The days of wine and roses

Richard Law, UTC 2017-08-04 18:59

The English writer Ernest Dowson (1867-1900) was born on 2 August 1867, 150 years ago. He left 75 – mercifully brief – poems, three of which are immortal (as W.B. Yeats put it), the rest of them not really worth reading – unless, that is, you like to plug through 72 poems of unremitting sadness, loss and regret, many with Latin titles, all displaying a stylish surface of fustian language without any intellectual depth at all. There are some allusions to something or other in them, but those allusions are just the mannerisms of a posing latinist with really nothing interesting to say.

His prose is even worse, having no redeeming features whatsoever: on your deathbed your weeping loved ones will hear you gurgle, 'Please can I have the hours back that I spent reading Ernest Dowson's works'.

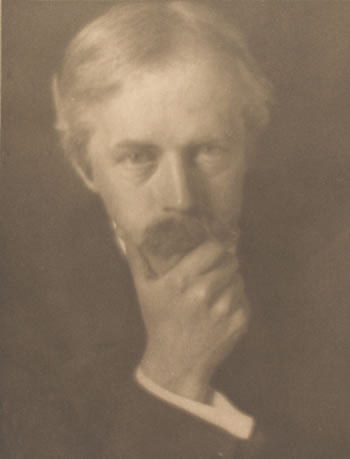

A photograph of Ernest Dowson, ND. Image: from The poems of Ernest Dowson, 1905.

Nevertheless, he hit the jackpot on the poetic fruit machine three times– and the jackpots were big, if only posthumous ones. Each of them contains at least one phrase that has passed into the folk memory of the educated English speaker.

Here they are, the jackpots. Like the rest of Dowson's poetry they require no comment or explanation (apart from the Latin titles), being entirely surface and technique:

Vitae summa brevis spem nos vetat incohare longam

They are not long, the weeping and the laughter.

Love and desire and hate:

I think they have no portion in us after

We pass the gate.

They are not long, the days of wine and roses:

Out of a misty dream

Our path emerges for a while, then closes

Within a dream.

The title is from Horace's Odes 1.4: 'The brevity of life forbids us entertaining hopes of long duration'. The title is a very characteristic Dowsonian allusion that adds nothing to the meaning, just takes eight lines to say what Horace said in one. Hit phrase: 'the days of wine and roses'.

Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae

Last night, ah, yesternight, betwixt her lips and mine

There fell thy shadow, Cynara! thy breath was shed

Upon my soul between the kisses and the wine;

And I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, I was desolate and bowed my head:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

All night upon mine heart I felt her warm heart beat,

Night-long within mine arms in love and sleep she lay;

Surely the kisses of her bought red mouth were sweet;

But I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

When I awoke and found the dawn was gray:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

I have forgot much, Cynara! gone with the wind,

Flung roses, roses riotously with the throng,

Dancing, to put thy pale, lost lilies out of mind;

But I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, all the time, because the dance was long:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

I cried for madder music and for stronger wine,

But when the feast is finished and the lamps expire,

Then falls thy shadow, Cynara! the night is thine;

And I am desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, hungry for the lips of my desire:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

Once again, the Latin title puzzles even the educated reader to a standstill before he or she even reaches the poem. The title is yet another allusion to Horace's Odes, this time 4.1: 'I am not as I was in the reign of kind and fair Cynara'. Also, as in the previous poem, the allusion adds nothing at all to the meaning, just tells us that Horace had a slightly similar thought 2,000 years previously. The phrase 'the kisses of her bought red mouth' deserves to be a hit.

Villanelle of the Poet's Road

Wine and woman and song,

Three things garnish our way:

Yet is day over long.

Lest we do our youth wrong,

Gather them while we may:

Wine and woman and song.

Three things render us strong,

Vine leaves, kisses and bay;

Yet is day over long.

Unto us they belong,

Us the bitter and gay,

Wine and woman and song.

We, as we pass along,

Are sad that they will not stay;

Yet is day over long.

