The real Elizabeth Layton

Werner Vogt, UTC 2018-02-01 08:14

In 1996 the author interviewed Elizabeth Nel (1917-2007, née Layton) at her home in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. Elizabeth Layton was a secretary to Winston Churchill during most of the Second World War. She was 79 at the time of the interview.

Port Elizabeth, end of August 1996

Yes, of course she would speak about her experiences on Winston Churchill's staff, said Elizabeth Nel over the phone. There was so much nonsense being written these days about the events of those times and about Churchill's character that she would be happy do her bit to correct this.

That lively first-impression continued into the face-to-face meeting, too. While she drove her guest through Port Elizabeth, the harbour town that had become her second home, she talked about the local sights as well as episodes from the old days in Great Britain.

The winding road to London

Elizabeth Layton, as she then was, came into Churchill's service by a roundabout route. She was a seven-year-old in 1924 when her family emigrated to Canada. Twelve years later she returned to London where she trained and got her first job as a secretary – which lasted until 1939. She was back in Canada at the outbreak of the war on 1 September 1939, but some family issues prevented her crossing the Atlantic again.

In the spring of 1941 the young woman was convinced that she could and should do something for England. In 1938 she had already successfully trained as a volunteer air warden. But the Canadian authorities refused to permit her to return to Britain at first. She went to Ottawa in person to battle for her right to travel to London. Finally a wearied civil servant gave in, stamped her passport and sent her off with the words 'If you want to commit suicide, that's your own business'.

Good references and a cousin who was a commander in the Navy helped Elizabeth Nel with her application for the post of Secretary in 10 Downing Street. She realised soon after starting the job that this post would require some talents beyond skill in typing and shorthand.

Elizabeth Nel, née Layton, was personal secretary to Winston Churchill, 1941-1945. This is a photograph of her taken at some time during that period. She was born on 14 June 1917 and died in her sleep on 30 October 2007, aged 90.

The British Prime Minister demanded from all his staff – from ministers through officers of the General Staff down to his private secretary and his driver – a level of commitment and as perfect a service as possible without time limits. Two o'clock in the morning was a frequent time for the end of work. When necessary Churchill even worked until four o'clock.

The first meeting with Churchill

Churchill disliked having to adjust to changes among his close staff. He was used to a work schedule in familiar surroundings that ran with the precision of a clock. For this reason in the first weeks after the start of her job on 5 May 1941, Elizabeth was not even let near the lion's den. When the moment finally arrived she was extremely nervous. She knew that Churchill had many virtues, but she had been told that patience was not one of them.

She entered the Prime Minister's office with gloomy foreboding. Churchill was walking up and down dressed in a one-piece siren suit, a sort of blue boiler suit that the Royal Air Force used. Without any polite small talk he told the new secretary that he wanted her to take a dictation directly on the typewriter. All the typewriters in the room were set to double spacing, since the Prime Minister heavily edited the first draft of most texts.

As it happened, Elizabeth Nel set herself down at just the one machine that had been set to single spacing. The speed of the dictation allowed no time to change over and so the inevitable happened: Churchill, walking up and down, noticed the error and gave his anger free rein. He concluded his outburst with the wish that she should leave immediately and fetch a more competent colleague.

The recipient of this rebuke did not allow herself be deflected from her task. Like everyone else around Churchill she was aware of the enormous responsibility that rested on his shoulders and put the incident behind her. The USA had still not entered the war and the British were still far removed from the military luck that El Alamein and Stalingrad would bring.

