Moral money

Richard Law, UTC 2017-08-10 09:09 Updated on UTC 2017-11-06

We shall not see their like again: the Swiss series 5 banknotes, first issued 60 years ago in 1957, designed by the Swiss artist, Pierre Gauchat (1902-1956).

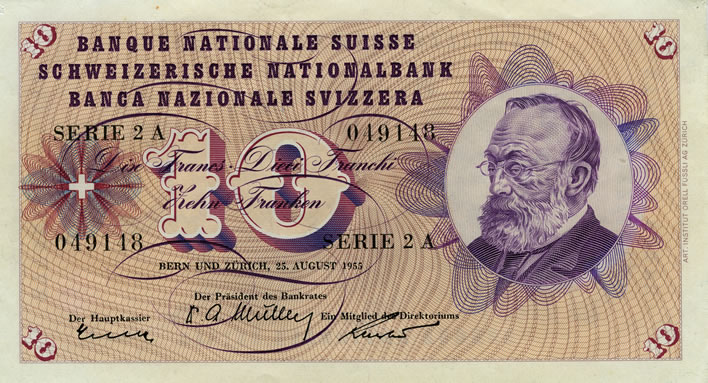

For completeness, we should mention that in series 5 the two smallest denominations, 10 and 20 francs, were traditional designs bearing the images of two Swiss notables: Gottfried Keller (1819-1890), the writer, on the 10-franc note und General Guillaume Henri Dufour (1787-1875), a polymath and the first general of the young Swiss Confederation, on the 20-franc note. Both those notes were a workmanlike effort by Hermann Eidenbenz in 1956 and stylistically completely different from Gauchat's work, so we can leave them aside with a clear conscience.

Great names and alpine flowers for the metaphorically challenged: The writer Gottfried Keller and the Nelkenwurz (geum); General Dufour and the Silberdistel (carline thistle).

In contrast, Gauchat's four designs for the higher denomination notes were quite astonishingly bold. For 23 years, until the series was withdrawn in 1980, Swiss wallets and purses were padded and decorated by these subtle works.

Gauchat's designs had another property, which one noticed only in time: they aged gracefully, their images acquiring the modest glamour of a distressed fresco.

Let's look at them one by one.

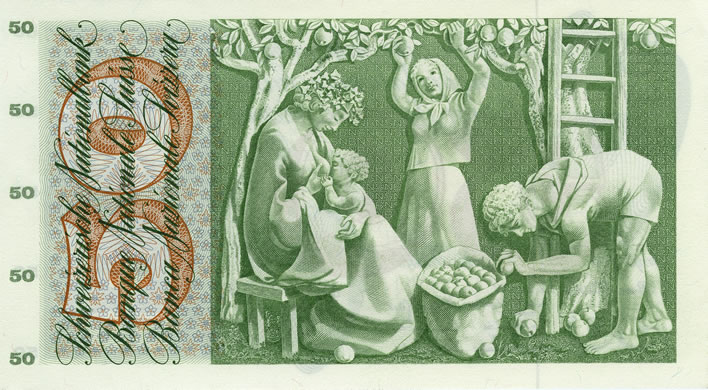

Fifty francs: The Apple Harvest

The 50-franc note sticks in my memory the most, probably because this poor student at the University of Zurich barely glimpsed the higher denominations, which would arrive in his hand and leave promptly with a cheerful wave, never risking outstaying their welcome.

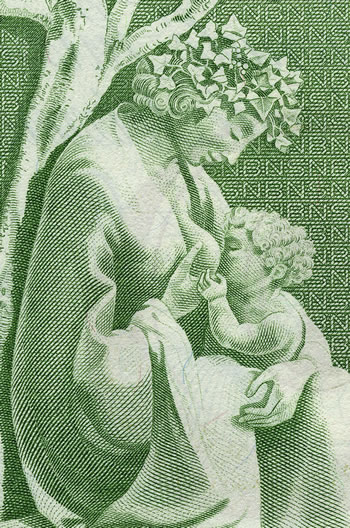

The front of the note displays a girl's head. Her image is not idealized: her smile is slightly crooked; a wisp of hair droops over her left eye, a clever touch that gives an air of spontaneity. She is looking directly at us, open-eyed. Her clothes are everyday, unremarkable. Sunlight dapples her smiling face. She is wearing a coronal of apple leaves and blossom; one of the blossoms has fallen onto her pullover. [Remember: nothing in the work of a great artist is ever accidental.]

