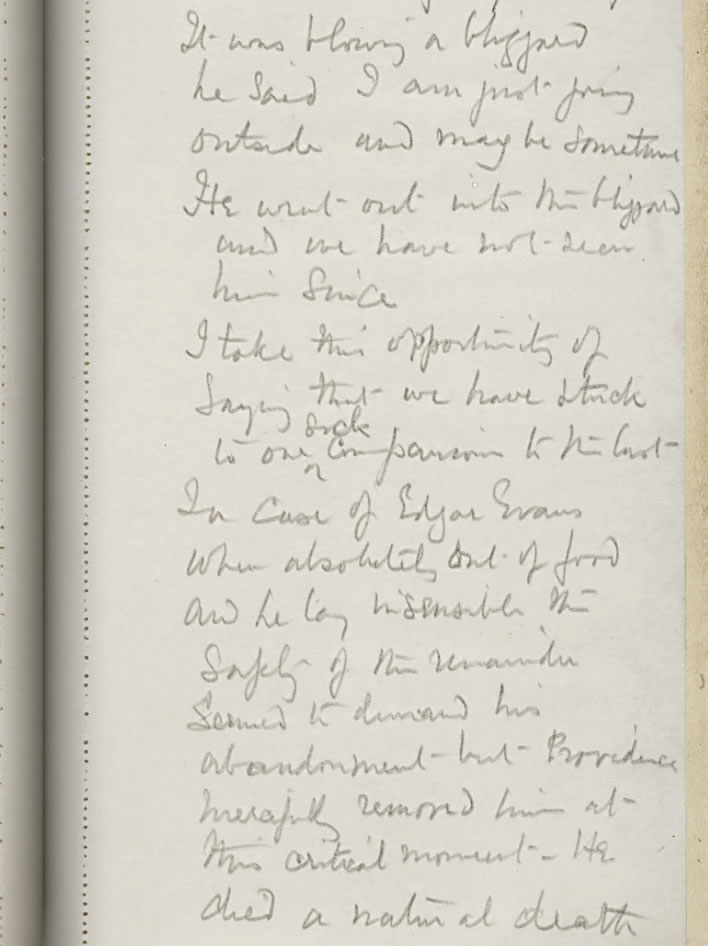

An outrageous libel of a dead hero 2

Richard Law, UTC 2017-11-05 12:16

Introduction

Readers might want to lay down supply depots and plan overnight camps before embarking on this journey – it will be a long haul. Some may not come through, having decided that a short stumble into an icy blizzard would be a quicker way to go and certainly much more fun.

Some years ago Professor Chris 'Ship of Fools' Turney got it into his head that Lieutenant Edward 'Teddy' Evans, second-in-command on Captain Robert Scott's disastrous Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole in 1911/12 had consumed more than his fair share of rations from the depots on his return journey to base camp, leaving Scott's polar team, that was following about a month behind him, short of food. This contributed to the demise of Scott's team, which was only eleven miles away from a substantial supply depot.

Here is Turney's summary from the conclusion of the abstract of his latest paper on the subject:

It is concluded that Evans actions on and off the ice can at best be described as ineffectual, at worst deliberate sabotage. Why Evans was not questioned more about these events on his return to England remains unknown.

Turney 498

The very model of a modern academical, Turney milks this theme to get as many papers in as many journals as he can and leverage the power of the press release to disseminate his name and his ideas as widely as possible. We reviewed one of the press reports last month, but the following is a critical examination of Turney's paper that was the source of these smears.

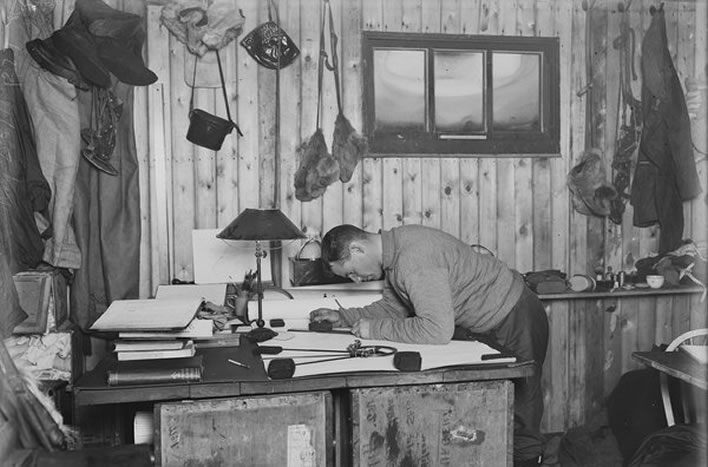

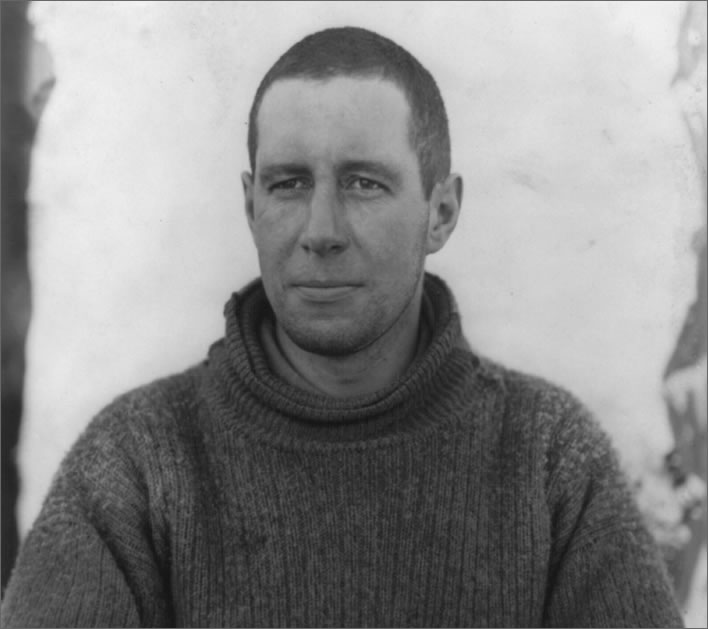

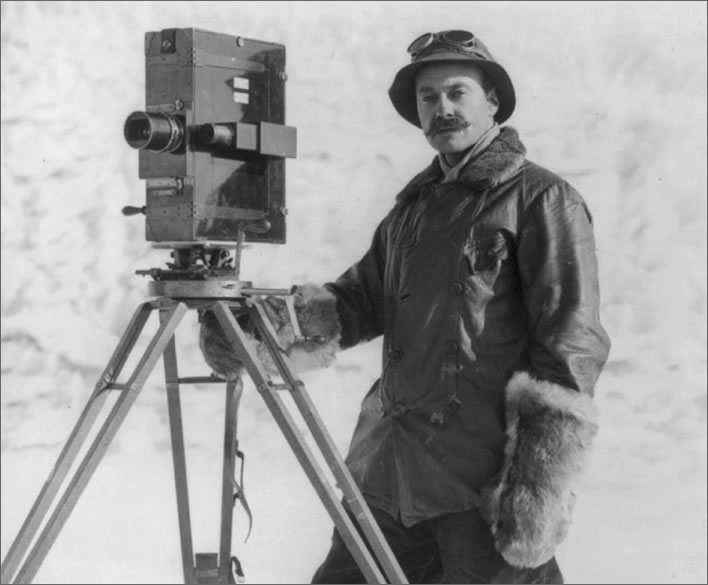

Teddy Evans working on a map in the hut at Cape Evans. May 1911. Image: Photographer Herbert Ponting. British Antarctic Expedition 1910-13 (Ponting Collection), P2005/5/1375.

In order to support this argument Turney attacks Evans and his reputation in a number of ways. The attack is with a scattergun, not a rifle, making refutation of his smears – for that is all they are – extremely tedious. The smears are packaged up into little parcels tied up with odd syntax, making the task of refutation even more complex. Worst of all for us, however, Turney is a skilled smearer who can pack three different smears into one or two sentences.

The disentangling of these smears and the satisfactory rebuttal of them demands much labour, which is why we have to warn the reader of the long haul ahead. But Turney will keep generating papers and press releases out of these smears for as long as he can, so the job has to be done.

Since Turney packs his smears in mixed bundles, we have to unpack them in order to deal with them systematically. Here is a list of Turney's main smears, which we shall take in sequence.

- Evans blocked the appointment of the mechanic Reginald Skelton to the expedition, the man who was most able to work with the expedition's motorised sledges.

- As a mechanic, Skelton was far superior to his replacement Bernard Day. Unlike Day, Skelton would have made a success of the motorised sledges.

- Evans, who was in charge of the motorised sledges, was publicly critical of the them: his heart wasn't in their use.

- On his team's return journey north, Evans ate more than his fair share of the rations stocked in the depots.

- Evans failed to pass on Scott's last instruction about the dispatch of a dog team to meet his party.

- Evans was afflicted by snowblindness and scurvy on the return journey. That he developed scurvy was his own fault. As a result of the scurvy he ate even more than his fair share of rations and tried to obfuscate the date of the onset of the scurvy to give him a justification for eating the rations of Scott's team.

- Evans was a useless slacker who could not be trusted. Evans hated Scott because Scott left him off the party going to the South Pole. Eating Scott's rations was a revenge for this slight.

- Evans' misdeeds were covered up by the powers that be. Evans was not interrogated properly.

These are the major points from nine pages of text in Turney's latest paper on this theme. Just glancing at this list, the reader will appreciate what we are up against in dealing systematically with Turney's assertions against Evans. There is nothing for it but to lower our heads and trudge out into the blizzard of detail – we 'may be some time'.

