3 April 2018: Happy birthday, Balsamico!

Richard Law, UTC 2018-04-03 09:12

Bologna in April 1998, twenty years ago this month.

Tiring of its butchers,

its cheese shops,

its fruit, vegetable and herb shops,

its cheese, sausage and ham shops,

its fish shops,

its corner shops,

its bars and coffee shops,

we took the train to Modena. Something was missing and Modena was the place to find it.

Barely thirty minutes of Italian railway and then a zig-zag ten-minute walk through the town, heading for the Palazzo Ducale di Modena.

Then only a few steps more towards the Via Luigi Carlo Farini. Here's what we are looking for, number 75, Guiseppe Giusti, salumeria.

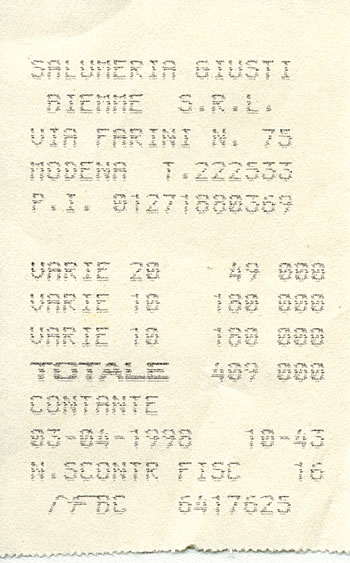

There on 3 April 1998, at 10:43 precisely (see the till receipt below), we bought two bottles of Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena D.O.P extra vecchio.

Vaut le voyage? Of course: twenty years later, there is still some left in the sole survivor:

Wastrel! Profligate! What would your parents say? 180,000 lire for a 100 ml bottle of vinegar? And two bottles of it at that! How much is that in a comprehensible currency?

At the conversion to the Euro a couple of years later the equivalent would have been 93 EUR. The lump of ancient Parmigiano-Reggiano would have been 25 EUR.

But nowadays the highly variable price (shop around!) for the same balsamico is typically somewhere in the low hundreds of Euros per bottle. The food writers, the style columnists and the celebrity chefs have done their work well, don't you think?

The helpful staff in Giusti serve you samples of precious balsamico dribbled reverently onto small pieces of their finest and oldest cheese. Because you're worth it, of course.

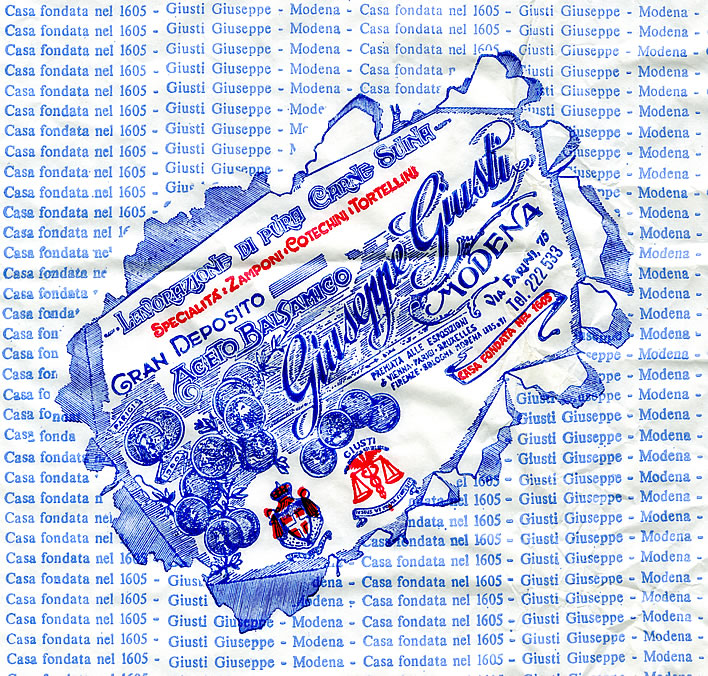

The cheese was so good, in fact, that I saved the paper in which my purchase was wrapped:

You ask: 'Why go to all this expense and trouble just for some balsamic vinegar?' Old balsamico is syrupy and dark – put a drop on a spoon or on a piece of cheese and taste it. It is not acidic or sweet or bitter: it carries hints of all of those, wrapped up in a complexity that would be worthy of the great wines of the world. There are people who take it by the spoonful as an all-purpose medicine. Forget the salad – just eat the balsamico. If you really want some calories with it, dribble a few drops on a ripe strawberry.

