A Christmas Carol

revisited

Richard Law, UTC 2017-12-24 11:15 Updated on UTC 2023-06-27

'Tis the season for Charles Dickens' (1812-1870) deservedly popular tale of the time-travels of Ebenezer Scrooge, A Christmas Carol (1843).

As everyone knows, Ebenezer's transformation from hard-bitten, misanthropic grump to cheerful friend of the poor is effected through the agency of three spirits: the Ghost of Christmas Past, the Ghost of Christmas Present and the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. It's a good tale well told, which carries us along with an effortless suspension of disbelief.

Calling it simply a seasonal standard would be an insult, because in the 180 or so years since it was written the story has done more than anything else to define the 'season of goodwill' itself, or at least its non-commercial aspects. Everyone knows what a Scrooge is, and, like the original Scrooge, we are all expected to purge ourselves of our baser nature for this season of goodwill.

The work is deeply rooted in the Christian moral revival of the nineteenth century, one of the great aims of which was to bring charitable compassion to the great social revolution of the day: the mass migration of people from rural villages to the teeming cities that fuelled the factory labour of the Industrial Revolution. The rural poor migrated to become the urban poor, the main difference between them being that the concentration of the destitute and downtrodden made them much more visible to the better off.

Britain led the way in that revolution and led the way in its consequences, too. The roots of the two centuries of economic growth and social advancement which followed that revolution fed on its malodorous, heaving human loam. Count your blessings: after that ascent to the light we moderns are now living in times in which we fret that too many people are too fat or not bothering to work for a living or the waiting time for hip replacements is too long.

The moral tone of A Christmas Carol is religious, but without religion: there is no mention of God or even the Saviour born in Bethlehem. Theology has been entirely filleted out of the work, leaving a Christmas without Christ. No vicar or evangelical takes Scrooge in hand. He is reformed not through fear of Hell's eternal torments or any wish to be 'saved', but through an appeal to his humanity by showing him the wider consequences of the life he is living.

The story's message is essentially 'be kind'; it is a message filled with hope, and the assumption that people – even monsters like Scrooge – in their deeper, empathetic natures just want to be good. In short, it's a Christmas message even an atheist can get behind, one for an increasingly atheistic age.

The iconic status of the work has left a broadbrush understanding of it in contemporary culture. This is a pity, because it masks the clever subtleties in the work's conception. Let me illustrate a few of these by looking at just one theme: the 'time travel' of the journeys to the three Christmases.

Shadows and shades

It is striking that Dickens avoids all physical interactions between Scrooge and the three different times he visits. Scrooge and his various ghostly guides observe and listen, but never intervene in these worlds.

'These are but shadows of the things that have been,' said the Ghost. 'They have no consciousness of us.'

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol, Chapman and Hall, London, 1843. online, p. 24.

What Dickens has done here is quite remarkable, for he has inverted the dominant tradition of ghost stories – that ghosts can pass through the solid objects of our human world – to the novel demands of his narrative, in which he shows us, in effect, those now immaterial worlds through the eyes of the ghost. Scrooge himself becomes a ghost in order to be taken, unseen, ghost-like, to the shadows of these other times and places.

The Ghost of Christmas Past (Amelia Bullmore) and Scrooge (Jim Broadbent) in a 2015 UK production of A Christmas Carol. Image: ©Johan Persson.

The spirit manifestations in A Christmas Carol are much more subtle than the ghosts and ghouls then in fashion among Dickens' contemporaries. Scrooge's ghostly guides may appear before him in the present in the traditional manner of ghostly manifestations, but their dealings with him require an additional mechanism: the solidly real Scrooge and his spirit guides travel to, observe and pass through the 'shadows' of these other worlds without hindrance – an additional layer of ghostly manifestation in other words, apparitions within apparitions. Could all this be merely a dream? It doesn't feel like it. These shadow worlds are the otherwise unreachable places where the past, present and the potential future are to be found.

A light shone from the window of a hut, and swiftly they advanced towards it. Passing through the wall of mud and stone, they found a cheerful company assembled round a glowing fire.

Dickens p. 102.

As at many other places in the work, Dickens' startling narrative and strong imagery sweeps us along unhindered by much reflection. But these two simple sentences repay examination, for they demonstrate that the scenes presented to Scrooge are not simply visions or trances conjured up in Scrooge's mind: they are physical – if insubstantial – places to which one journeys – towards a light, through a wall and into a room with people. The past and the present at least are landscapes through which we can move; these shadow worlds are places to which one goes and as such they have a topography as evident as a walk down a real street.

Journeying back in time

The intellectual subtlety of Dickens' handling of the journeys of Scrooge and his ghostly guides into other times and places, particularly in the explicit non-intervention of the observers in these other worlds, means that the tale avoids getting tangled up in the 'time-travel paradox'.

