The Gotthard Pass: the heart of Switzerland

Richard Law, UTC 2017-08-01 07:00

Excuses

- Our sloppy application of modern country names such as Switzerland, Germany and Italy to times before these nations even existed will annoy professional historians, but these tokens are used here as shorthand geographic locators for the convenience of modern readers and not as definitions of nationality.

- We have generally used the German names for places.

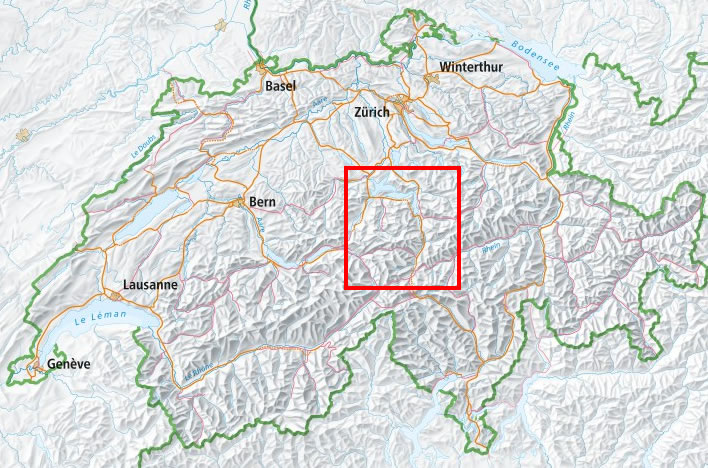

Location guide

The Gotthard Pass region in Switzerland: between Luzern, the Vierwaldstättersee (Lake Lucerne), Flüelen, Altdorf, Erstfeld, Silenen, Amsteg, Wassen, Göschenen, the Schöllenen gorge, Andermatt in the Urserental (where the Furka Pass from the west and the Oberalp Pass from the east meet), the summit of the Gotthard Pass, Airolo in the Tessin and Italy beyond it. Images: ©Data: swisstopo, FEDRO, FEDRO + canton. Online.

[Click on the image to open a large version (1368 x 1368 px) in a new tab]

The cradle of the Urserental

There is a blessèd plot in the Swiss Alps called the Urserental, the Urseren valley, around 1,500 metres (5,000 feet) above sea level. On good summer days it is heaven on earth – unless, of course, you prefer lounging around half-naked on some tropical beach, in which case there is no hope for you; on bad summer days there are thunderstorms with hail and horizontal lightning, and rocks tumbling down on the just and the unjust; on bad winter days it is a freezing hell on earth, with snow, ice, winds that roar down from even colder places and avalanches also tumbling down on the just and the unjust; on good winter days there is brilliant sun and in modern times skiing for the rich. Apart from those who prefer to bronze themselves on beaches, why would anyone not want to live here? As an added bonus, a lifetime here will give you the creased leather face that only long exposure to real weather creates.

The Urserental: a nice place to be when the sun shines. Image: ©Carlo Pisani, swissinfo.ch.

Europe warmed up in the Middle Ages, in the climate period between about 900 and 1300 that is now known as the Medieval Warm Period (MWP). In those clement times the high valley of the Urserental attracted the surplus population of the canton Wallis (Valais) in the western Alps. The people in Wallis were originally Alemannen from south Germany but had developed their own mountain-dweller identity: the Walser.

In Wallis there are some wonderful high meadows, too, like Urserental, but its main features are its deep gorges and the inaccessibility of its mountain villages. The Walser scratched a living from this place, becoming experts at building paths and water channels (called Suonen) around formidable vertical cliffs. A large part of the early history of the high places of Switzerland is the regulation of water rights: in a landscape of rock and high meadows, water is the key to everything. It is, as is often said, Switzerland's only natural resource.

The Walser migration to the Urserental was a fact of geography as well as climate. From ancient times a good route existed between Brigg in Wallis and Andermatt in the Urserental: the Furka Pass. Taking this route, the surplus Walser resettled in the Urserental in the 1100s. Some didn't stop there but went further eastwards, from Andermatt across the Oberalp pass and down to Disentis in the valley of the Upper Rhine in what is now Graubünden (Grisons). Settling in the side valleys of Graubünden they built their characteristic villages, strings of dwellings like beads on a necklace, layouts that can still be seen today.

The movement in the east was not one way: the Germanic and Rhetoromanic peoples of Graubünden also found their way up to the Urserental and made their homes there.

The Urserental from Realp/Hospental to Andermatt, 2008. The Furka Pass from Wallis enters at the end of the valley at the bottom of the picture; the Oberalp Pass to Disentis, Graubünden, is the route running between the mountain ranges at the back of the picture; the Schöllenen/Gotthard is the gorge at the end of the valley (Andermatt) near the top left. Image: ©Schweizer Luftwaffe 2008.

Readers who are still fighting to keep awake will have already inferred the importance of the position of the Urserental at the centre of this east-west axis: the Furka Pass to the west and the Oberalp Pass to the east. There was also a relatively unproblematic passage to the south over the pass and down the Biascatal, following the river Ticino to Bellinzona, then moving easily to Lugano and Milan, then further with even easier access to the fertile plain of the Po and its great city states: Verona, Padua and Venice; Mantua, Modena, Bologna. Then the great road south to Rome with Florence and Siena on the way. Lombardy would become one of the great cultural and trading centres of the Middle Ages.

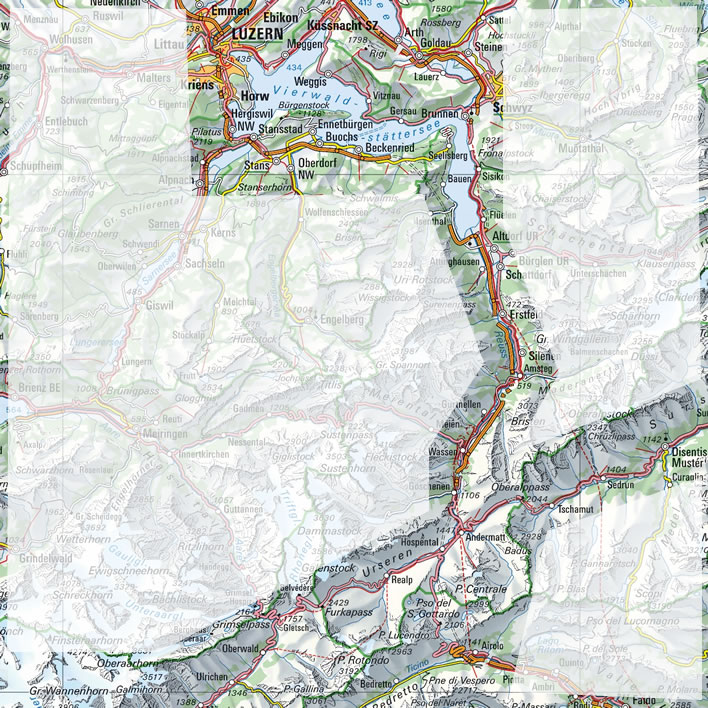

The Gotthard Pass in detail, from Flüelen to Airolo. In the bottom third of the map note the crossroads function of the Urserental, a meeting place for all the points of the compass. Images: ©Data: swisstopo, FEDRO, FEDRO + canton. Online.

[Click on the image to open a large version (1172 x 2213 px) in a new tab]

The Urserental was a T-junction that was about to become a crossroads.

Opening up the Schöllenen

But what about to the north, to lowland Switzerland and thence to the peoples of northern Europe, the Germans, French and Dutch?

The part of the Urserental next to Andermatt where the Gotthard route plunges down into the Schöllenen, 2010. The two existing Teufelsbrücken can be seen in the centre. The 1882 railway line takes its own route here to the left and into the cliff. The south entrance to the Urnerloch is hidden under the modern avalanche gallery. Image: ©Schweizer Luftwaffe.

The inhabitants of the Urserental had some communication with the villages in the Reuss valley to the north of them, but these passages were difficult: high, exposed tracks, barely passable in winter, mostly over the Bäzberg mountain. The transport of goods was tedious and expensive and the beasts of burden were probably human, not animal, with large packs strapped on their backs.

None of these tracks really deserved the name 'pass' – they required first a climb and then a descent of an extra 1,000 metres (3,000 feet) that would add at least a day to the transit time. Their altitude and the infrequency of their use made following them particularly problematic in winter and bad weather conditions; they took travellers far away from settlements and refuge. Transit times over such routes could not simply be totted up in consecutive hours – no one wanted to be on the move in the winter night, animals and travellers had to rest and eat, meaning that the journey had to be broken up into stages taking no more than six or seven hours.

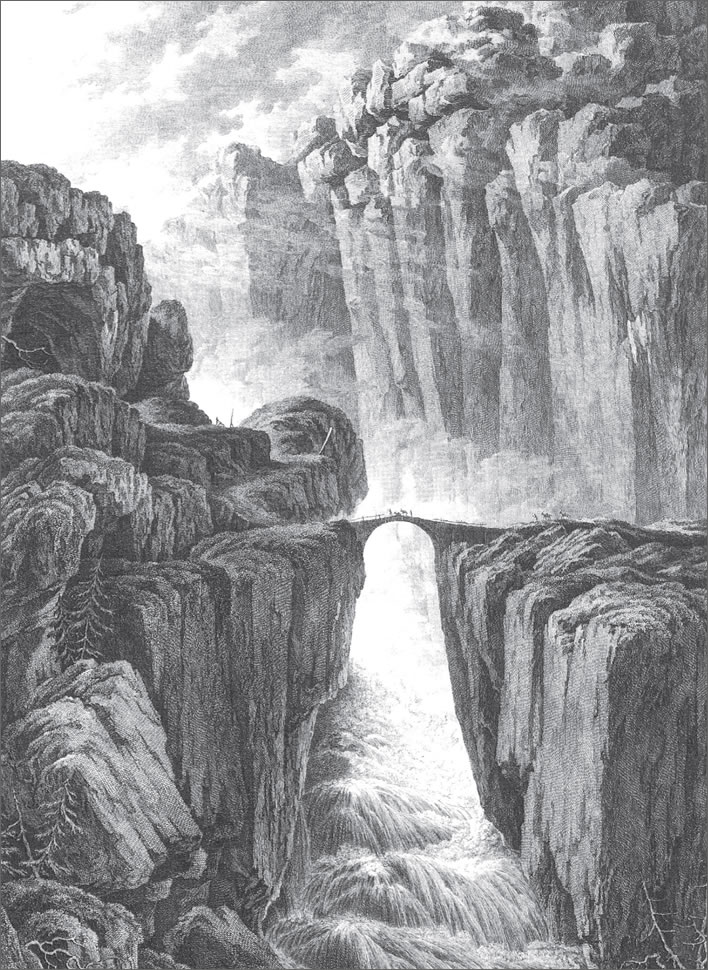

Joseph Mallord William Turner, (1775-1851), The Schöllenen Gorge from the Devil’s Bridge, Pass of St Gotthard, 1802. Turner captures well the frightfulness of the route for the contemporary traveller. Image: ©Tate Gallery, London.

To the north below the Urserental lay the rich and populous lands of Switzerland, but the only direct connection was the Schöllenen gorge, a narrow slit between precipitous rockfaces, its bottom filled with the thundering River Reuss, that crashed down over fallen rocks in a steep bed. Topography, geography and geology funneled wind, rock and avalanches down this crack.

The Schöllenen gorge in June 2015: still dropping rocks at will on the just and the unjust. All credit to the builders of these modern galleries that can withstand such a battering. Nevertheless, some temporary support from a good old-fashioned tree-trunk may be needed (under the rock at the edge of the gallery). Image: ASTRA/Luzerner Zeitung.

Before 1200 the larger world knew nothing of the valley of the Reuss. The communities of the Urserental above the Schöllenen and the communities of Uri below it lived largely separate lives; the religious and political centre for the Ursener was the great abbey of Disentis down the Oberalp Pass in Graubünden, for the Urner it was Zürich.

The Twärrenbrücke

The Urseren, now fortified with Walser skills, knew how to deal with plunging gorges and precipitious rockfaces. At some time around 1200-1220 they worked their way down the Schöllenen gorge.

The first obstacle was the granite nose of the Kirchberg, sticking out into the right-hand side of the Reuss, impassable except by mountain goats and foolhardy humans. There they did what Walser did best, they built a wooden gallery around the nose – just another sort of Suonen, really. They drove irons into the rock to support the a wooden walkway, drove iron pegs into the rock above and hung chains from them to help support the outer edges of the walkway. Of this walkway we have neither contemporary description nor illustration, so that much of the our description is speculation. The walkway became known as the Twärrenbrücke, the 'plank bridge'. We'll refer to it in English as a walkway, to avoid the misleading term 'bridge'.

Walking along it was an adventure at the best of times, even more so when it was covered in snow or iced over from the frozen spume that rose from the tumbling Reuss. It must have been especially adventurous on the frequent occasions the Reuss was in full flood: a thunderstorm upstream in the Urserental or melting snow water in spring would turn the Reuss, already a torrent, into a foaming cascade full of flying rocks and tree trunks. Squeezed between the sheer walls of the gorge the water level would rise to unbelievable heights within minutes.

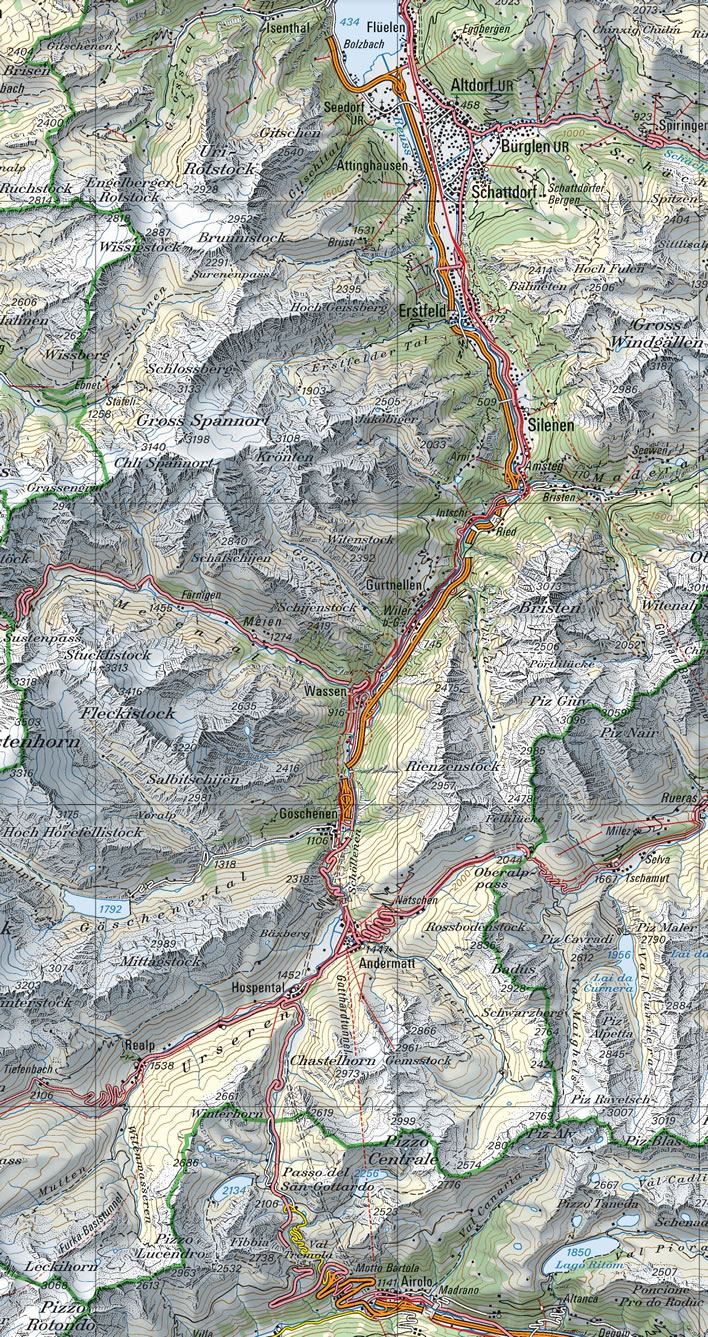

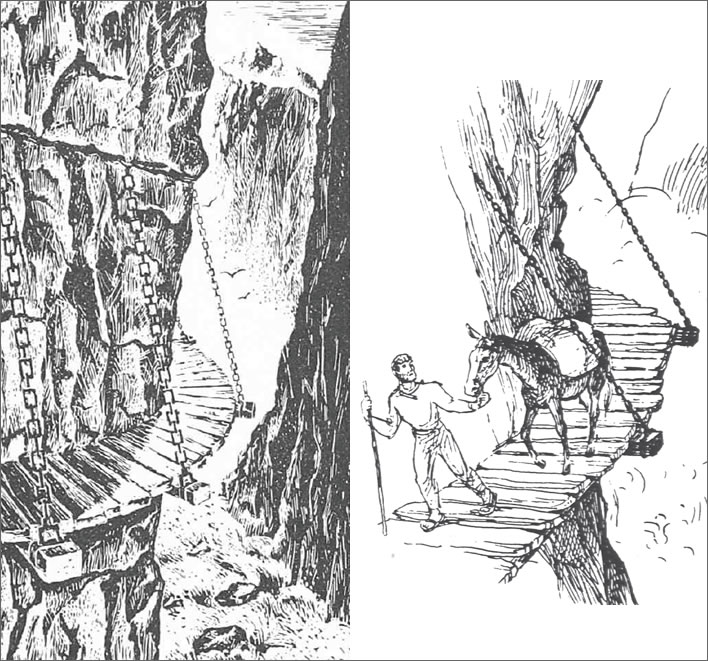

A collection of nonsensical representations of the Twärrenbrücke that have become firmly lodged in the modern imagination. The Swiss dialect word twerr can mean 'cross, crosswise', as in its modern cognate quer, which led to the idea that the walkway was given its name because of its cross planking. However, twerr can mean many other things, particularly in connection with wooden beams, where the twerrbalcheis in fact the beam that runs along the ridge of a roof. We don't need etymological arguments to reject this assumption, we just need to look at the impossible structures to which it has given birth.