Another question is on your lips: 'Why was your balsamico so expensive?' Because there is balsamico– and then there is balsamico, just as there are Italian motor vehicles (e.g. Fiat Punto) and there are Italian motor vehicles (e.g. Ferrari, that other product of Modena. Balsamico and Ferrari – two objects of desire in the very same place).

'Then why', you ask, 'if it is such wonderful stuff, why have you got so much of it left after twenty years?' I don't really know, is the honest answer. Perhaps during the course of those years I have rediscovered my inner pleb – the guide who accompanied me through the cash-strapped wastelands of my teen years. I now eat more simply, more economically and do not mess around with food. Once a year, perhaps, I may encounter a strawberry, but it is consumed before the thought of decorating it with two drops of perfect balsamico even enters my head.

Losing your pretensions, like the arches of your feet falling, can be painful while the process is underway, but once completed, flatness becomes a comfortable state, which those still pert can only envy.

Twenty years ago, when I took the photos of the hunter-gatherers of Bologna tracking down their food, I thought: 'How discerning they are, how gastronomically cultured'. Now I look at those photographs and think: 'Why are these primitives wasting half a day shopping when they could feed themselves for a week more cheaply with a ten minute whizz around a supermarket buying stuff showing best-before dates?'.

So my balsamico, once so prized, now lives in a dark cupboard and ages quietly without protest – rather like its owner.

Making the stuff

In many respects, Italian culture is a unique blend of anarcho-syndicalism, communism, feudal mercantilism and shameless entrepreneurial banditry – that's what makes it so repellently attractive. The organization of the production of aceto balsamico reflects this perfectly. There are no fewer than four consortia that regulate its production. It is estimated that there are in addition about a thousand people in and around Modena making their own stuff and using it to seduce others, but principally to bribe politicians and tax officials.

Somewhere in the middle of all this productive activity millions of litres of aceto balsamico appear on the market every year. Some of it may even come from Modena. Most of it is unremarkable, not unpleasant and above all cheap.

Some of these vinegars are made from apples, some from wine and some from other things (best not ask). Then, ascending through the price range, we pass through a selv' oscura of products, some which have di Modena on the label and other dubieties.

The misleading terms on balsamic vinegar labels are in the same league as olive oil. Caveat emptor. In the end, only one word counts: tradizionale. The consortium was founded in 1979 and vigorously guards the designation.

And age? Well, in essence, money talks. Did you think it would be otherwise?

Aceto balsamico tradizionale starts its life as freshly harvested grapes (NB: not fermented wine), mashed, boiled, reduced and fermented initially in an open pan. The maximum protection is a fly net. At some moment the fermentation magic begins – when? Who knows? L'uomo propone e Dio dispone. The liquid is allowed to rest until the spring, when it is filtered and decanted into large wooden casks.

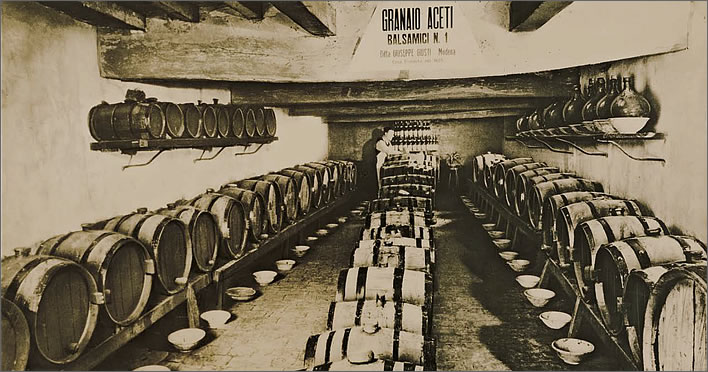

As the years flit past, Nature takes its course: leaks and evaporation (the 'portion for the angels' as the sherry makers call it, who use a similar production system termed solera) reduce the volume. Finally a portion of that vinegar is decanted and added to the existing contents of a smaller cask. Fermentation continues, sometimes faster sometimes slower, depending on the ambient conditions. The angels – ever reliable – do their job. There may be a battery of eight such casks, each one smaller than the next, its contents more ancient, more mature and more viscous than its predecessor. The process is called Rincalzi e Travasi, 'decanting and refilling'.