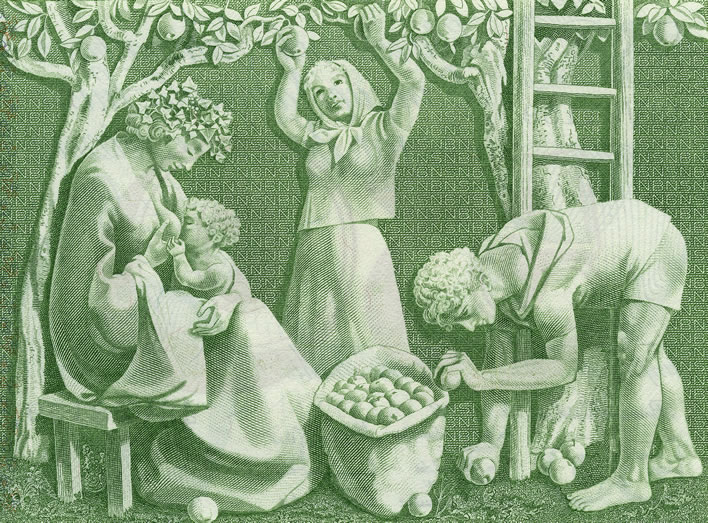

The rear of the note bears a scene of an apple harvest. The colour of both the front and the back of the note is a deep apple-green.

On the left of the tableau a smiling mother is sitting on a rustic bench looking adoringly at her breastfeeding infant. She is wearing on her head a coronal not of apple-leaves and blossom, but of ivy, alluding to the coronals of ivy worn by the Greek god Dionysus and his followers: a symbol of fertility, generation and agriculture, which, when you think about it, are really all just aspects of the same thing. Gauchat the artist would certainly have been familiar with this symbolism.

In the centre a young woman is picking the fruit from the apple trees. On the right, a young man is bending over collecting apples from the ground and putting them into a brimming sack.

The metaphorically-minded will stare at this image for a long time. They will note how the young girl with the apple-blossom coronal on the front of the note has become the mother feeding her child: the blossom has changed its nature.

They will note the harvesting of the fruits of Nature and the imagery of human effort; husbandry, the fecundity of Nature and the fecundity of humans that is the basis of sane economics and sane money. The images swirl in closed circles: the blossom, the fruit, the harvest; the mother, the infant, the young woman and the man; sitting, standing, bending; the small tree, the great tree, the ladder and the sack of apples; human effort and prudence – childrearing, picking and storing the result of that labour.

When you – student pauper! – on Friday have paid for your first proper lunch of the week, waving a moist-eyed farewell to the 100-note, acquired just that morning, and now have a Gauchat fifty, a Dufour and a few pleasingly solid silvery coins on the table, it is upon the Gauchat that you will gaze and ponder, whilst drinking your coffee, upon the role that your tiny transaction has played in the grand economic scheme of things.

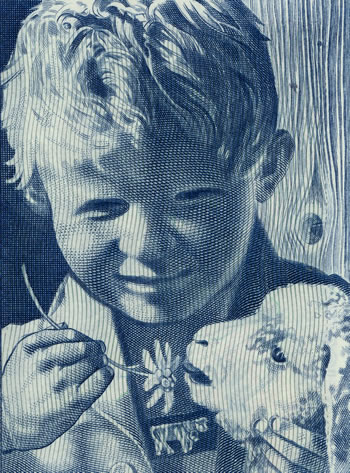

One hundred francs: Saint Martin

On the front of Gauchat's 100-note is the face of a smiling young boy holding a lamb and a flower. As with the girl on the 50-note it is a very figurative image, also dappled in sunlight.