This drawing is the most famous illustration of the fantasy Twärrenbrücke, done by Theodor Barth (1875-1949) to illustrate the Swiss children's book Der Schmied von Göschenen, 'The Blacksmith from Göschenen', by Robert Schedler (1866-1930), 1919. The book is a Swiss children's classic, a fantasy tale about the creation of the Gotthard. The book is entertaining and feeds the Swiss desire for the mythmaking of their past. It has, however, only the most tenuous connection with real history and simply pours inventions into tiny Swiss heads at their most impressionable, rather like the Robin Hood saga does for English speaking children.

Just a look at Barth's drawing of the Twärrenbrücke shows that in this form it would never hold up; the mysterious black line along the structure would have to be a modern steel girder in order to support the load; there seem to be two layers of cross-beams; No medieval joiner would cut at great effort the planks that surface the walkway nor the hundreds of wooden pegs that held it together; no blacksmith would forge the hundreds of nails that would be the alternative fastening technique. Those wishing to give Barth the benefit of the doubt should try and replicate this design with lolly-sticks and string. Good luck!

The image on the left is taken from a journal for civil engineering, which fact is deeply worrying, even when we disregard the rectangular chain links. Image: Stampf, Walter. 'Brücken über kriechende Gehängeschuttdecken', Schweizerische Bauzeitung, vol. 95, 1977, Heft 26, drawing by Rudolf Sager, 'Twärrenbrücke des 13. Jahrhunderts' 1972. Online.

The image on the right is the kind of thing that teachers give to their classes. Image: Wandeler, Max. 'Das luzernische Postwesen bis 1848', Schweizer Schule, vol. 39, 1952, Heft 7, p. 209-222, online.

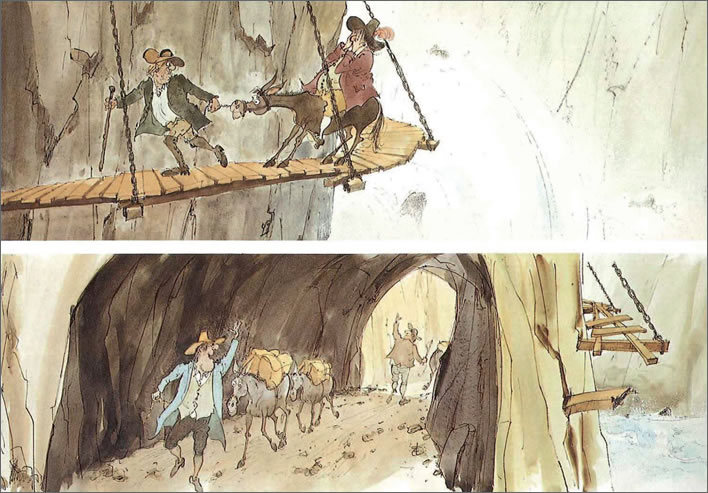

This image is a cheerful cartoon published by the Gotthard Museum, illustrating the advantages the creation of the Urnerloch brought. Once again, beautiful horizontal planks across beams. Image: 'Twärrenbrücke vor und nach der Sprengung des Urnerlochs durch Morettini 1707', Führer 'Gotthardmuseum', 1989.

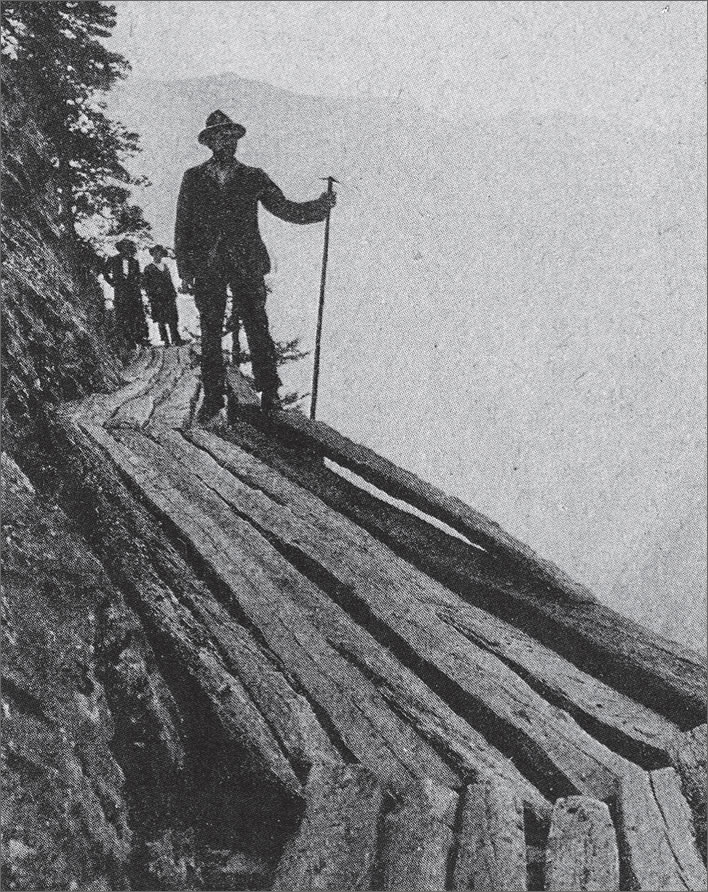

This is how you build a walkway that is economical and efficient in its use of materials. This is the 'Latma' walkway between the Tellwald and Leiggern above Raron in Wallis, around 1900. The planks are rough-cut and laid lengthways. The gentleman in the picture is clearly a Walser, preferring to stand on the outer edge of the walkway above the abyss, whereas normal people would be pressing themselves against the rock. Image: 'Hochmittelalter und frühes Spätmittelalter (950 bis 1428)', Historisches Neujahrsblatt, Historischer Verein Uri, vol. 81-82, 1990-1991, p. 51-312. Online.

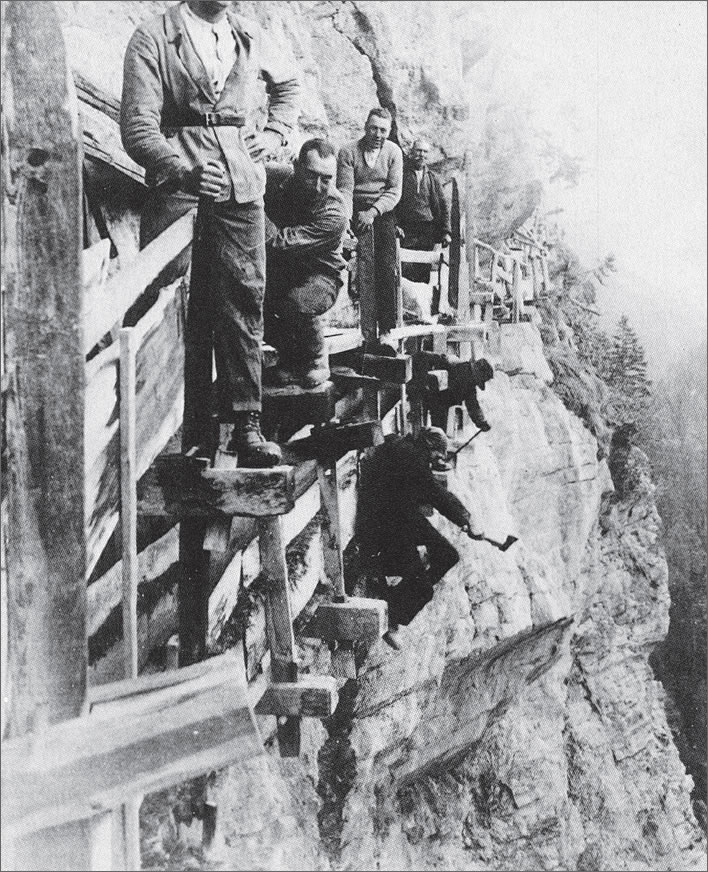

Walser at work on a Suone, a water channel in Savièse, Wallis. The planking is difficult to see, but it would be surprising if it were laid crosswise. Image: ibid.

This is an interesting illustration of the rock wall around which the Twärrenbrücke walkway ran, although the focus of interest is the Urnerloch, its replacement. Image: ND.

We are told that the walkway had to be replaced every seven years or so because the wood of the structure rotted in the damp mist that rose from the torrent – a fine biblical rhythm. We are also told that on a number of occasions, after exceptionally dramatic high water events, the river contemptuously swept the Twärrenbrücke away.

The Stiebender Steg

Once around the nose of the Kirchberg the path was still a horror, but at least a practicable horror for the strong-nerved. Not for long though. After only a few metres further our path comes to a halt, blocked by the towering cliffs on the right bank of the Reuss. The only possible continuation is on the other side of the Reuss, meaning that we have to cross the river. We know next to nothing about the bridge that was built here, who built it and how and when it was built. It must have been erected simultaneously with the Twärrenbrücke: their existence only makes sense as a pair.

For a long time it was assumed that this structure was a wooden bridge, but recent opinion has argued that it must have been a stone bridge. The locals – whether the Walser or the Ursener – were skilled at dry-stone construction, that is, building without mortar. The materials were certainly easily to hand. Perhaps it was a bridge of long timbers across stone bases. Who knows? We gather that, like the walkway upstream, it was destroyed and rebuilt, possibly more than once. It acquired the name the Stiebender Steg, the 'misting bridge'. Stiebend describes the cloud of droplets thrown up by raging water, such as you might see at the base of a high waterfall.

Whether the Stiebender Steg was wide enough to take two pack animals in opposite directions at the same time is unknown – it seems unlikely, since no one was thinking of an international transit route at the time. There would also have been no railings or parapets. For those not totally happy at heights – the Walser and the Urner seem to be immune to such things – the bridge would have been a nightmare: the exposure within the precipitous walls of the gorge on the narrow, open arch, the thundering stream rushing sideways under your feet that would steal your balance if you looked at it.

But, once over the bridge, the paths became gradually tamer – not altogether without danger – but the worst was behind you.

The pass summit

At around the time the Walser forced the Schöllenen transit with their walkway and their bridge, the pass summit acquired a new chapel and a hospice. The chapel was consecrated in 1230 in the name of Saint Godehard (960-1038) and was an enlarged version of a predecessor about which we know very little. The pass and the mountain have borne the saint's name ever since.

The existence of the Hospice at the pass summit was first mentioned in 1237. From the same source we learn that there was already at that time a considerable traffic of goods and people. If, as we think, the Walser had cracked the Schöllenen shortly after 1200, their new path achieved a rapid popularity.

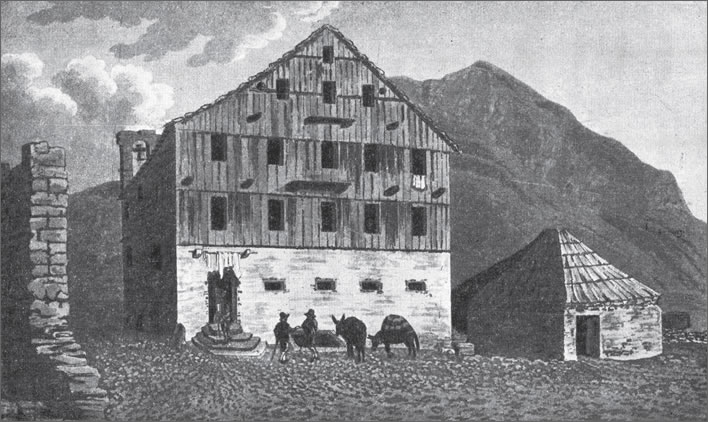

Illustration of the Gotthard Pass summit from 1785 showing some Capuchin monks (brown robes) welcoming travellers.

The Hospice and the stable block from 1790. Image: H. Keller, Wirtshaus auf dem Gotthard c. 1790 in Gruber, Eugen. 'Sankt Gotthard, Hospiz und Kult : Versuch einer knappen Darstellung der Gotthardverehrung', Der Geschichtsfreund: Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins Zentralschweiz, vol. 92, 1937, p. 278-306. Online.

The modern Gotthard Pass summit, safely wrapped in concrete and decorated with bright tin boxes, 2010. Image: ©Schweizer Luftwaffe. Online.

The hospice offered accommodation, food and stabling, protection from the alpine weather that even in summer could turn bad in an instant. Not least was the rescue of the sick and the exhausted, and the recovery of the dead, the victims of avalanches and rockfalls and those whom death had taken during their crossing – a fine metaphor. Their bodies were recovered and stored in the Totenkapelle, the 'Mortuary Chapel'. The soil around the pass is too thin and too frozen for burial, so that at an opportune moment the bodies would be transported away for a Christian interment.

The Gotthard Pass summit. In the foreground is the Mortuary Chapel. Image: Sketch by C. Wyss, 2nd half of the 18th century, Staatsarchiv Uri, Altdorf, in 'Hochmittelalter und frühes Spätmittelalter (950 bis 1428)', Historisches Neujahrsblatt / Historischer Verein Uri, vol. 81-82, 1990-1991, p. 51-312. Online.

Staying with the religious needs of travellers for a moment, there was also a chapel to Saint Anthony, located somewhere between the Twärrenbrücke and the Stiebender Steg. Its existence was first documented in 1493. We know that it was destroyed by at least one avalanche, in 1609, and then rebuilt. A service used to be held there once a month. It has now disappeared without trace.

Travellers write

The earliest documented crossings of the Gotthard Pass we possess are from travel accounts of the Master General of the Dominican order, Jordan of Saxony (1190?-1237), who crossed in 1234, and the Benedictine abbot Albert von Stade (1137?-1264) from Bremen, returning to Germany from Rome in 1236.

But the most descriptive account of an early Gotthard crossing comes around 250 years later from another churchman, Cardinal Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini (1439-1503, Pope Pius III for the last month of his life), who crossed the pass, along the Twärrenbrücke and over the Stiebender Steg in December 1471. If nothing else, Piccolomini's winter journey confirms that taking the Gotthard Pass was not just a fair-weather pursuit.

The mountains shone in old snow, but soon new snow fell. We had to cross the River Ruess on very high and narrow bridges, the wood of which was rotting. There would be no hope of saving anyone who fell. On the bridges and along the overhanging rocks we dismounted from our horses and walked on carefully. The wind blew ever stronger and drove the snow into our faces so that we could barely breathe. Even the animals lowered their heads and the wind piled up the snow on the track so that our local guides had to open a path with bars and on some parts of the route throw down bundles of branches.

At the head of the convey went three guides, who located the path with rods. Were anyone to wander off this path he would be buried in the mass of deep snow. The guides were followed by four oxen pulling sledges, then the horses, led by the reins by the stable boys, and then the rest of the convey leading their horses by the reins. No one rode, because of the danger. The Legate [Piccolomini], Bishop Campanus and all the weaker and sensitive people were transported on the sledges.

The tradition was that nervous travellers would be blindfolded along parts of the route.

By cracking the two great difficulties in the Schöllenen with the Twärrenbrücke and the Stiebender Steg, the Ursener and Urner had opened up the path for their local trade with the villages lower down the valley, all the way down to the Vierwaldstätter See and even Luzern. As far as we can tell, they were motivated by local advantages. By accident, however, they had created the greatest and most important international pass route in Europe: the Gotthard Pass.

They had forced the pass route from the top down, not from the bottom up, as one might have assumed. The consequences of the Urseners' little local innovation were almost instantaneous, like flipping the cork from a bottle of champagne.

The great European trade route

It didn't take long for the powers that be in Europe to notice what the Ursener had done. Why was the Gotthard route so important?

Because it was the single, direct route from central Switzerland to Italy. It was also the only route that would enable you to make that journey with one pass crossing – all the other routes were long detours that required travellers to cross at least two passes.

