And is there honey still for tea?

Richard Law, UTC 2017-08-07 10:28

Fresh from raising Ernest Dowson's shade for the 150th anniversary of his birth on 2 August, another poet's ghost claims our necromancy on 4 August, the 130th anniversary of his birth: Rupert Brooke (1887-1915).

Whereas Dowson is all childish surface, his outlines blurred with drunken self-destruction, Brooke is a much more complex character who played complex roles in a large and complex circle of important friends. He also had early success and esteem that overflowed into adoration, male and female.

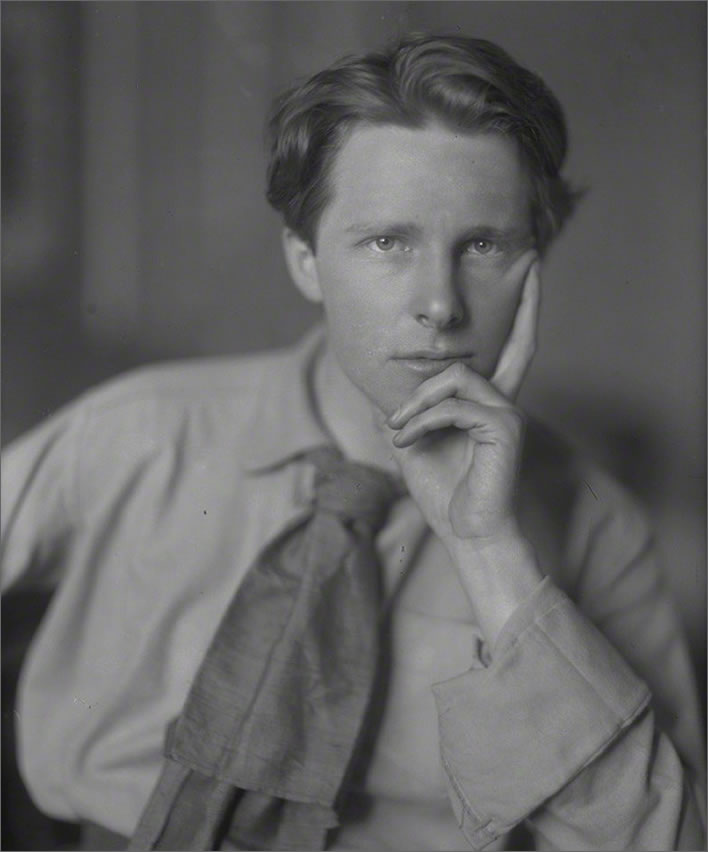

Rupert Brooke, photographed in April 1913 by Sherrill Schell (1877–1964), an American photographer (m) living in London. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

He became one of the leading English voices of that strange time between 1910 and 1914. In Germany writers were longing for war, in the sense of longing for something – anything – to happen. Writers in Britain were doing much the same, though slightly less hysterically. Brooke, for his part, wrote nothing overtly political but much that was nationalistic and patriotic – nothing wrong in that – with a focus on feeling and emotion. By the end of this period, particularly after his return from his visits to Germany, Brooke had become violently anti-German. Brooke saw war coming, as did so many, and thought in the end that he might as well get involved in what he saw would be the defining moment of his lifetime.

Four years of military-industrial apocalypse would change all their tunes and give birth to the new factual realism of 'War Poets' such as Owen and Sassoon, then after them the 'Modernists'. The feelings and emotions, the nobility of mind of the pre-war writers was wiped away by the intrusion of reality: the shrapnel of the bursting shells, the bullets of the machine guns, the dysentery, rotting flesh, blindness and amputations cared nothing for feelings and emotions – they were visited equally upon the noble and the mean, the hero and the coward, the just and the unjust.

He had no chance to become either a war hero or a war poet. In September 1914, using his connections, he was given a commission in the Royal Naval Division. In October he was present during the futile action to relieve Antwerp from the German siege. There followed four months of inaction until 28 February the following year, when he was sent off on what would become the disastrous Gallipoli campaign.

He never made it: on 20 April he developed sepsis from – it is said – a mosquito bite on his lip. He was moved to the French hospital ship moored off the Greek island of Skyros on 22 April. The ship was empty apart from him – it was waiting there for the meat grinder of the Gallipoli campaign to get going and fill it up. He died in the afternoon of 23 April, the day on which the landings were due to start, and was buried on Skyros that night.

