21 February 1818, midnight.

Richard Law, UTC 2018-02-21 00:01

Two hundred years ago today, at midnight on Saturday 21 February 1818, Franz Schubert wrote:

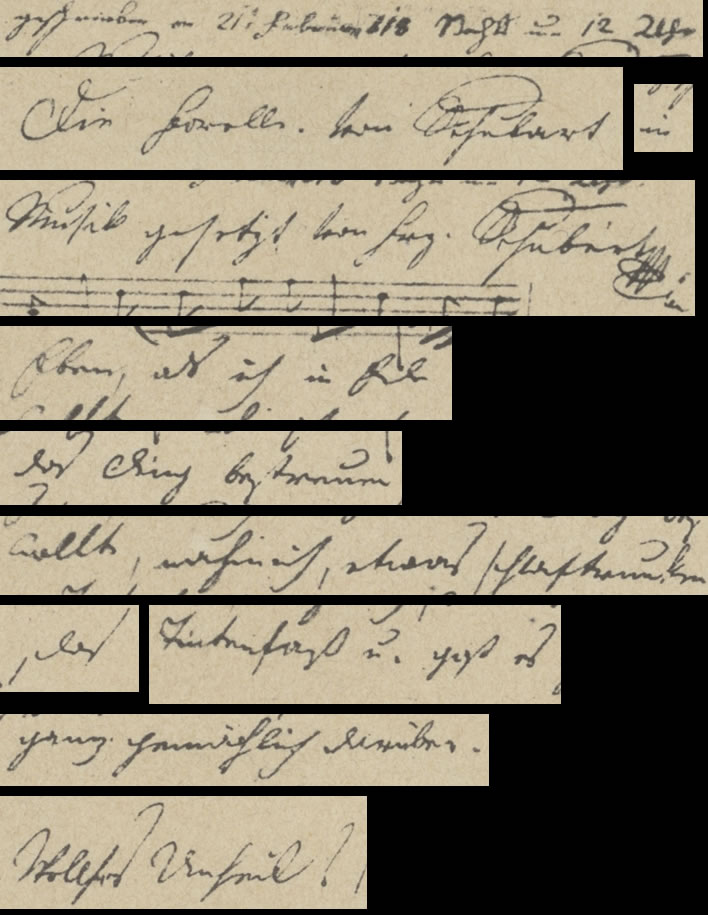

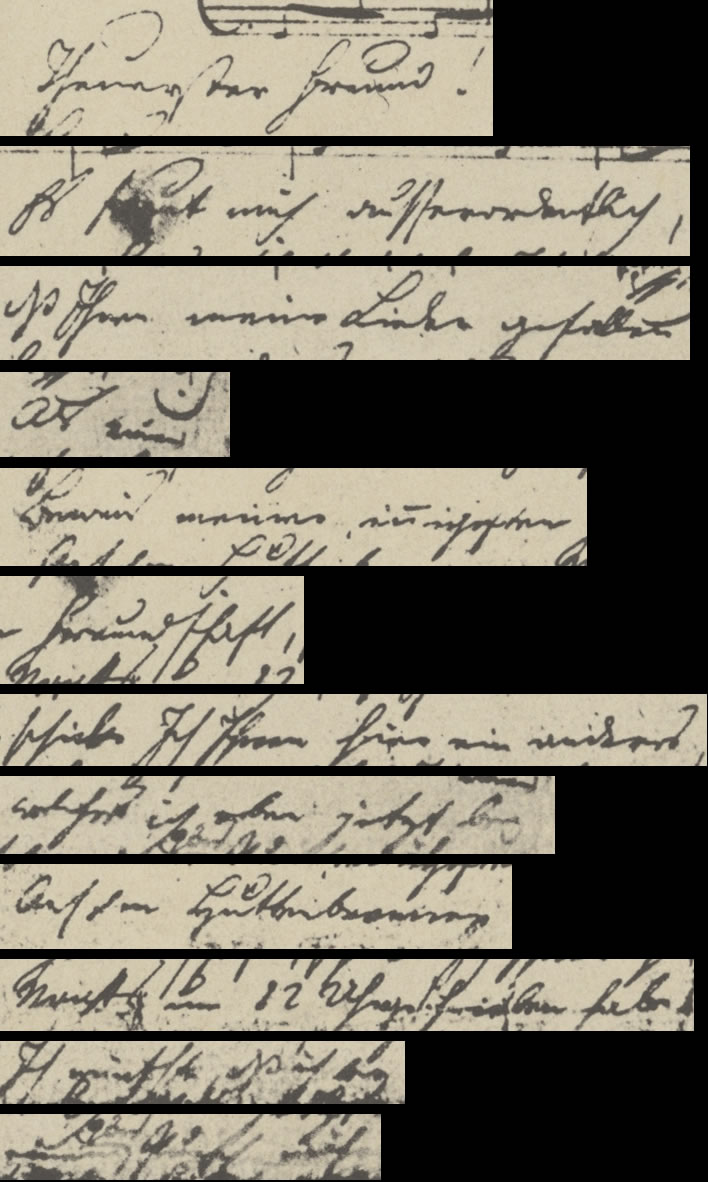

Written 21 February 1818 at 12 o'clock at night

The Trout by Schubart set to music by Franz Schubert mpia*.

Dearest Friend! It makes me extraordinarily happy that you like my songs. As a proof of my most sincere friendship, I am sending you another one, which I have written just now in Anselm Hüttenbrenner's room at midnight. I hope to get to know you better over a glass of punch. Farewell.

Just now, slightly drunk with sleep, I was wanting to sprinkle sand on the thing but in my haste I took the inkpot and poured it generously over it. What a calamity!

* mpia = manu propria = in [my] own hand.

geschrieben am 21. Februar 818 Nachts um 12 Uhr.

Die Forelle. Von Schubart ins Musik gesetzt von Franz Schubert mpia

Theuerster Freund! Es freut mich ausserordentlich, dß Ihnen meine Lieder gefallen. Als einen Beweis meiner innigsten Freundschaft, schicke ich Ihnen hier ein anderes, welches ich eben jetzt bey Anselm Hüttenbrenner Nachts um 12 Uhr geschrieben habe. Ich wünsche, dß ich bei einem Glas Punsch nähere Freundschaft mit Ihnen schließen könnte. Vale.

Eben als ich in Eile das Ding bestreuen wollte, nahm ich, etwas schlaftrunken, das Tintenfaß und goß es ganz gemächlich darüber. Welches Unheil!