Merchants paid Säumer– porters, pack-transports (and sometimes human carriers) – by the day. Often porters would just transport goods from one village to the next, where the goods would be unloaded, stored overnight in a Sust, a transit warehouse, and then taken to the next village by another porter, who would use his own pack animals. On each leg of the journey the porter earned money, the village earned money and the feudal owners earned money. Transport costs were a major factor for every trader. But despite its difficulties, the Gotthard Pass flourished for most of the time and took traffic away from the other passes.

Without getting into a tedious analysis of traffic over all the other transalpine passes – the Gotthard's competitors, if you will – a little bit of simple data will show just how important the opening of the Gotthard was. If we measure the approximate distances from Zürich to Milan, we find the following transit distances:

— via the Simplon: 400 km;

— via the San Bernadino: 300 km;

— via the Gotthard: 240 km.

That is only half the story, though, because the Gotthard had another immense advantage over its competitors: from almost anywhere that mattered to north-south traffic, from Basel or anywhere along the Rhine that flows east-west across the north of Switzerland and the south of Germany, the Gotthard could be reached by water. Travellers and traders would arrive by river at Luzern, cross the Vierwaldstättersee, the Lake of Lucerne, and arrive at the harbour of Flüelen/Altdorf at the foot of the Gotthard Pass.

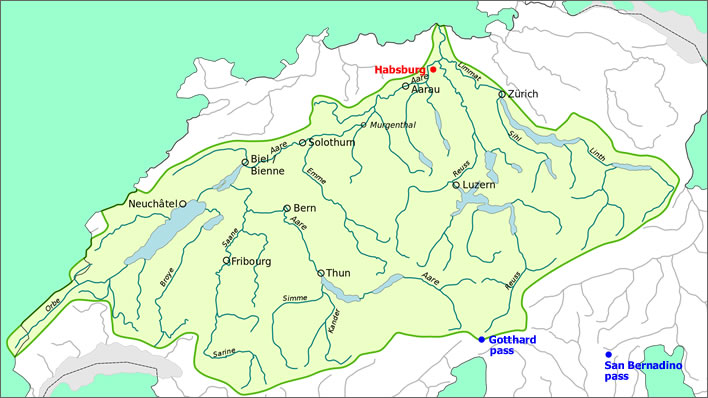

The three great river systems that drain nearly all of Switzerland: the Aare (left), the Reuss (middle) and the Limmat (right). Having picked up its two great tributaries the Aare flows northwards to meet the Rhine (not shown), that flows here east to west along the Swiss border. The Habsburg castle is situated almost exactly at the junction of the three rivers. For international traffic the route to the Gotthard Pass is much shorter than the routes to its competitors in the east, such as the San Bernadino pass. Four rivers have their watersheds in the Gotthard region (clockwise): the Aare, the Reuss, the Rhine and the Rhone. Image: based on Wikimedia.

From that point they had only 180 km of land journey ahead of them to get to Milan. Some of those kilometres were tough, but time was money, then as now. In the reverse direction, south to north, the river passages were an effortless coasting downstream. It was possible to travel between Luzern and Rotterdam and all points in between along the great waterways of Europe.

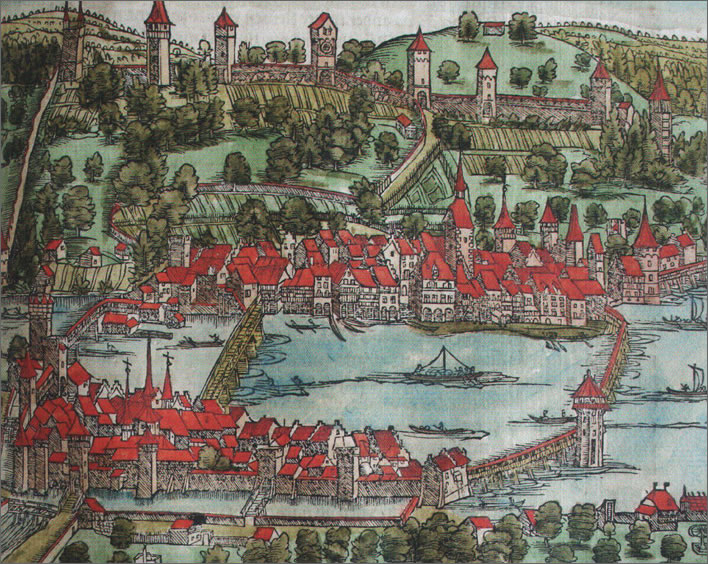

The potential of water transport was the great advantage of the Gotthard route. Luzern, on the junction of the Reuss with the Vierwaldstättersee, became one of its most important nodes. This is a drawing of Luzern from Johannes Stumpf's Schweytzer Chronik of 1546, highlighting the amount of waterborne traffic through the town. Image in Baumgartner, Christoph. 'Salz in Luzern: Eine Untersuchung des spätmittelalterlichen und frühneuzeitlichen Salzwesens der Innerschweiz', Der Geschichtsfreund: Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins Zentralschweiz, vol. 162, 2009, p. 1-106. Online.

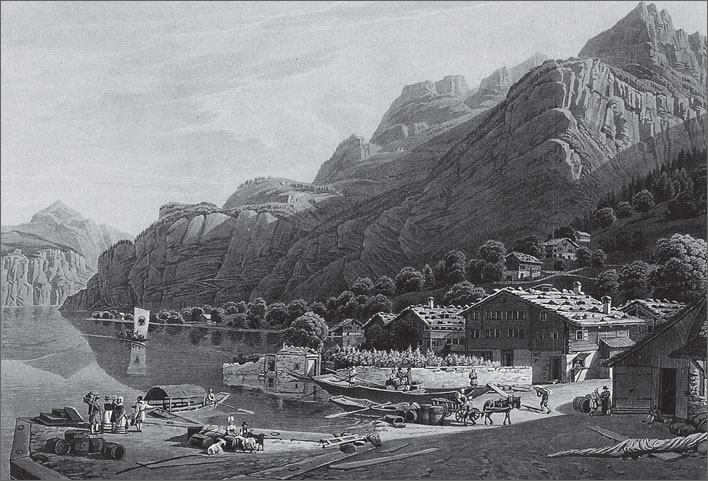

At the opposite corner of the Vierwaldstättersee and at the foot of the Gotthard route was the port of Flüelen.

Top: the port of Flüelen around 1800. Image: 'Hochmittelalter und frühes Spätmittelalter (950 bis 1428)', Historisches Neujahrsblatt / Historischer Verein Uri, vol. 81-82, 1990-1991, p. 51-312. Online.

Bottom: The old Sust of Flüelen around 1906. Every stopping point on the Gotthard route had a Sust, which offered temporary storage for goods in transit and reloading between pack transports. Image: ibid.

A modern image of the Sust in Silenen on the Gotthard route, ND. Image: ibid.

The region around the Vierwaldstättersee, up until then a forgotten corner at the foot of the central Alps suddenly sprang into life and became a transit route of the first order. The town of Luzern, sited at the point where the Reuss flows into the Vierwaldstättersee, was founded around 1200 - just about the time the Walser in Urseren were building their bridges in the Schöllenen. Once the Gotthard became a viable transit route, Luzern became a focus for the trade along this new north-south axis.

The age of trade

There is a much greater, underlying factor in the development of the Gotthard Pass: the development of trade in the Middle Ages. From the High Middle Ages (c.1000-c.1300) Europe experienced a great explosion of culture and civilisation. As we have already mentioned, the climate was warmer during those times, a factor that few historians really considered until about 50 or so years ago. We mustn't overstate the importance of that factor, but it seems reasonable to take it as the background to all the other changes that took place.

There was a population explosion in most parts of Europe. Along with which went an enormous improvement in agriculture, both in techniques and in area. Trees were felled and the rural landscape was created that we are familiar with today. Whether the farming improved to feed an expanding population or the population grew because of better food – well, who can tell? Probably both.

Agriculture not only produced more, it specialised in various ways: grains, flax, wool, sheep, goats; dairy and meat products, beer and wine. Such diversification was only possible when there was trade. How many pullovers can one sheep farmer's family wear? Trade is the great engine of human progress that lifts the feet of men out of the soil they must till.

Wherever there has been a great civilisation, there has been trade. Do we need to list them all? At almost every ancient site it is the archaeologist's daily bread to find artefacts that have arrived from elsewhere, sometimes from great distances across land and sea routes.

By the time the Gotthard Pass came into existence, Europe was bustling with trade. Every navigable waterway, every road that could bear an ox-cart or a donkey was carrying goods back and forth. Great markets had been established as trading exchanges: in the Île-de-France, in Champagne – which even gave its name to the important 'Champagne fairs' of medieval times – in Alsace and along the Rhine. Roads were improved, bridges were built. The same thing was happening south of the Alps in northern Italy, along the broad, rich alluvial plain of the Po. The development of both the Gotthard and the Simplon passes was driven by the development of markets in northern France and Germany that needed a connection with the flourishing cities of northern Italy, particularly Milan.

The Gotthard Pass

One of the most important trade nodes came into existence in northern Switzerland. There the navigable Rhine meets the navigable Aare, which in turn meets the navigable Reuss. An important trade fair was established at Zurzach, close to the union of the two great waterways. Traders could use the rivers or the paths alongside them. Nearly a hundred towns were founded along the Aare alone during this period of growth. Towns, too, enabled specialisation among craftsmen and encouraged consumption by people who were no longer self-sufficient.

Before the Gotthard was opened, trade with Italy used to go across the Simplon pass in the west or the San Bernardino pass in the east. Traders arriving in Luzern might look southwards at the peaks of the St. Gotthard massif – the St. Gotthard was thought to be the highest mountain in Switzerland at the time – but could go no further, unless they dared the narrow tracks to bypass the Schöllenen gorge. Once the Gotthard Pass had been created the situation changed completely – the Gotthard became the route of choice: the shortest, the fastest route to and from Italy.

Contemporary Customs documents give us a good idea of the variety of goods that were transported along the Gotthard route.

The remains of the customs bridge in Göschenen, ND. Transports were obliged to cross the bridge over the Reuss in Göschenen where they would be inspected by a customs officer and customs duties exacted. Image: ibid.

From the north we find metal ores, linen, ceramics, willow sticks, goat and sheep leather, sheepskins, bales of wool, woollen cloth and heavy loden cloth, pewter, cheese, milk products and salted pork. During the early Middle Ages the flourishing population of Lombardy had expanded beyond the local ability to keep up with demand, particularly for food, presenting an opportunity that the flourishing producers of the north were happy to seize, particularly now that the Gotthard was open.

In the other direction we find laurel, fustian cloth, cotton, all kinds of herbs and spices, wax, steel, red madder dye, Baghdad indigo, horses, oriental silks, iron tools, corn, peas and beans, flour, salt, chestnuts, oats and wine.

Salt, essential to life, was one of the key goods transported across Europe. It went in both directions across the Gotthard in large quantities.

Weights and measures for salt, 18th century. The stacking brass weights weigh altogether 490 g, close to the modern German Pfund and the imperial 'pound'. They consist in total of eight parts – the smaller elements are still stacked in the lefthand container. The flat copper pan is inscribed 'salt measure'. Image: Historisches Museum Luzern (HMLU 01908; 01881.01) in Baumgartner, Christoph. 'Salz in Luzern : eine Untersuchung des spätmittelalterlichen und frühneuzeitlichen Salzwesens der Innerschweiz', Der Geschichtsfreund: Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins Zentralschweiz, vol. 162, 2009, p. 1-106, Abb. 14. Online.

The 'civilising' of the northern countries in the Middle Ages combined with an increase in the circulation of money led to a growing market there for the luxury items and foodstuffs that the south could supply. Innovations and manners spread with trade. The people of the Byzantine Empire stuck forks into their food; this habit and the requisite utensil spread to Venice and then across the City states of the rest of northern Italy and thence inexorably into the culture of the north. There was a time when the banqueting nobles of Europe would toss their chomped cutlets back into the communal pot; before too long they were ordering gold cutlery, fine crockery and considering appropriate table decorations. Trade carries more than goods, it carries culture.

Pass management

Once the Twärrenbrücke and the Stiebender Steg had opened up the Gotthard route to commercial traffic, the work to transform it into a viable pass could begin. The villages along the route, up until then destined to scratching a meagre existence from a hard environment, acquired a new source of income from the customs duties they could raise from the transit trade, the fees the locals could earn as guides and as porters, taking convoys of pack animals laden with goods from one stage to the next. Some porters only travelled over a particular stage from one village to the next. They would also help in the upkeep of the track on their stage. Others travelled long stretches and paid extra fees to the villages through which they passed for the maintenance services the community provided. The entire stretch from Luzern to the Italian border could take between five and seven days.

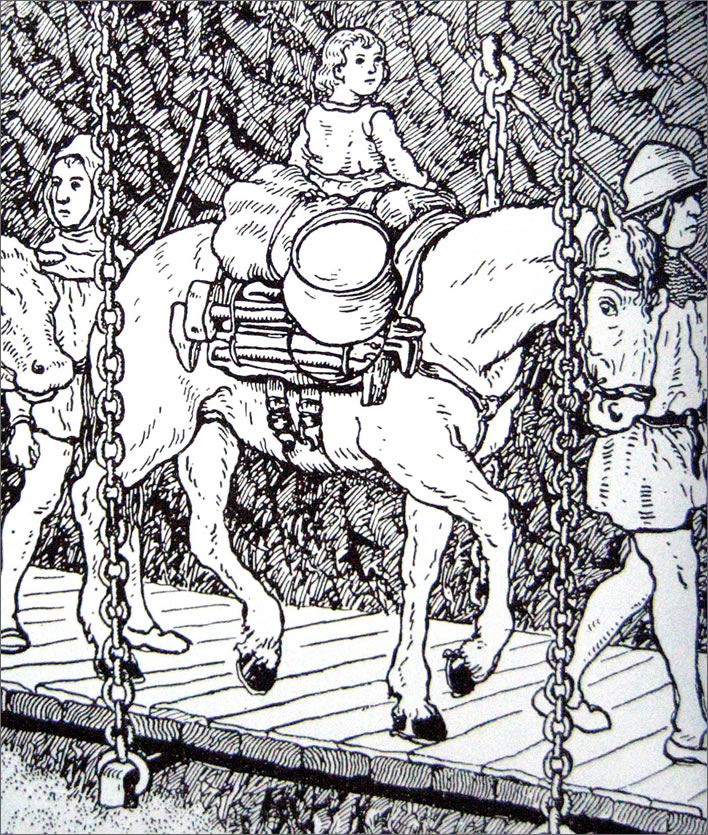

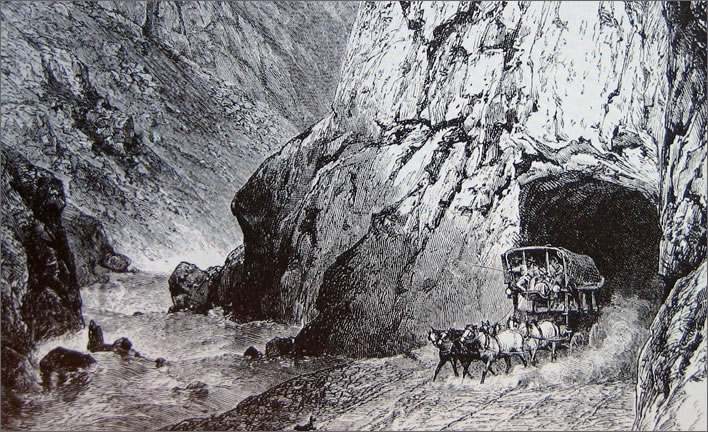

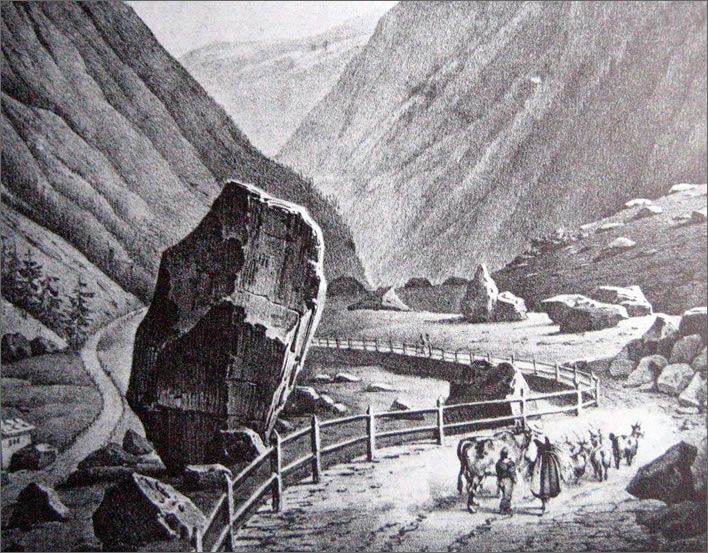

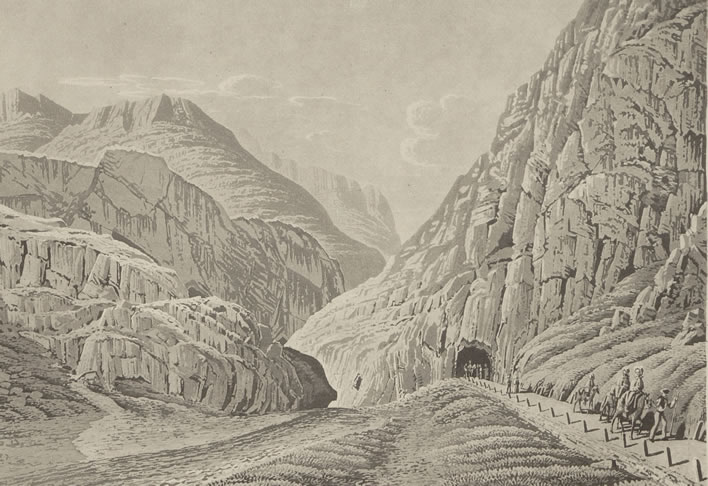

A romantic bucolic image of pack transports at the southern end of the Urnerloch in 1790.