Top: a photograph of Giusti's acetaia ND. This shows the original set-up in the attic above the shop in the Via Luigi Carlo Farini. In 1990 production was transferred to a farmhouse in Lesignana near Modena.

Bottom: A photograph of some of Giusti's casks in Lesignana. Traces of leakage are clearly visible. Images: Giuseppe Giusti.

The casks are valuable possessions for a producer, their age and characteristics are held to impart subtlety to the product. Giusti uses casks made of various woods, most of them over fifty years old and imbued with the residues of those years, thus adding to the complexity of taste of the final product. At each stage, a portion of a balsamico of appropriate maturity can be extracted and bottled. It takes no great imagination to realise how little comes out of the small casks with the oldest content.

Unlike wine, which dates from its harvest, the age of a bottle of aceto balsamico cannot be stated exactly, because it is a combination of various ages in the production chain. One can only specify a minimum age. In the case of extra vecchio this is twenty-five years. Making a statement of the age of a particular batch is strictly forbidden, but still whispered in a roundabout way to those who choose to ask. The confirmation comes in the texture and the taste.

In practice the average age of the balsamico in my bottle is probably around thirty years, meaning that I was a young(ish) man when most of it started out on its journey down the series of casks in the battery – indeed, some molecules of it may have set off well before I was born. In the meantime the angels have had their portions of both of us.

Like the winemaker who lays down a vinyard for a mature vintage he will never see, so the producer of aceto balsamico tradizionale fills his starting cask with a product he may never get to taste.

Labels

With any Italian product, particularly wine or balsamico, it pays to study the labels very carefully. They can be full of interesting surprises. You think Giusti sold me their own balsamico, do you? You simple Anglo-Saxon person!

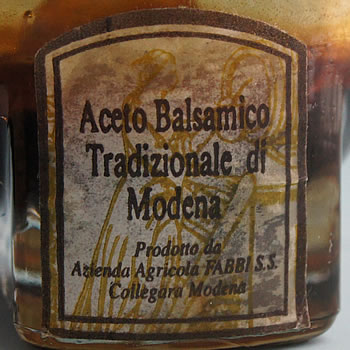

Here is the front label on my bottle of balsamico. The key word here is tradizionale. But the name of the producer is not Giusti but Azienda Agricola Fabbi in Collegara, near Modena.

This bottle was sold by Giusti in their shop but was not produced by them – for whatever reason.

Never mind. Fabbi is a member of the same consortium as Giusti, produces balsamico tradizionale with exactly the same techniques, uses casks of four different woods and ages the product in the same way. Every year the produce of all the members of the consortium must satisfy a panel of five judges, so its quality is guaranteed. Even the form of the bottle is standardised for tradizionale. There are probably connections between these two companies that no non-Modenesi can penetrate. But Fabbi's product was delicious, so if I need to restock that is where I shall go. Gusti had their chance to sell me their product but for some reason failed to do so.

The phrase extra vecchio is the term used with tradizionale to designate balsamicos with a minimum age of 25 years. The label tells us once more that it has been produced by a consorzio produttori and that it is tradizionale di Modena. It has also been ottenuto da mosto cotto a fuoco diretto a vaso aperto di uve tipiche Modenesi, 'obtained by the boiling down of Modenese grapes in open vessels' – the latter meaning that only naturally occurring yeasts caused fermentation. The result has been lungamente invecchiato e affinato in botticelle di diversi legni pregiati, 'aged and refined for a long period in casks of various woods'.

A photograph of Giusti's extra vecchio today, after the modern marketing people have finished adding their bling. It even comes in a small wooden box. Image: Giuseppe Giusti.

Fabbi's bottles have also been heavily rebranded in the intervening years.

It just seems that, in order to market aceto balsamico tradizionale the last thing you should show the paying public is anything remotely traditional.

And, finally, it must be said: the story of the production of aceto balsamico is a nice tale that may indeed apply to some bottles from the many acetaia around Modena, but there are those who claim to be able to produce the same result by taking a bottle of balsamico of reasonable quality off the supermarket shelf and reducing its contents in a saucepan until the result is a syrupy liquid that looks and tastes not unlike the tradizionale that these renowned acetaia take so long to produce. The angels get their portion in the course of not thirty years but about thirty minutes, in other words.

All images in this piece unless otherwise credited are ©Figures of Speech. Re-use is only permitted when accompanied with a link to this website.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!