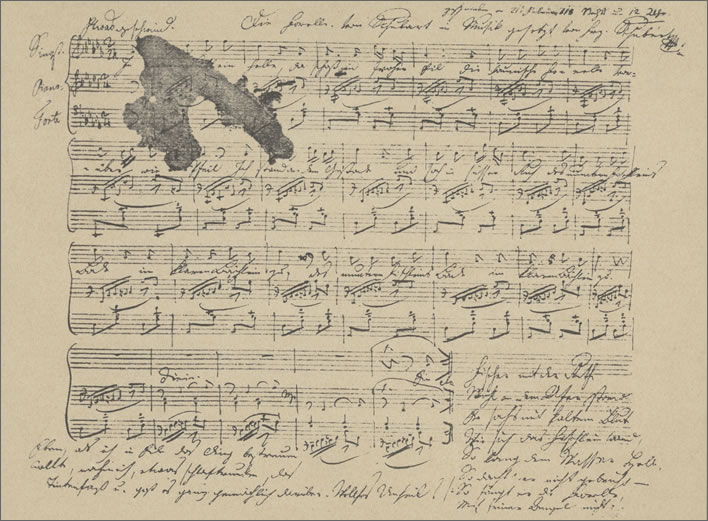

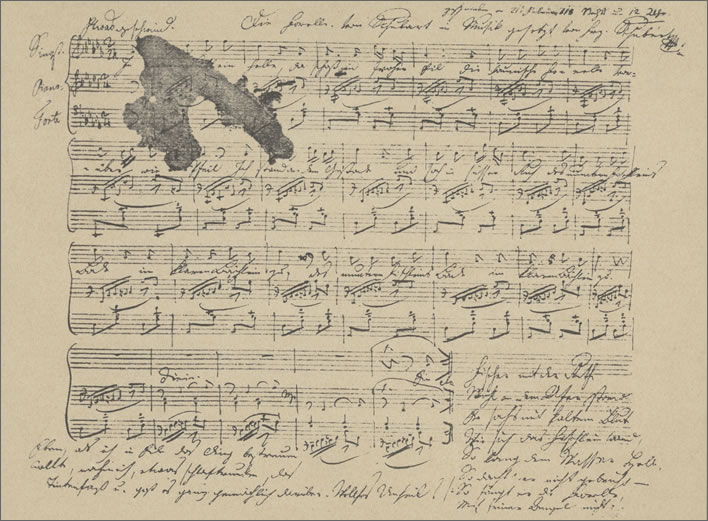

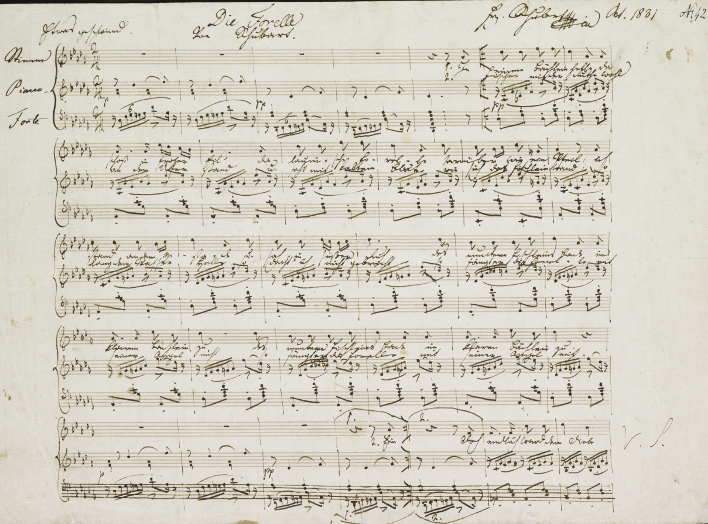

We don't have the original of this autograph: it is 'lost' – usually an Austrian archival euphemism for 'stolen' or 'hidden'. Fortunately, a photographic facsimile of the 'inkblot' score was made in 1881, before the original disappeared:

The first page of the facsimile of the inkblot autograph of Die Forelle, containing the first two verses of the song, the alien date, the title and Schubert's explanation for the inkblot. Image: ©Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Musiksammlung. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab (2176 x 1601 px).]

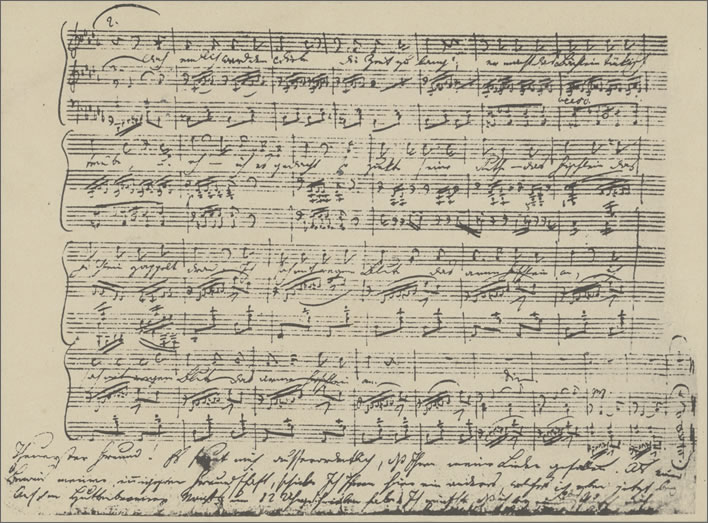

The second page of the facsimile of the inkblot autograph of Die Forelle, containing the last verse of the song and Schubert's extended greeting for Joseph Hüttenbrenner. Image: ©Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Musiksammlung. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab (2176 x 1606 px).]

Schubert wrote his note on an autograph score of his song Die Forelle (D 550). We looked at the complex background of this song in some depth here around two years ago.

On that evening of 21 February 1818 Schubert had written down the score and added the note we transcribed at the beginning of this article. The recipient is not explicitly named, but it is generally assumed that the autograph was to be sent to Joseph Hüttenbrenner (1796-1873), who was at that time on the family estate in his home town of Graz.

The 'Anselm Hüttenbrenner' (1794-1868) mentioned in the note was Joseph's brother and Schubert's friend, whom he first met when they were both pupils of Antonio Salieri. Anselm was one of the few musicians in Schubert's inner circle. In 1818 Anselm was studying in Vienna and the score and the note were written in Anselm's rooms above Josef Geistinger's bookshop (then Kohlmarkt 6, now Wallnerstraße 2 and completely rebuilt. The location is sometimes given as Neubad). [Erinn 58]

Happy days. Johann Baptist Jenger (1793-1856), Anselm Huttenbrenner (1794-1868) and Franz Schubert (1797-1828). Pastel by Josef Teltscher (1801–1837), 1827 (the year before Schubert's death). Original now – of course – 'lost'.

Understanding the message

According to Anselm Hüttenbrenner, he and Schubert had spent that evening drinking. The befuddled state of Schubert's message certainly lends credibility to Anselm's statement.

Schubert addressing Joseph as 'Dearest Friend!' was the wine speaking, since at that time he had only met Joseph briefly in person the previous summer, when Joseph was visiting Vienna. [Erinn 85]

For the same reason, the 'proof of my most sincere friendship' also sounds rather odd under the circumstances. Despite the fulsome words of friendship, Schubert addresses his friend in the polite Sie form (Ihnen, 3x). It is one of the curious facts of Schubert's biography that after he finally got to know Joseph in person, he appears to have stuck with the Sie form of address throughout their relationship.

The friendships that Schubert made in his childhood or in the Stadtkonvikt would generally always have used the du form of address. The choice between Sie and du only had to be made in the case of latecomers to the Schubert circles – such as Joseph Hüttenbrenner.

It may be that 'get to know you better over a glass of punch' subconsciously offers a future transition to du and thus to the Schubert inner circle – a transition which was never fully realised.