He had a quiet death, if there can be such a thing, ending in the final romance of a burial in 'some corner of a foreign field', fully in accordance with his sonnet The Soldier (1914):

V. The Soldier

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there's some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England's, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

That sonnet had become one of the anthems of the warmongers of Britain. As it happens, Brooke's poetic monstrosity had been read out barely three weeks before the poet's death by the Dean of St Paul's Cathedral as part of his Easter Sunday sermon.

Brooke never became a war poet because he saw no war, certainly not the sort of war that killed his brother in France in June of that year. He never wrote about war either: the vapid rhetoric of The Soldier is not about war at all; remove the word 'soldier' from the title and all relationship to war has gone. It is a poem for the bereaved: the grieving widows, the mothers and fathers and siblings, or for those who would send it to them as comfort. Worse, it is a poem to remind the doomed themselves of the glorious end awaiting them.

That sermon was the high point of Brooke's reputation, which continued afloat on patriotism throughout the war. By 1918 the collection that contained that poem, 1914, had gone through 24 impressions. But soon thereafter a time came when that poem – Brooke at his affected worst – even the very memory of its popularity, would leave a bad taste in the speaker's mouth. No English churchman would ever read that out in a sermon nowadays, least of all, Wimpy Welby.

We can measure the degree of that rejection: only 20 years after Brooke's death, when W. B. Yeats was compiling his – admittedly idiosyncratic – poetry anthology, The Oxford Book of Modern Verse 1892-1935 (1936), Brooke was represented by only one poem, Clouds, out of a total of nearly 400 poems from that 40 year period. How are the mighty fallen!

'The handsomest man in England'*. No, not him, the one on the right, idiot. The one on the left is Duncan Campbell Scott (1862-1947), the Canadian writer, the handsomest man in Canada. Taken in July 1913, they are sitting in a garden that would shock any visiting Prussian. Image: Unknown photographer, National Portrait Gallery, London.

*Traditionally ascribed to W.B. Yeats, but never with a verifiable source, as far as I know.

Brooke's memory still lingers in a few people, probably those who still cherish his 'Englishness'. Nevertheless, we can say that Rupert Brooke, in all but name, has been obliterated for all subsequent generations, apart from one hit phrase among the educated: 'And is there honey still for tea?'. A few people will also remember the line that goes before it: 'yet / Stands the Church clock at ten to three?'; even fewer will be able to say that these lines are from a poem called Grantchester (recte: The Old Vicarage, Grantchester); even fewer will remember that its author was Rupert Brooke; even fewer that it is very specifically dated '1912' and only a very, very tiny number will be able to quote any other lines from it.

Rupert Brooke, photographed in April 1913 by Sherrill Schell. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

Before the internet made all things available, it would be very unlikely that you would find 'Grantchester' in a modern anthology. The Oxford University Press anthology Modern Verse 1900-1950 from 1953, for example, has Grantchester (unabridged) and The Dead, but that would be largely the end of it for Brooke's poetical legacy.

So, to sate the shade we called up with Dowson, that he might descend once more and leave us in peace for at least another decade, let us look at The Old Vicarage, Grantchester. It will be a kinder memorial to the dead poet than The Soldier. And some of it, despite everything, is actually rather good – very good, in fact.

The Old Vicarage, Grantchester

(Cafe des Westens, Berlin, May 1912)

The Café des Westens, Kurfürstendamm 18 in Berlin-Charlottenburg, was a centre of intellectual – particularly bohemian – life in Berlin during the prewar period.

Just now the lilac is in bloom,

All before my little room;

'all before': is simple poetic incompetence. The common use of 'before' is as a temporal adverb, so since it follows the temporal phrase 'Just now' that is how we read it. When we get to 'little room' our brains realise their mistake and reprogram the meaning of 'before' to mean the spatial 'in front of'.

'my little room': might be interpreted as modest plainness – but really it just sounds twee.

