,

to face fear of Barrow-wights | is not what they were made for.

See, here they come again, | bringing all their burdens!'

Some uncertainty in assigning the stress in the first four lines of this section. The weak and pointless parenthetical '(in some ways)' appears to be there for some metrical reason, but that reason is obscure.

He's mine, my four-legged friend; | though I seldom ride him,

and he wanders often far, | free upon the hillsides.

When your ponies stayed with me, | they got to know my Lumpkin;

and they smelt him in the night, | and quickly ran to meet him.

I thought he'd look for them | and with his words of wisdom

take all their fear away.

But now, my jolly Lumpkin, | old Tom's going to ride.

Hey! he's coming with you, | just to set you on the road;

so he needs a pony.

For you cannot easily talk | to hobbits that are riding,

when you're on your own legs | trying to trot beside them.

[The hobbits leave the barrow grounds.]

I've got things to do, | my making and my singing,

my talking and my walking, | and my watching of the country.

Tom can't be always near | to open doors and willow-cracks.

Tom has his house to mind, | and Goldberry is waiting.[…]

Here is a pretty toy | for Tom and for his lady!

Fair was she who long ago | wore this on her shoulder.

Goldberry shall wear it now, | and we will not forget her![…]

Old knives are long enough | as swords for hobbit-people,

Sharp blades are good to have, | if Shire-folk go walking,

east, south, or far away | into dark and danger.[…]

Few now remember them | yet still some go wandering,

sons of forgotten kings | walking in loneliness,

guarding from evil things | folk that are heedless.

Some gentle rhyming: loneliness-heedless and kings-things. The ellipses mark short pieces of narrative text. The whole section is a masterful piece of writing – was Tolkien's skill with stress-cadence verse getting better as the wrote his way through the episode?

[At the border of his territory, Tom and the group make their final parting.]

No, I hope not tonight | nor perhaps the next day.

But do not trust my guess; | for I cannot tell for certain.

Out east my knowledge fails.

Tom is not master of Riders | from the Black Land

far beyond his country

Stress-cadence writing that manages to express complex uncertainty.

Tom will give you good advice, | till this day is over

(after that your own luck | must go with you and guide you):

four miles along the Road | you'll come upon a village,

Bree under Bree-hill, | with doors looking westward.

There you'll find an old inn | that is called The Prancing Pony.

Barliman Butterbur | is the worthy keeper.

There you can stay the night, | and afterwards the morning

will speed you upon your way.

Be bold, but wary! | Keep up your merry hearts,

and ride to meet your fortune!

[Tom's final words to them are printed as embedded poetry.]

Tom's country ends here: | he will not pass the borders.

Tom has his house to mind, | and Goldberry is waiting!

There now, that was much more fun than watching the film, wasn't it?

Wasn't it?

Ending the tale

One day, we hope, an enterprising publisher may bring out an edition of The Lord of the Rings with Tom Bombadil's utterances properly stress-marked, thus making the task of the reader much easier. It would not be a surprise if somewhere in Tolkien's papers there was a version of those utterances with little pencil ticks over the stressed syllables, perhaps even caesura marks to separate the half-lines. Even professors of Anglo-Saxon need the odd pencil mark from time to time. Who knows? Everything is a mystery, these days.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!