Fruits and flowers among,

What is better than they:

Wine and woman and song?

Yet is day over long.

A villanelle consists of 19 lines: five stanzas of three lines followed by one stanza of four lines. It also contains repeating rhymes and two refrains. It is a form that was particularly popular among late 19th century English poets whose ideal of poetry was constructing verse according to the rules of the most complicated forms they could think up. In purely formal terms Dowson's poem is a tour de force.

The hit phrases are of course 'Wine and woman[singular] and song', by no means an original usage, as well as 'Gather them while we may' which echoes Robert Herrick's 'Gather ye rosebuds while ye may'; some will also hear that hit phrase of Browning's 'It was roses, roses, all the way, / With myrtle mixed in my path like mad'.

A portrait of Ernest Dowson by William Rothenstein (1872-1945), hand photogravure by Emery Walker (1851-1933), ND. Image: from The poems of Ernest Dowson, 1905.

On the 150th anniversary of Dowsons's birth let us leave the assessment of him to two people who knew him closely: Arthur Symons and W.B. Yeats.

Arthur Symons

Arthur Symons (1865-1945), Photographed in 1906. Image: NYPL.

Symons wrote a biographical memoir which was prefaced to the posthumous collection The Poems and Prose of Ernest Dowson (1905). Here is a slightly abridged version of the preface:

Ernest Christopher Dowson was born at The Grove, Belmont Hill, Lee, Kent, on August 2nd, 1867; he died at 26 Sandhurst Gardens, Catford, S.E., on Friday morning, February 23, 1900, and was buried in the Roman Catholic part of the Lewisham Cemetery on February 27.

[…]

Ernest had a somewhat irregular education, chiefly out of England, before he entered Queen's College, Oxford. He left in 1887 without taking a degree, and came to London, where he lived for several years, often revisiting France, which was always his favourite country. Latterly, until the last year of his life, he lived almost entirely in Paris, Brittany, and Normandy.

Never robust, and always reckless with himself, his health had been steadily getting worse for some years, and when he came back to London he looked, as indeed he was, a dying man. Morbidly shy, with a sensitive independence which shrank from any sort of obligation, he would not communicate with his relatives, who would gladly have helped him, or with any of the really large number of attached friends whom he had in London; and, as his disease weakened him more and more, he hid himself away in his miserable lodgings, refused to see a doctor, let himself half starve, and was found one day in a Bodega with only a few shillings in his pocket, and so weak as to be hardly able to walk, by a friend, himself in some difficulties, who immediately took him back to the bricklayer's cottage in a muddy outskirt of Catford, where he was himself living, and there generously looked after him for the last six weeks of his life.

He did not realise that he was going to die; and was full of projects for the future, when the £600 which was to come to him from the sale of some property should have given him a fresh chance in the world; began to read Dickens, whom he had never read before, with singular zest; and, on the last day of his life, sat up talking eagerly till five in the morning. At the very moment of his death he did not know that he was dying. He tried to cough, could not cough, and the heart quietly stopped.

[…]

Neither the stage nor the stage-door had any attraction for him; but he came to the tavern [the 'Cheshire Cheese', where the Rhymers' Club met] because it was a tavern, and because he could meet his friends there. Even before that time I have a vague impression of having met him, I forget where, certainly at night; and of having been struck, even then, by a look and manner of pathetic charm, a sort of Keats-like face, the face of a demoralised Keats, and by something curious in the contrast of a manner exquisitely refined, with an appearance generally somewhat dilapidated. That impression was only accentuated later on, when I came to know him, and the manner of his life, much more intimately.

I think I may date my first impression of what one calls "the real man" (as if it were more real than the poet of the disembodied verses!) from an evening in which he first introduced me to those charming supper-houses, open all night through, the cabmen's shelters.

