13 December: Saint Lucy's Day

Richard Law, UTC 2017-12-11 08:53

Last year on Saint Lucy's day we looked at the celebration of her day as an astronomical phenomenon, the saint of light being herself as obscure as Saint Barbara.

This year our Lucy meditation comes from Johann Peter Hebel's (1760-1826) classic German story Unverhofftes Wiedersehen, 'The Unhoped-for Reunion', (1811) a short story that is highly regarded in the German-speaking world. Hover the cursor over the marked sections for brief annotations.

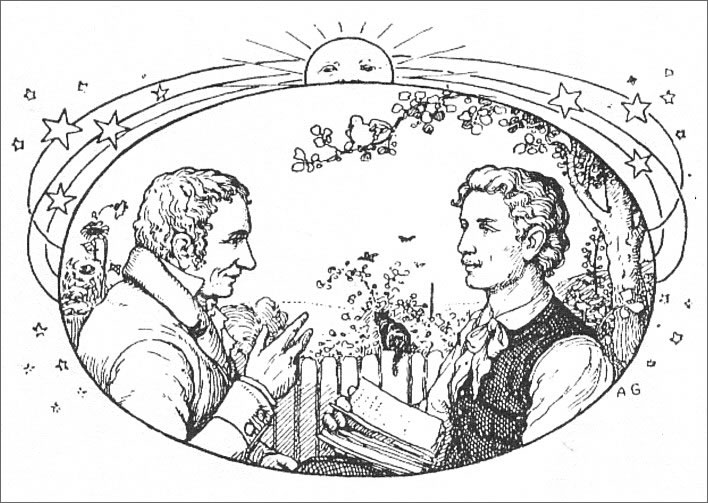

Watercolour portrait of Johann Peter Hebel and Elisabeth Baustlicher by Carl Joseph Alois Agricola (1779-1852), 1814, usually titled 'Hebel und Vreneli'. ('Vreneli' is a common regional name, the short form of Verena. It is here used as the generic name for woman from the area.)

The picture shows the 54 year-old Hebel – poet, writer, prelate in the Lutheran Church and teacher – in a characteristically schoolmasterish pose. The model for the girl was the 19 year-old Elisabeth Baustlicher from Langendenzlingen. She is wearing the traditional costume of the Markgräflerland, a region of southwest Germany between Basel in the south and Freiburg in the north. In the background of the picture is the Roman Catholic church of St. Stephan in Karlsruhe, then newly completed in 1814. Hebel had been the Director of the Gymnasium in Karlsruhe since 1808. He was a lifelong Lutheren Protestant, so we can assume that the striking design of the Catholic church was used by Agricola only as a locator.

This image was used as the starting point for the 80-Pfennig stamp produced by Elisabeth von Janota-Bzowski for the German Bundespost in 1985 to commemorate the 225th anniversary of Hebel's birth. For the purpose of the stamp the image was flipped horizontally and the background changed to a generic regional background (possibly Hausen, where Hebel grew up). The stamp design is reproduced as the menu thumbnail for this article. Image: Das Historische Museum Basel.

Johann Peter Hebel: The Unhoped-for Reunion, 1811

In Falun in Sweden fifty years and more ago a young miner kissed his pretty young bride and said to her: 'On Saint Lucy's Day our love will be blessed by the hand of the priest. Then we shall be man and wife and we shall build ourselves our own little nest.' – 'And peace and love shall live there', said the beautiful bride with a tender smile, 'because you are my only one and are everything for me, without you I would rather be in the grave than anywhere else.'

But before the priest could read the banns for the second time in the church before St Lucy's Day: 'If any of you know cause, or just impediment, why these two persons should not be joined together in holy Matrimony, ye are to declare it' – Death responded.

For when the next day the young man in his black miner's clothes passed her house – the miner always has his death clothes on – he tapped on her window and wished her a good morning – but he would never wish her a good evening, for he never returned from the mine. That same morning she sewed a red border onto a black neckerchief for him to wear on their wedding day, but, in vain. He never came, she laid it to one side, and wept for him and never forgot him.