Map overview

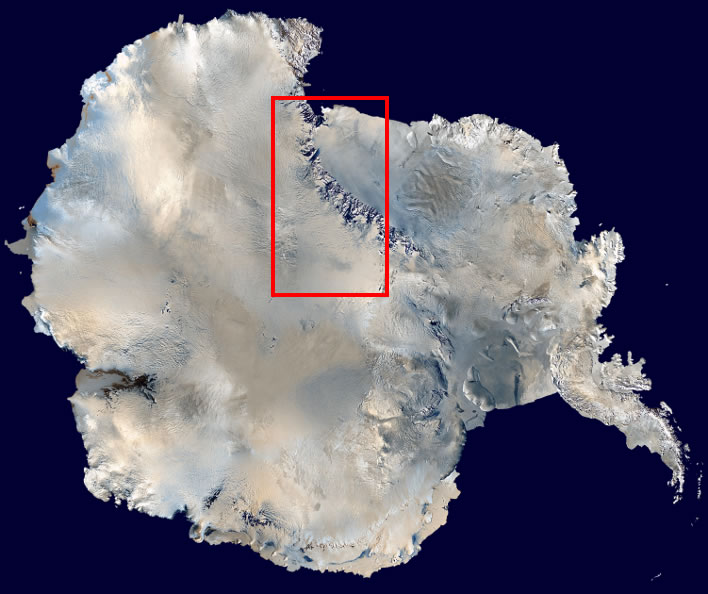

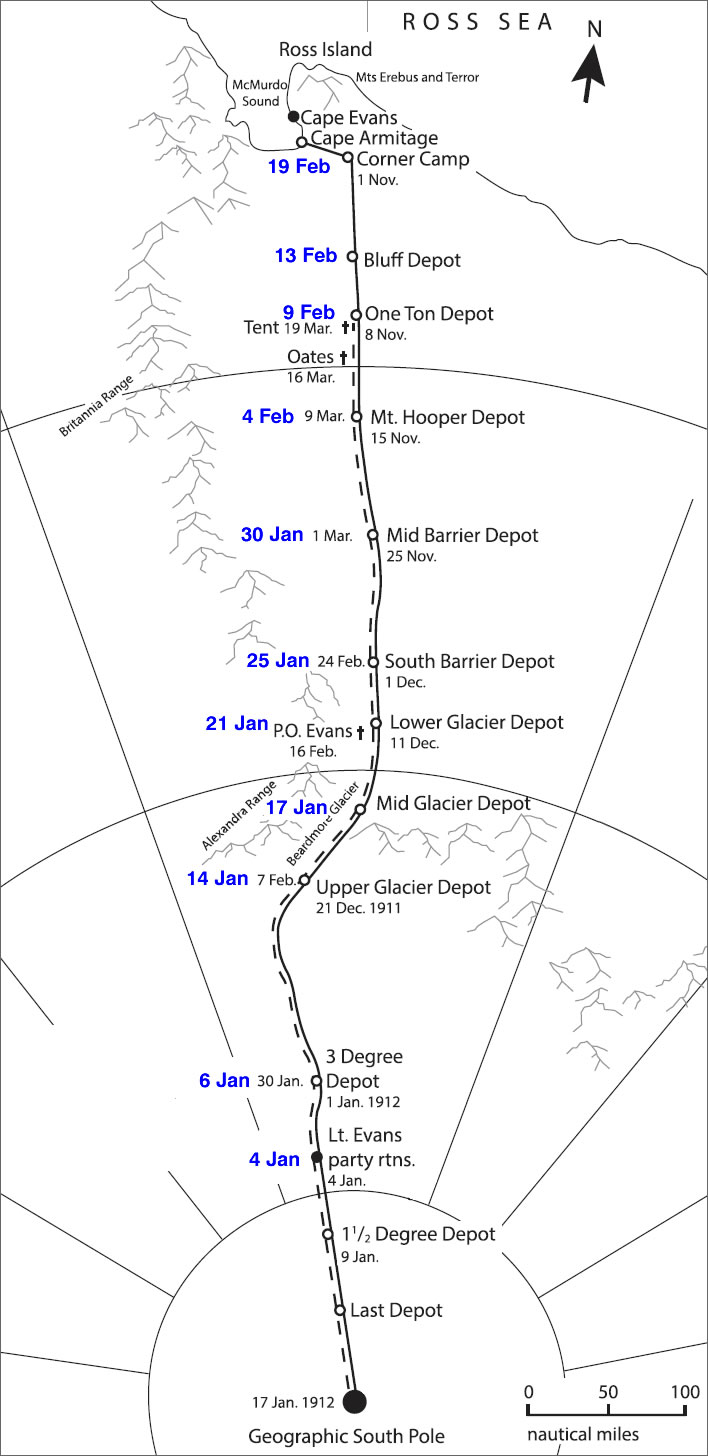

Antarctica. The red rectangle is the approximate area shown in the detail map below. Image: NASA.

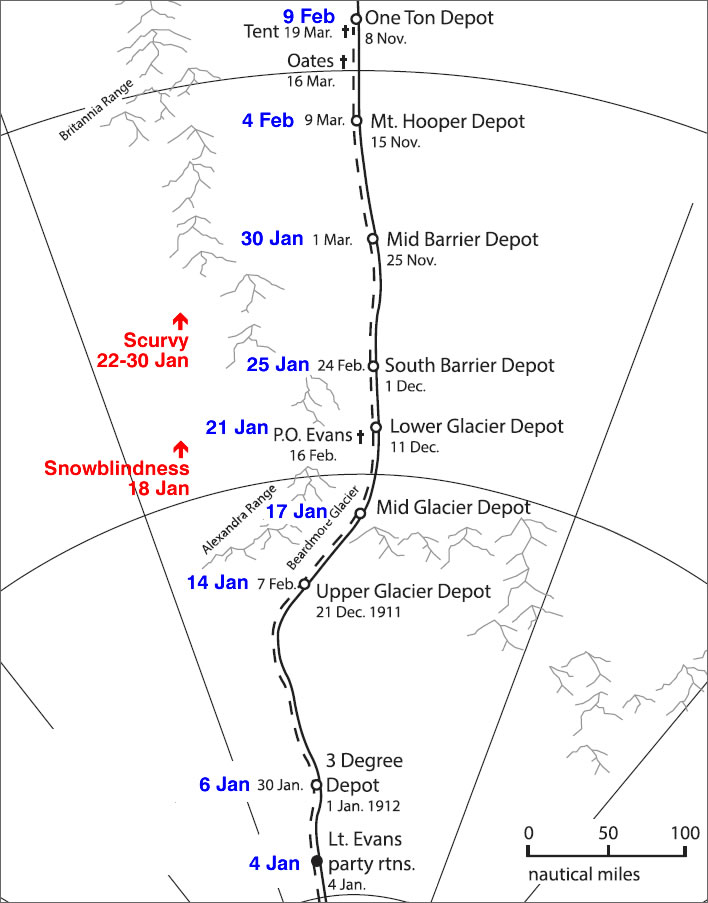

Scott's expedition route to the South Pole and the return routes of the various parties.

—The solid black line is the route from base camp to the South Pole with the dates of arrival at the depots on the outward journey.

—The dashed black line is the route of the Polar Party from the South Pole to their death tent.

—The dates of the arrival of the Polar Party at the depots are shown in black.

—The dates in blue are the dates of the presence at the depots of Evans' team, the Second Support Party.

Adapted from [Turney 499]

Motorised sledges

Turney wants us to believe that Evans' antipathy to the use of motorised sledges and his opposition to Scott's nomination for the mechanic on the team were contributory factors in Scott's failure. What this has got to do with stolen rations is anybody's guess, but it is one more allegation with which to smear Teddy Evans. Turney describes Scott's faith in motorised sledges as follows:

To ensure success, Scott proposed using motorised sledges for hauling supplies and equipment across the Ross Ice Shelf to relieve the workload on the horses, dogs and men.

Turney 500

That's an odd way to put it. Relying on motorised sledges was no way to 'ensure success', just the opposite – Scott was relying on an extremely immature technology that he hoped would be kept going by the presence of Reginald Skelton, a naval engineering officer known to Scott, who had been tinkering with motorised sledges for a couple of years.

Using only Skelton's account of the affair, Turney blames Evans for keeping Skelton out of the expedition, implying that his absence was responsible for the failure of the motorised sledges.

With sufficient spares and the experienced Skelton, how much further might the motorised sledges have taken supplies? Historian Roland Huntford has suggested 'fifty or hundred miles … is not insignificant' (Huntford, 2009), a distance that would have made all the difference a few months later. In spite of his opposition to Skelton's participation and the problems that ensued on the ice, Evans was publicly critical of the sledges on his return from Antarctica:

…[A] week after Lashly and I had first set out as the pioneers with those wretched failures, the motor sledges… (Evans, 1921).

Unfortunately, Evans' insistence that Skelton be removed from the expedition almost guaranteed such a result.

Turney 502

Where do we begin in untangling this jumble of half-baked speculations? In reading Turney's piece the reader has to be constantly on the alert for such contorted passages that weave several smears about Evans together in one brief section of text.

Take, for example, the incomprehensible 'publicly critical of the sledges' in spite of 'his opposition to Skelton's participation', a good specimen of Turney's impressionistic smearing. It generates an odour of incompetence and hypocrisy about Evans, but what does it mean?

Then we are given Huntford's suggestion that an extra 50 or 100 miles of motorised sledge transport would have been useful. Possibly, possibly not. But in the real world the sledges didn't perform well and finally broke down completely – in the end they were more of a hindrance than a help. Evans' team achieved the same result by manhauling the supply sledges.

Turney then slips in the nonsensical assertion that those extra miles 'would have made all the difference' on the return journey, to which we can only repeat ourselves: Evans' team achieved the same result by manhauling: their heroic efforts ensured that the provisioning goal was achieved completely and within schedule.

Freeing ourselves from the contorted syntax, we see that there are two major smears in this instance, which we have to deal with individually: 1) the impact of the absence of Skelton and 2) Evans' critical attitude to Scott's sledges – namely, that if only the sledges had worked better and gone further the expedition would have been a success and no one need have died. Readers will need some patience while we sort this mess out.

Skelton the genius, Day the incompetent?

Turney writes:

Scott was forced to remove Skelton from the expedition, with the inevitable loss of technical support for the motorised sledges

Turney 501

We cannot blame Evans for the removal of Skelton. If Scott had insisted on having Skelton he could have kept him. Scott was never 'forced to do' anything, let alone by the person he himself had appointed as his second-in-command, yet Turney keeps repeating the 'forced' mantra:

With the forced loss of Skelton, Scott had reached out and recruited Bernard Day, motor specialist on Shackleton's Antarctic Nimrod expedition when the Anglo-Irishman had taken the first motor vehicle south. But the improvised engineering experience does not appear to have been sufficient.

Turney 501

In fact, Day was a highly experienced motor mechanic and engineer, who had worked for a motor manufacturer and had extensive Antarctic experience. His appointment to the expedition can hardly be called 'improvised engineering experience'. It is ridiculous of Turney to attribute the many breakdowns of the motor tractors to Day's 'improvised engineering experience'. This latter phrase is yet another of Turney's impressionistic smears, since it could apply to the appointment of Day or to his skills.

If Turney wants to make a case that Skelton would have been a superior mechanic to Day, he needs to bring more evidence to the debate – asserting that his 'engineering experience does not appear to have been sufficient' is just a speculation based on no evidence at all.

In fact, of course, he cannot, because we have no way of knowing how Skelton would have done in the conditions that Day faced. We can be sure, though, that the mere presence of Skelton in the team would not have prevented the critical mechanical failures that ultimately doomed the use of the motors. The appointment of Day meant that there was never 'the inevitable loss of technical support for the motorised sledges'. It's an easy smear.