I had been talking over another vagabond poet, Lord Rochester, with a charming and sympathetic descendant of that poet, and somewhat late at night we had come upon Dowson and another man wandering aimlessly and excitedly about the streets. He invited us to supper, we did not quite realise where, and the cabman came in with us, as we were welcomed, cordially and without comment, at a little place near the Langham; and, I recollect, very hospitably entertained. The cooking differs, as I found in time, in these supper-houses, but there the rasher was excellent and the cups admirably clean. Dowson was known there, and I used to think he was always at his best in a cabmen's shelter. Without a certain sordidness in his surroundings he was never quite comfortable, never quite himself; and at those places you are obliged to drink nothing stronger than coffee or tea.

[…]

Always, perhaps, a little consciously, but at least always sincerely, in search of new sensations, my friend found what was for him the supreme sensation in a very passionate and tender adoration of the most escaping of all ideals, the ideal of youth. Cherished, as I imagine, first only in the abstract, this search after the immature, the ripening graces which time can only spoil in the ripening, found itself at the journey's end, as some of his friends thought, a little prematurely. I was never of their opinion. I only saw twice, and for a few moments only, the young girl to whom most of his verses were to be written, and whose presence in his life may be held to account for much of that astonishing contrast between the broad outlines of his life and work.

The situation seemed to me of the most exquisite and appropriate impossibility. The daughter of a refugee, I believe of good family, reduced to keeping a humble restaurant in a foreign quarter of London, she listened to his verses, smiled charmingly, under her mother's eyes, on his two years' courtship, and at the end of two years married the waiter instead. Did she ever realise more than the obvious part of what was being offered to her, in this shy and eager devotion? Did it ever mean very much to her to have made and to have killed a poet? She had, at all events, the gift of evoking, and, in its way, of retaining, all that was most delicate, sensitive, shy, typically poetic, in a nature which I can only compare to a weedy garden, its grass trodden down by many feet, but with one small, carefully tended flowerbed, luminous with lilies.

[…]

But, for the good fortune of poets, things rarely do go happily with them, or to conventionally happy endings. He used to dine every night at the little restaurant, and I can always see the picture, which I have so often seen through the window in passing: the narrow room with the rough tables, for the most part empty, except in the innermost corner, where Dowson would sit with that singularly sweet and singularly pathetic smile on his lips (a smile which seemed afraid of its right to be there, as if always dreading a rebuff), playing his invariable after-dinner game of cards. Friends would come in during the hour before closing time; and the girl, her game of cards finished, would quietly disappear, leaving him with hardly more than the desire to kill another night as swiftly as possible.

Meanwhile she and the mother knew that the fragile young man who dined there so quietly every day way apt to be quite another sort of person after he had been three hours outside. It was only when his life seemed to have been irretrievably ruined that Dowson quite deliberately abandoned himself to that craving for drink, which was doubtless lying in wait for him in his blood, as consumption was also; it was only latterly, when he had no longer any interest in life, that he really wished to die. But I have never known him when he could resist either the desire or the consequences of drink.

Sober, he was the most gentle, in manner the most gentlemanly of men; unselfish to a fault, to the extent of weakness; a delightful companion, charm itself. Under the influence of drink, he became almost literally insane, certainly quite irresponsible. He fell into furious and unreasoning passions; a vocabulary unknown to him at other times sprang up like a whirlwind; he seemed always about to commit some act of absurd violence.

Along with that forgetfulness came other memories. As long as he was conscious of himself, there was but one woman for him in the world, and for her he had an infinite tenderness and an infinite respect. When that face faded from him, he saw all the other faces, and he saw no more difference than between sheep and sheep. Indeed, that curious love of the sordid, so common an affectation of the modern decadent, and with him so genuine, grew upon him, and dragged him into more and more sorry corners of a life which was never exactly 'gay' to him.