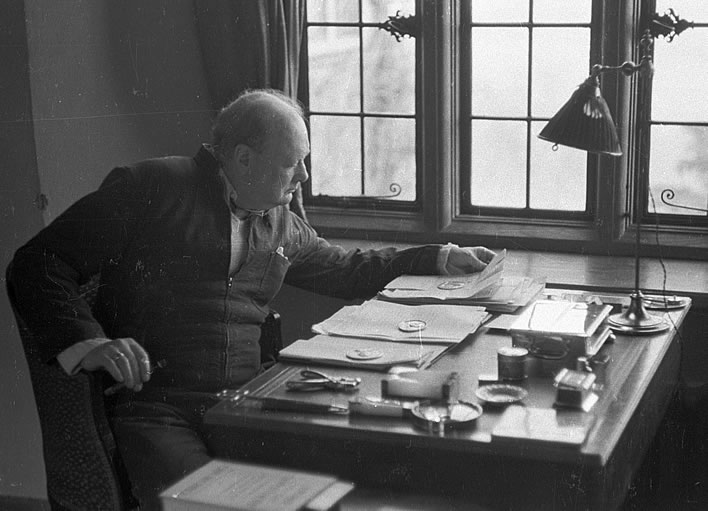

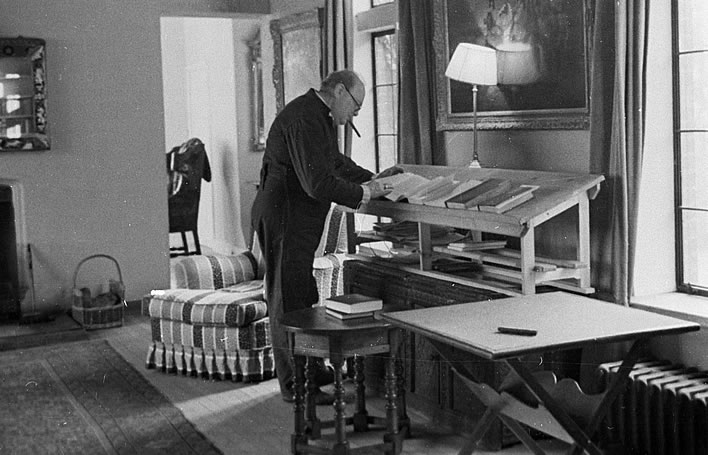

Churchill in his siren-suit in his country home Chartwell in 1939. Images: Kurt Hutton/Picture Post.

Tears for the Navy

Elizabeth's next task took place under more favourable circumstances. In the Hawtrey Room in Chequers, the country house of the British Prime Minister, she took dictation on the great report on the state of the war that Churchill wanted to present to Parliament. The statesman walked his circuit of the room, smoking. He sometimes had a previously typed paragraph read back, polished the formulations and re-lit the cigar that had gone out during his pause for thought in great clouds of smoke. Churchill, according to Elizabeth, delivered his speeches as an actor would, even in the process of their creation.

As a previous First Lord of the Admiralty his thoughts were still always so much with the sailors that he unavoidably wept when he had to report the losses of ships and seamen to Parliament. When attempting to spur on the workers in the armaments industry to even greater efforts he spoke with a harder tone. Whenever the talk was of Hitler, his voice sank to a deep growl, which he used to designate 'this evil man'.

'How much so far?' he asked at four-thirty in the morning. 'Almost 10,000 words' was the answer. At that moment she realised that she had passed the test of fire. Churchill said considerately that she didn't need to produce the fair copy immediately – she should sleep a couple of hours first. It was astonishing, she said, looking back, how quickly one had got used to doing with only a minimum of sleep.

Even today Elizabeth Nel's words, in their formulation as in their cadence, bear witness to her admiration for him. She has an enormous respect for her one-time boss and always refers to him as 'Mr Churchill'. He had demanded the utmost from all his staff, who in turn had readily responded in the face of his own sacrifice and in the interest of the great task of defending the freedom of Europe.

Churchill never showered her with compliments but, on the other hand, even in a fit of temper he never failed to give an unspoken acknowledgement of respect. She always felt herself to be a colleague not a servant. He never had any tendency to flirt. His marriage to Clementine was such an emotional reservoir for him that he never allowed any ambiguity to appear – a fact that made taking shorthand in Churchill's bedroom much easier. The premier often conducted a large part of his morning's administrative work lying on his bed.

Kicking the cat

One of the most humorous events that Elizabeth Nel remembers occurred during a dictation in Churchill's bedroom one morning. The wartime leader was wearing his famous dressing gown with the golden, green and red dragon and was on the telephone with the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir Alan Brooke. Churchill's cat Smokey was sitting next to him on the bed cover. What Churchill heard on the phone was clearly so animating that he kept waggling his toes jerkily, a movement that aroused the hunting instinct of the cat, who sprang without warning onto the prey.