In the popular form of the paradox we realise that an assassination of a young Hitler or Stalin, say, would break the causal chain reaching into the present and make the present an impossibility. It would also make the return of the time-travelling observer impossible and call into question the observer's very existence, whether in the past or the present. We cannot get round this, even with all the modern speculation about alternative universes.

This paradox never occurred to H. G. Wells, the writer with a science background, in his iconic novel The Time Machine. The tale violates the paradox at every turn, not just through the Time Traveller's escapades in past times, but also most notably with a flower brought back from the past to the present. There is even a visit to the distant future of a dying planet Earth. Wells clearly didn't think this through, but the nonsense of the novel has not stopped its enduring popularity. Suspension of disbelief, indeed.

But such violations represent simply the most obvious manifestation of the time-travel paradox – other difficulties are much more profound. For example, the fastidious modern physicist would read A Christmas Carol and wonder how Scrooge could even see or hear his visions of the past without having some quantum electrodynamic impact on their worlds, since to see and hear these happenings requires some energy transfer – and who knows what the result of that tiny perturbation might be: butterflies flapping their wings and all that.

For even if a time traveller did not disturb what we might call the macroscopic structure of this past world – that is, the big objects within it such as Adolf Hitler – any change of its microscopic structure would also break the causal chain linking the past to the present. The positions and the states of every atom or even every subatomic particle, every photon even, would have to remain unaffected by the presence of this observer from the present. Whether the intruder in this past world was a human observer or an inanimate object such as a camera, the quantum electrodynamic interactions caused by his, her or its presence alone would break the causal chain to the present.

Dickens, writing a century before our modern quantum electrodynamical understanding of the material world, cannot be expected to anticipate all these difficulties. Nevertheless, it is remarkable how astutely he introduces the mechanism of a supernatural journey with its immaterial 'shadows' through which one can pass to create at least a primitive barrier of interaction between the observers and the observed, allowing him largely to avoid the problem of the time-travel paradox.

Future conditional

We would also expect to have a problem with Scrooge's visit to the future, but with a different restriction, since whatever Scrooge saw in 'the future' would be an absolute predestination. A predestined future is an absurdity: not only would it remove all trace of free will from human actions, but it would allow no possibility of Scrooge's reform.

We have already remarked on the landscape character of the past and present through which Scrooge and the respective spirits journey. Despite its conditionality, the future also has a landscape, and a very pronounced one at that: 'The Ghost [of Christmas Yet to Come] conducted him through several streets familiar to his feet' [p. 141]. Dickens chose to maintain the conceit of the journey, which gave him so much scope for colour and narrative detail.

Dickens has clearly thought this through, since the visions of the future which Scrooge sees are only conditional states, projections of what might be if he doesn't change his ways. 'Why show me this, if I am past all hope?', Scrooge asks the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come at one point. This conditionality is so important in the novel that it had already been explained to Scrooge by the Ghost of Christmas Present:

'I see a vacant seat,' replied the Ghost, 'in the poor chimney corner, and a crutch without an owner, carefully preserved. If these shadows remain unaltered by the Future, the child will die.' 'No, no,' said Scrooge. 'Oh no, kind Spirit! say he will be spared.'

Dickens p. 96.

The Ghost of Christmas Present makes very explicit the prospect of redemption available to Scrooge – and all other humans – if genuine remorse drives them to mend their ways. The Ghost stokes up the miserable Scrooge's remorse by quoting his own vicious words back at him:

'If these shadows remain unaltered by the Future, none other of my race,' returned the Ghost, 'will find him here. What then? If he be like to die, he had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.'

Scrooge hung his head to hear his own words quoted by the Spirit, and was overcome with penitence and grief.

'Man,' said the Ghost, 'if man you be in heart, not adamant, forbear that wicked cant until you have discovered What the surplus is, and Where it is. Will you decide what men shall live, what men shall die? It may be, that in the sight of Heaven, you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man's child. Oh God! to hear the Insect on the leaf pronouncing on the too much life among his hungry brothers in the dust!'

Dickens p. 96-97.

In A Christmas Carol, as in mainstream Christianity, the predicate for future salvation is genuine remorse. The work does not speak of salvation at all, but simply of future – what may happen to Scrooge's soul in the life to come is of no interest to us, whereas the improvement in his future conduct is what matters. Without reform his life will lead inevitably to the general pleasure at the news of his death, to the robbed and abandoned corpse, to the untended gravestone in a neglected cemetery. For the Christian moralists of the time the good deed was what mattered, not a few points more on a salvation score card.

That Dickens has thought through the subtle logic behind his tale is shown by his hint at the nature of the spirits which visit Scrooge: 'If these shadows remain unaltered by the Future, none other of my race … will find him here.' From this remark we infer that each of the three spirits has its own field of independent action – past, present and future – and that each field has its own 'race' of spirits: 'none other of my race' – that is, the race of the spirits of the present – 'will find him here', when the future has become the present.