His father, when he died, [he committed suicide in August 1894, his mother killed herself barely half a year later in 1895] left him in possession of an old dock, where for a time he lived in a mouldering house, in that squalid part of the East End which he came to know so well, and to feel so strangely at home in. He drank the poisonous liquors of those pot-houses which swarm about the docks; he drifted about in whatever company came in his way; he let heedlessness develop into a curious disregard of personal tidiness. In Paris, Les Halles took the place of the docks. At Dieppe, where I saw so much, of him one summer, he discovered strange, squalid haunts about the harbour, where he made friends with amazing innkeepers, and got into rows with the fishermen who came in to drink after midnight. At Brussels, where I was with him at the time of the Kermesse, he flung himself into all that riotous Flemish life, with a zest for what was most sordidly riotous in it. It was his own way of escape from life.

[…]

He was a child, clamouring for so many things, all impossible. With a body too weak for ordinary existence, he desired all the enchantments of all the senses. With a soul too shy to tell its own secret, except in exquisite evasions, he desired the boundless confidence of love. He sang one tune, over and over, and no one listened to him. He had only to form the most simple wish, and it was denied him. He gave way to ill-luck, not knowing that he was giving way to his own weakness, and he tried to escape from the consciousness of things as they were at the best, by voluntarily choosing to accept them at their worst.

For with him it was always voluntary. He was never quite without money; he had a little money of his own, and he had for many years a weekly allowance from a publisher, in return for translations from the French, or, if he chose to do it, original work. He was unhappy, and he dared not think.

[…]

We get out of life, all of us, what we bring to it; that, and that only, is what it can teach us. There are men whom Dowson's experiences would have made great men, or great writers; for him they did very little. Love and regret, with here and there the suggestion of an uncomforting pleasure snatched by the way, are all that he has to sing of; and he could have sung of them at much less "expense of spirit," and, one fancies, without the "waste of shame" at all. Think what Villon got directly out of his own life, what Verlaine, what Musset, what Byron, got directly out of their own lives! It requires a strong man to "sin strongly" and profit by it. To Dowson the tragedy of his own life could only have resulted in an elegy. "I have flung roses, roses, riotously with the throng," he confesses in his most beautiful poem; but it was as one who flings roses in a dream, as he passes with shut eyes through an unsubstantial throng. The depths into which he plunged were always waters of oblivion, and he returned forgetting them.

[…]

It was, indeed, almost a literal unconsciousness, as of one who leads two lives, severed from one another as completely as sleep is from waking. Thus we get in his work very little of the personal appeal of those to whom riotous living, misery, a cross destiny, have been of so real a value. And it is important to draw this distinction, if only for the benefit of those young men who are convinced that the first step towards genius is disorder. Dowson is precisely one of the people who are pointed out as confirming this theory. And yet Dowson was precisely one of those who owed least to circumstances; and, in succumbing to them, he did no more than succumb to the destructive forces which, shut up within him, pulled down the house of life upon his own head.

A soul "unspotted from the world," in a body which one sees visibly soiling under one's eyes; that improbability is what all who knew him saw in Dowson, as his youthful physical grace gave way year by year, and the personal charm underlying it remained unchanged. There never was a simpler or more attaching charm, because there never was a sweeter or more honest nature. It was not because he ever said anything particularly clever or particularly interesting, it was not because he gave you ideas, or impressed you by any strength or originality, that you liked to be with him; but because of a certain engaging quality, which seemed unconscious of itself, which was never anxious to be or to do anything, which simply existed, as perfume exists in a flower. Drink was like a heavy curtain, blotting out everything of a sudden; when the curtain lifted, nothing had changed. Living always that double life, he had his true and his false aspect, and the true life was the expression of that fresh, delicate, and uncontaminated nature which some of us knew in him, and which remains for us, untouched by the other, in every line that he wrote.