The note presents us with puzzle upon puzzle: Why was Joseph Hüttenbrenner, the recipient, not mentioned by name? Why was the location specifed so stiffly as 'Anselm Hüttenbrenner's room' and not, for example, 'your brother's room' or 'Anselm's room'?

Taking only those two facts together we might even begin to wonder whether this note really was written for Joseph Hüttenbrenner. And if it was intended for him, why was it in Anselm's possession in the 1850s? Joseph claimed that his brother Anselm had sent it to him on the family estate. This is not an unsurmountable problem, since by the 1850s, as shown in the case of the Unfinished Symphony, at least some of the music manuscripts the pair had collected had wandered into the care of Anselm. [Erinn 85]

That remark, 'get to know you better', after all this friendship and sincerity, throws the oddity of the effusive beginning in sharp relief: Schubert was somewhere between tipsy and drunk – of that there can be no doubt.

The musical mind at work

Despite all these indications of Schubert's alcohol degraded faculties we have to recognise how accurate his rendering of the score of Die Forelle was. There are no errors: Schubert has created not an exact reproduction of the original score but a very slight variant. We might even get the impression that Schubert's 'musical mind' was operating on a different level to his 'language mind'.

Those familiar with Schubert's autograph scores will immediately think of their written perfection. The greatest contemporary contrast is with Beethoven, whose later autograph scores are barely-legible battlefields. Compared to that, Schubert's scores are clean and almost print-ready, however scrappy the scrap of paper they were written on – they came out of his musical mind almost fully worked out.

One reason for this may be that during the early part of his life Schubert was usually living on whatever tiny allowance his father gave him. For his scores he usually had to rule the staves himself, unless some kind friend presented him with some pre-ruled music paper – as happened in the Stadkonvikt with Joseph Spaun. Whichever way he came by it, music paper was a valuable commodity which was never wasted on musical doodles. It seems that he learned to do the doodling in his musical mind before committing his creations to paper.

Such concentration of his musical mind led some of his contemporaries – Michael Vogl led the charge here – to talk of Schubert writing in a 'trance', as though he were just the radio receiver tuned to some muse's transmitter. Absurd. The explanation is really much simpler, as we see from the present case: Schubert simply didn't need to write things down as memory aids. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau somewhere noted Schubert's remarkable capacity for 'concentration' and 'intensification' in the composition of his music that demanded the equivalent from its performers.

Peter Härtling, in his novel Schubert, draws his reader's attention to the noisy environment in which Schubert lived: his earliest years in the cacophony of the family schoolhouse in a Viennese Vorstadt, where every other house contained artisans hammering away, the streets filled with the calls of hawkers and the noise of traffic; then his eight years in the cacophony of the Stadtkonvikt amid the bustle of a metropolis bursting at the seams; then his years writing his songs whilst supervising his school classes; and then his later years, nearly all of them spent in shared accommodation.

It is fair to say that Schubert would never have developed as a composer without his ability to concentrate, focus and operate in the compartment of his musical mind. We really shouldn't be surprised, therefore, that, when tired and tipsy after a boozy evening, he can recall a piece of music of the complexity of Die Forelle out of that wonderful musical mind and commit it faultlessly to paper. We busy paddlers know when we are in the presence of a swan.

The alien date

At the risk of ruining the second centenary of this charming, human moment entirely we have to confess that the date on the manuscript is not in Schubert's hand.

We know that Joseph Hüttenbrenner, during his few years as Schubert's amanuensis, was a happy modifier of Schubert documents, even forging Schubert's signature when necessary. But that said, although the date was not written by Schubert himself, we have no reason to believe that it is not accurate – there is no obvious advantage to be gained from this date or any another.

But we must be clear: whenever this date is mentioned in other documents it is never an independent corroboration, since that date always derives from the alien date on the Schubert's autograph.

Anselm, the possessor of the manuscript, quotes Schubert's note and the alien date to Luib [Erinn 77], then Luib repeats the alien date to Joseph [Erinn 85], then Joseph, writing to Luib, repeats the alien date in a wild misquotation of Schubert's note [Erinn 90] and finally Anselm, writing to Liszt, quotes the note and the alien date on the manuscript [Erinn 208]. In other words, the alien date on the manuscript is always the ultimate source for this date.

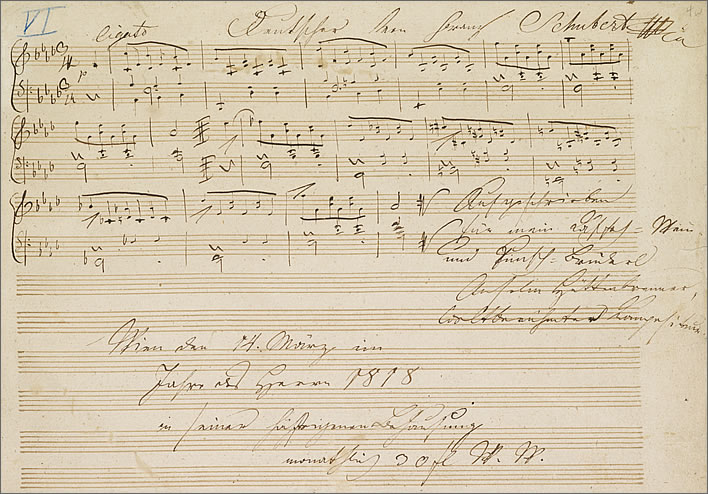

Another score, another message

We can see how odd Schubert's note on the manuscript score of Die Forelle is when we compare it with another non-dedication he added to a score he wrote down for Anselm the following month. Anselm recounted the story to Liszt:

For a long time the well-known, gentle Trauerwalzer in A-flat major [now D 365] was held to be a composition of Beethoven's, who, when asked, denied being its author. I found out by accident that Schubert had composed this waltz and asked him to write it down on paper for me, because so many differing copies were in existence. He did me the favour straight away and wrote in the margin of the score: 'Written for my coffee-, wine- and punch-brother Anselm Hüttenbrenner, composer. Vienna, 14 March in the year of Our Lord 1818 in his very own hutch (apartment) monthly 30 florins Wiener Währung'. — I was living at the time in the property of the bookseller Geistinger in the Kohlmarkt, where Schubert often visited me and stayed overnight several times.

Der bekannte gemütliche Trauerwalzer in As-Dur galt längere Zeit für eine Komposition von Beethoven, welcher, darüber befragt, die Autorschaft ablehnte. Zufällig erfuhr ich, daß Schubert diesen Walzer verfaßt habe, und bat ihn, denselben für mich zu Papier zu bringen, weil so viele voneinander abweichende Abschriften hiervon existierten. Er tat mir alsbald den Gefallen und schrieb am Rande des Notenblattes hinzu: »Aufgeschrieben für mein Kaffeh-, Wein- und Punsch-Brüderl Anselm Hüttenbrenner, Compositeur. Wien, den 14. März im Jahre des Herrn 1818 in seiner höchsteigenen Behausung (Wohnung) monatlich 30 fl. W. W.« — Ich wohnte zu selber Zeit beim Buchhändler Geistinger am Kohlmarkt, wo mich Schubert oft besuchte und mehrmals bei mir übernachtete.