And in my flower-beds, I think,

Smile the carnation and the pink;

And down the borders, well I know,

The poppy and the pansy blow…

More linguistic incompetence: the reader's brain has to make a lot of adjustments in these lines to keep to the temporal scheme that Brooke established in the first line with 'Just now'. The simplest way to explain this is to rewrite the passage as good grammar (if bad poetry):

And in my flower-beds, I think,

Are smiling the carnation and the pink;

And down the borders, well I know,

The poppy and the pansy are blowing…

We meet here the first example of Brooke's bizarre use of the ellipsis '…' that so disfigures this poem. The ellipsis indicates that some text is missing or has been broken off; it is not a soft full stop. Brooke uses the mark frequently but usually wrongly, as here, following 'The poppy and the pansy blow': nothing is missing or interrupted at this point, the reverie continues on the next line. Using it here is not harmless: it makes the 'Oh!' that follows it sound like an interruption to the daydream, when it is simply a continuation.

Oh! there the chestnuts, summer through,

Beside the river make for you

A tunnel of green gloom, and sleep

Deeply above; and green and deep

The stream mysterious glides beneath,

Green as a dream and deep as death.

Even after repeating this passage several times the reader still stumbles at the oddities of its syntax. Its helps if we get rid of the 'Oxford comma' after 'gloom' and use a hearty full stop instead of the semi-colon after 'above', which is required because the object of our attention has changed from the chestnuts to the stream:

Oh! there the chestnuts, summer through,

Beside the river make for you

A tunnel of green gloom and sleep

Deeply above. And green and deep

The stream mysterious glides beneath,

Green as a dream and deep as death.

Separating 'the chestnuts' from their position 'Beside the river' with a disconnected temporal expression 'summer through' is not beautiful, but sometimes mediocre poets have to do things like that to get their rhymes.

'Green as a dream and deep as death' is an example of Brooke at his sentimental, mawkish worst: why dreams are green and death is as deep as this stream we are never told. Perhaps Brooke is having a psychotic episode (see below) – after the lilac in May, the flowering garden and the cool shade of the chestnuts he suddenly gives us green dreams and deep death. Never mind! the next few lines will bring us back.

— Oh, damn! I know it! and I know

How the May fields all golden show,

And when the day is young and sweet,

Gild gloriously the bare feet

That run to bathe…

The odd use of 'show' to mean 'appear' troubles the reader, as does another use of the simple present, here in 'all golden show', when we really need the present continuous 'golden are all showing' to relate that action to the moment expressed by 'Just now' at the beginning of the poem.

'the bare feet that run to bathe': skinny dipping was a hobby of Brooke and his circle. This is the kind of moral turpitude that comes from having independent means and too much time on your hands.

Du lieber Gott!

Here am I, sweating, sick, and hot,

And there the shadowed waters fresh

Lean up to embrace the naked flesh.

Du lieber Gott!: 'Oh, good God!'. This part-line, the loud exclamation of one of the noisy guests at the teeming Café des Westens, justifies the use of the ellipsis at the end of the preceding part-line: the daydream of England has been interrupted.

'Sweating, sick, and hot': Brooke was not only physically ill during his stay in Berlin, he was in the middle of a serious psychotic crisis, brought on, your author firmly believes, by the butterfly's association with the lunatics of the Bloomsbury Group. Grantchester was indeed written by a madman in the clinical sense.

Temperamentvoll German Jews

Drink beer around; — and there the dews

Are soft beneath a morn of gold.

Temperamentvoll, 'excitable, spirited'. Cultural life in Berlin at the time was a largely Jewish activity; The cool, reserved Englishman Brooke is sneering not just at excitable, noisy and beer-drinking Germans, but explicitly 'German Jews' in the Café des Westens. This sneer may be one of the reasons that the poem is no longer anthologised in polite circles. It expresses the widespread antisemitism of the time.

'Drink beer around' is an unpleasant contortion.

Changes in pronunciation over the last hundred years mean that the words 'Jews' and 'dews' no longer rhyme as closely as they did when Brooke was writing. The pair has now become one of those 'Cockney rhymes' that Brooke himself mocks later in this poem. Even in 1912 the rhyme was an over-clever affectation.

Here tulips bloom as they are told;

Unkempt about those hedges blows

An English unofficial rose;

And there the unregulated sun

Slopes down to rest when day is done,

And wakes a vague unpunctual star,

A slippered Hesper; and there are

Meads towards Haslingfield and Coton

Where das Betreten's not verboten.