Time went by. The city of Lisbon in Portugal was destroyed by an earthquake, the Seven Years' War came and went, Emperor Franz I died, the Jesuit Order was suppressed, Poland was partitioned, the Empress Maria Theresia died, Struensee was executed, America became free and the combined forces of the French and Spanish failed to conquer Gibraltar. The Turks besieged General Stein in the Veterani Cave in Hungary and the Emperor Joseph died, too. King Gustav of Sweden conquered Russian Finland, the French Revolution and the long war began and Emperor Leopold also went to his grave. Napoleon conquered Prussia and the English bombarded Copenhagen. The farmers sowed and reaped, the miller milled, the blacksmiths hammered and the miners dug for the metal veins in their underground workshop.

Sometime around St John's Day in 1809 the miners in Falun wanted to dig a connection between two galleries, a good five hundred feet beneath the surface. They dug out of the debris and the sulphuric acid the body of a young man, which was soaked through with iron sulphate, but otherwise not decomposed or changed – one could fully see his facial features and his age, as though he had died only an hour before, or had fallen asleep at work.

They brought him to the surface, but his father and mother, his friends and acquaintances were all long dead and so no one could identify the sleeping man or knew anything about what had befallen him – until the former betrothed of that miner arrived, the miner who had gone that day to his shift, never to return. Grey, wizened and on crutches she came there and recognised her bridegroom. She sank down on the beloved body, trembling more with joy than sorrow. Finally, after she had recovered from her overwhelming emotions, she said: 'He is my betrothed, whom I have mourned for fifty years and whom God has now allowed me to see before my own end. Eight days before the wedding he went below the earth and never came up again.'

Those all around were overcome with sorrow and tears when they saw the former bride now in frail old age and the bridegroom still in his youthful beauty and how in her breast after fifty years the flame of young love had been rekindled. But he did not open his mouth again to smile or his eyes to see. He was carried back by the miners to her room and laid out there. She was the only one to whom he now belonged and she had all rights to him until his grave was ready.

The next day, when the grave had been prepared in the churchyard and the miners came to collect him, she opened a small box, took out the black silk kerchief with the red border and laid it round him. She accompanied him in her Sunday clothes as though it were her wedding day, not the day of his funeral.

Then, when he was laid in his grave in the churchyard she said: 'Sleep well now one more day or ten in the cool marriage bed and don't get impatient. I have only a little more to do and will come soon and soon it will be day once more. – What the earth has once returned it will not keep for a second time', she said as she left and looked back one last time.

Translation ©FoS. from Johann Peter Hebel, Unverhofftes Wiedersehen in Schatzkästlein des rheinischen Hausfreundes (first published 1811). Also in Hebel, Johann Peter. Poetische Werke, München, 1961, p. 252—255. Online. A facsimile edition of the 1811 edition is available online from the University of Düsseldorf.

Language and translation

Hebel wrote his stories without any affectations of 'fine style'. He wrote them for popular consumption, by the young and the old, the maid, the farmer and the citizen. For many people, Hebel's almanac stories were the only printed works they ever saw or read. He would have preferred to write them in the Alemannic dialect of the people of southwest Germany, Alsace and Switzerland that he loved so much, but the almanacs for which he was writing circulated outside those regions, so standard – 'High' – German was used. Despite that, Hebel's German is infused with the simplicity of the sentence structures and the directness of expression that is characteristic of dialect speech. They are effectively oral tales, without any apparent literary decoration. Do not be misled by this apparent simplicity into thinking Hebel's writing is rough and ready: it isn't – it is very carefully crafted.