Erinn p. 211f. Anselm Hüttenbrenner to Franz Liszt, 1854.

Here's that manuscript:

The autograph of Franz Schubert's Originaltänze Nr. 2 'Trauerwalzer', 1818, in the Library of Congress. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab (5097 x 3859 px).]

The joking style is quite characteristic for Schubert, who, in response to Anselm's request for a definitive manuscript, satirically overshoots the mark with detail in providing the documentation of his authorship: not only person, date ('year of Our Lord') and place but also the rent that Anselm was paying Geistinger for his 'hutch'. A Behausing is a very derogatory term for accommodation that is temporary or low grade – were it on the ground you might call it a 'hut' or a 'shack'. In that context 'very own' is finely sarcastic. Franz tells us jokingly that he and Anselm's friendship spans the three social levels of beverages: coffee (the coffee-house everyday), wine (the booze-up in the tavern) and punch (the drink at the salon or, later, the Schubertiade).

One difference between the text of the note on the inkblot autograph and the Trauerwalzer autograph is language competence. On the Trauerwalzer autograph, Schubert's note is witty and alert; on the Forelle autograph it is befuddled, with no recipient, no date and no wit – it is fair to say that without the inkblot it would only be of interest to a specialist.

Handwriting

Another difference, obvious to anyone whether German speaker or not, is the poor quality of the handwriting on the inkblot autograph. In contrast, the writing on the Trauerwalzer autograph is open and legible. Admittedly the circumstances were different: the score for the Trauerwalzer is short and so Schubert had more free space after the score for his message; for Die Forelle, on the other hand, he had to write a very full page of music and two stanzas of text, followed by a second page of music and text for the third stanza. He was very busy that midnight hour, so perhaps his hasty handwriting is understandable to some extent.

The complexity of that task undertaken at the end of a boozy evening is testimony to the value of Schubert's gift to the Hüttenbrenners.

The texts on the first page of the inkblot autograph.

geschrieben am 21. Februar 818 Nachts um 12 Uhr. | Die Forelle. Von Schubart | ins Musik gesetzt von Franz Schubert manu propria | Eben als ich in Eile | das Ding bestreuen | wollte, nahm ich, etwas schlaftrunken | , das Tintenfaß und goß es | ganz gemächlich darüber. | Welches Unheil!

Image: ©Figures of Speech.

The texts on the second page of the inkblot autograph.

Theuerster Freund! | Es freut mich ausserordentlich, | dß Ihnen meine Lieder gefallen. | Als einen | Beweis meiner innigsten | Freundschaft, | schicke ich Ihnen hier ein anderes, | welches ich eben jetzt bey | Anselm Hüttenbrenner | Nachts um 12 Uhr geschrieben habe. | Ich wünsche, dß ich | bei einem Glas Punsch [nähere Freundschaft mit Ihnen schließen könnte. Vale.] (This line is indecipherable on the facsimile.)

Image: ©Figures of Speech.

The Hüttenbrenners

The fable that Schubert had composedDie Forelle in Anselm's rooms that night also took hold not just because of Schubert's imprecision but also because of various loose assertions by the Hüttenbrenner brothers. As we noted in respect of the Unfinished Symphony, the Hüttenbrenners are unreliable witnesses.

An engraving of Anselm Hüttenbrenner by Joseph Teltscher (1801-1837), done in 1825. Anselm would have been around 31 years old, Schubert 28.

By the mid-1850s they were in their 60s and their mental faculties had seriously deteriorated – Anselm admitted as much in a letter to Ferdinand Luib, one of the first would-be Schubert biographers:

I would sincerely like to give you sufficient information for all your questions; but my memory is already going; the memories mix and fly around wildly and I am afraid of reporting truth mixed with errors, which would not serve your purpose well, dear Sir.— I will write of all kinds of things today, and be so good as to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Herzlich gerne möchte ich Ihnen über all Ihre Anfragen genügende Auskunft geben; aber schon verläßt mich das Gedächtnis; die Erinnerungen fliegen bunt durcheinander, und ich besorge, Wahres mit Irrtümlichem vermengt zu berichten, womit Euer Wohlgeboren durchaus nicht gedient sein könnte.— Ich werde auch heute Allerlei mitteilen, und haben Sie die Güte, den Weizen von der Spreu zu sondern. [Erinn 78]

We not only have to struggle with mental confusion. The Hüttenbrenners careers had both stalled a long time before: Anselm had turned from music to an interest both in Pietist theology and in magnetism, one of the odder mental combinations; Joseph had just stayed as a low-rank administrator. They were therefore both interested – Joseph more than Anselm – in exploiting their connection with Schubert, who after nearly thirty years of neglect was now becoming a person of great interest in the musical world of Europe, not just Austria.

So we hear from one or the other or both of them at various points that Schubert had composedDie Forelle that night in Anselm's rooms, that Schubert had dedicated it to Joseph and had done so because trout were fished on the Hüttenbrenner's estate in Graz. [Erinn 90]

Anselm Hüttenbrenner in a reproduction of a water-colour, date unknown.

The idea that Schubert had composed the song in Anselm's rooms is absurd – we only need to ask where, at that drunken moment around midnight, Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart's (1739-1791) text came from? Anselm doesn't mention the source and so we are left to imagine that Franz Schubert had come to call with a copy of the Viennese edition of Schubart's poems in his pocket, or that he knew the poem by heart, or that the book was on Anselm's shelves in his hutch. No, the Hüttenbrenners' story of the composition of Die Forelle makes no sense.

The suggestion that Schubert dedicated the song to Joseph is equally far-fetched. For the dedication of an artistic work to a particular person a quite specific procedure had to be followed to invoke the written consent of the recipient of the dedication. It was then usual for the dedicatee to thank the artist for the dedication with a gift or money. Once that procedure has been followed the dedication is as much a part of the title of the work as the composer's own name. Dedicating a work without the explicit consent of the dedicatee was a social faux pas, which would not endear the composer to the dedicatee but just create an unwelcome feeling of indebtedness or obligation on the part of the dedicatee.

Despite all his wishful thinking, Joseph Hüttenbrenner's name never appears (to my knowledge) on any manuscript or printed score of Die Forelle. The piece was therefore never dedicated to him, but merely sent to him in an autograph copy.

Joseph Hüttenbrenner, no date, reproduction of a water colour presumed to be by Joseph Danhauser (1805-1845).

The Hüttenbrenners were also keen to tell enquirers that they had 'important manuscripts' of Schubert's works. Readers will remember their manuscript collecting habits in relation to the Unfinished Symphony. The value of the inkblot autograph of Die Forelle would have been greater than most autograph scores, of course, not simply because of the song's massive popularity but because Schubert's drunken ramblings in the note on the manuscript add human interest and thus elevate the inkblot autograph to a special status and value – just the sort of thing that collectors like.

Furthermore, the backstory of the autograph can be read as suggesting that it had been in some way made over to Joseph by Schubert, unlike the Unfinished Symphony which somehow – unconvincingly – had just come into his possession.

Anselm Hüttenbrenner in a lithograph from 1837. Anselm would have been around 43 years old, Schubert had been dead for about nine years.