Day was in a difficult position: he was the one most open to blame when things went wrong:

By 24 October, 'the motors seemed ready to start and we all went out on the floe to give them a "send off". But the inevitable little defects cropped up, and the machines only got as far as the Cape. A change made by Day in the exhaust arrangements had neglected the heating jackets of the carburettors; one float valve was bent and one clutch troublesome' (R. F. Scott, 1913a).

Turney 501

Far from losing Skelton's magic with motor sledges, in Day the team now contained a specialist motor engineer who performed wonders with the delicate mechanisms in his care. Day had been Shackleton's engineering specialist and had plenty of experience with engines in cold conditions. Skelton's supposed superior magic could not have prevented cracked big ends, wrecked bearings and ruined pistons – many metals become brittle at the low temperatures in the Antarctic.

Repairs were carried out with the spare parts the team had, but they took time. A mechanic in a warm workshop might replace a piston rod in a few hours. On one occasion it took Day and Lashly, in the open at around -20°C, protected only by a makeshift canvas, from around 3 p.m. to 11 p.m. – eight hours – to replace the bearing in a big-end.

With sufficient spares and the experienced Skelton, how much further might the motorised sledges have taken supplies?

Turney 502

Repairs were never inhibited by shortage of spares. Even if there had been more spares, where was the additional motorised sledge that would be needed to carry them?

Scott's (and Turney's) shaky grasp of technological matters is revealed in a remark quoted by Turney:

Two days later the remaining machine failed, 'The big end of No. 1 cylinder had cracked, the machine otherwise in good order' (R. F. Scott, 1913a).

Turney 502

The technologist would say that with a cracked big end, the rest of the machine was merely scrap metal. Scott is here using the old 'Curate's Egg' argument in trying to find something good to say about this obvious failure: 'parts of it are excellent, my Lord'. The motor tractor was useless, but everything on it bar a single big end was working well.

The greatest problem Turney has with his elevation of Skelton and his denigration of Day is that it was Skelton, after all, who designed the motor tractors. If there is any blame to be apportioned for their inadequacies then it should be directed at Skelton, not poor Day, who could only try and do his best with what he had been given. In a moment of doubt, even Scott recognises his debt to Day as the latter copes with a design fault in the motors:

It is already evident that had the rollers been metal cased and the runners metal covered, they would now be as good as new. I cannot think why we had not the sense to have this done. As things are I am satisfied we have the right men to deal with the difficulties of the situation.

Scott 27 October 1911

Evans the luddite

In Turney's mind this late learning of Scott's about the usefulness of motorised sledges is twisted into being another fault of Evans':

On the ice, Scott's concerns over Lt. Evans' abilities intensified, possibly made worse by increasing problems with the motor sledges.

Turney 501

Another incomprehensible conjunction: how could any rational observer associate 'Evans' abilities' with the 'increasing problems with the motor sledges'? Is he suggesting that Evans' very presence in the party caused bearings to disintegrate and connecting rods to crack?

As we have already noted: Scott's rash use of such an immature technology was not the fault of Evans. As far as the lack of Skelton's magical presence is concerned, Scott could have easily overruled Evans' objections had he wanted to. Turney is attributing to Evans much more say in the expedition than he really had. The decision to exclude Skelton was Scott's. The decision to rely on motorised sledges was Scott's.

Evans and his team made the best of a bad job – even Turney cannot suggest that the efforts of Evans' team to make up for the failure of the motorised sledges were anything but heroic. However, if Turney knows this, he keeps quiet about it, being too bent on slandering Evans:

Evans was publicly critical of the sledges on his return from Antarctica:

…[A] week after Lashly and I had first set out as the pioneers with those wretched failures, the motor sledges… (Evans, 1921).

Turney 502

When we look up this passage it turns out that the quote about 'wretched failures' is an aside of Evans' in a reasoned context:

Crean, as already set down, had started with the Main Southern Party a week after Lashly and I had first set out as the pioneers with those wretched failures, the motor sledges.

Evans 252

The point that Evans is making is that the struggles his team had with the motorised sledges had cost them precious time and given them no advantage at all. Crean had set out a week after them and had already caught them up. In this context the motorised sledges, for which he and his team were 'pioneers' were indeed 'wretched failures' and Evans' 'public criticism' was quite justified. By leaving out the context of Evans' 'wretched failures' remark, Turney makes Evans' reasoned statement seem like merely an outburst of bitter prejudice – just another smear.

In reality, it is part of Evans's glass-half-full temperament that he was always on the lookout for positive conclusions. Even after all his struggles with these 'wretched failures' on the expedition, in almost the same breath in his memoir he balances that with a broader perpective:

As will be seen, these were long days, and although he did not say it, Day must have felt the crushing disappointment of the failure of the motors – it was not his fault, it was a question of trial and experience. Nowadays we have far more knowledge of air-cooled engines and such crawling juggernauts as tanks, for it may well be argued that Scott's motor sledges were the forerunners of the tanks.

Evans 198

We also have to note that Evans did not make these remarks 'on his return from Antarctica'. He made them in 1921, nine years after the expedition ended. Once again, Turney is distorting his account to smear Evans by impugning his loyalty. It is regrettable that Turney allows his animus towards Evans to lead him into such misrepresentations.

Scott's mistaken hopes for the motorised sledges had distorted the planning of the expedition as a whole and threatened its success from its beginnings. It may even have been a blessing that of the three motorised sledges delivered, only two came into use: one slipped and was lost in the McMurdo Sound during unloading.

Scott's sledges

Even when the motorised sledges were working, Scott had to admit that their use had not fulfilled his expectations:

On 6 January 1911, Scott remarked in his diary:

The motor sledges are working well, but not very well; the small difficulties will be got over, but I rather fear they will never draw the loads we expect of them (R. F. Scott, 1913a).

Turney 501

At this moment Scott is clearly blind to the efforts that are required to keep his motor sledges working at all. Wrecked pistons are not 'small difficulties'. Stating that the 'motor sledges are working well' is delusional, but Turney only takes the opinion of Skelton and Scott in judging the efficacy of the motor tractors:

With 'an 8–10 HP petrol motor' and two-air cooled cylinders, the sledge was designed to pull a substantial load at five kilometres an hour. By March 1910 the sledge was successfully negotiating slopes and dragging sledges in Norway, steered by an individual pulling on a rope (Skelton, 1910b). Scott hoped that the motorised sledges would be as effective in the south for transporting supplies across the Ross Ice Shelf. He later recorded in his diary:

A small measure of success [for the expedition] will be enough to show their possibilities, their ability to revolutionise Polar transport (R. F. Scott, 1913a).

Turney 500

When we remove Turney's distorting spectacles and read what Scott himself thought about his use of motor tractors as expressed in the entries in his expedition journal we find a mind torn between doubts, hopes, paranoia, deep depression and wild optimism. Let's follow briefly how the unrequited lover of motor technology copes with rejection after rejection by the objects of his desire:

I am secretly convinced that we shall not get much help from the motors, yet nothing has ever happened to them that was unavoidable. A little more care and foresight would make them splendid allies. The trouble is that if they fail, no one will ever believe this.

Scott 17 October

Quite in character, Scott transfers any blame for the inadequacies of the motors onto his subordinates. The statement 'nothing has ever happened to them that was unavoidable' is quite delusional. We sense the level of Scott's paranoid anxiety in his final sentence: 'if they fail, no one will ever believe this'. To which Roland Huntford, as rabidly anti-Scott as Turney is anti-Evans notes:

Scott's lack of 'care and foresight' was his own fault. He had ordered the designer not to bother with extra testing and low temperature trials in a freezing chamber. The designer was a fellow officer, Engineer Commander R. W. Skelton, later Chief Engineer of the Navy. He had been with Scott on the Discovery expedition, but for reasons of naval etiquette had been dropped from this one. Lt Evans had objected to having anyone of a superior rank under him as nominally second-in-command. Skelton reproached Scott with using him and then casting him aside. His design was among the first snow vehicles to use the caterpillar track, an American invention. In the hurry demanded by Scott, turning was unresolved. Only later was it achieved by letting one track move faster than the other. Scott's men turned their sledges by main force, heaving on a shaft attached to the front.

Huntford 77f

We'll leave Huntford – as anti-British as he is anti-Scott – with his gratuitous satisfaction at the (mis)use of an American invention.

Now things seem to be going better with his motors Scott cheers up a little, but knows in his heart of hearts that there may be trouble ahead:

The motor axle case was completed by Thursday morning, and, as far as one can see, Day made a very excellent job of it. Since that the Motor Party has been steadily preparing for its departure. To-day everything is ready. The loads are ranged on the sea ice, the motors are having a trial run, and, all remaining well with the weather, the party will get away to-morrow.

[…]

The temperature is up to zero about; this probably means about -20° on the Barrier. I wonder how the motors will face the drop if and when they encounter it. Day and Lashly are both hopeful of the machines, and they really ought to do something after all the trouble that has been taken.

Scott 22 October 1911

Praise for Day, who 'made a very excellent job' of a repair. Only five days before, Scott was expecting to be let down by the humans involved in working with his motors. Day, of course, is the man Turney tells us was an incompetent substitute for Skelton. Then comes more self-doubt from Scott, as he realises that the motors 'really ought to do something after all the trouble that has been taken'.

Two fine days for a wonder. Yesterday the motors seemed ready to start and we all went out on the floe to give them a 'send off.' But the inevitable little defects cropped up, and the machines only got as far as the Cape. A change made by Day in the exhaust arrangements had neglected the heating jackets of the carburetters; one float valve was bent and one clutch troublesome. Day and Lashly spent the afternoon making good these defects in a satisfactory manner.

Scott 24 October 1911

If this passage sounds familiar to you, it should. We quoted it above, but in the Turney version, which stopped after the explicit criticism of Day's neglectful modification, thus leaving out the positive that didn't fit the Turney thesis: 'Day and Lashly spent the afternoon making good these defects in a satisfactory manner.' More positive statements about Day follow this entry:

This morning the engines were set going again, and shortly after 10 A.M. a fresh start was made. At first there were a good many stops, but on the whole the engines seemed to be improving all the time. They are not by any means working up to full power yet, and so the pace is very slow. The weights seem to me a good deal heavier than we bargained for. Day sets his motor going, climbs off the car, and walks alongside with an occasional finger on the throttle. Lashly hasn’t yet quite got hold of the nice adjustments of his control levers, but I hope will have done so after a day’s practice.