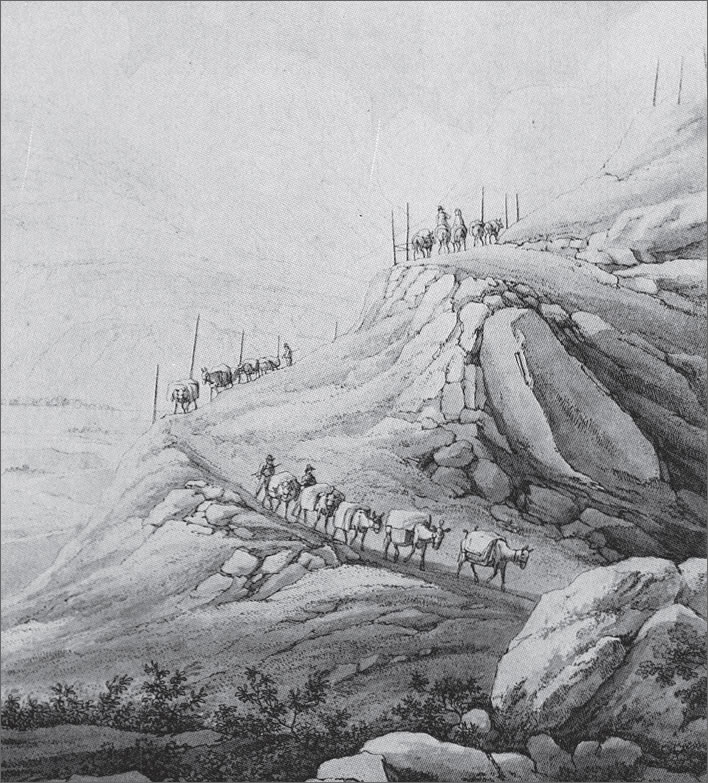

An illustration of pack transports in one of the serpentine sections of the Gotthard route from around the end of the 18th century. Note the use of long snow poles on the downhill side of the track to mark the path in winter. Image: Engraved by W. Rothe from a drawing by I. G. Jentzsch, Zentralbibliothek Zürich, in 'Hochmittelalter und frühes Spätmittelalter (950 bis 1428)', Historisches Neujahrsblatt / Historischer Verein Uri, vol. 81-82, 1990-1991, p. 51-312. Online.

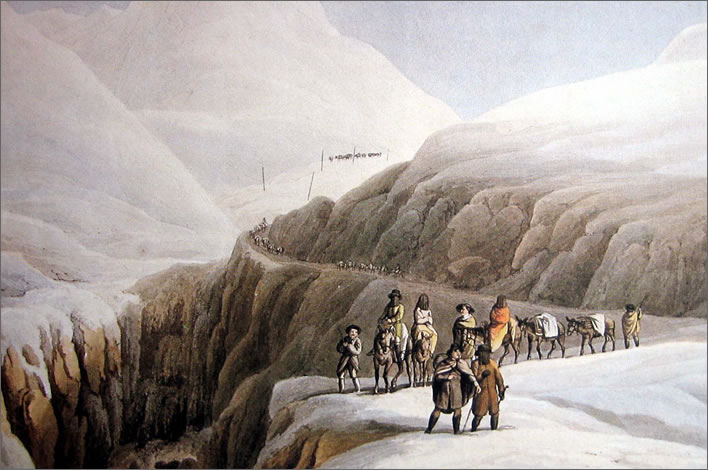

A group of travellers on the Gotthard route in winter, late 18th century, in the background some pack transports. Some of the travellers have covered their faces with black muslin veils, a common protection at the time against snow-blindness and sunburn. Image: Engraved by W. Rothe from a drawing by I. G. Jentzsch, PTT-Museum, Bern.

High drama in the snow and ice on a narrow path above the chasm. Note the good representation of that Gotthard feature, the winter wind.

In return, the locals had to secure that income by improving and maintaining their part of the pass route. Tracks were broadened and roughly paved, some parts wide enough for counterflow traffic. Routes damaged by rockfalls or blocked by fallen trees were rapidly cleared; during the long winter months – eight months of the year in these parts –snow was cleared away and paths were broken through on a daily basis. Clearing snow was such a pressing task for much of the year that specialist workers (Ruttner in German, Rottori in Italian) were employed to do it. Only by continuous maintenance efforts could the locals sustain this wonderful new source of income.

A photograph of the remains of a carefully paved track in the climb up to the Gries glacier (Goms) above Rothärd at an altitude of 2,330 m in Wallis. The flat stones give stability and the small stones give grip in wet and icy conditions. Exactly the same technique was used on the pack route over the Grimsel pass. The photograph was taken in August 1963, shortly before the track was wrecked in the construction of the Gries dam. Image: Aerni, Klaus, Benedetti, Sandro. 'Von der Teufelsbrücke zu "AlpTransit"', Archäologie Schweiz: Mitteilungsblatt von Archäologie Schweiz, vol 33, 2010. p. 64-69. Online.

The remains of a pack route between Silenen and Amsteg. Image: 'Hochmittelalter und frühes Spätmittelalter (950 bis 1428)', Historisches Neujahrsblatt / Historischer Verein Uri, vol. 81-82, 1990-1991, p. 51-312. Online.

Remains of a pack route in Urseren. The upright stones along the edge of the track are usual in places where the ground falls sharply away. Image: Xaver Grueter.

Remains of a pack route near the Gotthard Pass summit. Image: Carlo Pisani, swissinfo.ch, 2017.

Remains of the pack route between Hospental and the pass summit, 2010. Image: ©Kilian T. Elsasser, in Elsasser, Kilian, Häfliger, Toni, 'Verkehrslandschaft Gotthard', Werk, Bauen + Wohnen, Band 97, Heft 9, 2010, p. 26-31. Online.

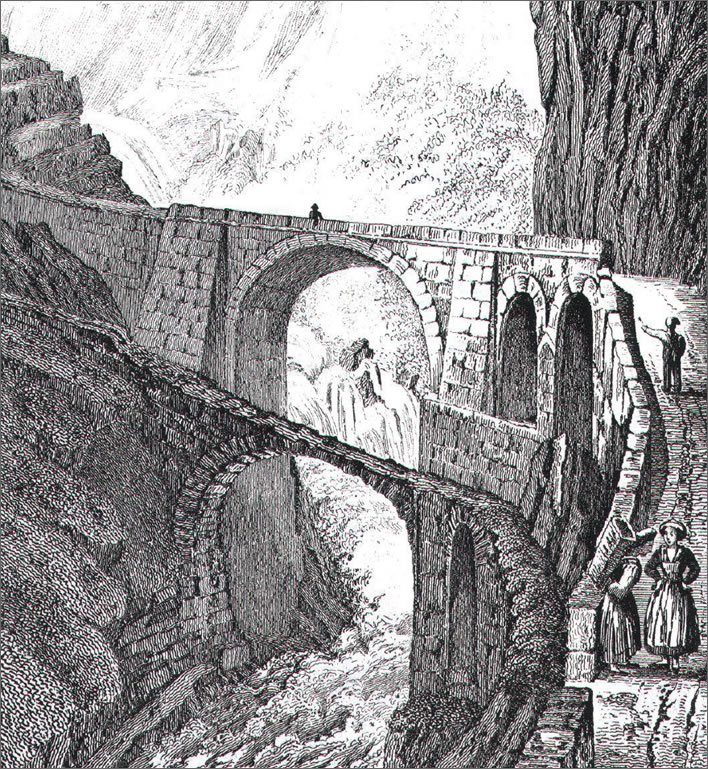

The Häderlisbrückewith its notable three arches. This stone bridge was built in 1649 to replace a wooden bridge. The bridge was an important marker on the route through the Schöllenen. The stone in the river on which the bridge rests marked the border between the Göschener and the Ursener side. The responsibility for the upkeep of the route changed here from the Urner (downstream) to the Ursener (upstream).

Top: Muheim, Jost (1837-1919), Häderlins[sic]-Brücke mit Säumern und Pferden, 1892. Image: SBB-Archiv.

Bottom: The original stone bridge was was washed away by a storm in August 1987. The bridge here is an 'exact replica' erected in 1991. Image: ©Paul Egger, September 2011.

The villages on the route built Susten, transit warehouses, to store goods overnight before they were taken on the next stage of their journey. They built stables for pack animals and other animals being transported. Inns sprang up to cater for for the passing and the overnight trade.

Prosperity arrived along the route. The various levels of the feudal hierarchy – the ultimate owners of everything in Europe – took their slices of this prosperity, but also had to earn it by playing their part in the management, organization, maintenance and policing of the route. It is a universal truth: the successful parasite does not kill its host.

Security was key. In 1283 the great Habsburg king and emperor Rudolph I, the original architect of the Habsburg dominance of the Gotthard region, wrote from his army encampment in Pruntrut (Porrentruy) near Basel an appeal to the traders of Italy encouraging them to use the Gotthard. He had heard that robberies were taking place and assured them that he would make the route secure. Coming from Rudolf, the dominant figure of the time, the assurance was weighty –he was not a man you trifled with. He had, he wrote, summoned to him all the nobility that had rights to the territory from Lothringen (Lorraine) to the Alps and commanded them that every trader who paid the customs duty should receive a safe passage. If, despite that, an attack took place, the victim would receive a full reimbursement of his losses.

The Habsburgs

Piece by piece, the towns and areas along the Gotthard route fell into the hands of the Habsburgs. The great rivers, the Rhine, the Aare, the Reuss and the Limmat came together in their home territory. The Habsburgs controlled southern Germany and Alsace, the lowlands around the castle in the north of Switzerland from which they took their name and the territories on the route to the pass itself. By clever manipulations and feudal good luck in inheritance, breeding and marriage they succeded in joining up these transit territories.

The dynasty took their possessions seriously. A large part of their income derived from customs charges and taxes on trade: bridge crossings, mooring points, road tolls and, of course, on the portered convoys transporting goods over the Gotthard. As feudal rulers the Habsburgs obliged their underlings to maintain tracks and protect the travellers on them, as we saw in the example of Rudolph I.

The agents of security were already at hand. Driven by poverty, that constant companion of mountain life, in their younger days many inhabitants of the mountain villages had served as mercenaries in foreign armies. As a result they were completely capable of dispatching any robbers who threatened their lucrative trade routes.

The Habsburg water routes grew in importance. The market at Zurzach, located at the apex of these waterways, attracted sellers and buyers from far and wide. It was first mentioned in the 1200s and grew rapidly to compete on equal terms with the markets in Basel and Zürich, its speciality being fabric from all over Europe as well as horses. The report of a fire that laid waste to Andermatt in 1766 gives us a hint of the commercial popularity of Zurzach and of the Gotthard Pass even as late as then:

On the 9 September, at two o'clock in the morning, a fire broke out in Andermatt. The strong wind spread the fire quickly. Many people from different places, Germany and France, but most of them from the Zurzach market and from Italy were staying there overnight and did what they could to rescue their people and goods. They lost nothing, whereas the inhabitants lost everything.

The Habsburgs lost control of the three original cantons in 1291, when the seed crystal around which the rest of the country would gradually accrete was created. The fantasy drama of that moment is recreated in Schiller's Wilhelm Tell, the action of which takes place in the lower Gotthard region. It is no accident that the three founding cantons, the Ur-Kantone, cluster around the Gotthard. Did the creation of the Gotthard Pass by the farmers of the Urserental in turn create Switzerland? Some have said that the Gotthard was the heart of the Swiss Federation and that Switzerland was in reality a 'pass-state', a country defined by its passes. Following this reasoning, the real founder of Switzerland was not the mythical Wilhelm Tell and brave little Walter, his son, but the unknown men who built the Tärrenbrücke and the Stiebender Steg.

The Teufelsbrücke

Modern technocrats might call the Twärrenbrücke and the Stiebender Steg 'proof of concept' developments. The combination, despite all its terrors as well as all the frights of the rest of the route, worked brilliantly well – not only for a few years either: the Twärrenbrücke would serve its purpose for 500 years and the Stiebender Steg for 400. But the weaknesses were unmissable. Both structures were vulnerable to the bad moods of the Schöllenen and its instrument of destruction, the angry Reuss. Both structures needed regular repair and renewal.

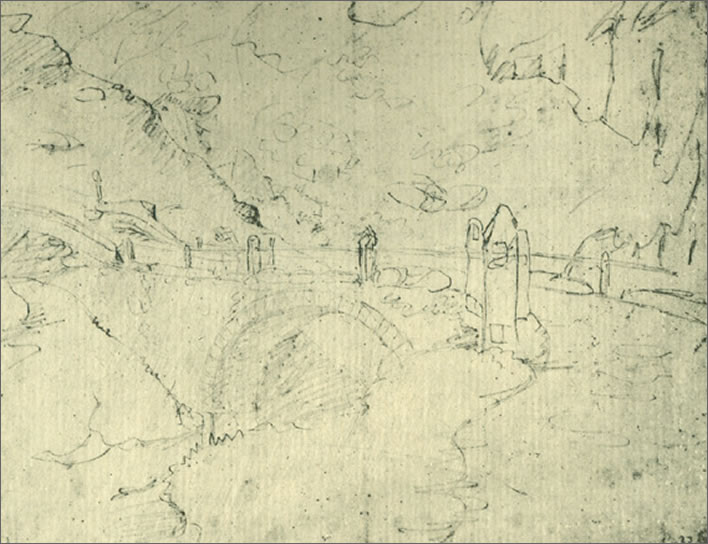

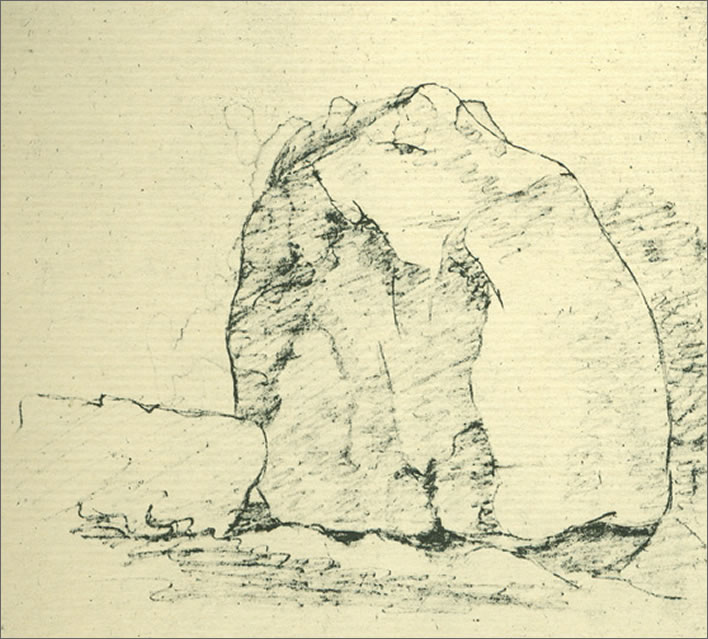

A sketch of the Teufelsbrücke by Johann Wolfgang Goethe from the first of his three journeys along the Gotthard Pass (strictly speaking four journeys, since in 1775 he went up and down the route). The representation of posts and railings in his sketch is interesting and credible, since someone in a hurry does not make such things up, whereas professional landscape artists do what is necessary to get the desired effect. Image: 'Zeichnung Goethes: Teufelsbrücke Bezeichnet: "23 Teufels Brücke"' in Koetschau / Morris, Tafel 10a; Corpus I, Nr. 127. Online.

The Teufelsbrücke in summer 1776, a year after Goethe crossed it for the first time. The railings that Goethe sketched are there. Plenty of drama but quite faithful to the scene, even down to the snow posts on the path leading to the Urnerloch. Unfortunately the height of the bridge has been greatly overstated. Image: Claude-Louis Chatelet (1753-1794), artist in 1776 (original lost), Louis-Joseph Masquelier (1741-1811), engraver in 1778, in Weber, Bruno. '"Aber die Kluft ist schauerlich, die sie umgiebt": elf Variationen über die alte Teufelsbrücke der Schöllenen (1595-1888) in druckgraphischen Ansichten von 1707 bis 1863'. Historisches Neujahrsblatt / Historischer Verein Uri, vol 98, 2007. Online.