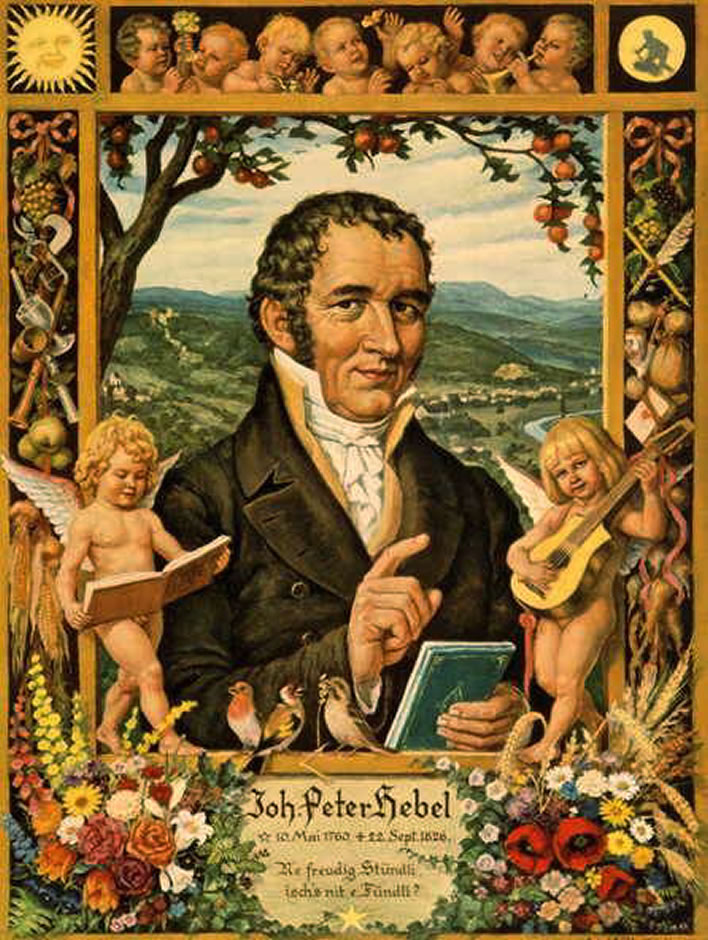

Johann Peter Hebel by Adolf Glattacker in 1910 (150th anniversary of Hebel's birth). The text on the banner is from the poem Freude in Ehren, 'Joy in respect' from Hebel's immensely successful book of dialect poems Alemannische Gedichte, 'Alemannic Poems' 1803-1820: 'Ne freudig Stündli, / isch's nit e Fündli? / Jez hemmer's und jez simmer do; [es chunnt e Zit, würd's anderst goh.] ', 'A joyful hour, isn't it a treasure? Now we have it and we are here; [a time will come when things are different.]' The background appears to be that of the Wiesental, where Hebel grew up.

This simplicity is a challenge for the translator. The oral stream-of-consciousness of some parts of the original is difficult to render without producing convoluted, clause-infested English. The translator has therefore allowed himself the occasional full stop.

A particular challenge in Unverhofftes Wiedersehen involves trying to keep the syndetic 'and…and…and' structure of the history section of the story. Hebel's use of this technique excites some literary commentators and its accurate rendering is therefore of some importance. However, a slavish imitation of the original would have led to a tedious read in modern English, where commas are quite sufficient. The overall syntax of the 'history review' has been kept, however.

The translation of the title Unverhofftes Wiedersehen as 'Unhoped-for Reunion' is quite deliberate, if slightly inelegant: words such a 'unexpected' or 'unforeseen' lack the emotional component of unverhofft– a longing for which the hope of attainment had been abandoned. If Hebel had meant 'unexpected' he would have written unerwartet or one of its synonyms. He didn't. He wrote unverhofft.

A title vignette by Adolf Glattacker for Hebel's book Schatzkästlein des rheinischen Hausfreundes, 'Treasure Box of the Rhineland House Friend'. We might think that Hebel is just being portrayed as usual as the pious explainer for the young – the teacher and clergyman. But more importantly, both Glattacker's image and Agricola's image above, 'Hebel und Vreneli', show us Hebel speaking directly to his readership: the literary style that made him so popular and loved in Germany down to the present day. In both the images, Hebel is not here in person, he is speaking in each case through the book held by the reader. Both images are clever metaphors of Hebel the writer.

Technique and style

Although written in a style accessible for a popular readership the story is not without its subtleties.

Teachers of creative writing will have already noted that the young miner and his love remain anonymous. Such anonymity is very characteristic of Hebel's writing: the great historical figures who appear in his stories (such as Napoleon) are of course named, but the common people, no matter how important they are in the plot, are generally left with generic titles – a farmer, a young women, a vicar etc. Hebel does not make up names for them. This anonymity allows the reader to identify more easily with the characters in the tales. It also avoids distracting the reader from the moral generality of the story.