[…]

He was quite Latin in his feeling for youth, and death, and "the old age of roses," and the pathos of our little hour in which to live and love; Latin in his elegance, reticence, and simple grace in the treatment of these motives; Latin, finally, in his sense of their sufficiency for the whole of one's mental attitude. He used the commonplaces of poetry frankly, making them his own by his belief in them: the Horatian Cynara or Neobule was still the natural symbol for him when he wished to be most personal. I remember his saying to me that his ideal of a line of verse was the line of Poe:

The viol, the violet, and the vine

and the gracious, not remote or unreal beauty, which clings about such words and such images as these, was always to him the true poetical beauty. There never was a poet to whom verse came more naturally, for the song's sake; his theories were all æsthetic, almost technical ones, such as a theory, indicated by his preference for the line of Poe, that the letter 'v' was the most beautiful of the letters, and could never be brought into verse too often. For any more abstract theories he had neither tolerance nor need. Poetry as a philosophy did not exist for him; it existed solely as the loveliest of the arts.

[…]

In the lyric in which he has epitomised himself and his whole life, a lyric which is certainly one of the greatest lyrical poems of our time, 'Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae,' he has for once said everything, and he has said it to an intoxicating and perhaps immortal music.

Here, perpetuated by some unique energy of a temperament rarely so much the master of itself, is the song of passion and the passions, at their eternal war in the soul which they quicken or deaden, and in the body which they break down between them. In the second book, the book of "Decorations," there are a few pieces which repeat, only more faintly, this very personal note. Dowson could never have developed; he had already said, in his first book of verse, all that he had to say. Had he lived, had he gone on writing, he could only have echoed himself; and probably it would have been the less essential part of himself; his obligation to Swinburne, always evident, increasing as his own inspiration failed him. He was always without ambition, writing to please his own fastidious taste, with a kind of proud humility in his attitude towards the public, not expecting or requiring recognition. He died obscure, having ceased to care even for the delightful labour of writing. He died young, worn out by what was never really life to him, leaving a little verse which has the pathos of things too young and too frail ever to grow old.

W.B. Yeats

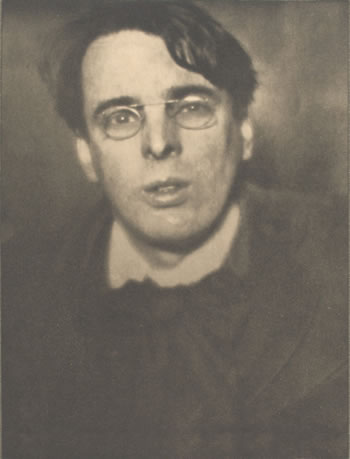

William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), photographed in 1908. Image: NYPL.

W.B. Yeats' account of Dowson is in his book of reminiscences of that period, The Trembling of the Veil, 1922. Here are some passages concerning Dowson:

Chapter V

[Walter] Pater had made us learned; and, whatever we might be elsewhere, ceremonious and polite, and distant in our relations to one another, and I think none knew as yet that Dowson, who seemed to drink so little and had so much dignity and reserve, was breaking his heart for the daughter of the keeper of an Italian eating house, in dissipation and drink; and that he might that very night sleep upon a sixpenny bed in a doss house. It seems to me that even yet, and I am speaking of 1894 and 1895, we knew nothing of one another, but the poems that we read and criticised; perhaps I have forgotten or was too much in Ireland for knowledge, but of this I am certain, we shared nothing but the artistic life.

Chapter VII

[Yeats compares Dowson with another writer of the era, Lionel Johnson]

Not till some time in 1895 did I think he [Lionel Johnson] could ever drink too much for his sobriety – though what he drank would certainly be too much for that of most of the men whom I knew – I no more doubted his self-control, though we were very intimate friends, than I doubted his memories of Cardinal Newman. The discovery that he did was a great shock to me, and, I think, altered my general view of the world.

He seemed perfectly logical, but a little more confident and impassioned than usual, and I had, I think, promised to accept – when he rose from his chair, took a step towards me in his eagerness, and fell on to the floor; and I saw that he was drunk. From that on, he began to lose control of his life; he shifted from Charlotte Street, where, I think, there was fear that he would overset lamp or candle and burn the house, to Gray’s Inn, and from Gray’s Inn to old rambling rooms in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and at last one called to find his outer door shut, the milk on the doorstep sour. Sometimes I would urge him to put himself, as Jack Nettleship had done, into an Institute. One day when I had been very urgent, he spoke of 'a craving that made every atom of his body cry out' and said the moment after, 'I do not want to be cured,' and a moment after that, 'In ten years I shall be penniless and shabby, and borrow half-crowns from friends.'