Responding to an enquiry in 1854 from Franz Liszt (1811-1886), who was an admirer of Schubert's music and who was toying with the idea of writing a biography of him, Anselm recounted the tale of the inkblot manuscript:

One evening I invited Schubert round, since I had received a number of bottles of red wine as a present for several sessions of accompanying I had carried out. After we had emptied the bottles of noble Szekszárd wine to the last drop, he sat down at my desk and composed the wonderful song Die Forelle, that I still have in the original. – When he was almost finished and already drowsy, he took the ink instead of the blotting sand, leaving several bars almost unreadable. – He wrote in the margin of the score the following note: '[…]' – That was on 21 February 1818 at 12 o'clock at night.

Eines Abend lud ich Schubert zu mir, da ich aus einem angesehenen Hause etliche Bouteillen roten Wein als Präsent für mehrmaliges Akkompagnieren erhielt. Nachdem wir den edlen Sexarder bis auf den letzten Tropfen geleert hatten, setzte er sich an mein Pult und komponierte das wunderliebliche Lied »Die Forelle, das ich noch im Original besitze. — Als er ziemlich damit fertig war, nahm er, schon schläfrig, Tinte statt Streusand, wodurch mehrere Takte beinahe unleserlich wurden. - Er schrieb auch am Rande des Notenblattes folgende Anmerkung: '[…]' — Das war am 21. Februar 1818 nachts um 12 Uhr. [Erinn 208]

Given the general confusion of Anselm's mind, we should not perhaps try to make much of the fact that nowhere in his account does Anselm mention that this important manuscript was written for his brother.

Another puzzle that we have to leave unanswered is the question of why Schubert was attempting to sprinkle sand on the first page of the manuscript. Why he was doing this when, as Anselm tells us, he was 'almost finished' is a mystery. If he he had just written the second page and the message on it – why was he sanding the first page?

Why was this score written?

However, Anselm's account allows us to answer provisionally the question we have left unasked so far: why, after midnight, before leaving or crashing for the night in Anselm's 'hutch', did Schubert take a sheet of scored paper, write out his song Die Forelle and personalise it – not 'dedicate', personalise it – with Anselm's name?

The obvious reason would be that the piece was written as a gift to Anselm in return for the copious amounts of Anselm's wine that they had consumed together. It would, in fact, be surprising if such reciprocity had not occurred. As we noted above, it was an extremely generous gift that involved appreciable time and effort on Schubert's part.

Once we accept that, we can also easily imagine Anselm asking Schubert to memorialise the autograph not to him but rather to his brother Joseph, who had expressed such fervent admiration for Schubert (a fervour that would later become quite irksome to Schubert once the pair really did 'get to know each other better').

This scenario might explain the overstated warmth of the greeting; it might explain why the only name in the message is Anselm's and why his name is written out so fully and explicitly; it might even allow us to include Joseph's odd recollection that he received that particular piece because trout could be fished for on the Hüttenbrenners' family estate. And finally it might explain to some degree the tortuous construction of Schubert's message, in that it had to jump through two language hoops at the same time: acknowledge his debt of hospitality to Anselm whilst greeting brother Joseph in Graz.

That red wine thing

Hungarian wines were held in high regard in the Austrian Empire of Schubert's day. They were probably a welcome change from the local Austrian red wines, drunk young and vinegary, that Dr Zacharias Wertheim characterised as 'astringent and fizzy' – the addition of whatever came to hand to make them at least half-drinkable only added to the damage to the human body caused by their consumption. Even foreign wine, wrote Wertheim, 'not only may have never seen the soil of its supposed country of origin, but also not the slightest trace of grape juice might be found in it'. [Wertheim 139]

I can attest to the potency of the Szekszárd wine of Hungary from my student days. By that time, trading unjustifiably on its earlier fame and ruined by Stakhanovite mass production, Szekszárd had entered the student's price category and was definitely not a wine that one would gift to anyone for whom one had any regard at all. It was, though, a balanced companion for that other staple of my student days, the onion curry. For the wine, the word 'memorable' could replace 'noble'; for the curry, 'unforgettable' is probably best.

In another pointless aside we note that after about 1870, that is, about 20 years after Liszt's contact with the Hüttenbrenners, the town of Szekszárd would become a favourite and frequent haunt of the great man himself, a place still memorialised in his Szekszárd Mass, correctly Missa quattuor vocum ad aequales concinente organo, created in 1869 by Liszt for his close Hungarian friend, Baron Antal Augusz.

When was Die Forelle composed?

Some scholars have been led astray by the befuddled German of Schubert's message on his autograph: he writes that he has just now 'written' the score, when he really means 'written down', 'written out' or possibly even 'copied out'. The latter would not really be an improvement, since Schubert is not copying out from anything, it's all in his musical mind.

Maurice Brown, in his 1965 review of the manuscripts and early printings of Die Forelle, points us to the key witness for the date of the creation of the piece, Johann Leopold Ebner (1791-1870). [Brown 578f]

Ebner was a pupil in the Vienna Stadtkonvikt when he got to know Schubert, who, although he had left by then, returned frequently to visit his friends there. He recounted to Ferdinand Luib his recollection of the moment Die Forelle was born:

About Schubert's life I unfortunately know very little, although I still remember one strange happening very well. When Schubert composed the song Die Forelle he brought it on the same day to us in the Konvikt to try it out. It was played repeatedly with great enjoyment. Suddenly Holzapfel cried 'Heavens, Schubert, you got that from Coriolanus'. In the overture of the opera there is a place which is similar to the piano accompaniment of the Forelle. Schubert saw this himself and wanted to destroy the song, but we didn't allow him to do that and so rescued this wonderful song from doom.

[Innsbruck, am 3. Mai 1858.] Über Schuberts Verhältnisse weiß ich leider nur sehr wenig; eines komischen Falles entsinne ich mich aber noch recht lebhaft. Als nämlich Schubert das Liedchen 'Die Forelle' komponiert hatte, brachte er es am selben Tage zu uns ins Konvikt zum Probieren, und es wurde mit dem lebhaftesten Vergnügen mehrmals wiederholt; plötzlich rief Holzapfel: »Himmel, Schubert, das hast du aus dem 'Coriolan'.« In der Ouvertüre jener Oper ist nämlich eine Stelle, die mit der Klavierbegleitung in der 'Forelle' Ähnlichkeit hat; sogleich fand dieses auch Schubert und wollte das Lied wieder vernichten, was wir aber nicht zuließen und so jenes herrliche Lied vom Untergang retteten. [Erinn 54]

Brown notes that Luib was still fixed on that moment in Anselm Hüttenbrenner's room on 21 February 1818 as the moment that Schubert had composed Die Forelle. He wasn't relying on the Hüttenbrenners' description of that occasion, but on Schubert's own tipsy statement that he had 'written' it there and then. On this basis, Luib seems to have suggested to Ebner that he might be mistaken, which resulted in a slightly aggrieved response from Ebner:

Concerning the time of the creation of Schubert's song Die Forelle, irrespective of the statement of the shambolic Schubert, I have to stand by my statement that it happened before the year 1817. Stadler and Holzapfel will confirm it: the anecdote that he [Schubert] wanted to destroy it after Holzapfel pointed out the similarity with Coriolanus took place in my presence and was literally true. I left Vienna at the end of August 1817, never to return. Schubert had probably made the work public in February 1818 after having composed it in 1816.