In contrast, in designating places he is always remarkably specific. He can do this, of course, because he has anonymised the actors in his stories. He is, as the German literary critic Wilhelm Zentner noted, 'a friend of all factuality':

In his stories nothing ever happens in just any old inn, but in a Swan, or a Bear or a Red Ox, just as infrequently, too, in an unnamed town, but rather in Segringen, Brassenheim or Mauchen.

Wilhelm Zentner in Hebel, Johann Peter, and Wilhelm Zentner. Aus dem Schatzkästlein des rheinischen Hausfreundes, Reclam, 1994, p. 73.

Thus in Unverhofftes Wiedersehen we have the mines specifically in Falun, in Sweden. The precise naming of places also reinforces the regional focus of his work. His stories are from the 'Treasure Box of the Rhineland House Friend': the naming of places in that region allows his readers to identify strongly with the tales as a product of and for their own area.

There is a great deal of structure in the tale: for example, the miner dies around Saint Lucy's day, the shortest day of the year, and his body is recovered around Saint John's Day, the longest day of the year; the conclusion puts dead youthfulness and agèd love side by side; there are descents (down the mine, into the grave) and resurrections (into the day, then into 'the day'). The neckerchief is the physical symbol of the love that survives the half-century of separation; its ultimate purpose is achieved at his interment, representing the reunion of bride and groom, the wedding and the funeral.

The moral message

Hebel was writing stories that were both entertaining and had a moral message. The principal message here is the permanence of love and the permanence and superiority of the eternal life of the soul. Such eternal existence transcends not only the quotidian life but also the great events that mark the passage of human history. Even momentous events such as the Lisbon earthquake in 1755 are mere blips compared with the eternal life of the soul.

Hebel makes the idea of eternity, when 'it will be day once more', comprehensible to every reader – whether Vreneli reading on her walk or the young man reading in the garden – without the need for long philosophical excursions. The darkness of St Lucy's Day with its missed wedding has become the light of Saint John's Day with its 'unhoped-for reunion', just as the darkness of the earthly life will become the light of the eternal life to come. Hebel's readers are not required to understand the concept of eternity in all its complexity, but simply to experience it emotionally as the fixed rock of faith in the turbulence of human life and history, one that overcomes all disasters and mortal setbacks: 'it will be day once more'.

The half-century

Some commenters have read some significance into the selection of events in Hebel's history of that half-century, but this is stretching things too far – the only thing that all of these events have in common is that they were bad news involving disasters and death.

It is notable, for example, that we encounter the Habsburg emperors at their deaths not at their accessions: we do not read of Joseph II's accession, but of his father Franz I's death, his mother Maria Theresia's death, his own death and his brother Leopold II's death. The accession of Emperor Franz II/I in 1792 goes unmentioned – there was no death yet to report in 1811. He would outlive Hebel by nearly 10 years. The imperial deaths are the most obvious symbol of the mortal chains that bind prince and pauper in equal measure. From their imperial Midsummer they too proceed ultimately to their mortal December.

The historical events that Hebel lists are the major events that would stick in the minds of people who had lived through the period: the bad news is memorable. Hebel's list is not a careful, balanced historical review: these are the events that people would have heard about as children at the fireside, as adults in the tavern. They are the 'where were you when you heard about…' moments of the 18th century. The oddities in the list offer us moderns some interesting insights into the cultural constitution of the times, so perhaps a few words on them are in order.

For example, unless you are a Dane interested in history you have probably never heard of Johann Friedrich Struensee (1737-1772), a German who was executed on 28 April 1772 by the Danes for his intrigues at court. The death penalty came as a surprise to contemporary observers and the extreme barbarity of the execution – beheading, quartering and wrapping his limbs through the spokes of waggon wheels – revolted the enlightened minds of Europe. The manner of his end would still have been relatively fresh in the memories of Hebel's generation.

Another mystery for most modern readers will be Hebel's mention of the Austrian, General von Stein – at the time Major Stein – who made a name for himself in 1788 by his heroic defence of the Veterani Cave against the siege of the numerically overwhelming Turkish forces. The cave is in the side of the cliffs forming the 'Iron Gates', a gorge on the Danube between Serbia and Romania. It is now under the waters of a hydroelectric dam on the Danube.