A wonderful passage – one good thing after another: at last some poetry we can admire!

'an English unoffical rose', a clever allusion to Rosa officinalis, a rose which every Lancastrian knows (unfortunately now known as Rosa gallica, the 'French Rose').

'Hesper' is the planet Venus, in its role as the evening star. The quality of the writing allows us to accept an 'unregulated' sun and a 'vague unpunctual' star as poetic licence.

'Betreten verboten': 'keep off the grass'. Brooke is by no means the first to notice this Prussian talent for bossiness: the Berlin humourist Adolf Glassbrenner, visiting Bohemia in 1836, joked that there were as many devotional images in Bohemia as there were warning signs in Prussia.

εἴθε γενοίμην … would I were

In Grantchester, in Grantchester! —

'eithe genoimen'. [ei-the-gen-oi-men-would-I-were] gives the eight syllables of the line – an allusion by the son of a classics master at Rugby school to an epigram from the Greek Anthology ascribed to Plato (book 7, chapter 669) and addressed to a hot boy called Aster (star): 'My Aster, you are looking at the stars. Would that I were / the heavens, so that I could gaze on you with many eyes'. This epigram has been translated in a number of English works, in which the hot boy Aster becomes the hot chick Stella. Let's not go there. It does not take a scholar of Ancient Greek to point out that this allusion to Plato's longing adds nothing to the meaning of the poem and is simple affectation (in the same way that Dowson's Horatian Latin titles were affectation).

John Betjeman made a witty reference to Brooke's pretentious allusion in his delightful poem The Olympic Girl, wishing that he, the 'unhealthy worm' upon whom this tennis-playing goddess frowns down in contempt could be 'An object fit to claim her look', or even just be her racket 'press'd / With hard excitement to her breast'. Betjeman, by far the better poet, used Brooke's allusion to Plato's lusting epigram much more appropriately than Brooke himself did. Betjeman has the lightness of touch gently but mockingly to apologise to Brooke: 'Forgive me, shade of Rupert Brooke'. [From A Few Late Chrysanthemums (1954), in Collected Poems, John Murray, London, 1993, p. 186.]

Some, it may be, can get in touch

With Nature there, or Earth, or such.

And clever modern men have seen

A Faun a-peeping through the green,

And felt the Classics were not dead,

To glimpse a Naiad's reedy head,

Or hear the Goat-foot piping low:…

But these are things I do not know.

I only know that you may lie

Day long and watch the Cambridge sky,

And, flower-lulled in sleepy grass,

Hear the cool lapse of hours pass,

Until the centuries blend and blur

In Grantchester, in Grantchester….

This passage is an introduction to the appearance of the ghostly apparitions in the dream sequence that follows. It should be cut out: it has no merit whatsoever, being a confused and maudlin shambles.

Still in the dawnlit waters cool

His ghostly Lordship swims his pool,

And tries the strokes, essays the tricks,

Long learnt on Hellespont, or Styx.

'His ghostly Lordship' is George Gordon Lord Byron (1788-1842), who during his time at Cambridge (1805-1808) would swim frequently in the Cam/Granta. A pool close to the vicarage, where once the mill stood, is called Byron's Pool, hence Brooke's term 'his pool'. Byron was a strong swimmer and Brooke alludes to his feat of swimming across the Hellespont (in 1810). Since Byron's unorthodox lifestyle choices will surely have sent him to Hell – no doubt at all about that – Brooke suggests he may have been practising his swimming in the River Styx, the border between the world of the liiving and Hades. In 1811, one of Byron's friends at Cambridge, Charles Skinner Matthews (1785-1811), became tangled in the reeds of the Cam and drowned.

Dan Chaucer hears his river still

Chatter beneath a phantom mill.

'Dan Chaucer' is the name applied to Geoffrey Chaucer (c.1343-1400) by Edmund Spenser (c.1552-1599) in The Faerie Queene (Book IV, Canto II) 'Dan Chaucer, well of English vndefyled'. 'Dan' is a title of respect, equivalent to 'Sir' or 'Master'. Spenser went to Cambridge (1569-1576), but Chaucer was a Londoner. Chaucer's association with the 'phantom mill' is from the third story in the Canterbury Tales, 'The Reeve's Tale', which concerns the cuckoldry of the Cambridge miller, Symkyn. The mill is a phantom because it is no longer there – its replacement was some distance away. Chaucer's mill stood next to 'Byron's Pool', which, in fact, was the old mill pond. Brooke and his friends swam in the dam above the pool.