[Innsbruck, am 4. Juni 1858.] Rücksichtlich der Zeit der Entstehung von Schuberts Lied 'Die Forelle' muß ich ungeachtet der Angabe des Schurimuri Schubert bei meiner Angabe, daß es vor dem Jahre 1817 war, beharren; Stadler und Holzapfel müssen es bestätigen: die Anekdote, daß er es, als ihn Holzapfel auf eine Reminiszenz aus 'Coriolan' erinnerte, vertilgen wollte, wo ich dabei zugegen war, ist buchstäblich war, und ich bin Ende August 1817 von Wien abgereist und nie mehr dahin gekommen; wahrscheinlich hat Schubert das bereits im Jahre 1816 komponierte Lied erst im Februar 1818 der Öffentlichkeit übergeben. [Erinn 57]

Johann Ebner is a highly credible witness and his account is remarkably detailed and corroborated. We have to respect his confident certitude in the face of the shambolic Schubert's own note. The similarity with the 52nd bar of Beethoven's overture to Coriolanus is apparent. [Erinn 58] Schubert's unrelenting honesty is described by several commentators on his life, among them Anselm Hüttenbrenner:

Schubert was also utterly honest, genuine and sincere. At that time he lived – just between ourselves – a life much purer than I did…

Schubert war auch grundehrlich, wahr und aufrichtig, und er lebte in jener Zeit (unter uns gesagt) viel reiner als ich…[Erinn 81]

Although we do not have an exact date we can therefore be quite confident that Die Forelle was composed in late 1816 or early 1817.

We also have to thank Ebner for making us aware that one of Schubert's most popular creations came very close to being stillborn – which, in turn, would have had an effect on the albeit limited fame of its lyricist Christian Schubart. Without Franz Schubert's setting of his prison poem Die Forelle, Christian Schubart would be even more of a footnote in a history textbook.

The manuscript and printed scores

Ignoring the Hüttenbrenners' ramblings and working only from demonstrable evidence the history of the manuscript of Die Forelle can be reconstructed with some certitude.

Schubert frequently dashed off copies of his shorter works from memory. In the case of Die Forelle we are fairly confident that there were seven(!) manuscripts of the song, all with slight variants that can be reduced to five versions, written down from memory by Schubert himself. The variants are just that – variants: there is no trace in the manuscripts of a development process taking place in the music between 1817 and 1825, the song's first proper publication.

Here's your handy cut-out-and-keep guide to the manuscript and printed scores of Die Forelle:

Ms_1, V_1: The autograph of the original version of the score, now lost, dated from the early part of 1817 or perhaps even late 1816. This would be the autograph that, Ebner tells us, Schubert brought into the Stadtkonvikt on the day of its composition.

Ms_2, V_1: A manuscript copy made of the original, now lost.

Ms_3, V_1: A manuscript copy made of the original, now lost.

Ms_4, V_1: The original autograph was transcribed into a manuscript song book (dated 1817) by Albert Stadler (1794-1888), whom Schubert had met at the Vienna Stadtkonvikt (1812-1815). The manuscript of the song book is now in the University Library of Lund in Sweden, where there is a major collection of Schubert manuscripts. Stadler made a habit of copying Schubert's early works into his album: it is he whom we have to thank for preserving around eighty of Schubert's earliest works.

Ms_5, V_2: In July of 1817 Schubert wrote the score in the music album of Franz Sales Kandler (1792-1831), another former pupil of the the Stadtkonvikt (1802-1808). This score contains the second version of the song.

Ms_6, V_3: The inkblot autograph for Joseph Hüttenbrenner contains the third version of the song. Here for completeness is the first page once more:

The first page of the facsimile of the inkblot autograph of Die Forelle, containing the first two verses of the song, the alien date, the title and Schubert's explanation for the inkblot. Image: ©Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Musiksammlung. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab (2176 x 1601 px).]