The siege was ultimately successful for the Turks, who granted Stein and his men an honourable retreat in recognition of their brave resistance. The fame of this action lasted into the early years of the 19th century, but Joseph II's futile war with Russia against the Ottoman empire had been extremely unpopular amongst his people and its successes were quickly forgotten.

For us moderns, the memory of Stein and his exploit has sunk beneath the waves of Lethe just as surely as the Veterani Cave has sunk beneath the waters of the Danube, so the presence of Stein's name in Hebel's list nowadays leaves everyone but specialists in the period scratching their heads. But at least when Hebel was writing this story 20 years after that event Stein was obviously still remembered for his remarkable feat of arms. Perhaps those deeds would also be eclipsed for later generations by the great actions of the Napoleonic wars.

Adolf Glattacker revisited his 1910 commemorative panel, this time in 1926 for the 100th anniversary of Hebel's death. The text at the bottom of the panel consists of the first two lines of the previous quotation: ' Ne freudig Stündli, / isch's nit e Fündli?', 'A joyful hour, isn't it a treasure?'.

The factual background

The core of Hebel's story is based on a real-life event. It is a curiosity that adds nothing to our understanding or appreciation of Unverhofftes Wiedersehen, but is reproduced here for the curious in the account by Gotthilf Heinrich Schubert (1780-1860), a German doctor and philosopher. It is not certain that Hebel used Schubert's account specifically, but Hebel, the almanac writer with a deadline, would be constantly casting around for ideas which he could use for his purposes:

… the remarkable corpse described by Hülpher, Cronstedt and the Swedish journals, although apparently transformed into rigid stone had decomposed into a kind of ash after being stored in a glass cupboard, supposedly sealed from the access of air.

The former miner was found in the Swedish iron mine at Falun whilst the miners were attempting to cut a passage between two shafts. The body, completely soaked in green vitriol, was initially soft, but as soon as it was brought out into the air became hard as rock.

The body had lain 500 feet underground in that vitriol solution for fifty years. No one would have recognised the unchanged facial features of the young man nor the time he had lain there - the mine records and the memories of the people were uncertain given the number of accidents there had been - had it not been for the fact that an old true love remembered those features.

For as the people were looking at the unknown youthful features just after the recovery of the body to the surface, an old lady with grey hair and on crutches sank with tears in her eyes over the body of the beloved dead one, who was once betrothed to her, blessing the hour that she, at death's door, had been granted such a reunion. The people watching saw with amazement the reunion of this strange pair, one of them in death and the deep crypt in which he had lain had kept his youthful looks, the other, despite the withering and ageing of the body had kept its youthful love true and unchanged and how, for their 50-year silver wedding anniversary the still young groom was stiff and cold and the old and grey bride was full of warm love.

Translation ©FoS. from Schubert, Gotthilf Heinrich. Ansichten von der Nachtseite der Naturwissenschaft, Dresden, 1808, p. 215f. Available online at DTA Deutsches Textarchiv.

Schubert's account and other sources for the historical basis of Hebel's story have been investigated by Carl Pietzcker, according to whom the real-life discovery of the young man's body took place in 1719.[1] However, the ending of the historical account has nothing in common with Hebel's story. The old lady sold her bridegroom's corpse to the Medicine Faculty at the University of Uppsala for 500 Taler – a substantial sum that would have been very welcome in her old age. Hard-bitten empiricists will regard the cash windfall that her bridgroom brought her as being better than any graveside speech.

In Uppsala, just as Schubert tells us, the corpse was stored under glass, where it decomposed, finally being buried in 1749. Unlike the conclusion of Schubert's account, the 'warm love' he reports seems to have come into contact with cold monetary reality.