Scott now gives us a paragraph of hopes, dreams and fears about his beloved motors:

I find myself immensely eager that these tractors should succeed, even though they may not be of great help to our southern advance. A small measure of success will be enough to show their possibilities, their ability to revolutionise Polar transport. Seeing the machines at work to-day, and remembering that every defect so far shown is purely mechanical, it is impossible not to be convinced of their value. But the trifling mechanical defects and lack of experience show the risk of cutting out trials. A season of experiment with a small workshop at hand may be all that stands between success and failure.

At any rate before we start we shall certainly know if the worst has happened, or if some measure of success attends this unique effort.

Scott 24 October 1911

The confusion of his thoughts, full of contradictions and non sequiturs, is remarkable – but quite characteristic for Scott. He is still radiating love for his innovations, even if 'they may not be of great help to our southern advance'. In other words, it doesn't matter if they are useless to him: in this respect the tormented lover will be satisfied with only 'a small measure of success'. We read and re-read statements such as 'every defect so far shown is purely mechanical' and can find no meaning in them at all. We are told that 'it is impossible not to be convinced of their value'. Clearly, some complex special pleading has sprung up in his mind to justify the uselessness of his objects of desire.

Scott gives us more motor optimism three days later:

Providing there is no serious accident, the engine troubles will gradually be got over; of that I feel pretty confident. Every day will see improvement as it has done to date, every day the men will get greater confidence with larger experience of the machines and the conditions. But it is not easy to foretell the extent of the result of older and earlier troubles with the rollers. The new rollers turned up by Day are already splitting, and one of Lashly’s chains is in a bad way; it may be possible to make temporary repairs good enough to cope with the improved surface, but it seems probable that Lashly’s car will not get very far.

It is already evident that had the rollers been metal cased and the runners metal covered, they would now be as good as new. I cannot think why we had not the sense to have this done. As things are I am satisfied we have the right men to deal with the difficulties of the situation.

Scott 27 October 1911

More trouble with his beloveds, but a sudden expression of confidence in his subordinates: 'we have the right men to deal with the difficulties of the situation'. You won't find this quotation in Turney, of course.

In true Scott style, this confidence will not last long, but first we have to get through some more irrational dreaming and another dose of paranoia:

The motor programme is not of vital importance to our plan and it is possible the machines will do little to help us, but already they have vindicated themselves. Even the seamen, who have remained very sceptical of them, have been profoundly impressed. Evans said, ‘Lord, sir, I reckon if them things can go on like that you wouldn’t want nothing else’ – but like everything else of a novel nature, it is the actual sight of them at work that is impressive, and nothing short of a hundred miles over the Barrier will carry conviction to outsiders.

Scott 27 October 1911

The 'motor programme is not of vital importance to our plan', 'the machines will do little to help us' but they have 'vindicated themselves' – translation: the motors haven't worked but it doesn't matter – I still love them. Scott is obsessed with the need to convince 'outsiders of the inner worth of these objects of desire. 'Evans' here is Petty Officer Edgar Evans, not Lieutenant Teddy Evans, just in case you failed to detect the below-decks accent.

Nemesis, that hater of oddities, arrived three days later, when the precious oddities disintegrated, one after the other:

Evans reported that Lashly’s motor had broken down near Safety Camp; they found the big end smashed up in one cylinder and traced it to a faulty casting; they luckily had spare parts, and Day and Lashly worked all night on repairs in a temperature of -25º. By the morning repairs were completed and they had a satisfactory trial run, dragging on loads with both motors.

On account of this accident and because some of our hardest worked people were badly hit by the two days’ absence helping the machines, I have decided to start on Wednesday instead of to-morrow.

Scott 30 October 1911

Scott has begun to realise just how much time and effort is being wasted on keeping his beloved motors running.

Camp 2. Led march – started in what I think will now become the settled order. Atkinson went at 8, ours at 10, Bowers, Oates and Co. at 11.15. Just after starting picked up cheerful note and saw cheerful notices saying all well with motors, both going excellently. Day wrote 'Hope to meet in 80°30' (Lat.).' Poor chap, within 2 miles he must have had to sing a different tale. It appears they had a bad ground on the morning of the 29th. I suppose the surface was bad and everything seemed to be going wrong. They ‘dumped’ a good deal of petrol and lubricant. Worse was to follow. Some 4 miles out we met a tin pathetically inscribed, ‘Big end Day’s motor No. 2 cylinder broken.’ Half a mile beyond, as I expected, we found the motor, its tracking sledges and all. Notes from Evans and Day told the tale. The only spare had been used for Lashly’s machine, and it would have taken a long time to strip Day’s engine so that it could run on three cylinders. They had decided to abandon it and push on with the other alone. They had taken the six bags of forage and some odds and ends, besides their petrol and lubricant. So the dream of great help from the machines is at an end! The track of the remaining motor goes steadily forward, but now, of course, I shall expect to see it every hour of the march.

Scott 4 November 1911

One motor tractor has broken down irreparably: 'the dream of great help from the machines is at an end!' Scott follows the track of the remaining motor, expecting to come across its corpse, too, before long. He does, two days later:

Camp 4. We started in the usual order, arranging so that full loads should be carried if the black dots to the south prove to be the motor. On arrival at these we found our fears confirmed. A note from Evans stated a recurrence of the old trouble. The big end of No. 1 cylinder had cracked, the machine otherwise in good order. Evidently the engines are not fitted for working in this climate, a fact that should be certainly capable of correction. One thing is proved; the system of propulsion is altogether satisfactory. The motor party has proceeded as a man-hauling party as arranged.

Scott 6 November 1911

We have already noticed the lover's delusion in some of these words in a quotation from Turney: 'The big end of No. 1 cylinder had cracked, the machine otherwise in good order'. True to form, Turney stopped here, characteristically omitting to give us the next sentences that reinforces Scott's delusion at this point.

Turney's presentation of Evans as a half-hearted, luddite motor-tractor user and of Day as a bungling incompetent is a travesty of the real efforts both men made in order to make a success of Scott's decision to used motorised hauling. Scott himself, gazing at the corpse, doubles down on his delusional love: 'One thing is proved; the system of propulsion is altogether satisfactory'. It was all in his plan, he tells us: 'The motor party has proceeded as a man-hauling party as arranged'. There comes a point where the historian has to call in the shrinks.

We remind ourselves: according to Turney the failure of the motorised sledges was Evans' fault. In fact, the reality was just the opposite. It is not possible to refute Turney's impressionistic smears and selective quoting in a few words, but the true extent of the efforts of the team can be judged from Evans' own account of that part of the journey, an account the veracity of which has never been questioned.

Evans's sledges

Those who read Evans' account of the expedition South with Scott will find a detailed and extremely balanced section on the team's struggle with the motorised sledges. Where Scott is bitter and paranoid, Evans is cheerfully generous and unfailingly balanced in his judgments:

Day, Nelson, and Lashly worked with the motor sledges; the newest motor frequently towed loads of 2500 lb. over the ice at a six mile an hour speed. The oldest hauled a ton and managed six double trips a day. Day, the motor engineer, had been down here before — both he and Priestley came from the Shackleton Expedition. The former had a decidedly comic vein which made him popular all round. From start to finish Day showed himself to be the most undefeated sportsman, and it was not his fault that the motor sledges did badly in the end.

Evans 70

The quoted section reproduced below is not as brief as one would like, but it gives a good insight into what Evans, Day and Lashly went through with these 'wretched failures' and how much effort they put into making the use of them deliver at least some results. The length of this quotation is a good example of the lengths to which we must go to refute just one of Turney's one line smears: 'Evans was publicly critical of the sledges on his return from Antarctica'.

Evans' account is complementary to Scott's account, since it covers the work of the motorised sledge party from the perspective of Teddy Evans, its leader. The following extracts will give readers a flavour of the problems, the heroic and goal-oriented work of the team and the character of Teddy Evans, its author.

On October 24, 1911, the advance guard of the Southern Party, consisting of Day, Lashly, Hooper, and myself, left Cape Evans with two motor sledges as planned. We had with us three tons of stores, pony food, and petrol, carried on five 12 ft. sledges, and our own tent, etc., on a smaller sledge. The object of sending forward such a weight of stores was to save the ponies' legs over the variable sea ice, which was in some places hummocky and in others too slippery to stand on. Also the first thirty miles of Barrier was known to be bad travelling and likely to tire the ponies unnecessarily unless they marched light, so here again it was desirable to employ the motors for a heavy drag.

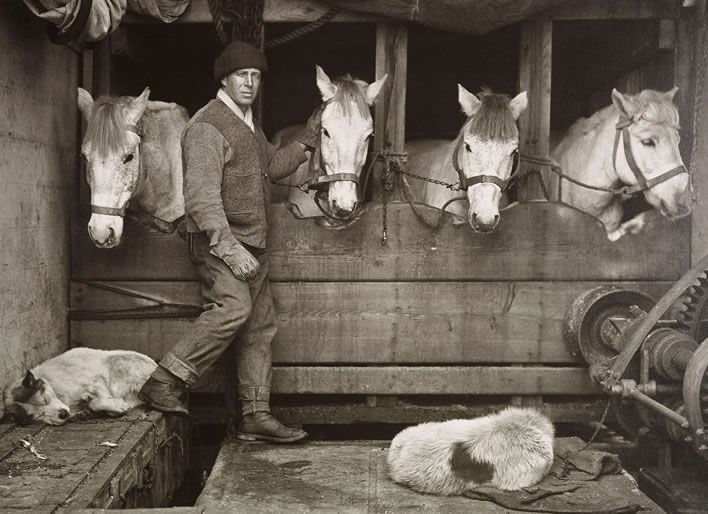

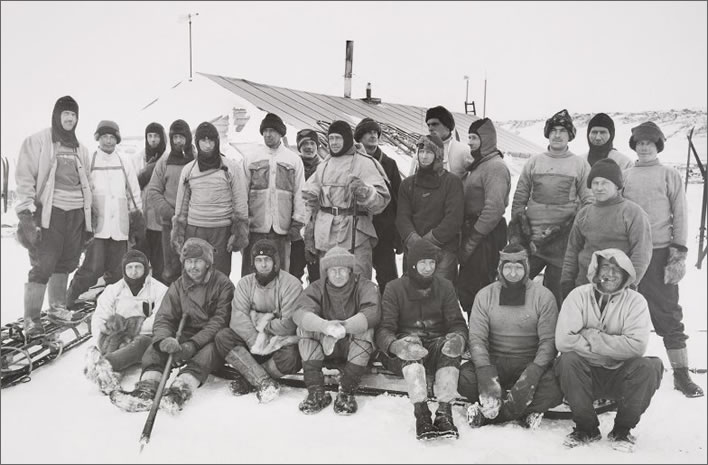

The Motor Party, with its ever cheerful leader Teddy Evans: (l-r) Day, Lashly, Hooper and Evans. October 1911. Image: Photographer Herbert Ponting. British Antarctic Expedition 1910-13 (Ponting Collection), P2005/5/572.