The boy has wavy, rough-cut blonde hair. Under his jacket there is a breastband with an image of a cow and cowbell, suggesting that this might be a folk costume he is wearing and that he is the son of a farmer. The background appears to be the rough wood of the wall of a barn. The boy is holding a lamb and an edelweiss flower (at one time safe on alpine meadows, now two-a-penny in every garden centre). The flower of the Swiss nation and the lamb of peace.

The rear of the note has a surprise in store for us: a portrait of the warrior saint, Saint Martin of Tours (316?-397), in a famous moment from his greatest legend.

Martin was among the cavalry of the Imperial Guard of the Emperor Constantine II in Amiens. Over his armour he wore the uniform cloak of the Guards, lined with lambswool. The legend says that at the city gate of Amiens in winter he encountered a naked beggar, shivering in the cold. Having nothing with him but his weapons and his cloak, he took his sword and cut his cloak in half, giving one half to the beggar.

The story of Saint Martin's direct, practical Christian charity to the poor has become a core idea of all Christian faiths – Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican and Orthodox. Martin's deed is represented in many images in many churches around the world, the symbol of the sword wielded to charitable purpose is comprehensible to anyone.

Gauchat has set the scene in dark blue, representing the winter night. What can this all mean? On a banknote?

Martin's Christian faith was strengthened to the point where he renounced his military career, changing from being miles Caesaris, the Emperor's soldier, to being miles Christi, Christ's soldier. The Swiss are no pacifists: their militia military is the backbone of their doctrine of armed neutrality. At the bottom left of the image we see the warrior saint's helmet and satchel, put down, but not abandoned.

The presence of General Dufour on the 20-franc note may help us to understand at least something of what Gauchat is saying to us. Dufour was not only a general (four times over, in fact), but an engineer and cartographer and, above all, a co-founder with Henry Dunant of the International Red Cross. He was its first president. The Red Cross is still based in Geneva, Dufour's adopted city. The edelweiss flower held by the boy in the portrait on the front of the note is the rank insignia of a Swiss general and has been on the value side of that wonderfully massive coin, the five-franc piece, for nearly a century.

The metaphorically-minded see the image of the young boy on the front of the note, his pleasure in tradition, in patriotism and the lamb of peace, then see the warrior saint portrayed in a famous act of charity towards the poor – in short the adult Swiss male, serving in a militia army dedicated to patriotism and peace, armed neutrality combined with Christian charity. The saint and the boy have the same wavy, rough-cut blonde hair – their physical and allegorical identity is clear to see.

The saint's charity is a rational, practical charity: his cloak was halved so that out of excess both parties had sufficiency. It was not the charity of the zealot, the ascetic and martyr, who would have given the entire cloak to the beggar and rejoiced in his own suffering. Cutting the cloak in half so that both parties benefit expresses the Swiss psyche perfectly, a nation famous for the 'Swiss compromise'.

Having considered the 50 and 100-franc notes, modern snowflakes will be fanning themselves at the outrageous gender stereotyping there was in 1956: girls have babies, attend housekeeping courses and boys do military service. But that discussion is for another post.