There is a reason that Joseph Mallord William Turner, (1775-1851) is regarded as a great painter, if only for his ability to capture the drama of landscapes and seascapes. We presented his representation of The Schöllenen Gorge from the Devil’s Bridge above. Here are two of his impressions of the Teufelsbrücke.

Top: The Devil’s Bridge and Schöllenen Gorge, 1802. Image: ©Tate, London. Online.

Even more drama a year later: The Devil’s Bridge, St Gothard c.1803–4. Image: Tate, London. Online.

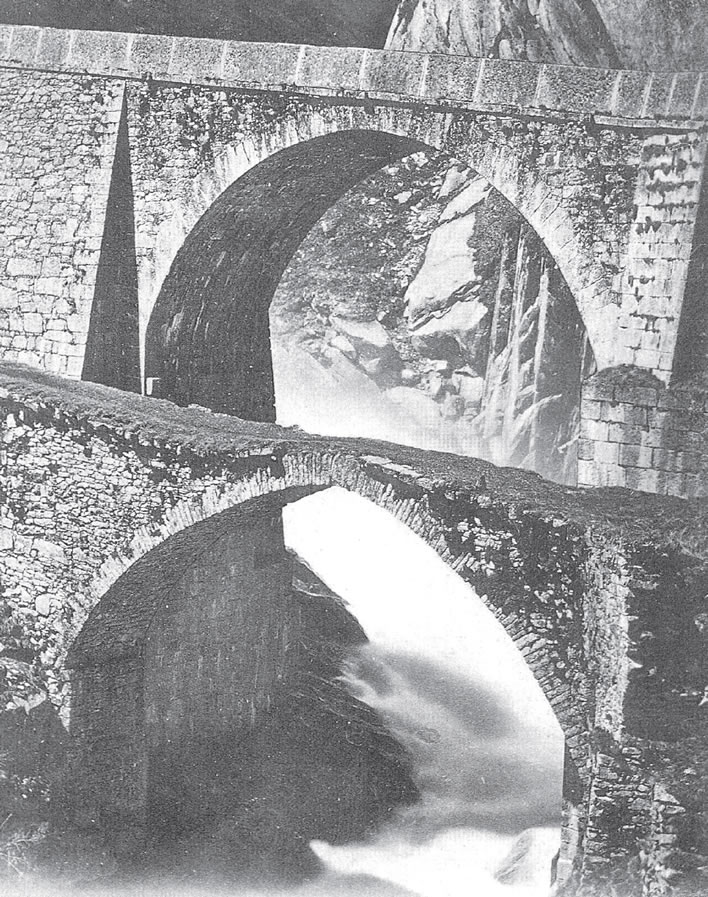

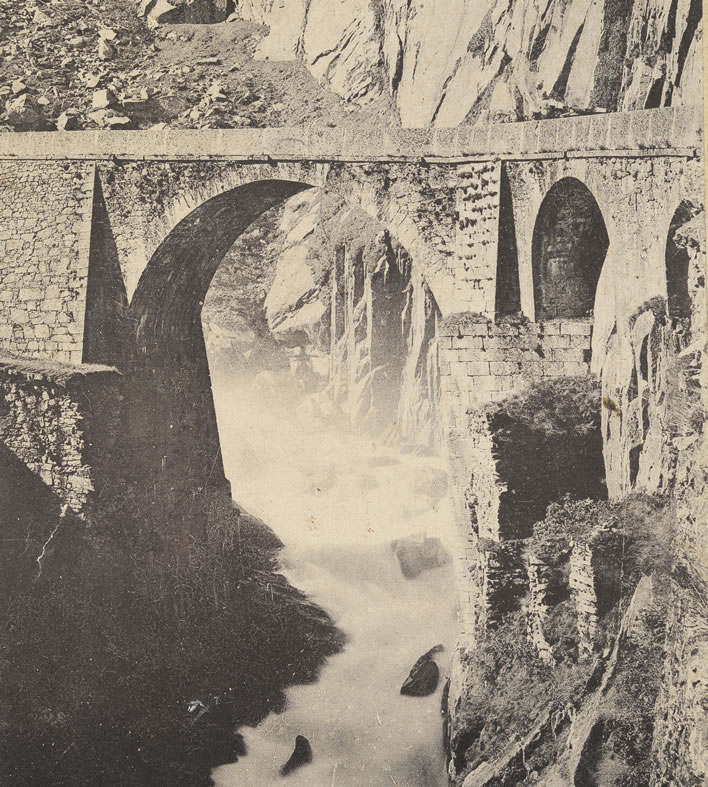

The Stiebender Steg was the first to be replaced, by a stronger, wider and higher bridge. It is thought this occurred in 1595. The replacement was definitely a stone bridge, built without mortar and thus requiring a strongly curved arch in order to stay up. The bridge was about 2.7 metres (9 feet) wide, just enough for two pack animals to pass. Its highest point was about 24 metres (80 feet) above the torrent and the arch spanned a distance of around 17 metres (56 feet).

The locals had respected their old Stiebender Steg– it had brought them an income, after all – but the new bridge acquired the name Teufelsbrücke, the 'Devil's Bridge'. The process that led to the use of this name is not really understood. We have neither space nor inclination to attempt to disentangle all the mythological accretions that formed around this bridge and the Devil's participation in its construction.

To outsiders using the Gotthard Pass the bridge was certainly frightening: it was higher than its predecessor, had no parapets and at some period there were some stone posts as edge markers. When it wasn't covered in snow, it might be iced over from the permanent mist of the thundering Reuss, at the very best of times it would be wet and slippery. At some time after 1600, therefore, the bridge acquired its brandname and would fulfil its function under this name for a further 230 years. The name would be a useful handle down the years for tourists to use in describing their entertaining crossing.

A star is born: the branding of the Teufelsbrücke

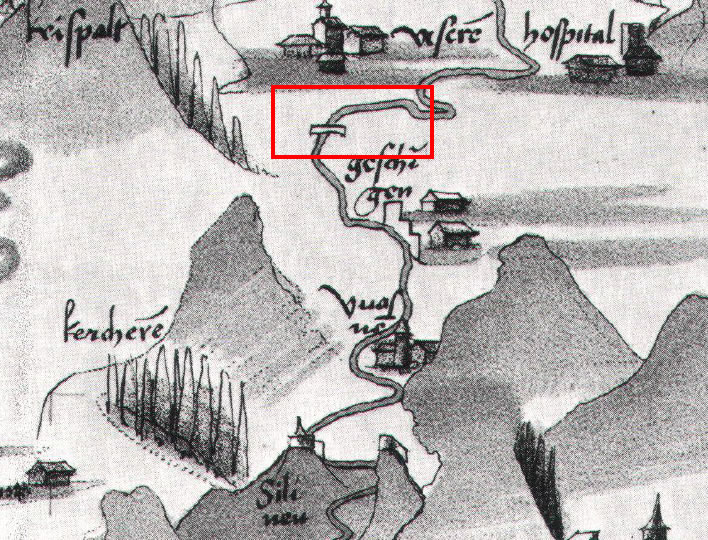

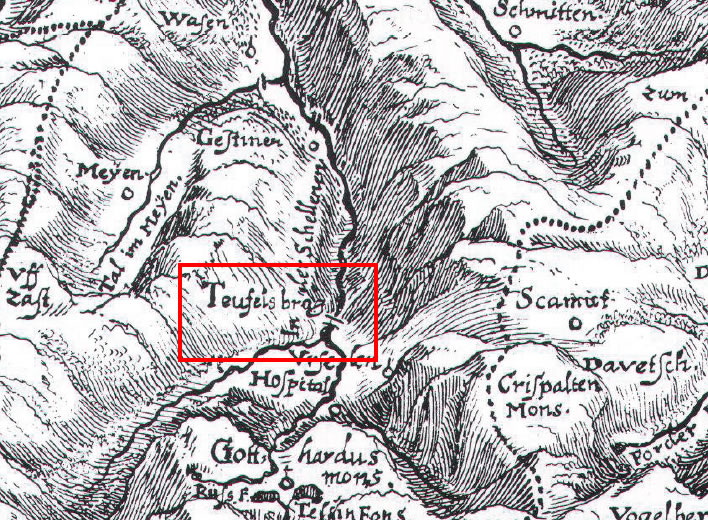

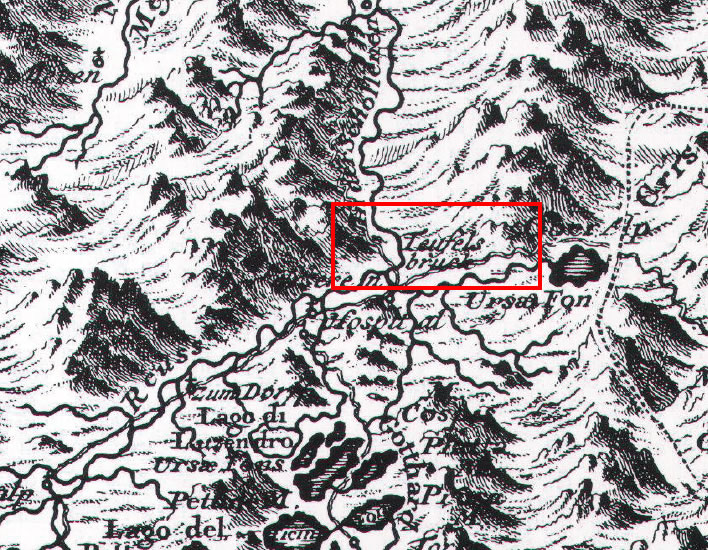

The chronology of the brandname Teufelsbrücke can be roughly traced through the use of the name on historical Swiss maps. It is clear that whether the bridge is the Stiebender Steg or its 1595 successor the Teufelsbrücke the structure itself was always worthy of note by cartographers. Once the colourful brandname appeared it was taken up with alacrity.

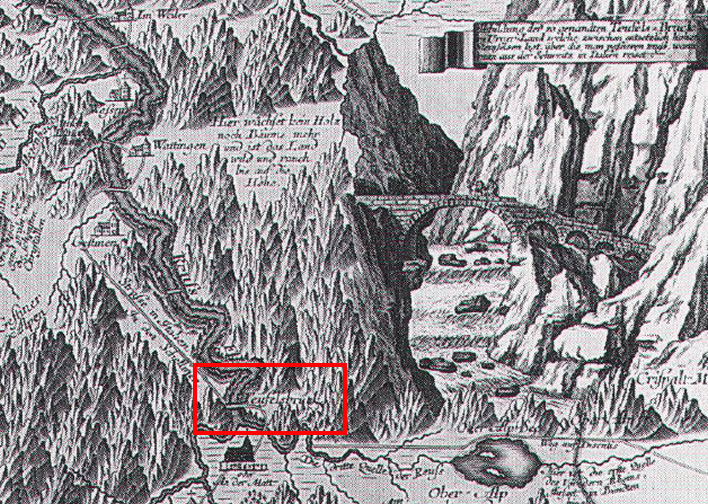

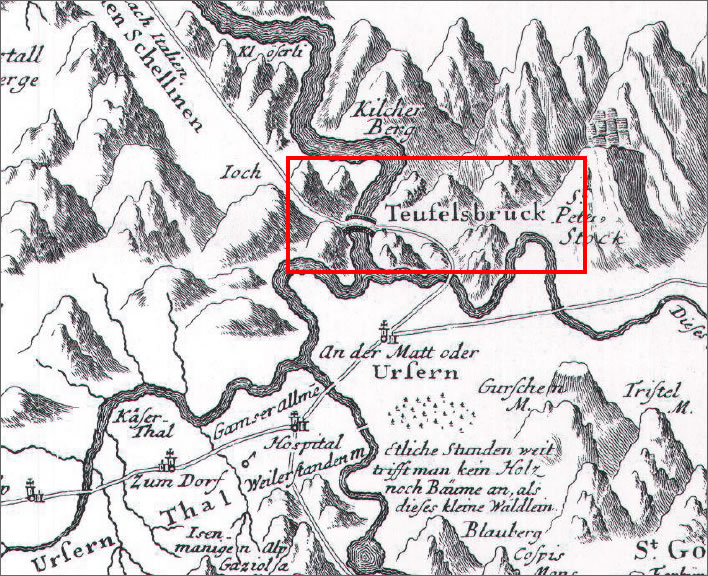

1495/97, the Türstkarte. The bridge marked is the Stiebender Steg, clearly worthy of note but nevertheless anonymous. There is no mention of the Twärrenbrücke.

1513, the oldest printed map of Switzerland. The present day Andermatt is labelled Urseren; the Stiebender Steg is still worthy of note yet anonymous.

1657, the map by Hans Conrad Gyger. The Teufelsbrücke (built 1595) is drawn and named.

1720 version of Johann Jakob Scheuchzer's renowned map of Switzerland. The Teufelsbrücke is drawn and named. The Urnerloch had been created in 1707 but is not marked.

1756, the map by Gabriel Walser (1695-1776), showing the location of the Teufelsbrücke, together with an illustration and a note, so great has its fame become by now. The Urnerloch is not named and not identifiable in the confusion of the route at this point.

1768, another map by Walser, once again with a clear designation of the Teufelsbrücke, but yet more Urnerloch confusion.

The Teufelsstein

Since the devil had clearly been busy in the Schöllenen, the name Teufelsstein, 'Devil's Rock', was applied to a large boulder perched along the route near Göschenen. Although nothing to do directly with the opening of the pass, it has become part of Gotthard mythmaking and so deserves a mention.

A view of La Pierre du Diable, Vallee de la Reuss and the Gotthard road from around 1840(?). Image: Lithograph by Joseph(?) Langlumé from an original by Édouard Pingret (1785-1869).

The boulder is about 13 metres (40 feet) high and weighs around 2,000 tons. The fairy story tells us that the Devil was intending to heave the rock at the newly-built Teufelsbrücke (don't ask why, there is a limit…), but when he put the stone down a little old lady quickly scratched a cross on it. Satan could no longer move the rock, so he left it where it was and went off back to Hell. The Teufelsstein passed into legend, as such things do, and became one more marker on the Gotthard transit. Goethe, on his first journey through the pass in 1775 has left us a sketch of it:

Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Teufelsstein, 1775. Image: 'Zeichnung Goethes: Teufelsstein Bezeichnet: "23 Juni Teufels Stein"' in Koetschau / Morris, Tafel 9c; Corpus I, Nr. 123. Online.

A little over a hundred years later, in 1885, the farmer on whose land the Devil had put the boulder down sold the rock to a chocolate manufacturer in St. Gallen for 80 CHF– about the price of a cow then. The chocolate company painted the boulder brown, adding an inscription in bright yellow letters of cheerful directness: Schokolade Maestrani ist die beste, 'Maestrani chocolate is the best'. The advertisement was there for every train passenger to see for 40 years. 80 CHF well spent. In the Second World War a hole was drilled in the top of the rock by a local patriot for the 1 August National Day and a Swiss flag stuck in it. At some time another hole was drilled and the flag of Canton Uri was added.

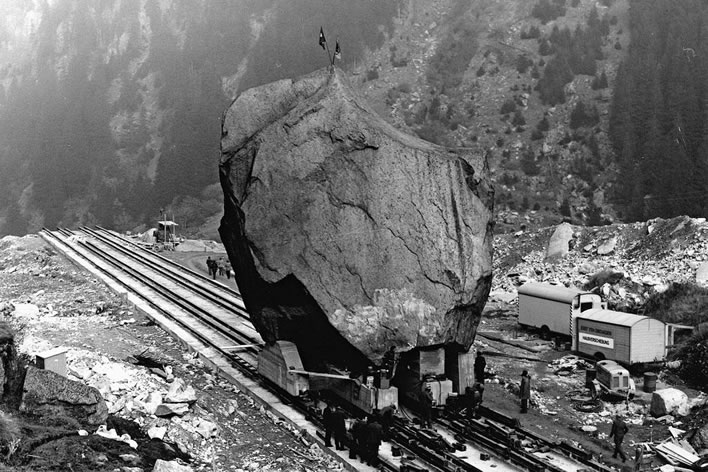

In 1973 it became clear that the Devil had carelessly set down his rock just on the spot where the portal for the new road tunnel should be. Despite all the insults the rock had suffered at the hands of humans, by modern times this Devil saga had become so pervasive that instead of just blowing the boulder to smithereens as the builders would have done with any other rock, value 80 CHF, the Swiss taxpayer stumped up 335,000 CHF (a lot of money then) to move the block of granite 127 metres (400 feet) to the north, out of the way of the tunnel portal to its current position at the side of the approach road.

The Teufelsstein on the move in 1973, heading north away from the future road tunnel entrance/exit. Image: Bild: Staatsarchiv Uri. Online NZZ.