We had fine weather when at 10.30 a.m. we started off, with the usual concourse of wellwishers, and after one or two stops and sniffs we really got under way, and worked our loads clear of the Cape on to the smoother stretch of sea ice, which improved steadily as we proceeded. Hooper accompanied Lashly's car and I worked with Day.

A long shaft protruded 3 ft. clear each end of the motors. To the foremost end we attached the steering rope, just a set of man-harness with a long trace, and to the after end of the shaft we made fast the towing lanyard or span according to whether we hauled sledges abreast or in single line. Many doubts were expressed as to the use of the despised motors—but we heeded not the gibes of our friends who came out to speed us on our way.

[…]

We made a mile an hour speed to begin with and stopped at Razorback Island after 3½ miles.

We had lunch at Razorback, and after that we "lumped," man-hauled, and persuaded the two motors and three tons of food and stores another mile onward. The trouble was not on account of the motors failing, but because of a smooth, blue ice surface. We camped at 10 p.m. and all slept the sleep of tired men. October 25 was ushered in with a hard wind, and it appeared in the morning as if our cars were not going to start. We had breakfast at 8 a.m. and got started on both motors at 10.45, but soon found that we were unable to move the full loads owing to the blue ice surface, so took to relaying. We advanced under three miles after ten hours' distracting work – mostly pulling the sledges ourselves, jerking, heaving, straining, and cursing—it was tug-of-war work and should have broken our hearts, but in spite of our adversity we all ended up smiling and camped close on 9 p.m.

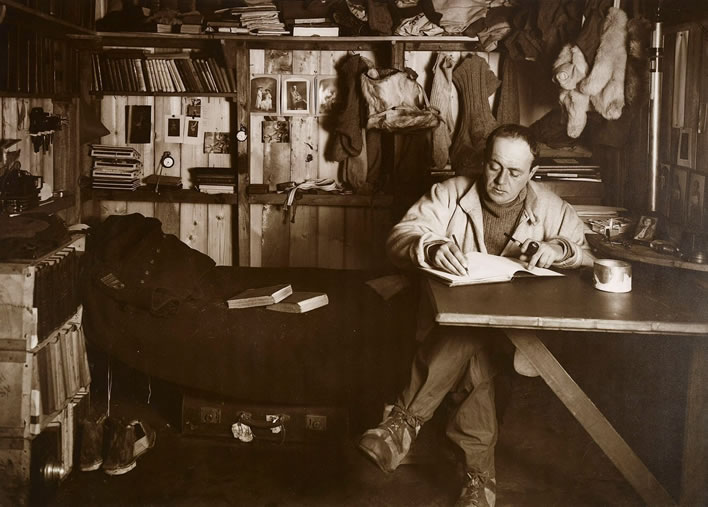

Teddy Evans (front) and Bernard Day with a motor tractor. The design fault that made the motor tractors so useless on Antarctic surfaces, irrespective of whether their engines worked or not, is clear on a moment's reflection. The tractor was attempting to drag a dead weight without having any corresponding weight above the tracks to provide enough downward force for the grip required. On any slippery surface it could never hope to drag the dead weights of the sledges. (This is why railway locomotives are always heavy.) If this arrangement is Skelton's design then it is a very bad one. Image: Photographer Herbert Ponting. British Antarctic Expedition 1910-13 (Ponting Collection), P2005/5/991.

[…]

Captain Scott and seven others came up with us at 2 p.m., but both motors were then forging ahead, so they went on to Hut Point without waiting.

[…]

The motor engines were certainly good in moderate temperatures, but our slow advance was due to the chains slipping on hard ice. Scott was concerned, but he made it quite clear that if we got our loads clear of the Strait between White Island and Ross Isle, he would be more than satisfied.

[…]

On October 27 I woke the cooks at 6.30 a.m., and we breakfasted about 8 o'clock, then went up to the motors off Cape Armitage. Lashly's car got away and did about three miles with practically no stop. Our carburettor continually got cold, and we stopped a good deal. Eventually about 1 p.m. we passed Lashly's car and made our way up a gentle slope on to the Barrier, waved to the party, and went on about three-quarters of a mile.

Here we waited for Lashly and Hooper, who came up at 2.30, having had much trouble with their engine, due to overheating, we thought. When Day's car glided from the sea ice, over the tide crack and on to the Great Ice Barrier itself, Scott and his party cheered wildly, and Day acknowledged their applause with a boyish smile of triumph.

As soon as Lashly got on to the Barrier, Scott took his party away and they returned to Cape Evans. It would have been a disappointment to them if they had known that we shortly afterwards heard an ominous rattle, which turned out to be the big end brass of one of the connecting rods churning up – due to a bad casting.

Bernard Day working on the engine of one of the motor tractors. Mount Erebus is in the background. October 1911. This image is close to base. Imagine the problems of open-air maintenance, attempting to use tools with gloved hands in extremely low temperatures. Image: Photographer Herbert Ponting. British Antarctic Expedition 1910-13 (Ponting Collection), P2005/5/568.

Luckily we had a spare, which Day and Lashly fitted, while Hooper and I went on with the 10 ft. sledge to Safety Camp.

Here we dug out our provisions according to instructions and brought them back to our camp to avoid further delay in repacking sledges. We then made Day and Lashly some tea to warm them up. They worked nobly and had the car ready by 11 p.m. We pushed on till midnight in our anxiety to acquit ourselves and our motors creditably. The thermometer showed -19.8° on camping, and temperature fell to -25° during the night.

[…]

I caught the motors late in the afternoon after running nine miles; they had only done three miles whilst I had been doing fifteen. We continued crawling along with our loads, stopping to cool the engines every few minutes, it seemed, but at 11 p.m. they overheated to such an extent that we stopped for the night.

[…]

We intentionally lay in our bags until 8.30 next morning, but didn't get those dreadful motors to start until 10.45 a.m. Even then they only gave a few sniffs before breaking down and stopping, so that we could not advance perceptibly until 11.30. We had troubles all day, and were forced to camp on account of Day's sledge giving out at 5 p.m, – we daren't stop for lunch earlier, for once stopped one never could say when a re-start could be made.

[…]

Started off at six and soon found that the big end brass on No. 2 cylinder of this sledge had given out, so dropped two more tins of petrol and a case of filtrate oils. We thereupon continued at a snail's pace, until at 9.15 the connecting rod broke through the piston. We decided to abandon this sledge, and made a depot of the spare clothing, seal meat, Xmas fare, ski belonging to Atkinson and Wright, and four heavy cases of dog biscuit. I left a note in a conspicuous position on the depot, which we finished constructing at midnight. We wasted no time in turning in.

[…]

After breakfast we dug out sledges, and Lashly and Day got the snow out of the motor, a long and rotten job. The weather cleared about 11 a.m. and we got under way at noon. It turned out very fine and we advanced our weights 7 miles 600 yards, camping at 10.40 p.m.

Bernard Day digging out a snowed up motor tractor. August 1911. This is taken close to base. Both of the expedition's motor tractors are visible, together with a spare set of tracks. This image makes it clear that we should not overlook the draining effects of the peripheral labour involved in the use of the tractors. Image: Photographer Herbert Ponting. British Antarctic Expedition 1910-13 (Ponting Collection), P2005/5/467.

As will be seen, these were long days, and although he did not say it, Day must have felt the crushing disappointment of the failure of the motors – it was not his fault, it was a question of trial and experience. Nowadays we have far more knowledge of air-cooled engines and such crawling juggernauts as tanks, for it may well be argued that Scott's motor sledges were the forerunners of the tanks.

On November 1 we advanced six miles and the motor then gave out. Day and Lashly gave it their undivided attention for hours, and the next day we coaxed the wretched thing to Corner Camp and ourselves dragged the loads there.

Arrived at this important depot we deposited the dog pemmican and took on three sacks of oats, but after proceeding under motor power for 1½ miles, the big end brass of No. 1 cylinder went, so we discarded the car and slogged on foot with a six weeks' food supply for one 4-man unit. Our actual weights were 185 lb. per man. We got the whole 740 lb. on to the 10 ft. sledge, but with a head wind it was rather a heavy load. We kept going at a mile an hour pace until 8 p.m.

I had left a note at the Corner Camp depot which told Scott of our trying experiences : how the engines overheated so that we had to stop, how by the time they were reasonably cooled the carburettor would refuse duty and must be warmed up with a blow lamp, what trouble Day and Lashly had had in starting the motors, and in short how we all four would heave with all our might on the spans of the towing sledges to ease the starting strain, and how the engines would give a few sniffs and then stop—but we must not omit the great point in their favour : the motors advanced the necessaries for the Southern journey 51 miles over rough, slippery, and crevassed ice and gave the ponies the chance to march light as far as Corner Camp — this is all that Oates asked for.

It was easier work now to pull our loads straightforwardly South than to play about and expend our uttermost effort daily on those "qualified" motors. Even Day confessed that his relief went hand in hand with his disappointment.

Evans 191-199

Anyone reading this who has spent precious days of their youth trying to get even the engine technology of the fifties to work will still remember the relief when the offending vehicle was eventually towed off to the scrapyard or sold to another idiot. With that in mind, this remark of Evans will sound very familiar:

We were very happy in our party, and when cooking we all sang and yarned, nobody ever seemed tired once we got quit of the motors.

Evans 200

Food and supplies

Turney's most serious slander of Evans is the assertion that on the return journey from the south, Evans consumed more than his fair share of rations. Scott's team were following in their tracks, around 24 days behind them. According to Turney, this shortage of rations was a contributory factor in the failure of Scott's team and their ultimate demise only 11 miles from One Ton depot.

Turney implies that the motive for this disgraceful behaviour arose from Evans' resentment that Scott did not choose him to join the team that went to the South Pole. As if this motive were not enough, Turney adds that Evans was afflicted by scurvy on the return journey (his own fault, of course, according to Turney) and helped himself to extra rations because of that.

This is an outrageous accusation, which can be easily dismissed by the fact that, on that return journey, Evans was never alone. He was in a team of three and the alleged pilfering of food would at a minimum have been noticed by the others, Crean and Lashly, unless, of course, we are prepared to imagine Evans lurking outside the tent secretely snaffling biscuits and pemmican from the depot. In Turney's twisted world all three of them would have had to have been conspirators or participants in the cheating. Crean and Lashly have no known motive for doing this.

Such a brief refutation might be enough for the sane, but unfortunately we are in Turney's world – a place full of deranged impressionistic smears against the hated Teddy Evans. Faced with such slanders, it is not enough to say that the speculations are obviously absurd – 9/11 on ice – we need to show that Turney's accusations cannot possibly be true.