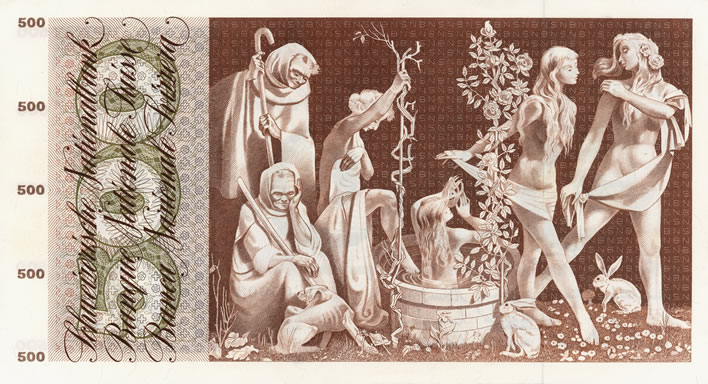

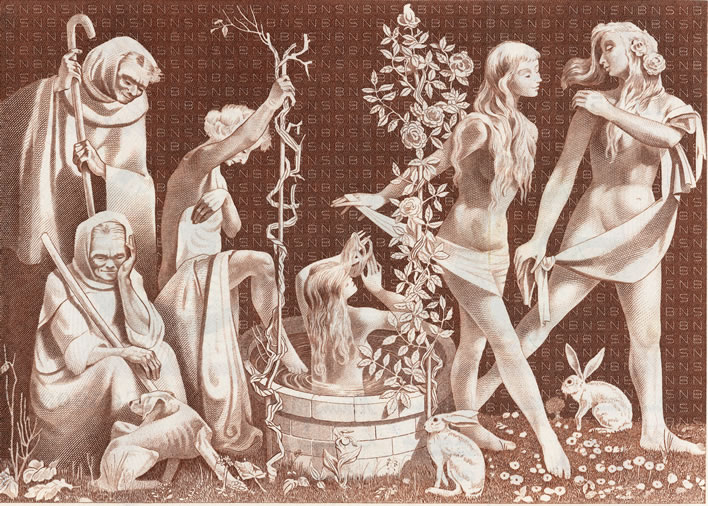

Five hundred francs: The fount of youth

The front and rear of the 500-franc note is brown. The colour of autumn, the colour of ageing.

The portrait on the front of the 500-franc note is that of a middle-aged woman wearing a headscarf, staring intently into a handheld mirror. Gauchat's design emphasises the intensity of the stare, although the rest of the face remains relatively emotionless.

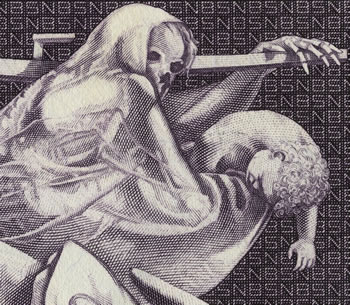

The image on the rear is a tableau representing the fountain of youth.

The narrative of the image moves naturally from left to right. On the extreme left there is an elderly woman standing, supported by a crook. At her feet another old woman is sitting holding a staff, her head resting on her hand. Both of the women are looking down at an emaciated dog – the latter a traditional symbol of melancholy. The heads of the old women are covered in scarves. The vegetation on the left of the pool is parched and leafless. All is age and depression.

A younger woman is stepping into the pool, steadying herself by holding on to an almost leafless stem alongside. In the centre of the image, one girl is already in the pool – the transition point between decay on the left and rejuvenation on the right.

On the right we see the rejuvenated: the stem on this side is in full leaf and flower – it is a rose bush. Two young women have just emerged from the fountain and are striking what can only be described as self-confident, self-regarding, balletic or even model poses. The grass on which they are standing is sprinkled with small flowers – a renaissance meadow. There are two hares, traditional symbols of fertility, rebirth and resurrection (one hare is not enough, children, ask your parents).

Although Gauchat's symbolism is superficially clear, the deeper message is not. The dream of rejuvenation is misguided – at least it was in 1957 – but is this image only moralizing on a banknote? Is Gauchat preparing the ground for what is to come in his next design?