The critical reception of Unverhofftes Wiedersehen

The Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch (1885-1977), whose judgement on all the great issues of the age – such as that boon to mankind, Joseph Stalin – was seriously flawed, was, however, a widely read and perceptive literary critic. In the afterword to his selection of Hebel's Kalendergeschichten, among them Unverhofftes Wiedersehen, he asserted that the latter was 'the most beautiful story in the world'.[2]

Another Marxist dreamer, the German philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892-1940), mentioned Unverhofftes Wiedersehen for its integration of the passing of history into narrative structure, but said nothing of interest about the story itself. (Benjamin fans might disagree with that statement.)[3]

Hebel's parental house in Hausen, Wiesental. Engraving by R. Dawson. Image: ©Landesmedienzentrum Baden-Württemberg.

More interestingly, Wolfdietrich Schnurre (1920-1989), himself a renowned German writer, cheers us up with his idiosyncratic autobiography Der Schattenfotograf, 'The Shadow-Photographer' (1978). We used an anecdote of his from the same book for our 'Quote of the Month' in September this year. He chose Unverhofftes Wiedersehen, 'the most beautiful story in the world', as the text to be read at his funeral:

I imagine it like this. The coffin from fresh pinewood. No finish, merely planed. People should be able to smell me on my way to the grave. The grave, wherever it can be located – but in Berlin, of course. The headstone uncarved. Granite. Initials will be sufficient. Under no circumstances should anyone get the impression that the stone has been erected. Left to themselves, stones do not stand up vertically. My headstone should lie flat. Exactly over my head. Because of the correspondence between the two. Planting: ivy, causing no one any maintenance effort.

At the graveside no sermon, no music. But someone with a good voice should read the most beautiful story in the world at the open grave. It is not long, about two and a half pages. It is called Unverhofftes Wiedersehen and was written by Johann Peter Hebel. When the reading is finished, there should be a clear announcement by the open grave of the whereabouts of the restaurant or the pub where the funeral wake is going to be held.

Wolfdietrich Schnurre, Der Schattenfotograf. Aufzeichnungen 1920-1989, München, List Verlag, 1978, p. 522. Translation ©FoS.

The best short summary of the exemplary qualities of Hebel's story that I know comes from the German literary critic, Norbert Oellers:

The story Unverhofftes Wiedersehen is generally considered to be the most valuable jewel in the Schatzkästlein, the 'Treasure Box'… [It] belongs in language and composition to the consumate masterpieces of storytelling… A death decays with time as does every other event, but time loses its power when it is 'day once more'. The more turbulently time flows, the stronger is the hope for the preservative power of eternity.

A lot happened in those 50 years… The way Hebel reviews for the reader a half-century of world history in just a few sentences, the way he retrieves the past and links it to the present, the way he uses repetition as a bridge between then and now, extending beyond the time recounted and yet without losing sight of the purpose of the narrative: the abolition of all time, even the repeated present. That achievement is in content and form without equal.

In 1810 Goethe read Unverhofftes Wiedersehen aloud to a social gathering and everyone cried. He said: 'It is the leading story in all the forty-two anthologies which have appeared in this book fair.'

Oellers, Norbert. 'Johann Peter Hebel' in Wiese, Benno von, editor. Deutsche Dichter Der Romantik: Ihr Leben Und Werk; Unter Mitarbeit Zahlreicher Fachgelehrter Herausgegeben von Benno von Wiese. 2., Überarbeitete und verm. Aufl, E. Schmidt, 1983, p. 81.

I hope that you, in the darkness of Saint Lucy's Day, with the certain hope of the waxing of the days towards the great light of Saint John's Day, agree with Goethe, Schnurre, Oellers and the rest.

Johann Peter Hebel, etching by Franz Müller c.1820. Image: ©Landesmedienzentrum Baden-Württemberg.

References

- ^ Pietzcker, Carl. 'Nachgeholter Abschied: Johann Peter Hebels »Unverhofftes Wiedersehen«' in Freiburger literaturpsychologische Gespräche Band 13, Würzburg, 1994, pp. 139-162, p. 147.

- ^ Bloch, Ernst. 'Nachwort zu Hebels Schatzkästlein' in Literarische Aufsätze. Gesamtausgabe Band 9, Frankfurt am Main, 1965, p. 175.

- ^ Benjamin, Walter. Der Erzähler. Betrachtungen zum Werk Nikolai Lesskows, in Gesammelte Schriften, Band II, 2, Frankfurt am Main, 1977, p. 438-465, p. 450.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!