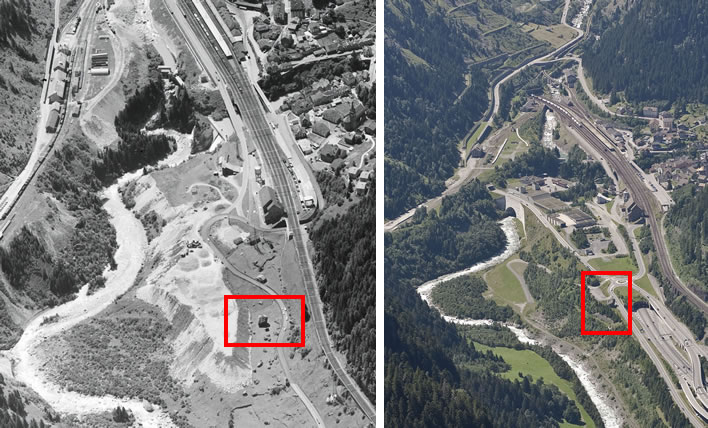

Left: aerial view of the Teufelsstein in 1963. The position confirms the accuracy of the early engraving, with the stone in the curve of the road; even the lean of the stone was well represented. Image: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Fotograf: Comet Photo AG (Zürich) / Com_F63-00891 / CC BY-SA 4.0.

Right: an aerial view in 2007, with the stone safely out of the way of the road tunnel after its relocation in 1973. (Use the large building next to the railway lines as an orientation aid.) Image: ©Schweizer Luftwaffe 2007.

The Teufelsstein in 2006, offering little distraction for travellers leaving and entering the road tunnel on the left. Image: ©Roland Zumbühl.

The Urnerloch

After the Teufelsbrücke was built in 1595 the Twärrenbrücke would do its duty for about another century. It was now, however, the weakest partner in the pair – as we have already noted, not only did the wooden walkway rot and have to be renewed frequently, the structure appears to have been frequently washed away by the Reuss. For the locals, who had to maintain it, the Twärrenbrücke became just too expensive. The solution was as innovative for its time as the Twärrenbrücke had been in its: the construction of the first alpine road tunnel.

In 1707 the Twärrenbrücke had been washed away yet again, so the government of Canton Uri contracted Pietro Morettini, from the Tessin, to cut a hole through the nose of the Kirchberg from one side to the other. It took Morettini's workers eleven months to do this, ending up with a 60 metre (200 feet) long tunnel that was 2.1 metres (7 feet) wide and 2.4 metres (8 feet) high (riders had to dismount). It was an instant success and acquired the name Urnerloch, the 'Urner Hole' (German had not yet acquired the word 'tunnel', which they would have to borrow from English, who had in turn borrowed it from old French ton(n)el, meaning 'barrel'). Over the years the Urnerloch was extended and is still there, in spirit at least, in the name of the motorway and rail tunnel that replaced and obliterated it.

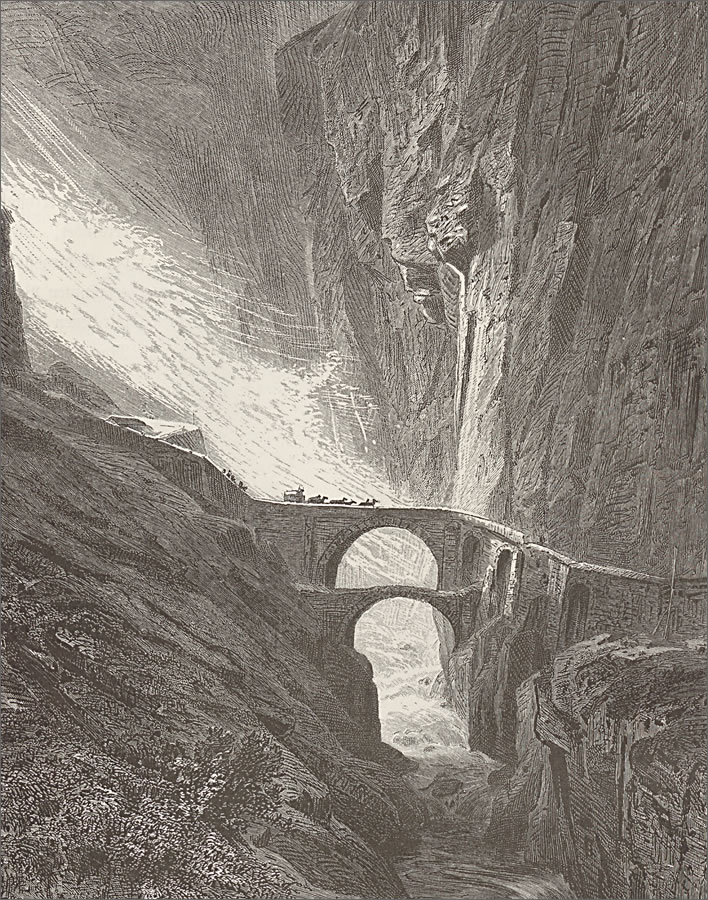

J.M.W. Turner's sense of drama is at work in this image of the Urnerloch, presumed to be from around 1806. The note to this mezzotint on the Tate Gallery's website is careless and incorrect, as readers of the present article will immediately recognise: 'The present view is from the Schöllenen Gorge, looking north along the valley of the Reuss above Goschenen.' If Turner had been 'looking north' there would be no towering mountains in the background, he would have been looking at the relatively low lands of northern Switzerland. Since, acording to the Tate, Turner had already illustrated the 'Little Devil’s Bridge'[sic] in the same series, a few minutes' stroll upstream would have brought him to the Urnerloch. Can there be any doubt that the view shown here is of the north portal of the Urnerloch, that Switzerland is at our back and that Turner is looking south to the high Alps and the pass towards Italy in the south? Turner himself titled his work absolutely accurately as 'Mt St Gothard', which is indeed the mountain shown in the background, looking south. Image: ©Tate. Online.

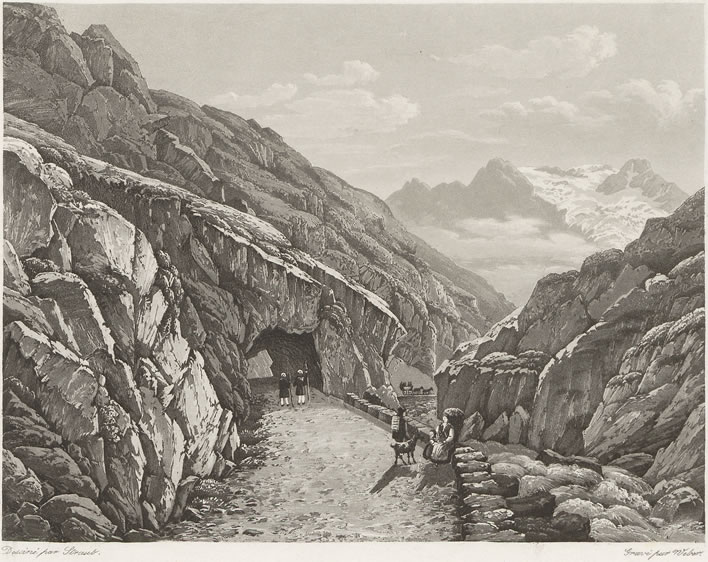

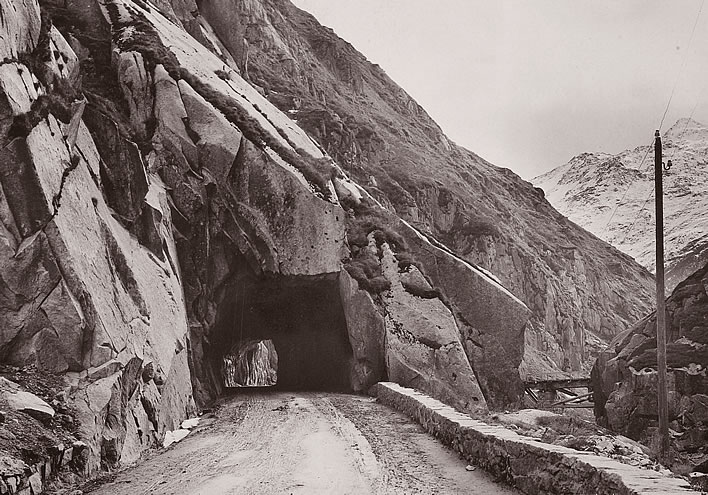

Vue de l'entrée de l'Urnerloch, route du St. Gotthard, c.1841. 'Dessiné par Straub, gravé par Weber', Zürich: H.F. Leuthold. Image: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Alte und Seltene Drucke.

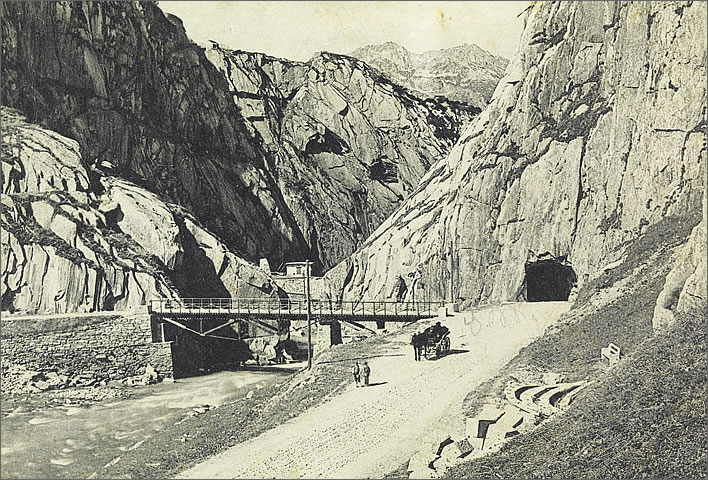

Urnerloch bei Andermatt c.1900. Blick von der Schöllenen nach Süden. The camera confirms that Straub and even Turner produced relatively accurate representations of the north portal of the Urnerloch. Image: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Fotograf: Photoglob AG (Zürich) / Ans_05092-100.

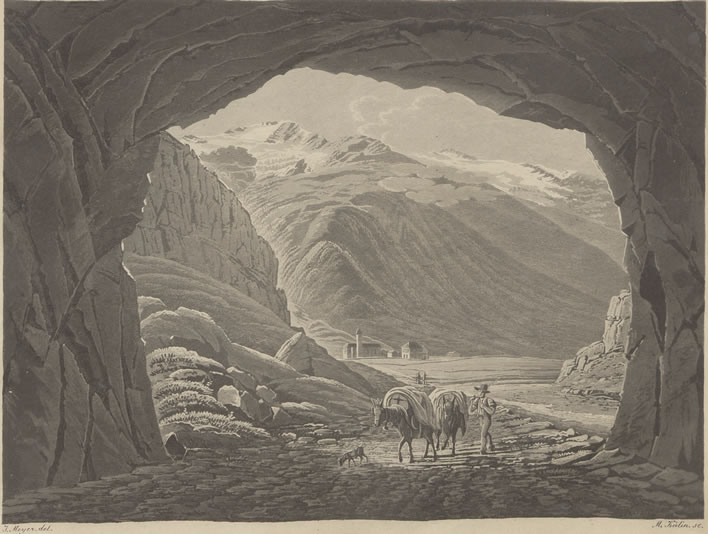

Gallerie dite Trou d'Ury dep. Andermatt, Kälin, M. (del. et sc.), c. 1830. A relatively accurate representation of the view north towards the south portal of the Urnerloch. We are given a good feeling of the descent into the Schöllenen gorge behind the tunnel. Image: M. Kälin; Lusser: Zwölf Ansichten der neuen St. Gotthards-Strasse. Zürich. Heinrich Füessli und Comp., 1830. ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Alte und Seltene Drucke.

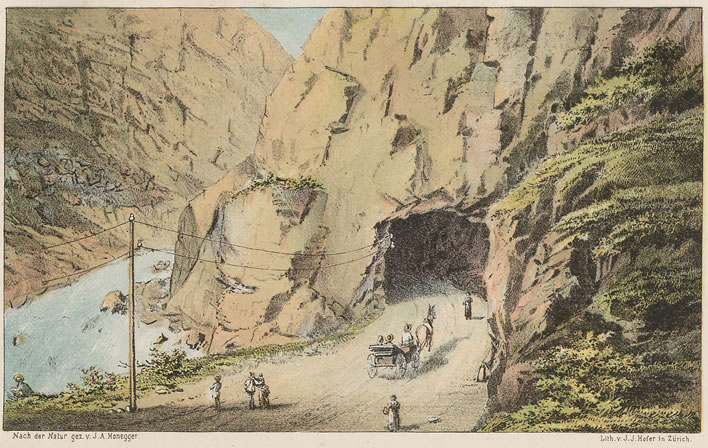

Urnerloch, ND. Image: 'Nach der Natur gez. v. J. A. Honegger, lith. von J. J. Hofer in Zürich' in Der Gotthard: Bahn, Strasse und Tunnel.[S. l.] : [s. n.], [18--]. ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Alte und Seltene Drucke.

The south portal of the Urnerloch in 1910. Image: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Fotograf: Photoglob AG (Zürich) / PK_004847.

Vue depuis la Gallerie d'Urnerloch vers Andermatt, c. 1830. A generously dimensioned tunnel, when compared with the following photograph. Image: Meyer, J. (del.); Kälin, M. (sc.), in M. Kälin; Lusser: Zwölf Ansichten der neuen St. Gotthards-Strasse. Zürich. Heinrich Füessli und Comp., 1830. ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Alte und Seltene Drucke.

The reality of the tunnel in winter. A horse-drawn military sledge convoy enters the iced Urnerlochsometime during the First World War. A good reminder of the hardships of journeys along the Gotthard in winter. In comparison with the previous (and many other artistic works) the tunnel is much narrower in reality. The icicles also remind us how dank the tunnel must have been during other times of the year. Remember that in 1914-1918 this was the standard of road access through the Gotthard, illustrating in turn what a technical advance the rail tunnel from Göschenen to Airolo must have been. Image: Schweizerisches Bundesarchiv - Swiss Archives.

Of the Twärrenbrücke there is now no trace, or if there is, it is under the waters of the dam that feeds the hydroelectric turbines down below in Göschenen. The construction of the railway gallery started the process of obliteration. It is said that hooks and rings could be seen in the rock wall but these are now under water. All that is left is a presumed date of a renovation, 1666, next to a small cross chiselled into the stone.

The new Teufelsbrücke

The Teufelsbrücke lasted another 130 years. Its lowpoint came in 1799 when it became a battleground in the Napoleonic Wars. The great Russian general Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov (1730-1800) fought and won a battle against the French Claude-Jacques Lecourbe (1758–1815) at the Gotthard Hospice on 24 September. In their retreat down the Schöllenen the French filled the Urnerloch with rubble and blew up the Teufelsbrücke. Suvorov hounded the French down, acquired timber, bound together with the lanyards of his officers, to throw across the gap in the Teufelsbrücke. Suvorov's troops attacked wildly over the chasm, finally forcing victory after enduring great losses.

The battle on the Teufelsbrücke between the Russians and the French, 25 September 1799. Image: Etching c. 1800? Artist and source unknown.

The Suvorov monument next to the Teufelsbrücke, 1910. Image: Wehrli, Leo. Suworow-Denkmal in der Schöllenen 1910. ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv /Dia_247-02004.

You see why we called him 'great'. We have not time to list the remarkable feats of his army during that campaign. A monument to him is in the gorge, only a few metres from the modern Teufelsbrücke. Yet despite our admiration for the resourcefulness, daring and bravery of the combatants we note merely that centuries of effort, trade and human progress can be undone in one day of martial glory. The damage to the Gotthard caused great hardship in the region; but then, almost every region in continental Europe suffered in some way during Bonaparte's twenty-year rampage.

The Teufelsbrückewas soon repaired, but had only another 30 years of service ahead of it. Between 1828 and 1830 its successor was erected just behind it.

Carl Blechen (1798-1840), Bau der Teufelsbrücke c. 1830-32. Image: Bayerischen Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, Saal 9. Online.

Pont du Diable (Uri), c.1850. Artist unknown. Image: in Müller, Urs Alfred. 'Alte Landkarten als kulturhistorische Quellen am Beispiel des Passlandes Uri (15.-18. Jahrhundert)', Cartographica Helvetica: Fachzeitschrift für Kartengeschichte, vol 1-2, 1990, Heft 2, p. 2-8. Online.