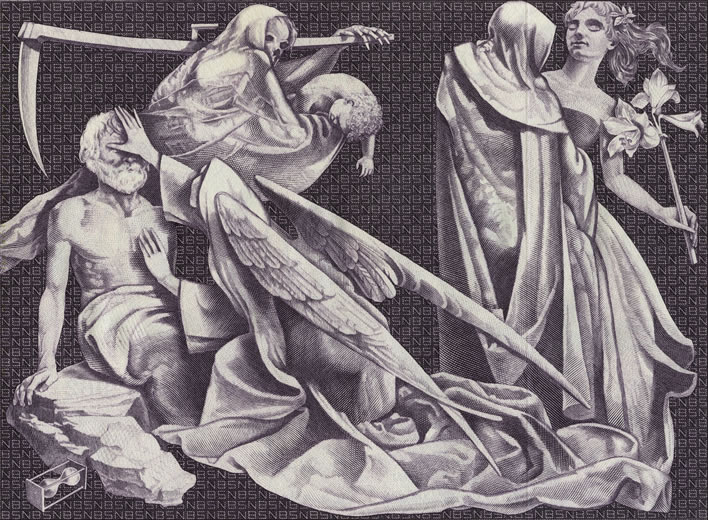

One thousand francs: The Dance of Death

Well, after delighting us with rustic apple harvesting, astonishing us with the warrior saint's charity and puzzling us with the fountain of youth, what can Gauchat do next? The Dance of Death, that's what.

The Dance of Death has been a staple subject of the artist's trade for the last thousand years, but, at least to my knowledge, never on a banknote. And not just any banknote: at that time the 1,000-franc note was the most valuable banknote in the world. Even I can remember a time when cash was still king and not just something drug dealers used, a time when Swiss friends would buy new cars with wads of these. Perhaps Gauchat is just saying to the plutocrats, 'you can't take it with you'.

The face on the front of the note is haunting: it is the face of a woman transfixed, staring appalled into the cowl of the creature in front of her. The expression is of pure hypnotic horror. In her hair is a small cluster of what appear to be laurel leaves.

The colour of the note is a deep purple, almost approaching black. The rear of the note expands the theme without pity.

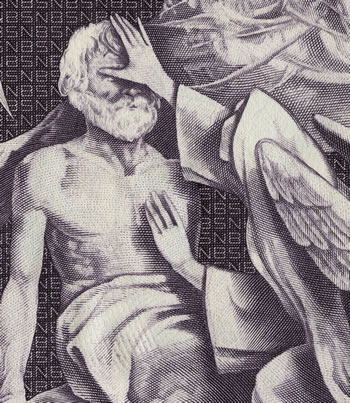

At the bottom left we see one of the standard symbols of the Dance of Death tradition, the hour-glass, here knocked over. There are three major elements in the composition. Let's look at them in detail.

On the left an old man is being taken by a winged angel of death, one hand in front of his head, one hand in front of his heart. The hand over his face seems to be engaged in that post-mortem duty, the closing of the eyelids.

At the rear of the group we see the Grim Reaper, who seems to be flying past. He is carrying a scythe over his left shoulder and a dead child in his right arm. There is no tenderness or ceremony on display here – the child could just as well be a sack of flour. In the entire image, only the Grim Reaper's skull face is shown in some detail.

On the right is the woman from the image on the front of the note. We presume it is her, because she, too, has a cluster of leaves in her hair. She is held by the cowled figure and is swaying with the dance, her eyes closed, her hair loosened and flowing with movement, her necklace gone – no, you really can't take it with you.

In her hand there is a large stem of Madonna lilies, the traditional symbol of innocence and virginity that is found in paintings of the Annunciation, here part of a grimmer message. The plant is oversized: we cannot overlook it. The face of the cowled figure is unseen.

Death takes the old, the young and the middle-aged without distinction. It may be announced, just as a birth may be announced, but at some moment there is no more sand to run through the neck of the glass and the sand-glass is kicked over.

It could have been much worse for us: Gauchat has spared us the gaping skeletons of the traditional Dance of Death. Apart from a glimpse of the Grim Reaper's skull, the skeletal aspects of the ministrants of death are not explicit – and that is wise and clever. Dancing skeletons would have been a step too far. The horror in the eyes of the woman on the front of the banknote is sufficiently clear, without showing the terrible face of her partner in this dance. In fact, Gauchat's reticence enhances the horror for the viewer.

Gauchat placed this image on the banknote of the well-heeled. I – pauper! – never saw one of these notes close up. In some ways I'm quite glad I didn't – the fecundity of the apple harvest and the compassion of Saint Martin were quite enough for me.

The cultural fracturing of modern society and the degradation of the historical sensibility mean that we really will never see the like of Gauchat's work on modern banknotes again. The reader is invited to consider the uproar that would break out nowadays over any one of his designs.