Churchill shouted out and kicked the cat with his other foot. Heedless of the telephone conversation, he shouted at the cat 'Get off, you fool!' Sir Alan Brooke, the later Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke, was already mystified by this interjection. When Churchill saw the cat in the corner of the room, licking itself with a dazed expression, he said 'Poor little thing', at which point Sir Alan put the phone down and contacted the duty Private Secretary to enquire about Churchill's general state of mind.

Elizabeth Nel remembers in particular the many exciting journeys with Churchill. The wartime prime minister was greeted by people everywhere with enthusiasm, particularly in her second home, Canada, as well as in the USA. Particularly memorable were meetings with the leading statesmen of the allied world, with Franklin Roosevelt, with the Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King, South Africa's leader Jan Smuts or with Stalin, as well as Atlantic crossings on board the Queen Mary or the battleship Prince of Wales, later sunk by the Japanese.

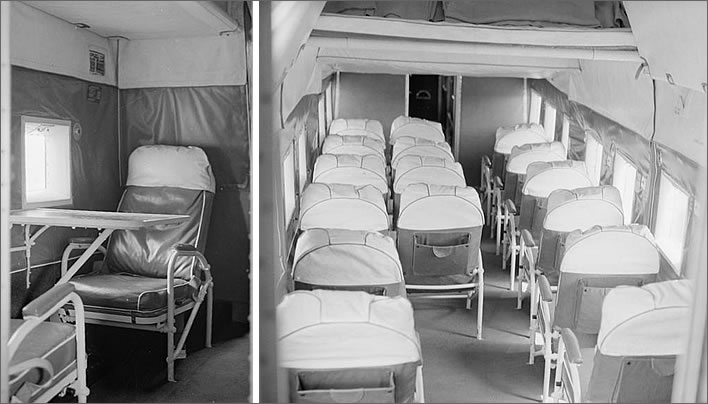

Notable were also the flights in the Liberator bomber reserved for the Prime Minister, which Mrs Nel remembers as though it were yesterday. It had been, she recalled, sometimes difficult to write with frozen fingers the last reports before the landing of the aircraft.

Churchill's personal aircraft was a converted US Liberator II long-range bomber, named by him 'Commando'. It was in service with him from July 1942 to September 1943. The photograph bottom left is of Churchill's cabin; bottom right the VIP cabin. The heating system was rudimentary and generally ineffective. The aircraft was lost on 27 March 1945 over the North Atlantic for unknown reasons. Images: © IWM

But not only the continual coming and going of the messengers of the armed forces, the government couriers and dignitaries of all levels contributed to the fascination of her work. As Churchill's secretary, Elizabeth Nel was privy to the best-kept state secrets, such as 'Tube Alloys', the plan for the development of the atomic bomb.

The last stone in the mosaic

In 1945 Elizabeth Layton made the acquaintance of Frans Nel, the man from Pretoria who would become her husband. At the outbreak of the war Lieutenant Nel joined up to fight for the free world, against the wishes of his Boer family. He was taken prisoner by the Germans at Tobruk. In the autumn of 1945, when the Conservative party's defeat at the general election made Churchill a private individual once more, Elizabeth Layton moved to South Africa. The circumstances of the couple, who had three children, did not permit a reunion with the wartime prime minister in far-away Europe.

That separation enhanced the emotions when Elizabeth Nel and her husband were invited in 1990 by the Prime Minister of the time, Margaret Thatcher, to 10 Downing Street.

One of the guests at the celebratory dinner with former British prime ministers and relatives of the wartime premier expressed the situation before Winston Churchill's elevation to the highest position on 10 May 1940 as follows: In the incomparable mosaic of Churchill's life, in which up to 1939 he had occupied almost all the key ministerial positions, one mosaic piece had been missing: the leadership of Great Britain in the darkest days of its history. Had this calling been a higher dispensation?

Former Churchill secretaries Elizabeth Layton-Nel (1941-1945) and Lady Williams, the former Jane Portal (1949-1955), at a reunion in 2006.

Lily James as Elizabeth Layton in the film Darkest Hour (2017). Image: photograph by Jack English, ©2017 Focus Features LLC.

The German original of this article was published in the Neue Zürcher Zeitung on 19 September 1996, No. 218, p. 9. This translation ©FoS 2018.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!