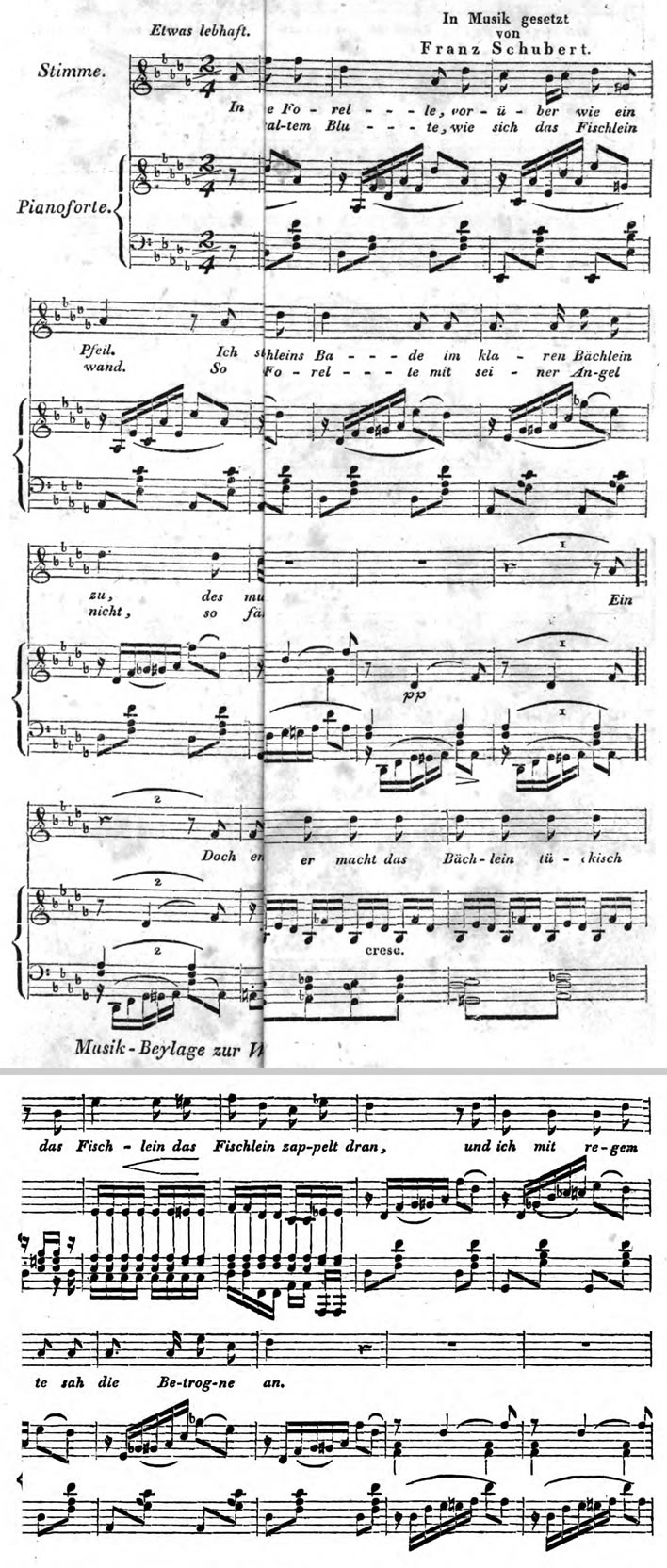

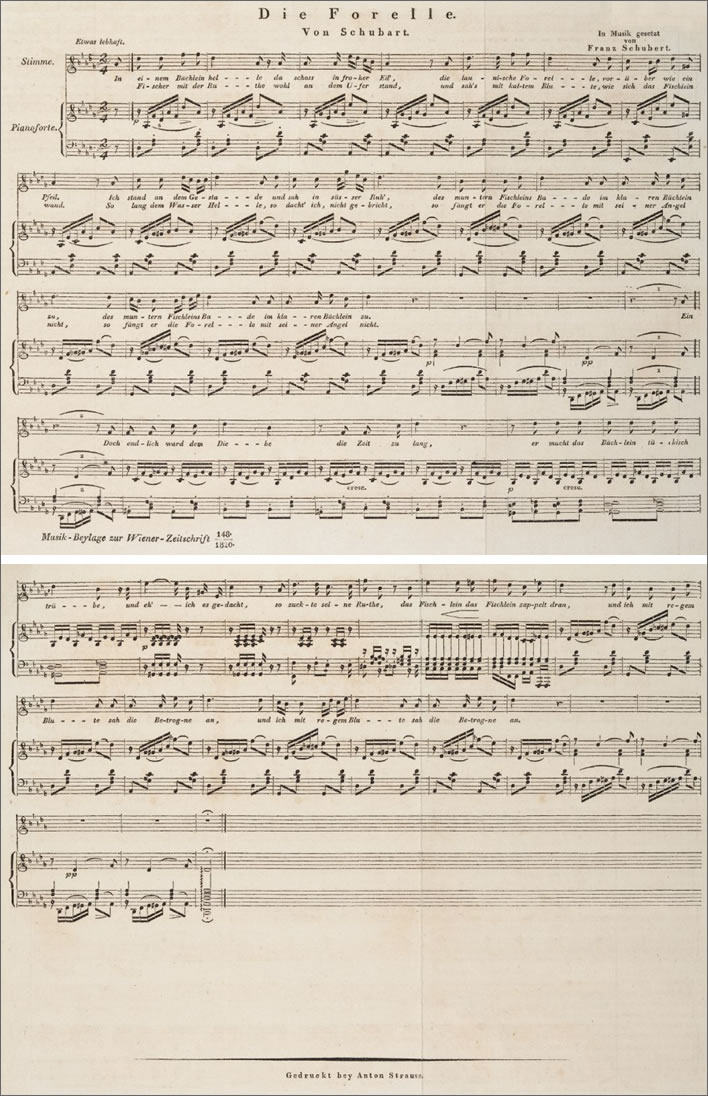

V_4a: Not a manuscript. The score of Die Forelle was printed in the music supplement of the Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode– a.k.a. Mode Zeitung or Wiener Zeitschrift– on 9 December 1820. This was the fourth version of the song and the third Schubert song ever to be published. [Dok 112n]

Die Forelle in the the music supplement of the Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode on 9 December 1820. Unfortunately the page was still folded when scanned. Image: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode, 1817-1848. Sa, 9. Dezember 1820, p. 9f. ANNO. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab (1353 x 3180 px).]

The version of Die Forelle from the Wiener Zeitschrift printed by Anton Strauss. Strauss was the printer of the Wiener Zeitschrift at that time. Image: Library of Harvard University. Schubert, Franz, 1797-1828. [Songs. Selections]. Erstausgaben aus der Wiener Zeitschrift, [1820-1832] / Franz Schubert. [Wien]: A. Strauss, 1820-1832. Merritt Mus 800.1.703 PHI. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab (1367 x 2148 px).]

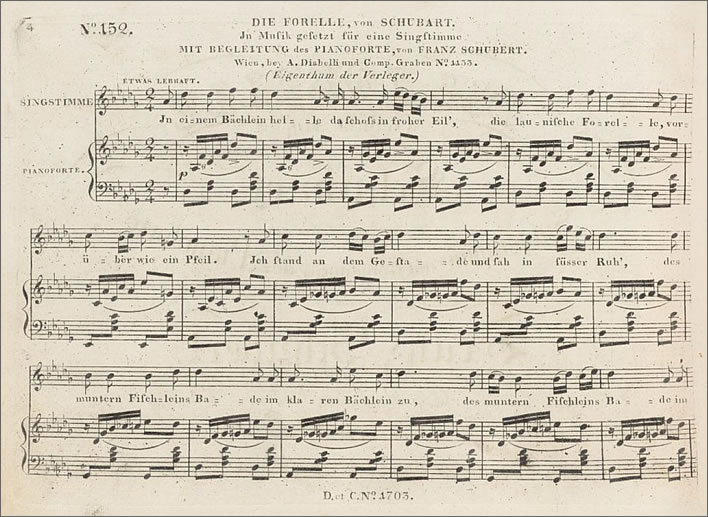

Ms_7, V_5 + Intro_1: The last written autograph we have, containing the fifth version of the song. It was written down in October 1821. This version is notable for its five-bar piano introduction by Schubert. It was normal at the time for the pianist to improvise an introduction to a song, but in this instance Schubert added the introduction himself and saved the pianist the bother.

Autograph score of Die Forelle dated 1821 in the Library of Congress. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab (5144 x 3756 px).]