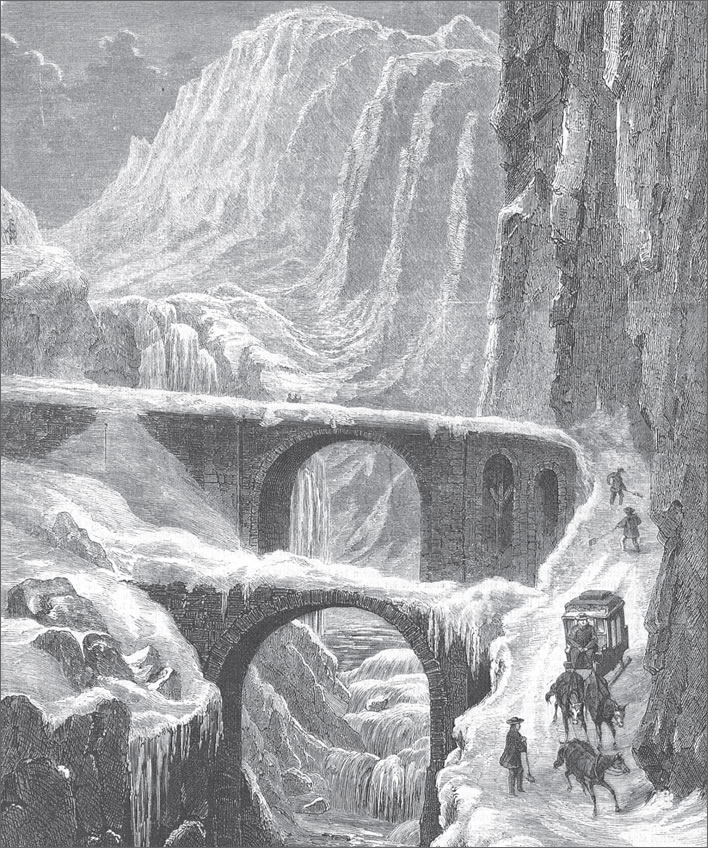

Johann August d'Aujourd'hui (1829-1877), Die Teufelsbrücke auf der St. Gotthardstrasse im Februar d. J., 1863. Are there so few winter scenes set in the Schöllenen because of the endurance required of the artist creating them? The scene here shows conditions that would apply for a large part of the year. Image: Wood engraving (artist unknown) from d'Aujourd'hui's original drawing (now lost), in Weber, Bruno. '"Aber die Kluft ist schauerlich, die sie umgiebt": elf Variationen über die alte Teufelsbrücke der Schöllenen (1595-1888) in druckgraphischen Ansichten von 1707 bis 1863'. Historisches Neujahrsblatt / Historischer Verein Uri, vol 98, 2007. Online.

Ernst Heyn (1841-1894), Die Teufelsbrücke auf der Gotthardstrasse, 1875. Accuracy and mood. Image: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Alte und Seltene Drucke.

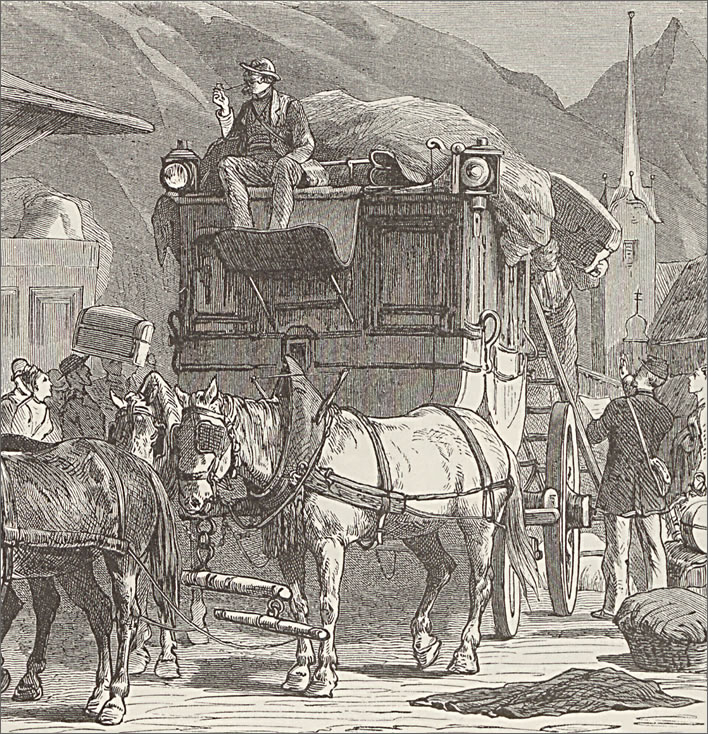

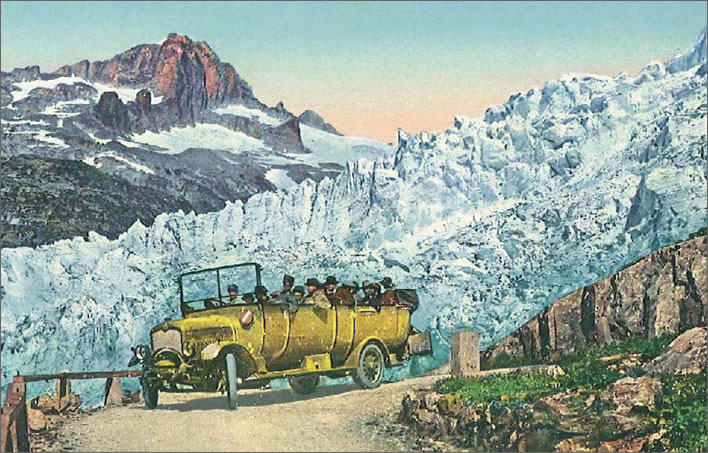

As we would expect, the new bridge was higher, wider and with comforting parapets. It was part of the effort that had begin in 1817 to open up the Gotthard Pass to 'normal' transport: horse-drawn carriages and waggons. A postal service started, carrying passengers and post between Flüelen and Chiasso three times a week. The Gotthard crossing, that used to take several days, now took only several hours. The great era of transport was about to begin.

Rudolf Koller (1828–1905), Die Gotthardpost, 1874. The most famous Gotthard image of all, deservedly so. Image: Schweizerisches Institut für Kunstwissenschaften. Online.

Departure of the post in Flüelen, 1875. Artist unknown. A busy postal centre linking up to the boat services on the Vierwaldstättersee. Image: in Woldemar Kaden: Das Schweizerland : eine Sommerfahrt durch Gebirg und Thal. Stuttgart : Engelhorn, 1875-1877. ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Alte und Seltene Drucke.

Bachmann, Hans (1852-1917), Die Gotthardpost im Winter / Säumerpfad im Winter, 1892. Image: SBB-Archiv.

The old Teufelsbrücke was left standing alongside the new bridge. It lasted until the night of 2/3 August 1888 (i.e. 129 years ago), when 'as a result of continual rain' and already weakened the night before, it collapsed and was 'buried in the lap of the high-foaming Reuss'.

A detail of a postcard from the 1880s. The 1595 bridge is still standing, in front of the 1830 bridge, giving us a good impression of its narrowness and exposure. Image: Postcard published by Emil Goetz in Luzern, Nr. 1226. Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Graphische Sammlung.

Gabler, Arthur (photographer), Pont du Diable, route du St. Gotthard, c. 1880. Image: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Ans_09619.

Gabler, Arthur (photographer), Pont du Diable, route du St. Gotthard, c. 1890. The old bridge collapsed in 1888. Image: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Ans_09702.

If you look carefully at the base of the pillars on the downstream side of its replacement you can just make out the remains of the pillars of that 1595 predecessor.

The remains of the 1595 Teufelsbrücke near the base of the 1830 bridge. Note the characteristic dry-stone construction without mortar, so skilfull that the base is still standing after four centuries of attack by the Reuss.

The Devil had had no hand in the construction of the 1830 bridge, but the tourist name was inherited, even during the 50 years that the first Teufelsbrücke was still standing alongside it.

The railway

The opening up of the Gotthard to normal traffic in the 1830s was a great step when compared with what had gone before, but the high-maintenance route was still extremely vulnerable to weather, rockfalls and avalanches. Twenty years after the opening of the pass road, the railway frenzy finally reached Switzerland and never really ceased: Switzerland has today one of the densest railway networks in the world. The entrepreneurs' eyes looked towards the Gotthard Pass and the possibilities of a railway tunnel safe under the mountain; the idea of the Gotthard rail tunnel was born.

Alfred Escher (1819-1882) was the Swiss politician and banker who oversaw the project, Louis Favre (1826-1879) the Swiss engineer and entrepreneur whose company carried out the work. Tunneling started in the autumn of 1872. The technical daring of the project, particularly the quite brilliant feats of surveying, is a commonplace. However, seen with the cool head of hindsight the project was a financial and managerial catastrophe. Had the sponsors known how difficult, expensive and overdue the project would be, it is difficult to imagine that it would ever have been started.

The railway tunnel project was forced forwards towards impossible deadlines. The German expression describing this procedure is 'auf Teufel komm raus', 'until the Devil comes out'. English speakers say less hysterically 'come what may' or 'at any price'. The Devil of the Gotthard certainly had his moments during the construction of that railway. In the Schöllenen the railway bridge across the gorge stands a few metres upstream from the 1830 Teufelsbrücke and the line runs alongside the Urnerloch in a gallery.

Much worse, the project was not only a financial and management shambles, it was also an industrial tragedy. Of the mainly Italian workforce many hundreds died or had their life expectancy shortened. The official death toll is 199, a ridiculously low number because any worker who was injured or ill or in the process of dying was immediately shipped back home to die a death that was never counted. Long term effects such as silicosis were never documented.

The army of the damned

The working conditions were indescribably bad – heat (c. 40+°C), noise, the air thick with rock dust and toxic gases from the explosives. The workers' accommodation was appalling and their pay miserable (with many deductions). In the brutal suppression of a strike in July 1875 four Italian workers were shot and killed and several others badly injured. The risks and conditions inside the tunnel may have been unavoidable for the time, but the pay and terrible conditions of the slave labourers are beyond comprehension for modern minds.

The Swiss authorities played a dishonourable role in aiding and abetting the exploitation of the slaves and suppressing information about the true state of the workforce. It took fifty years after the opening of the tunnel before these unfortunates got the cold comfort of a memorial, many years after their taskmasters' statues had been erected in prominent positions by a grateful nation.

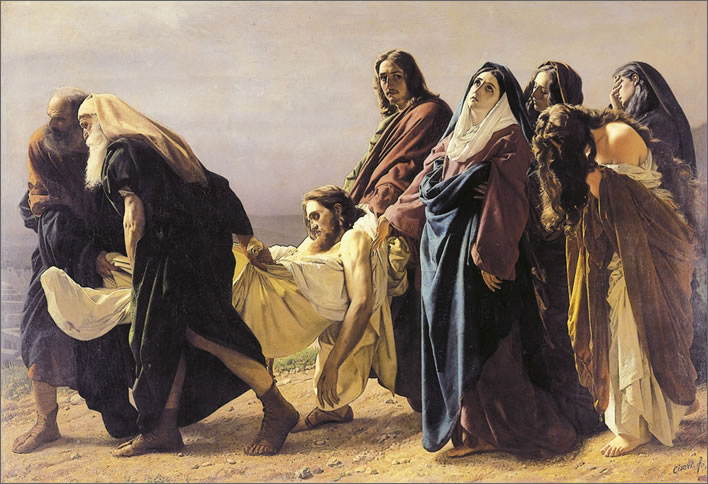

Even this gesture, the bronze relief Vittime del lavoro, was initially paid for entirely by the sculptor, Vincenzo Vela (1820–1891), a principled and patriotic man, when he created it in 1882. 'In these times when millions are spent on memorials to the rich', he wrote, 'it seemed to me to be necessary to remember the martyrs of labour'.

The motive in the relief is of a dead worker being carried off on a stretcher, alluding to a similar scene by another Tessiner artist, Antonio Ciseri (1821-1891), Il trasporto di Cristo al sepolcro, 'Bearing Christ to the Sepulchre' (1864-1868). In Vela's relief, not only is the dead worker the symbolic Christ, his face is Vela's self-portrait.

Vincenzo Vela's plaster model of Vittime del lavoro, 1882. Image: Museo Vela.

Antonio Ciseri, Transporto di Cristo al sepolcro, 1864-1870, thought to have served as the inspiration for Vela's Vittime. Image: Il Sacro Monte di Orselina, La Madonna del Sasso.

Creating the relief was one thing, erecting it quite another. The plaster model was exhibited at the Swiss National Exhibition in Zürich in 1883, pointedly for those with eyes to see behind a bust of Favre. In 1893, two years after Vela's death, the plaster was cast in bronze at the request of the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna in Rome and kept in their collection.

The great and the good had their monuments in busy central locations – no one more central than Alfred Escher, a massive statue which now stands on a traffic-rich intersection at the side of the main station in Zurich, gazing down the Bahnhofstrasse past the bank now called Credit Suisse, which he founded, to the Alps beyond.

Splendid isolation, not to be overlooked: Alfred Escher's statue in the Bahnhofplatz in 1893. The main railway station is on the right of the picture. Image: Baugeschichtliches Archiv, Amt für Städtebau, Stadt Zürich.

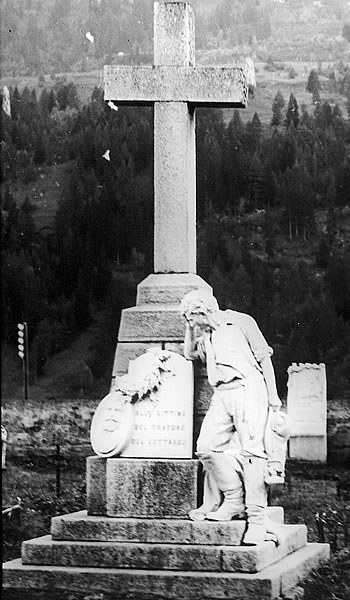

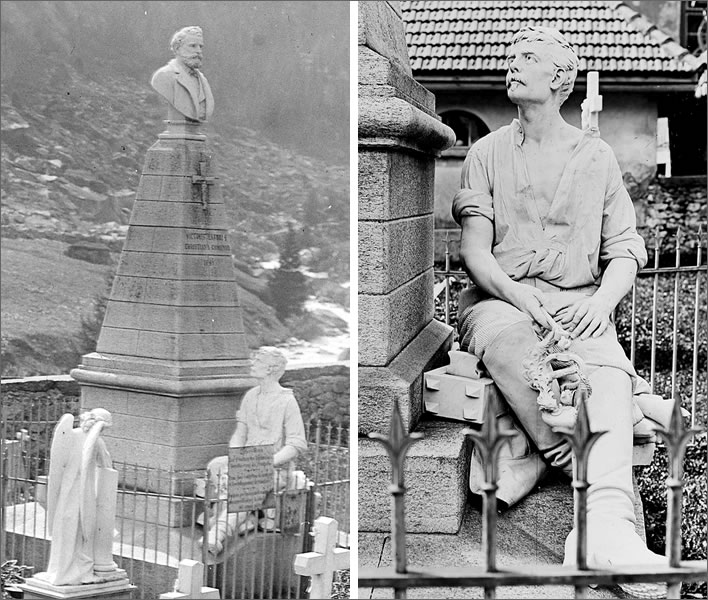

Money was collected for memorials in Airolo and Göschenen. They were erected in the town cemeteries where hardly any stranger goes. Both memorials were executed by Pietro Andreoletti (1841-1932) and put up around 1889. In Airolo, the figure of the worker gazes up full of wonder and gratitude at the bust of Louis Favre, the image of his persecutor. In Göschenen, the worker gazes down sorrowingly at Favre's image on the relief plaque. Both monuments are entirely centred around Favre, so much so that some have been misled into thinking that one or the other monument marks his grave. These memorials are a travesty, both in their location and their iconography, but especially outrageous in that they were partly financed by the pennies of those workers who contributed.

Andreoletti's Gotthard monument in the cemetery in Airolo. Image: Wehrli, Leo (photgrapher), 1933, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv.

Andreoletti's Gotthard monument in the cemetery in Göschenen. Image left: Favre-Denkmal (Übersicht), Göschenen, 1910, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich,Bildarchiv. Image right: "Favre-Denkmal (Detail), Göschenen, 1910, ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv.

In contrast, Vela's Vittime del lavoro is a moving and honest memorial –which may be the reason that, apart from its first outing at the National Exhibition in 1883, it spent 50 years being visible on to visitors to an art gallery in Rome. It was only erected in 1932 at Airolo station to mark the 50th anniversary of the completion of the tunnel. The Swiss Federal Railways embedded it in an unimaginative block on the edge of the carpark of Airolo railway station, behind the cars and the buses.

Vincenzo Vela's bronze Vittime del lavoro, erected facing the carpark in Airolo railway station. Image: ©Peter Walter, 09.06.2007.

Locating this monument in Airolo was in itself an outrage: the memorial, supposedly intended as a focus of remembrance, commemoration and gratitude, is positioned safely in Airolo on the southern, Italian-speaking side of those mountains whence the victims came, whereas the remembrance, commemoration and gratitude should really be felt on the northern, German-speaking side of those mountains – but let us not trouble their business-like minds with such dark thoughts.

The age of steam and electricity

The Urseren who made the first breakthrough in the Schöllenen had their minds focused on their own interests. They knew why they were doing what they did, even if they didn't realise the transformation they would cause. That first route benefitted the valley of the Reuss and brought unforeseen benefits to Switzerland as a whole. Making the Gotthard Pass accessible to normal traffic in the 1830s also brought additional benefits to the locality and to Switzerland.

Muheim, Jost (1837-1919), Bahnhof von Göschenen, 1891. Steam trains entering and leaving the new railway tunnel. Image: SBB-Archiv.