These days the Euro banknotes show us pictures of non-existent bridges and buildings; the Swiss banknotes of the newest series display really controversial subjects such as 'wind' and 'light'. The previous two published Swiss series were design masterpieces, but cool and intellectual, based around the images of Swiss artists. architects and scientists – the emotional and metaphorical charge we find in Gauchat's work quite missing.

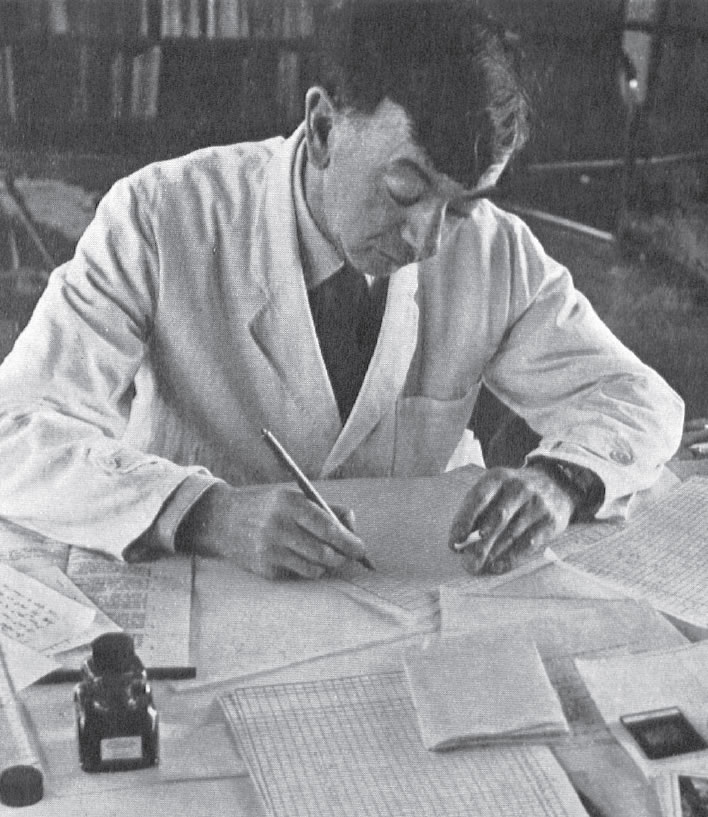

Pierre Gauchat

Pierre Gauchat in his studio, unknown date and source. He died only 54 years old in 1956 in Cairo, where he had gone to overwinter for his health. He died of a stroke silently in his sleep – the angel of death came unannounced and placed a hand over his head. He did not live to see the appearance of his banknote designs.

Update 11.08.2017

The author would like to thank the Swiss National Bank for its help in providing high-resolution images of the Series 5 banknotes. As a result of this help the article has been thoroughly revised to incorporate the new material.

The image source unless otherwise stated is Archives of the Swiss National Bank.

These images must not be copied or reused without the explicit written permission of the Swiss National Bank.

Update 06.11.2017

St Martin's Day in the German Rhineland

A movement has been started to have the St Martin's Day processions in Catholic Germany recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage. Some extracts from the report in the NZZ [DE only].

Many Germans and their children make lanterns for the processions held on Martin's Day, 11 November. On this day, St Martin, wrapped in a red cloak, rides through the town or village at the head of a procession of children carrying lanterns, accompanied by a marching band.

The highpoint of the festivity is the cloak scene, when Saint Martin slices his cloak in two with his sword. One half he gives to the begger in the road, which signals that the moment has arrived when the children are given a 'Martin-Pretzel' or a bag with sweets and fruit.

Two people from the region, a Catholic stronghold in Germany, are trying to get the Martin Societies in the Rhineland recognised as an 'Intangible Cultural Heritage' (ICH) by Unesco.

One of them, René Bongartz, had played the 'beggar' for 27 years in his village. 'The idea of sharing is not a specifically Christian idea, but in the true meaning of the word a humane idea', which thus appeals to representatives of all faiths.

And so really is the sort of thing one should have on banknotes.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!