Food, glorious food

There is no doubt that Teddy Evans liked his food – anyone reading his account of the polar expedition will be touched by his repeated tales of welcome meals. One highpoint was reached at the Midwinter Day feast in Camp Evans on 22 June 2011, the menu for which Evans reproduces in loving detail in South with Scott. [Evans 134] His readers will also be touched by his repeated tales of hunger. Scott also confides his sufferings of hunger to his diary, but without Evans' humour or pictorial imagination. All the trekking parties suffered from insufficient food for a number of reasons.

Rations too small

Firstly, Scott's calculation of the food requirements of the expedition were based on a very low daily calorific requirement. In Scott's defence we must say that nutrition at the beginning of the 20th century was not the precise science it is now. Men who are pulling sledges over refractory surfaces in extreme cold require a huge calorie intake to function properly. Anything less than that intake moves the men into a starvation zone.

A four man sledge team manhauling.

Charles Wright, one of the geologists on the team and a member of Evans' man-hauling party, experienced at first hand the food deprivation that this team in particular suffered. Compared to Evans and Lashly, who had man-hauled from Corner Camp, his own exposure to hunger was limited. The core man-hauling team was Teddy Evans and Lashly, who had already man-hauled from Corner Camp. Atkinson joined them after his pony was shot, and now Wright arrived after the execution of his pony, Chinaman:

I was very pleased indeed that I had nursed Chinaman and saved him so long from the dogs, but I ate him without compunction.

Cherry has expressed his opinion in The Worst Journey [in the World] that we should have cached more pony meat at the cairns for our own use with some additional fuel…. I think Cherry was right in principle and at least some more care might have been taken in burying the cached pony meat at the bottom of the Beardmore Glacier when all the remaining ponies were shot.

Of course, it is very easy to be wise after the event, but the man-hauling party was very, very hungry after little over a month on our way.

Wright 203 [28 November 1911]

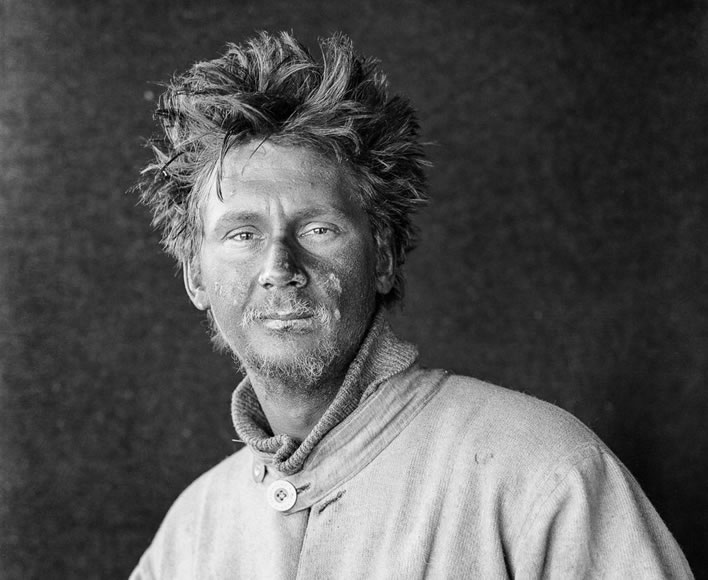

A frostbitten Charles Wright after his return to the camp at Cape Evans with the First Support Party. January 1912. Image: Photographer Herbert Ponting. British Antarctic Expedition 1910-13 (Ponting Collection).

Without pony meat, the basic rations predestined these physical labourers to starvation.

Furthermore, as any modern sportsman or woman knows, that intake has to be balanced in type – carbohydrate, fat and protein – to match the circumstances. There was no concept of this at the time and no idea of the existence of vitamins and the need for minerals. In effect, all Scott's trekkers and haulers were suffering from chronic malnutrition. They were surviving on starvation provisions almost all of the time.

Inadequate depots

Secondly, Scott's calculations assumed that all the other parts of his plan worked perfectly: men walking alongside the motorised sledges and the ponies for the expected distances under the expected conditions. The men would have been hungry even if all had gone to plan, but men dragging large sledges, erecting tents, trudging along all day, battling cold and damp and taking two or three times as long to reach depots pushed gnawing hunger into serious starvation.

In Scott's detailed account of his team's journey back from the Pole the reader will notice the remark, again and again, that even when the specified supplies are present, even when they have 'good food' and even 'extra food', the team is permanently hungry. They have, for example, on 22 January '5 days' food in hand'; two days later, trudging uphill, the situation is 'scant food'.

Depots too far apart

Thirdly, Scott was a planning optimist. He had no reserves to cover the times when things did not run to plan, particularly that most unpredictable factor, weather, which is what killed him and his polar party. Eight days pinned down in a cold, wet tent in a blizzard with only two days' supply of food and almost no heating fuel is bad luck, but when bad luck struck again and again they had no reserves to survive it. It is a testament to the endurance of the three returning teams that they got as far as they did under the terrible circumstances.

Consequently, given the cold and the physical effort, all the trekking members of Scott's expedition were living on emergency rations as a normal case. When the worst case occurred, as it always must, there were no reserves to cope – emergency rations became starvation rations. That failure, combined with his optimism about the speed of travel of men dragging sledges over resistant snow at extremly low temperature killed him and his group.

A four man sledge team manhauling. 1912. The wheel behind the sledge is the 'sledge-meter' that, when it worked, gave an approximate indication of distance travelled.

On the march, Scott's assumption had also been that there would always be units of four men. Scott's decision to take a group of five on to the pole and to leave Evans' team a man short was a serious logistical error which has been criticised by many later commentators. Evans himself did not realise the danger of that decision until it was almost too late:

On January 3 Scott came into my tent before we began the day's march and informed me that he was taking his own team to the Pole. He also asked me to spare Bowers from mine if I thought I could make the return journey of 750 miles short-handed – this, of course, I consented to do, and so little Bowers left us to join the Polar party.

On 4th January we took four days' provision for three men and handed over the rest of our load to Scott.

[…]

Reluctant as I was to confess it to myself, I soon realised that the ceding of one man from my party had been too great a sacrifice, but there was no denying it, and I was eventually compelled to explain the situation to Lashly and Crean and lay bare the naked truth. No man was ever better served than I was by these two ; they cheerfully accepted the inevitable, and throughout our homeward march the three of us literally stole minutes and seconds from each day in order to add to our marches, but it was a fight for life.

[…]

As mile after mile was covered our thoughts wandered from the Expedition to those in our homeland, and thought succeeded thought while the march progressed until the satisfying effect of the last meal had vanished and life became one vast yearning for food.

Evans 234-7

Far from robbing Scott of supplies, Evans had inadvertently robbed himself and his own team at the start of their journey north. It was a mistake he accepted and about which he was quite open in his 1921 account of the journey. His team made up the shortfall by exceptionally long marching days and by taking a breakneck shortcut over the Beardmore icefalls.

Fuel shortages

The greatest setback in provisioning was the leaking of fuel oil from the storage cans. The now generally accepted explanation is that the leather seals in the caps were affected by the cold and allowed the fuel to dribble out. Do we need to state the obvious that in Antarctic temperatures the loss of heating fuel was a serious matter – just as serious as the lack of food, since without either of them a team was doomed.

Even Turney cannot blame Evans for this mishap. As the editors noted in a footnote on the issue in the first edition of Scott's journals, the problem was just another of those unforeseens in the planning of the expedition that doomed any chance of its success:

At this, the Barrier stage of the return journey, the Southern Party were in want of more oil than they found at the depots. Owing partly to the severe conditions, but still more to the delays imposed by their sick comrades, they reached the full limit of time allowed for between depots. The cold was unexpected, and at the same time the actual amount of oil found at the depots was less than they had counted on.

The worst time came on the Barrier; from Lower Glacier to Southern Barrier Depot (51 miles), 6½ marches as against 5 (two of which were short marches, so that the 5 might count as an easy 4 in point of distance); from Southern Barrier to Mid Barrier Depot (82 miles), 6½ marches as against 5½; from Mid Barrier to Mt. Hooper (70 miles), 8 as against 4¾, while the last remaining 8 marches represent but 4 on the outward journey. […]

As to the cause of the shortage, the tins of oil at the depots had been exposed to extreme conditions of heat and cold. The oil was specially volatile, and in the warmth of the sun (for the tins were regularly set in an accessible place on the top of the cairns) tended to become vapour and escape through the stoppers even without damage to the tins. This process was much accelerated by reason that the leather washers about the stoppers had perished in the great cold. Dr. Atkinson gives two striking examples of this.

1. Eight one-gallon tins in a wooden case, intended for a depot at Cape Crozier, had been put out in September 1911. They were snowed up; and when examined in December 1912 showed three tins full, three empty, one a third full, and one two-thirds full.

2. When the search party reached One Ton Camp in November 1912 they found that some of the food, stacked in a canvas 'tank' at the foot of the cairn, was quite oily from the spontaneous leakage of the tins seven feet above it on the top of the cairn.

The tins at the depots awaiting the Southern Party had of course been opened and the due amount to be taken measured out by the supporting parties on their way back. However carefully re-stoppered, they were still liable to the unexpected evaporation and leakage already described. Hence, without any manner of doubt, the shortage which struck the Southern Party so hard.

Scott 441 (Appendix, Note 26, p. 401.)

Turney likes to draw our focus onto supplies that were 'inexplicably missing'. Anyone reading the accounts of the polar group's supply situation contained in Scott's journal will become aware that the greatest shortage of supplies related to fuel oil (that had leaked out) – Scott, according to his journal, always had more food than fuel available.

The missing food smear

Turney places much emphasis on the complaints relayed through their widows by Scott and Wilson, and some remarks in Scott's journal. These are largely the complaints of men whose plans have collapsed and who are struggling to cope with the changed reality of their situation. The slightest setback reported in these journals triggers the bereaved into a state of concern. If these are the only viewpoints reported then the reader receives a very distorted view of events.

In dealing with this subject we must also distinguish very carefully between food rations and fuel rations. The only sure way to deal with Turney's missing food smear is to put Scott's remarks in context by making a table of the storage depots with the dates on the return journey when the various parties reached them.