Tennyson notes, with studious eye,

How Cambridge waters hurry by…

Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-1892) was at Cambridge from 1827 to 1831, when he left without a degree on the death of his father. Brooke's allusion is to Tennyson's poem The Miller's Daughter, first published in 1833, then substantially revised and republished in 1842. Tennyson stated that the mill he had in mind in the poem was that at Grantchester/Trumpington. That 'Cambridge waters hurry by' appears to be a specific reference to:

I loved the brimming wave that swam

Thro' quiet meadows round the mill,

The sleepy pool above the dam,

The pool beneath it never still,

A few lines earlier Tennyson, like Brooke, remarks on the chestnut trees:

Or those three chestnuts near, that hung

In masses thick with milky cones.

This passage with its celebrity ghosts should be cut: it adds nothing to the poem as a whole. Whereas the rest of the poem is a largely allusion-free surface, the reader is suddenly confronted with eight dense lines concocted by a Cambridge English graduate that definitely smell of the lamp.

And in that garden, black and white,

Creep whispers through the grass all night;

And spectral dance, before the dawn,

A hundred Vicars down the lawn;

Curates, long dust, will come and go

On lissom, clerical, printless toe;

And oft between the boughs is seen

The sly shade of a Rural Dean…

Till, at a shiver in the skies,

Vanishing with Satanic cries,

The prim ecclesiastic rout

Leaves but a startled sleeper-out,

Grey heavens, the first bird's drowsy calls,

The falling house that never falls.

The entire 'ghostly vicarage' section above should also be cut: its silliness only serves to weaken the overall message of the poem, a message of homesickness and nostalgia established in the opening section. It could have been published on its own as a vignette of ghostly Grantchester.

God! I will pack, and take a train,

And get me to England once again!

For England's the one land, I know,

Where men with Splendid Hearts may go;

And Cambridgeshire, of all England,

The shire for Men who Understand;

And of that district I prefer

The lovely hamlet Grantchester.

For Cambridge people rarely smile,

Being urban, squat, and packed with guile;

And Royston men in the far South

Are black and fierce and strange of mouth;

At Over they fling oaths at one,

And worse than oaths at Trumpington,

And Ditton girls are mean and dirty,

And there's none in Harston under thirty,

And folks in Shelford and those parts

Have twisted lips and twisted hearts,

And Barton men make Cockney rhymes,

And Coton's full of nameless crimes,

And things are done you'd not believe

At Madingley on Christmas Eve.

Strong men have run for miles and miles,

When one from Cherry Hinton smiles;

Strong men have blanched, and shot their wives,

Rather than send them to St. Ives;

Strong men have cried like babes, bydam,

To hear what happened at Babraham.

But Grantchester! ah, Grantchester!

There's peace and holy quiet there,

Great clouds along pacific skies,

And men and women with straight eyes,

Lithe children lovelier than a dream,

A bosky wood, a slumbrous stream,

And little kindly winds that creep

Round twilight corners, half asleep.

In Grantchester their skins are white;

They bathe by day, they bathe by night;

The women there do all they ought;

The men observe the Rules of Thought.

They love the Good; they worship Truth;

They laugh uproariously in youth;

(And when they get to feeling old,

They up and shoot themselves, I'm told)…

The above section should be cut out completely – what is it doing here at all?

Ah God! to see the branches stir

Across the moon at Grantchester!

To smell the thrilling-sweet and rotten

Unforgettable, unforgotten

River-smell, and hear the breeze

Sobbing in the little trees.

Some excellent lines, really excellent, but ruined when Brooke goes full pathetic fallacy on us with the awful, mawkish, childish 'breeze / Sobbing in the little trees'. Such a pity, because from now on Brooke moves into masterpiece mode:

Say, do the elm-clumps greatly stand

Still guardians of that holy land?

The chestnuts shade, in reverend dream,

The yet unacademic stream?

'yet unacademic' because the stream has not reached Cambridge yet.

Is dawn a secret shy and cold

Anadyomene, silver-gold?