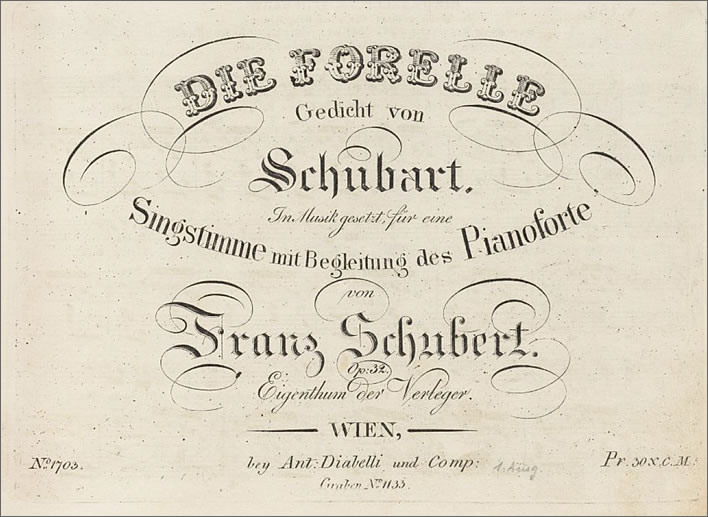

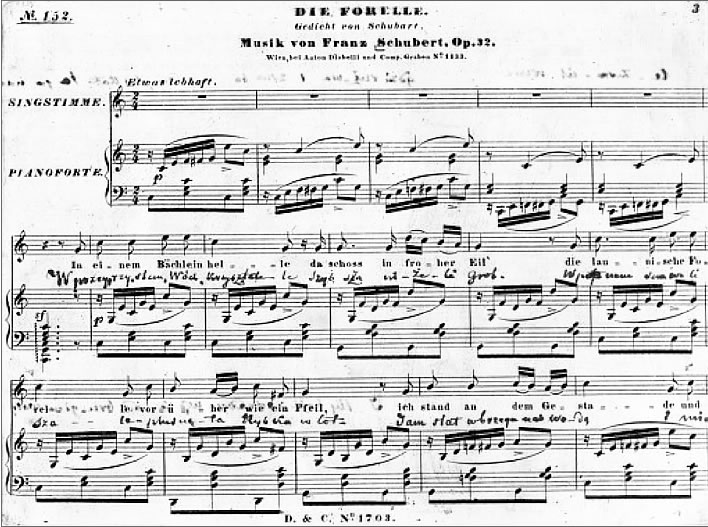

V_4c: Not a manuscript. The song was announced by the Viennese music publisher Anton Diabelli in the Wiener Zeitung on 13 January 1825 as Opus 32. This edition followed very closely the score that had appeared five years before in the Mode Zeitung. Diabelli published it as number 152 of his series 'Philomele'.

The publication of this score seems to have been done in a rush: Diabelli made no attempt to simplify the piece to extend the sales appeal to a wider circle, which would have been normal for the pieces in his 'Philomel' series. He left it, for example, in the tricky key of D-flat major; he also made it very clear that this potential bestseller was now his property, Eigenthum der Verleger, 'Property of the Publisher', both on the cover and on the first page; he did not add a piano introduction.

Anton Diabelli's first edition of Die Forelle in his Philomel series. Tope: title page. Bottom: first page of the score. Image: Harvard University - Eda Kuhn Loeb Music Library / Schubert, Franz, 1797-1828. [Forelle (Song)]. Die Forelle / Gedicht von Schubart; in Musik gesetzt fur eine Singstimme mit Begleitung des Pianoforte von Franz Schubert. Wien : bey Ant. Diabelli, [1825]. Merritt Mus 800.1.705 PHI. [Click on the images to open a large version in a new tab (1298 x 948 px).]

V_4d + Intro_2: Not a manuscript. Diabelli produced his simplified version almost simultaneously with the previous original version. The piece was transposed from the complex D-flat major key to the much simpler C major key – although the simplicity of the signature is paid for with a large number of accidentals. A six-bar introduction was added by recycling the last six bars of the piece.

Anton Diabelli's 'simplified' version of Die Forelle. Still number 152 in the 'Philomele' series, still Opus 32 and still plate 1703 – that will keep the musicologists busy!

V_4a + Intro_2: Diabelli had a hit on his hands. In 1829, the year after Schubert's death, he published the Neue Ausgabe, the 'New Edition' of Die Forelle. Just to keep the musicologists even busier, the song went back to its original key, D-flat major, (for soprano and tenor) but kept Diabelli's six-bar introduction. He also added a transposition to B major for baritone and alto.

The modern 'open' score

Tracking the many print variants that resulted from Diabelli's busy publishing activity is beyond the scope of the present article. Let's skip the intervening century and a half.

The latest edition of Die Forelle is that of the Neue Schubert-Ausgabe, Serie IV, Lieder, Band 2, Teil a, p. 109. It does not define a definitive version, leaving that choice to the performers. Instead, it reproduces all the variants but takes the fourth variant (V_4c, Diabelli, 1825) as its standard but without Diabelli's six-bar introduction. As an option, Schubert's five-bar introduction (Intro_1) is reproduced.

Afterthoughts and loose ends

Just a few more pointless asides and then we can all hunker down with some bottles of Szekszárd Bikavér ('Bull's Blood') [No!] and an onion curry [NO!] and pass the time until the 300th anniversary comes round.

Whilst searching in the Oxford English Dictionary for the correct English terminology for the act of sprinkling sand on a freshly written text (corresponding to the German bestreuen) I stumbled across a reference to a similar misadventure in James Beresford's The Miseries of Human Life, first published in 1806. It is clear that Schubert's calamity with the inkpot seems to have been a quite common occurrence:

Emptying the ink-glass, (by mistake for the sand-glass,) on a paper which you have just written out fairly—and then widening the mischief, by applying restive blotting paper.

Beresford, James (1764-1840). The Miseries of Human Life; or the Groans of Samuel Sensitive, and Timothy Testy. With a few supplemental sighs from Mrs. Testy. In Twelve Dialogues. London, William Miller, 1806. Dialogue 8, 24.

NB: 'restive' indicates that the blotting paper obstinately refuses to absorb ~ resistive.

Beresford's Miseries sold in immense numbers over the years and went through a number of further editions. The fourth edition is available online at archive.org.

Anyone glancing at the design of writing-sets down the ages will notice the tendency of designers to go for beautiful symmetry in all things as opposed to practical ergonomics, right down to modern times. They really should know better by now. At 150 kmh in my car it has not been unknown for me to splash the ink when I meant to sprinkle the sand.

From the Miseries of Human Life we pass elegantly to the miseries of the young Werther in Goethe's gloomy Briefroman, 'epistolary novel', Die Leiden des jungen Werther, 'The Sorrows of Young Werther' (1774), an old friend of ours on this website. A book based on letters had somewhere to include a passage referring to the use of blotting sand – which indeed it does.

26th July

Yes, dearest Lotte, I will arrange and order everything; only give me more requests and very often. And one thing I ask of you: no more sand on the notes that you write to me. Today I lifted it quickly to my lips and afterwards my teeth were grinding.

Am 26. Julius.

Ja, liebe Lotte, ich will alles besorgen und bestellen; geben Sie mir nur mehr Aufträge, nur recht oft. Um eins bitte ich Sie: keinen Sand mehr auf die Zettelchen, die Sie mir schreiben. Heute führte ich es schnell nach der Lippe, und die Zähne knisterten mir.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Stuttgart: Reclam, 2013. Book 1, p. 47.Online.

The great man's many admirers will be full of admiration for the oblique way he indicates that Werther deep kisses Lotte's letters; his detractors will be chortling for quite some time at the image of Werther, in his trademark blue jacket, yellow waistcoat and seven-league boots running his tongue over Lotte's gritty letter and grinding his teeth with desire.

Werther can stand no longer the sand from Lotte's letters crunching in his teeth. He takes the easy way out.

Sources

All sources are in German, unless otherwise noted. All translations ©FoS.

| Brown | Brown, Maurice J.E. Brown, 'Die Handschriften und Frühausgaben von Schuberts „Die Forelle“' in Österreichische Musikzeitschrift, Volume 20, Issue 11, Pages 578–588. It is available online (paywall). |

| Dok | Deutsch, Otto Erich, ed. Schubert: Die Dokumente Seines Lebens. Erw. Nachdruck der 2. Aufl. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1996. [DE] |

| Erinn | —, ed. Schubert: Die Erinnerungen Seiner Freunde. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1997. [DE] |

| Wertheim | Wertheim, Zacharias. Versuch einer medicinischen Topographie von Wien : Leben und Überleben im Biedermeier. Wien : Löcker, 1999. |

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!