Supplies on the return journeys of Scott and Evans

Legend:

Food supply | Fuel supply | Dogs | Discussion points | Text not published

| Depots etc. | Evans'/Lashly's accounts | Scott's journal |

| [Parting of Scott and Evans. Scott heads south to the Pole, Evans north to base camp.] |

03.01

He also asked me to spare Bowers from mine if I thought I could make the return journey of 750 miles short-handed — this, of course, I consented to do, and so little Bowers left us to join the Polar party. Captain Scott said he felt that I was the only person capable of piloting the last supporting party back without a sledge meter. |

03.01

Bowers is to come into our tent, and we proceed as a five man unit to-morrow. We have 5½ units of food – practically over a month's allowance for five people – it ought to see us through. |

|

04.01

we took four days' provision for three men and handed over the rest of our load to Scott. |

04.01

The second party had followed us in case of accident, but as soon as I was certain we could get along we stopped and said farewell. […] I was glad to find their sledge is a mere nothing to them, and thus, no doubt, they will make a quick journey back. |

|

|

05.01

We had to make average daily marches of 17 miles in order to remain on full provisions whilst returning over that featureless snow-capped plateau. |

05.01

Cooking for five takes a seriously longer time than cooking for four; perhaps half an hour on the whole day. It is an item I had not considered when re-organising. |

|

|

10.01

Built cairn and left one week's food together with sundry articles of clothing. We are down as close as we can go in the latter. We go forward with eighteen days' food. Yesterday I should have said certain to see us through, but now the surface is beyond words, and if it continues we shall have the greatest difficulty to keep our march long enough. |

||

|

13.01

To-morrow we depot a week's provision , lightening altogether about 100 lbs. |

||

| Last | - |

15.01

here we leave our last depot – only four days' food and a sundry or two. |

| South Pole | - |

17.01

We have had a fat Polar hoosh in spite of our chagrin, and feel comfortable inside – added a small stick of chocolate and the queer taste of a cigarette brought by Wilson. |

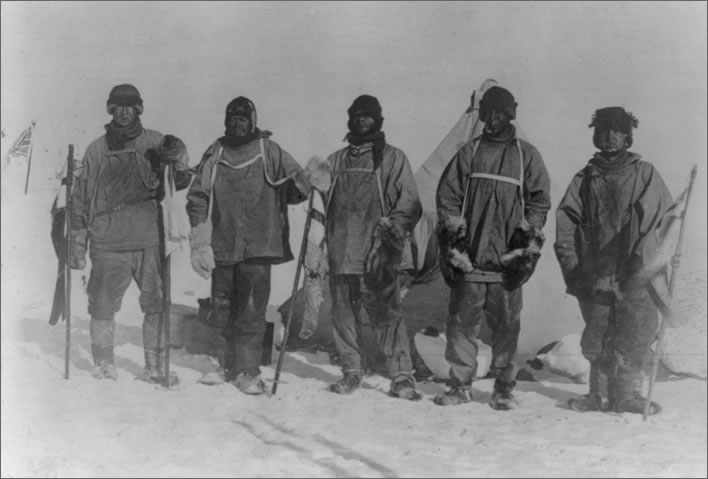

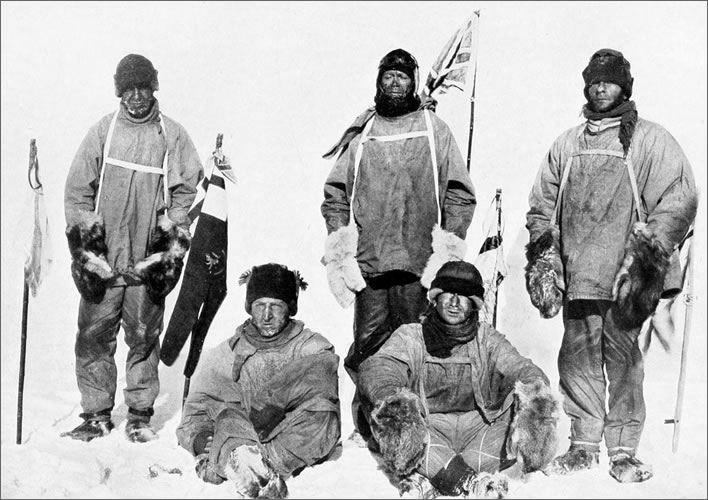

Four of the Polar Party standing disconsolately around Amundsen's tent at the South Pole. 18 January 1912.Image: Library of Congress. [Click to open a larger image in a new tab.]

The Polar Party – (l-r) Evans, Scott, Oates, Wilson and Bowers – at their camp at the South Pole. 18 January 1912. Image: Library of Congress, J195226.

The Polar Party, a picture of desolation: Wilson, Scott, Oates standing; Bowers and Edgar Evans sitting. 18 January 1912. [Click to open a larger image in a new tab.]

| Last | - |

20.01

our Southern Depot, and we pick up 4 days' food. We carry on 7 days from to-night with 55 miles to go to the Half Degree Depot made on January 10. |

|

21.01

45 miles to the next depot and 6 days' food in hand – then pick up 7 days' food (T. -22°) and 90 miles to go to the 'Three Degree' Depot. |

||

|

22.01

We are within 2½ miles of the 64th camp cairn, 30 miles from our depot, and with 5 days' food in hand. |

||

|

24.01

Is the weather breaking up? If so, God help us, with the tremendous summit journey and scant food . |

||

| 1½ Degree | - |

25.01

We had lunch and left with 9½ days' provisions […] Needless to say I shall sleep much better with our provision bag full again. The only real anxiety now is the finding of the Three Degree Depot. |

|

27.01

We are slowly getting more hungry, and it would be an advantage to have a little more food, especially for lunch . If we get to the next depot in a few marches (it is now less than 60 miles and we have a full week's food ) we ought to be able to open out a little, but we can't look for a real feed till we get to the pony food depot. |

||

|

28.01

If this goes on and the weather holds we shall get our depot without trouble. I shall indeed be glad to get it on the sledge. We are getting more hungry , there is no doubt. The lunch meal is beginning to seem inadequate . […] We talk of food a good deal more, and shall be glad to open out on it. |

||

|

29.01

We are certainly getting hungrier every day . The day after to-morrow we should be able to increase allowances . |

||

|

3 Degree

[Evans and Scott are now following the same route, Scott 24 days later than Evans.] |

06.01 | 30.01 |

|

01.02

It ought to be easy to get in with a margin, having 8 days' food in hand (full feeding). We have opened out on the 1/7th increase and it makes a lot of difference. |

||

|

02.02

The extra food is certainly helping us, but we are getting pretty hungry. The weather is already a trifle warmer and the altitude lower, and only 80 miles or so to Mount Darwin [Upper Glacier depot]. |

||

|

03.02

The extra food is doing us all good , but we ought to have more sleep. |

||

|

04.02

Thank the Lord we have good food at each meal , but we get hungrier in spite of it. |

||

|

06.02

Food is low and weather uncertain, so that many hours of the day were anxious; but this evening, though we are not as far advanced as I expected, the outlook is much more promising. |

||

|

13.01

[Risky but successful descent of the Bearmore icefalls.] So we pitched our little tent, had a good filling meal, and then, delighted with our progress, we marched on until 8 p.m. |

||

|

Upper Glacier

[Scott 24 days later than Evans.] |

14.01

Here we took 3½ days' stores as arranged , and after sorting up and repacking the depot had lunch and away down the Glacier, |

07.02

First panic, certainty that biscuit-box was short. Great doubt as to how this has come about, as we certainly haven't over-issued allowances. Bowers is dreadfully disturbed about it. The shortage is a full day's allowance . […] and what with hot tea and good food , we started the afternoon in a better frame of mind […] Soon after 6.30 we saw our depot easily and camped next it at 7.30 . |

|

09.02

Our food satisfies now , but we must march to keep in the full ration |

||

|

16.01

a pleasant day, its ending peaceful, with a sufficiency of excellent sledging rations and the promise of a similar day to succeed it. |

||

|

11.02

To-morrow's lunch must serve for two if we do not make big progress. It was a test of our endurance on the march and our fitness with small supper . We have come through well. |

||

|

12.02

after a very short supper and one meal only remaining in the food bag ; the depot doubtful in locality. |

||

|

Mid Glacier

[Scott 27 days later than Evans.] |

17.01

camped and made some tea before marching on to the depot, which lay but a few miles from us. We ate the last of our biscuits at this camp and finished everything but tea and sugar , then, new men, we struck our little camp, harnessed up and swept down over the smooth ice with scarcely an effort needed to move the sledge along. When we reached the depot we had another meal and slept through the night and well on into the next day. |

13.02

At 9 we got up, deciding to have tea, and with one biscuit, no pemmican, so as to leave our scanty remaining meal for eventualities . […] Then suddenly Wilson saw the actual depot flag. It was an immense relief, and we were soon in possession of our 3½ days' food . The relief to all is inexpressible; needless to say, we camped and had a meal. […] In future food must be worked so that we do not run so short if the weather fails us. We mustn't get into a hole like this again . Greatly relieved to find that both the other parties got through safely. |

|

18.01

The next day I had an awful attack of snow blindness , but the way down the glacier was so easy that it did not matter. [Lashly] To-night Mr. Evans is complaining of his eyes, more trouble ahead! |

||

|

14.02

We can't risk opening out our food again, and as cook at present I am serving something under full allowance. |

||

|

15.02

We have reduced food , also sleep; feeling rather done. Trust 1½ days or 2 at most will see us at depot. |

||

|

16.02

We are on short rations with not very short food; spin out till to-morrow night . We cannot be more than 10 or 12 miles from the depot |

||

|

Lower Glacier

[Scott 27 days later than Evans.] |

21.01

[Lashly] Mr. Evans is a lot better to-night |

17.02

[Death of Edgar Evans] |

|

18.02

At Shambles Camp. […] Here with plenty of horsemeat we have had a fine supper, to be followed by others such, and so continue a more plentiful era if we can keep good marches up . |

||

|

19.02

but, above all, we have our full measure of food again . To-night we had a sort of stew fry of pemmican and horseflesh, and voted it the best hoosh we had ever had on a sledge journey. |

||

|

22.01

[Lashly] Mr. Evans complained to me while outside the tent that he had a stiffness at the back of his legs behind the knees. I asked him what he thought it was, and he said could not account for it, so if he dont soon get rid of it I am to have a look and see if anything is the matter with him, as I know from what I have seen and been told before the symptoms of scurvy is pains and swelling behind the knee round the ankle and loosening of the teeth, ulcerated gums. |