'Anadyomene', the epithet of Aphrodite arising from the sea foam, an epithet that occurs several times in the Greek Anthology, our source for εἴθε γενοίμην from Plato's 'Aster' epigram. The cold dawn rising up out of the North Sea off the East Anglian coast. Wonderful.

Sandro Botticelli (1445?-1510), Nascita di Venere, 'The Birth of Venus' (c. 1485). Image: Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Titian's effort, Venus Anadyomene (1520), a gigantic, pneumatic nude washing her hair next to an improbably tiny scallop, is third-rate daubing in comparison.

And sunset still a golden sea

From Haslingfield to Madingley?

And after, ere the night is born,

Do hares come out about the corn?

Oh, is the water sweet and cool,

Gentle and brown, above the pool?

And laughs the immortal river still

Under the mill, under the mill?

Say, is there Beauty yet to find?

And Certainty? and Quiet kind?

Deep meadows yet, for to forget

The lies, and truths, and pain? … oh! yet

Stands the Church clock at ten to three?

And is there honey still for tea?

A metrical and poetic tour de force. These wonderful, flowing lines were for many years among the most famous and quoted passages of poetry in the English language – and quite deservedly so.

The 'lies, and truths, and pain' that have to be forgotten are probably related to the catastrophe of his relationship with Katherine 'Ka' Laird Cox. The shambles and bitterness of that relationship, the jealousies and inconstancies within the free-rolling Bloomsbury group of artists and Brooke's increasingly fragile and paranoid mental state came to a head in 1912. Brooke wisely sought healing in distance: he toured the United States and the South Seas and, we are told, fathered a child in Tahiti. These travels occupied his mind for the next two years until 1914, when the war and a mosquito would take him away to those 'deep meadows' of forgetfulness from whence his shade appears to us today.

His patriotic, anti-German poem has moved through elegaic nostalgia and suddenly concludes with a terrible cry of anguish and loss. Will the real poem please stand up?

As our poet returns to the deep meadows from which we summoned him, let us create a fitting memorial: The Old Vicarage, Grantchester, compact and lightly tweaked edition – well worth learning by heart, even with a few blemishes.

The Old Vicarage, Grantchester (compact edition)

(Cafe des Westens, Berlin, May 1912)

Just now the lilac is in bloom,

All before my little room;

And in my flower-beds, I think,

Smile the carnation and the pink;

And down the borders, well I know,

The poppy and the pansy blow.

Oh! there the chestnuts, summer through,

Beside the river make for you

A tunnel of green gloom and sleep

Deeply above. And green and deep

The stream mysterious glides beneath,

Green as a dream and deep as death.

— Oh, damn! I know it! and I know

How the May fields all golden show,

And when the day is young and sweet,

Gild gloriously the bare feet

That run to bathe…

Du lieber Gott!

Here am I, sweating, sick, and hot,

And there the shadowed waters fresh

Lean up to embrace the naked flesh.

Temperamentvoll German Jews

Drink beer around; — and there the dews

Are soft beneath a morn of gold.

Here tulips bloom as they are told;

Unkempt about those hedges blows

An English unofficial rose;

And there the unregulated sun

Slopes down to rest when day is done,

And wakes a vague unpunctual star,

A slippered Hesper; and there are

Meads towards Haslingfield and Coton

Where das Betreten's not verboten.

Ah God! to see the branches stir

Across the moon at Grantchester!

To smell the thrilling-sweet and rotten

Unforgettable, unforgotten

River-smell, and hear the breeze

Sobbing in the little trees.

Say, do the elm-clumps greatly stand

Still guardians of that holy land?

The chestnuts shade, in reverend dream,

The yet unacademic stream?

Is dawn a secret shy and cold

Anadyomene, silver-gold?

And sunset still a golden sea

From Haslingfield to Madingley?

And after, ere the night is born,

Do hares come out about the corn?

Oh, is the water sweet and cool,

Gentle and brown, above the pool?

And laughs the immortal river still

Under the mill, under the mill?

Say, is there Beauty yet to find?

And Certainty? and Quiet kind?

Deep meadows yet, for to forget

The lies, and truths, and pain? … oh! yet

Stands the Church clock at ten to three?

And is there honey still for tea?

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!