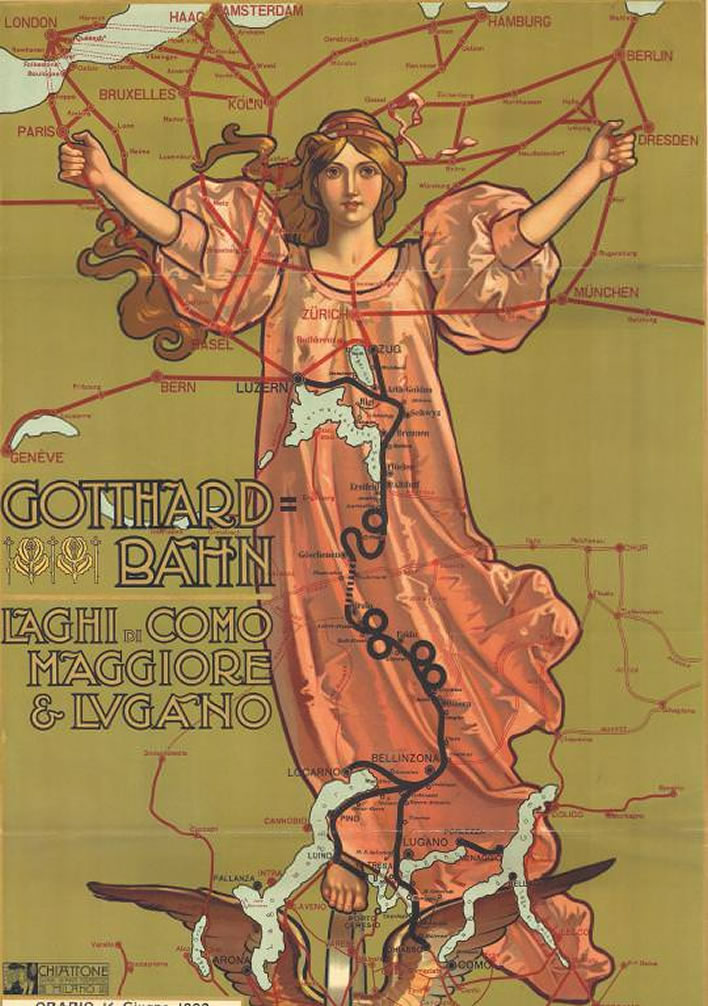

The poster Gotthard-Bahn – Laghi di Como, Maggiore e Lugano, contains the timetable 'Orario 16. Giugno 1902'. Created by G. Chiattone, Milano, 1902. They just don't do railway timetables like they used to. The poster also demonstrates the European dimensions of the Gotthard rail project: all the twirls and the little dotted line between them were there for the Germans, the French and the Italians. Image: SBB Historic.

In contrast, the railway tunnel was very different: this was not a tunnel for Switzerland but for Germany and Italy. After the near collapse of the project it was Germany and Italy who picked up the bill, in the end paying four-fifths of the total cost, which they did because of the immense advantage the Gotthard railway tunnel was to them. As far as Switzerland was concerned, it took the passing trade away from the people who had benefitted from it for the eight centuries since 1200.

In the 18th century, the Schöllenen and the legend of its Devil's Bridge had inspired Goethe to place a pact with the Devil at the centre of his drama Faust. The railway tunnel was also a pact with the Devil by the Swiss. During the Second World War a Swiss politician suggested that Switzerland should blow up the tunnel, since it worked to the great benefit of the Axis powers. The only advantage of the rail tunnel for Switzerland was the political one of bringing the Tessin to the south of the Alps closer to the north of Switzerland.

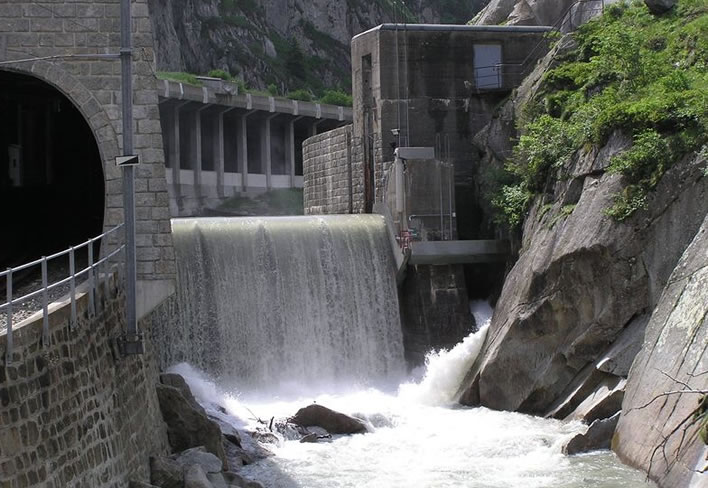

The tunnel was opened to traffic in May 1882, almost ten years after it had been started. For around the first 40 years of its existence the it was used by steam locomotives, creating a ventilation nightmare that, in the haste to build the tunnel, was somehow never fully anticipated. In 1899, nearly two decades later, a ventilation system was finally installed, a Heath-Robinson effort driven by a spare locomotive in a shed next to the north portal. After that in 1902 the waterpower of the Reuss in Göschenen was used.

Only after the autumn of 1920 were electric locomotives used. That moment marks the point when the immature technologies of railways and tunnels came of age. In its maturity it was very successful. By the 1950s the Gotthard route was effectively subsidising the rest of the Swiss Federal Railways.

The age of the motor vehicle

The technological maturity of rail was overtaken after fifty years by the maturing technology of road transport. By the 1950s the developed countries of the world were seized by a road-building frenzy. Road transport in many respects is technologically more advanced than rail, that's why it is so popular. When the roads exist the journey can start when and where required and end when and where required; no luggage needs to be trollied about; no disrupting changes of train are required and no strangers eating stinking snacks need be tolerated.

Like everyone else in Europe, Switzerland also broke out in a road transport frenzy. Starting in the 1950s plans were drawn up to plaster Switzerland in asphalt, also on the basis of auf Teufel komm raus–which he frequently did. Three major transit motorways were to be joined up in the middle of the historic old town of Zurich, for example, a plan that lasted a surprisingly long time before it was scrapped.

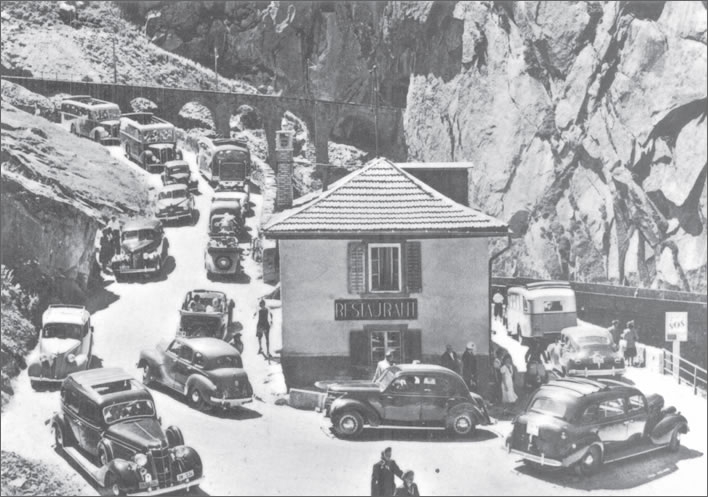

The changes that ten years of road transport bring.

Top: Postcard, 1952 – Traffic in the Schöllenen, Teufelsbrücke.

Bottom: Traffic on the Gotthard Pass, 1962. Image: Metzger, Jack (photographer), ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Com_C11-202-02.

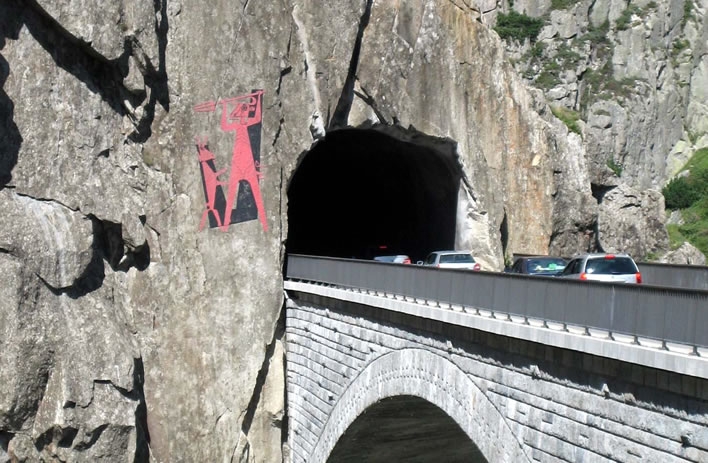

In 1953, concrete was king on the Gotthard route. A new route through the Schöllenen was built: a new Teufelsbrücke sprang across the Schöllenen gorge high above its predecessor. It was branded with a devil-graphic on the rock wall, lest his instruments forget the creature who has been their most constant companion on this route. The road sweeps on through a gallery to the much extended Urnerloch. The Tessiner side of the route, the Tremola, was substantially rebuilt. The reconstruction project was finally finished almost exactly thirty years later. Ever since, more and more concrete has been poured on various bits of the route, even until quite recently.

The 1832 and the 1953 Teufelsbrücken in 2004. Image: ©Roland Zumbuehl 2004

The Devil's branding on the 1953 Teufelsbrücke by the Urner artist Heinrich Danioth (1896-1953) taken in 2007. Image: ©Adrian Michael.

The myth of Swiss political rationality still lingers on in some minds, but it really is a myth. In May 1970, after a dozen years of pouring concrete on the Gotthard Pass route, construction began on a road tunnel through the mountain, connecting Göschenen in Canton Uri with Airolo in Canton Tessin. The project took ten years, just like the railway tunnel, and the road tunnel was opened in September 1980. Large feeder motorways bring the traffic of Europe to its portal. The drive through the road tunnel is an unpleasant experience: the tunnel is a single 17 km tube with a contraflow system. A safety and rescue tunnel was only added into the design just before the start of the project.

Top: Aerial view of Göschenen in 1963. Image: 'Schöllenen (N2) 1963'. Image: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Fotograf: Comet Photo AG (Zürich) / Com_F63-00891.

Bottom: Aerial view of Göschenen in 2007, after 44 years of concrete pouring to improve the old route and create the road tunnel etc. etc. Image: ©Schweizer Luftwaffe, 2007

As with the first rail tunnel, the main beneficiaries of the road tunnel were Germany and Italy, plus, of course, poor old Tessin, traditionally isolated from the rich north. At a stroke this tunnel made the existence of the pass road senseless, but in the political schizophrenia of the time the pass route would nevertheless go on being extended for thirty years or more.

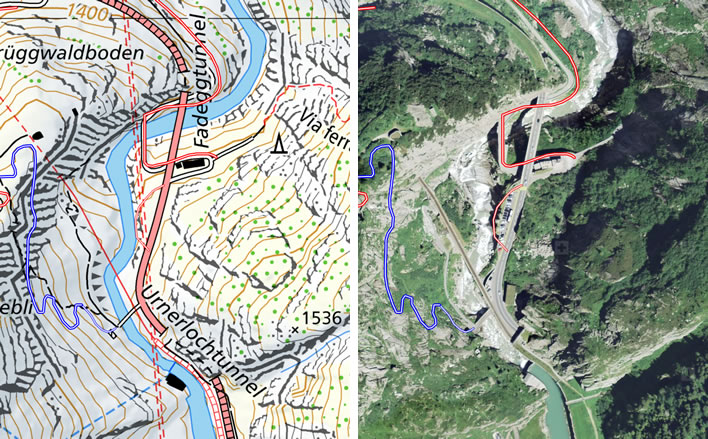

Some modern cartographic detail for the upper Schöllenen with the Teufelsbrücke and the Urnerloch. The thick red line is the modern road that was built in 1953, the very thin red line the railway of 1882, the medium-thickness red lines are footpaths of national importance, which correspond largely with the route of the old road before 1953. The photograph from 1952 shows the traffic above the Teufelsbrücke in the loop of road around the restaurant. A path leads off from the bend of the loop to the Suvorov monument, then a few metres further to the start of the Via ferrata de diavolo, the route for adrenalin junkies up the side of the mountain. The blue lines are footpaths of local importance (military roads, farm tracks etc.). The reservoir for the hydroelectric power station can be clearly seen alongside the Urnerloch tunnel in the aerial photograph. Images: ©Data: swisstopo, FEDRO, FEDRO + canton. Online.

Displacement thinking

Towards the end of the 1980s the Swiss had another think about transport. The convenience of driving people and goods from Hamburg through the Gotthard to Italy had been bought at the cost of filling the pass itself with huge concrete structures as well as along all routes between. Even taking into account the unpleasant transit drive, the artificially throttled back traffic through the tunnel and the huge traffic jams before the entrances (as this is written the current tailback is nearly 20 km on the northern side), the Gotthard Pass is still a magnet pulling many of the tin boxes of Europe towards it. The Devil certainly knew this, if no one else did: traffic increases to fill the capacity available.

That 'other think' produced a strange decision, the Verlagerungspolitik, 'displacement policy'. All this traffic had to be pushed onto rail transport – in effect, a technological step back – and everything must be done to discourage road transport, whether private or commercial. If that meant four hour traffic jams, so be it. If that meant a huge increase in the demand for electrical energy that had previously met by tanks of fuel, so be it. It seems that all the concrete that had been poured and which would continue to be poured for some time was poured in vain.

There will be Swiss, now they have reached prosperity and have decided to save the planet, who probably wish that the Walser had left the Schöllenen impassable.

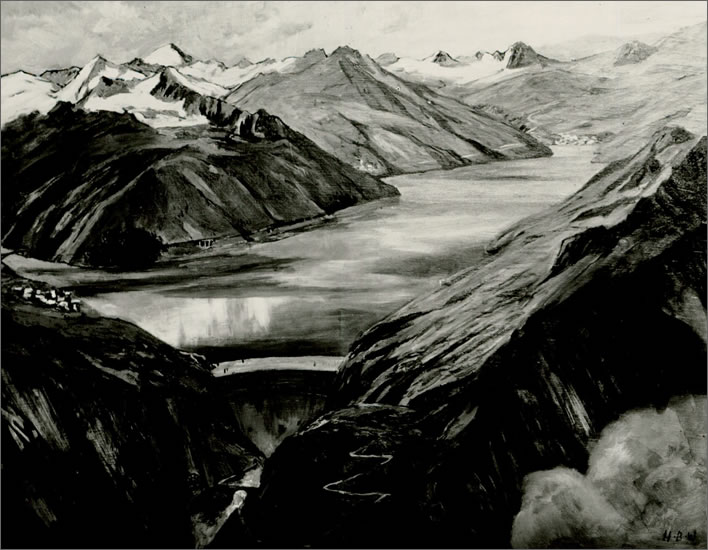

The rail line from the 1880s with its loops and curves could not cope with the displacement policy. The Swiss came up with a project for a direct rail tunnel between Erstfeld (not far from Flüelen) and Bodio, near Biasca, a tunnel that would be almost level and run for most of the time almost in a straight line. It would be 57 km long, with two tubes. The desire was that trucks would be loaded onto trains, preferably before they even entered Switzerland, then unloaded, also preferably outside Switzerland.

The Swiss have just completed this railway tunnel. The question of why and for whom it was built is now, after its completion, a matter of debate. Unlike the first rail tunnel and the road tunnel, Germany and Italy seem indifferent to the new tunnel's charms. Their commitment to building suitable connecting lines in Germany and Italy has evaporated. The European Union is now an east-west organization, not a north-south one. No one in either country shares Switzerland's enthusiasm for pushing road traffic onto rail.

Things have now got so bad that little Switzerland is having to cajole the Germans into building their promised railway links and is even paying Italy to build the connections on its side of the border.

Tunnels in their nature are a bottleneck –they have to take both slow goods trains and fast passenger trains, a permanent conflict for the tunnel railway. The laws of physics prevail: the capacity of the tunnel increases as speed reduces. If the new tunnel is successful and its traffic massively increases its capacity will be quickly reached. Tunnels have so many disadvantages that they are things you build only when you have no other option.

The Schöllenen road route is now being enhanced for the use of 'slow traffic', that is, walkers and bikers. They are being separated from the motorised traffic. The concrete brutalism of the structures from the 1980s is being softened by stone cladding.

Walking fun in paradise, alongside the road under the gallery, 2003. Image: wandersite.ch.

There is no doubt that motorised traffic over the old pass road will be severely restricted, just in case some Dutch family stuck in the queue to the tunnel decides to break free and choose the interesting, fresh-air route.

Unlike all the other engineering developments since the railway in the 1880s, the villages of the Reuss valley may at long last get some tourist benefit from their pass. For visitors who miss the excitement of the 1595 Teufelsbrücke and even its 1830 successor, there is now a route of metal staples driven in the cliff next to the Suvorov memorial that can give them all the pointlessly frightful exposure they could wish for.