22.02

To-night we had a pony hoosh so excellent and filling that one feels really strong and vigorous again . |

|

|

23.01

[Lashly] Mr. Evans seems better to-day. |

||

|

South Barrier

[Scott 30 days later than Evans.] |

25.01

- |

24.02

Found store in order except shortage oil – shall have to be _very_ saving with fuel – otherwise have ten full days' provision from to-night and shall have less than 70 miles to go. […] Short note from Evans, not very cheerful, saying surface bad, temperature high. Think he must have been a little anxious. It is an immense relief to have picked up this depot and, for the time, anxieties are thrust aside . […] It is great luck having the horsemeat to add to our ration. To-night we have had a real fine 'hoosh' . |

|

25.02

Very much easier – write diary at lunch – excellent meal – now one pannikin very strong tea – four biscuits and butter . |

||

|

26.02

We are doing well on our food, but we ought to have yet more . I hope the next depôt, now only 50 miles, will find us with enough surplus to open out . The fuel shortage still an anxiety . […] We want more food yet and especially more fat . Fuel is woefully short . |

||

|

27.02

We are naturally always discussing possibility of meeting dogs, where and when, &c. It is a critical position. We may find ourselves in safety at next depôt, but there is a horrid element of doubt. […] 31 miles to depôt, 3 days' fuel at a pinch , and 6 days' food . Things begin to look a little better; we can open out a little on food from to-morrow night , I think. |

||

|

28.02

Things must be critical till we reach the depôt, and the more I think of matters, the more I anticipate their remaining so after that event. Only 24 1/2 miles from the depôt. […] Splendid pony hoosh sent us to bed and sleep happily |

||

|

29.02

Next camp is our depôt and it is exactly 13 miles. It ought not to take more than 1½ days; we pray for another fine one. The oil will just about spin out in that event, and we arrive 3 clear days' food in hand . |

||

|

28.01

[Lashly] Mr. Evans is still very loose in his bowels. This, of course, hinders us, as we have had to stop several times. |

||

|

29.01

[Lashly] Mr. Evans is still suffering from the same complaint: have come to the conclusion to stop his pemmican, as I feel that it have got something to do with him being out of sorts. Anyhow we are going to try it. Gave him a little brandy and he is taking some chalk and opium pills to try and stop it. His legs are getting worse and we are quite certain he is suffering from scurvy, at least he is turning black and blue and several other colours as well. |

||

|

Mid Barrier

[Scott 30 days later than Evans.] |

30.01

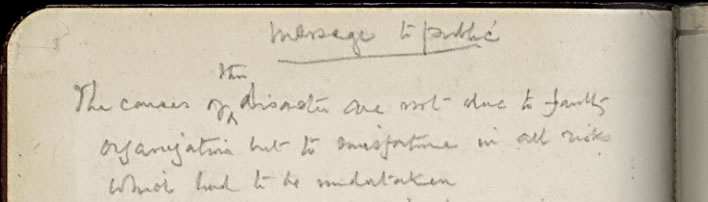

By this time I had made the unpleasant discovery that I was suffering from scurvy . It came on with a stiffening of the knee joints, then I could not straighten my legs, and finally they were horrible to behold, swollen, bruised, and green. As day followed day my condition became worse: my gums were ulcerated and my teeth loose. Then finally I got haemorrhage. [Lashly] Very bad light but fair wind, picked up the depôt this evening. Did the 14 miles quite in good time, after taking our food we found a shortage of oil and have taken what we think will take us to the next depôt. There seems to have been some leakage in the one can, but how we could not account for that we have left a note telling Capt. Scott how we found it, but they will have sufficient to carry them on to the next depôt, but we all know the amount of oil allowed on the Journey is enough, but if any waste takes place it means extra precautions in the handling of it. Mr. Evans is still without pemmican and seems to have somewhat recovered from the looseness, but things are not by a long way with him as they should be. Only two more depôts now to pick up. |

01.03

we found a shortage of oil; with most rigid economy it can scarce carry us to the next depôt on this surface (71 miles away) |

|

04.03

We are about 42 miles from the next depôt and have a week's food , but only about 3 to 4 days' fuel — we are as economical of the latter as one can possibly be, and we cannot afford to save food and pull as we are pulling . […] Providence to our aid! We can expect little from man now except the possibility of extra food at the next depôt . [ A poor one ] It will be real bad if we get there and find the same shortage of oil . |

||

|

05.03

We went to bed on a cup of cocoa and pemmican solid with the chill off […] We started march on tea and pemmican as last night — we pretend to prefer the pemmican this way. […] We are two pony marches and 4 miles about from our depôt. Our fuel dreadfully low |

||

|

06.03

We are making a spirit lamp to try and replace the primus when our oil is exhausted . It will be a very poor substitute and we've not got much spirit. If we could have kept up our 9-mile days we might have got within reasonable distance of the depôt before running out. |

||

|

07.03

We are 16 from our depôt. If we only find the correct proportion of food there and this surface continues, we may get to the next depôt [Mt. Hooper, 72 miles farther] but not to One Ton Camp. We hope against hope that the dogs have been to Mt. Hooper ; then we might pull through. If there is a shortage of oil again we can have little hope . |

||

|

Mt. Hooper

[Scott 34 days later than Evans.] |

04.02

[Lashly] we arrived at the depôt at 7.40 P.M. We are now 180 miles from Hut Point, and this Sunday night we hope to be only two more Sundays on the Barrier. No improvement in Mr. Evans, much worse. We have taken out our food and left nearly all the pemmican as we dont require it on account of none of us caring for it, therefore we are leaving it behind for the others. They may require it. We have left our note and wished them every success on their way, but we have decided it is best not to say anything about Mr. Evans being ill or suffering from scurvy. |

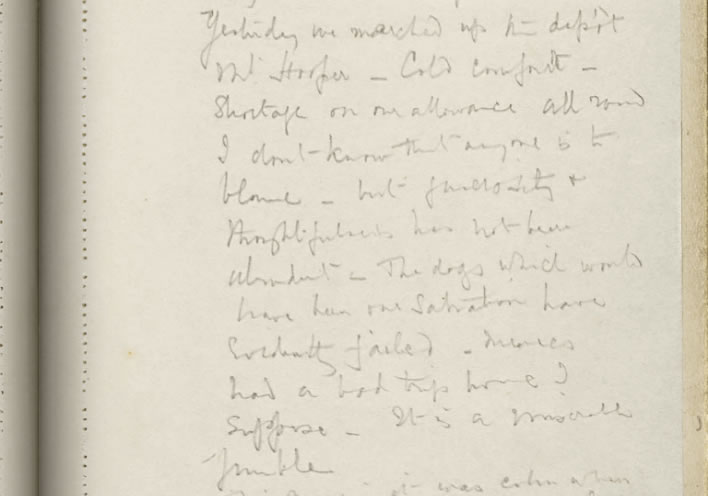

10.03

Cold comfort. Shortage on our allowance all round. I don't know that anyone is to blame , but generosity and thoughtfulness have not been abundant . The dogs which would have been our salvation have evidently failed . Meares had a bad trip home I suppose. It is a miserable jumble. |

| [Death march of polar party] |

11.03

We have 7 days' food and should be about 55 miles from One Ton Camp to-night, 6 × 7 = 42, leaving us 13 miles short of our distance, even if things get no worse. |

|

|

14.03

Must fight it out to the last biscuit, but can't reduce rations . |

||

| 16/17.03 [Oates walks out] No. 14 pony camp, only two pony marches from One Ton Depot |

||

|

18.03

We have the last half fill of oil in our primus and a very small quantity of spirit – this alone between us and thirst. |

||

| [Scott's tent. Scott was 39 days later than Evans.] |

19.03

We are 15½ miles from the depôt and ought to get there in three days. What progress! We have two days' food but barely a day's fuel . |

|

|

21.03

To-day forlorn hope, Wilson and Bowers going to depôt for fuel . |

||

| 22-23.03 no fuel and only one or two of food left |

||

|

29.03 ?

We had fuel to make two cups of tea apiece and bare food for two days on the 20th. [Scott, Wilson and Bowers are dead, 11 miles from One Ton Camp.] |

||

| One Ton |

09.02

[Lashly] A very fine day and quite warm. Reached the depôt at 5.5 P.M. and we all had a good feed of oatmeal. Oh, what a God-send to get a change of food! We have taken enough food for 9 days, which if we still keep up our present rate of progress it ought to take us in to Hut Point. We cannot take too heavy a load, as there is only the two of us pulling now, and this our last port of call before we reach Hut Point, but things are not looking any too favourable for us, as our leader is gradually getting lower every day. It is almost impossible for him to get along, and we are still 120 miles from Hut Point. |

03-10.03 [Cherry-Garrard's support party arrived on 03.03 (Scott had just left Mid Barrier depot), stocks up the depot and leaves on 10.03 (Scott had reached Mt. Hooper depot).] |

| Bluff | 13.02 | - |

| [Evans tent] |

18.02

[Crean leaves] Then Lashly came in to me, shut the tent door, and

made me a little porridge out of some oatmeal we got from the last depôt we had passed

.

[Lashly] After Crean left I left Mr. Evans and proceeded to Corner Camp which was about a mile away, to see if there was any provisions left there that would be of use to us. I found a little butter, a little cheese, and a little treacle that had been brought there for the ponies. I also went back to the motor and got a little more oil while the weather was fine. |

- |

| Hut Point | 19.02[Lashly] After Crean left I left Mr. Evans and proceeded to Corner Camp which was about a mile away, to see if there was any provisions left there that would be of use to us. I found a little butter, a little cheese, and a little treacle that had been brought there for the ponies. I also went back to the motor and got a little more oil while the weather was fine. | - |

Assessment of the timeline

From even a relatively superficial review of the timeline the following general points can be extracted:

- Apart from the 'short' biscuit box on 07.02 (see the discussion of this point later), all the food rations at the depots were in order and as foreseen– at no point does Scott say otherwise. Scott's team was short of food because of delays and the extra calorific requirement for strenuous sledge-hauling in extreme cold: 'we cannot afford to save food and pull as we are pulling'. [04.03] Even after the death of Edgar Evans on 17.02 meant that there was one less mouth to feed, the situation did not improve. Oates' death on 17.03 came too late to help.

- The critical shortage is fuel. From the South Barrier depot onwards the shortage of fuel becomes ever more desperate. We read repeatedly of Scott's party having more food available than fuel, meaning that the lack of fuel was almost always the limiting factor. It is assumed that the leather seals on the stoppers of the fuel cans leaked at low temperatures and allowed evaporation at high temperatures, which would explain the shortages. At no point does Scott suggest that insufficient fuel has been left behind by the other parties with access to the depots.

- From occasional remarks after the South Barrier depot (27.02, 17.03, 10.03) it is clear that Scott is hoping for the arrival of adog team. During most of this time Cherry-Garrard and a dog team were waiting at One Ton camp with no idea of what to do next.

- In a hare-brained and extremely risky action, Teddy Evans' team made a direct descent of the ice falls above the Beardmore glacier [13.02] to attain the Upper Glacier depot. This manoeuvre paid off, saving the team three days' march according to Evans. The estimate seems reasonable, since before the icefalls Scott's team had been 24 days behind Evans; by the next depot, Mid Glacier, it is 27 days behind.