Chapter VIII

I began now to hear stories of Dowson, whom I knew only at the Rhymers, or through some chance meeting at Johnson’s. I was indolent and procrastinating, and when I thought of asking him to dine, or taking some other step towards better knowledge, he seemed to be in Paris, or at Dieppe. He was drinking, but, unlike Johnson, who, at the autopsy after his death, was discovered never to have grown, except in the brain, after his fifteenth year, he was full of sexual desire. Johnson and he were close friends, and Johnson lectured him out of the Fathers upon chastity, and boasted of the great good done him thereby. But the rest of us counted the glasses emptied in their talk. I began to hear now in some detail of the restaurant-keeper’s daughter, and of her marriage to the waiter, and of that weekly game of cards with her that filled so great a share of Dowson’s emotional life. Sober, he would look at no other woman, it was said, but, drunk, would desire whatever woman chance brought, clean or dirty.

[…]

Johnson’s poetry, like Johnson himself before his last decay, conveys an emotion of joy, of intellectual clearness, of hard energy; he gave us of his triumph; while Dowson’s poetry is sad, as he himself seemed, and pictures his life of temptation and defeat,

Unto us they belong,

Us the bitter and gay,

Wine and woman and song.

Their way of looking at their intoxication showed their characters. Johnson, who could not have written Dark Angel if he did not suffer from remorse, showed to his friends an impenitent face, and defeated me when I tried to prevent the foundation of an Irish convivial club – it was brought to an end after one meeting by the indignation of the members’ wives – whereas the last time I saw Dowson he was pouring out a glass of whiskey for himself in an empty corner of my room and murmuring over and over in what seemed automatic apology 'The first to-day.'

Chapter IX

I think Dowson’s best verse immortal, bound, that is, to outlive famous novels and plays and learned histories and other discursive things, but he was too vague and gentle for my affections.

Chapter XIV

Dowson was now at Dieppe, now at a Normandy village. Wilde, too, was at Dieppe; and Symons, Beardsley, and others would cross and recross, returning with many tales, and there were letters and telegrams. Dowson wrote a protest against some friend’s too vivid essay upon the disorder of his life, and explained that in reality he was living a life of industry in a little country village; but before the letter arrived that friend received a wire, 'arrested, sell watch and send proceeds.' Dowson’s watch had been left in London – and then another wire, 'Am free.' Dowson, ran the tale as I heard it ten years after, had got drunk and fought the baker, and a deputation of villagers had gone to the magistrate and pointed out that Monsieur Dowson was one of the most illustrious of English poets. 'Quite right to remind me,' said the magistrate, 'I will imprison the baker.'

A Rhymer had seen Dowson at some cafe in Dieppe with a particularly common harlot, and as he passed, Dowson, who was half drunk, caught him by the sleeve and whispered, 'She writes poetry – it is like Browning and Mrs Browning.'

Then there came a wonderful tale, repeated by Dowson himself, whether by word of mouth or by letter I do not remember. Wilde has arrived in Dieppe, and Dowson presses upon him the necessity of acquiring 'a more wholesome taste.' They empty their pockets on to the café table, and though there is not much, there is enough if both heaps are put into one. Meanwhile the news has spread, and they set out accompanied by a cheering crowd. Arrived at their destination, Dowson and the crowd remain outside, and presently Wilde returns. He says in a low voice to Dowson, 'The first these ten years, and it will be the last. It was like cold mutton' – always, as Henley had said, 'a scholar and a gentleman,' he no doubt remembered the sense in which the Elizabethan dramatists used the words 'Cold mutton' – and then aloud so that the crowd may hear him, 'But tell it in England, for it will entirely restore my character.'

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!