The future may be conditional, but the result of that condition is decided beyond alteration when it enters the present. Unlike the fashionable ghostly manifestations in some other writers of the period, Dickens has taken the trouble to ground his fantastical narrative into a superficially rational system.

The Ghost of Christmas Present does not allow Scrooge to avoid his fate with a few expressions of momentary regret but pounds him with painful sarcasm into a state of true remorse. At the conclusion of its encounter with the now wretched Scrooge, the Ghost reveals to him two abject children, 'yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish' and describes the terrible conditions in which they live.

'Have they no refuge or resource?' cried Scrooge.

'Are there no prisons?' said the Spirit, turning on him for the last time with his own words. 'Are there no workhouses?'

Dickens p. 120.

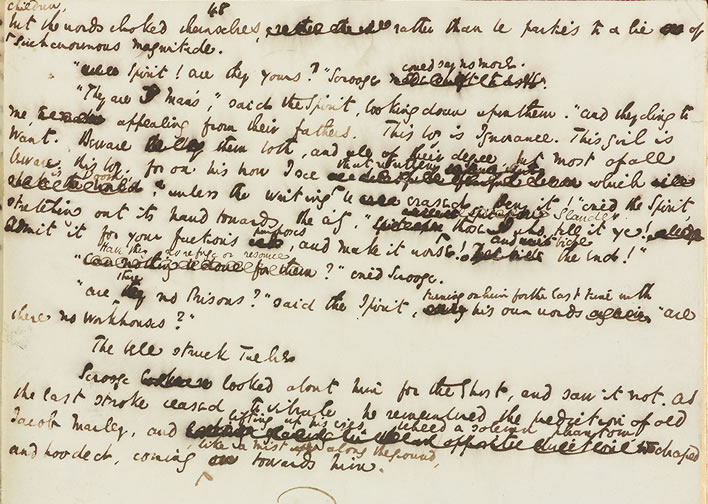

Great writer at work: image of a page of Dickens' autograph manuscript for A Christmas Carol, December 1843. Note, for example, after a first, then a second thought ('using'?), Dickens arrives as the final, much more powerful formulation for the damning utterance of the Ghost: 'turning on him for the last time with his own words'. Image: The Morgan Library and Museum, MA 97, Page 48.

By the time the Ghost of Christmas Present is finished with him Scrooge has been emotionally crushed. Now, when the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come appears, he is truly desperate to redeem himself.

Unlike its predecessors, this Ghost never speaks. Scrooge has many questions for the Ghost, but must speak out the answers himself – yet another stroke of genius by Dickens, in that it demonstrates in Scrooge's own words how completely he has understood the lesson the Ghosts have taught him and how genuine his remorse and desire to change his ways is. In our age we would say: 'He gets it'.

'You are about to show me shadows of the things that have not happened, but will happen in the time before us,' Scrooge pursued. 'Is that so, Spirit?'

Dickens p. 122.

'Are these the shadows of the things that Will be, or are they shadows of the things that May be, only?'

[…]

'Men's courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead,' said Scrooge. 'But if the courses be departed from, the ends will change. Say it is thus with what you show me!'

[…]

'Spirit!' he cried, tight clutching at its robe, 'hear me! I am not the man I was. I will not be the man I must have been but for this intercourse. Why show me this, if I am past all hope?' For the first time the hand appeared to shake.

'Good Spirit,' he pursued, as down upon the ground he fell before it: 'Your nature intercedes for me, and pities me. Assure me that I yet may change these shadows you have shown me, by an altered life!'

The kind hand trembled

'I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach. Oh, tell me I may sponge away the writing on this stone!'

Dickens p. 149f.

The narrative of the work describes the reforming effect that the insights given to Scrooge by the three spirits had on him. The work itself, however, has had a similar effect on generations of its readers. Dickens' friend Lord Jeffrey (1773-1850) famously wrote to him that A Christmas Carol 'had done more good than all the pulpits in Christendom'.

Our easy familiarity with A Christmas Carol causes us to overlook just what an astonishing intellectual performance it represents. It is a masterpiece that can stand comparison with any of Dickens' other masterpieces.

Update 27.06.2023

When I first wrote this piece on A Christmas Carol it led into a cumbrous and unreadably long disquisition on the nature of time. Revisiting the article nearly six years later I was embarrassed to discover what a tedious shambles it was.

I have now freed my remarks on Dickens' work from the clanking shackles I draped upon it – I hope readers find it interesting and digestible. Some of the other parts of the original article still have value, but will be recast and rewritten to remove some nonsense and improve readability. They will appear in time (pun intended)…

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!