Dr Groddeck will see you now

Richard Law, UTC 2018-04-01 07:22

Jan Davidszoon de Heem (1606-1683) is held to be one of the leading Dutch still life painters of his age. Such magisterial judgements are too bland in his case: he was an utter master of colour, form and accurate detail whose works make modern photographs appear rather inadequate.

'Perfection' is the only word that comes to mind to describe his handling of light and texture. Judge for yourself, for example, from just one of hundreds of jigsaws and chocolate box lids:

Jan Davidszoon de Heem (1606-1683), Still Life with Flowers in a Glass Vase (1650-1683). Image: Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab, 5220 x 7866 px.]

If we look past the painterly perfection, harmony and staged beauty we see that de Heem has created some added interest by including representations of the pests that will before too long put an end to all that beauty. The 'still life' has actually quite a lot of life in it that is very much on the move. But for the moment at least the flowers are undamaged.

The morbid may reflect on the fact that these beautiful flowers are already merely corpses on life-support, but for the moment we see no trace of that ruin. But the man who painted that also painted this:

Jan Davidszoon de Heem, Stillleben mit Vogelnest, post 1670. Image: Wikimedia.[1]

[Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab, 2014 x 2540 px.]

In such cases there is no one quite like a Freud-era German psychoanalyst to clear this problem up for us. The job was tackled by Georg Walther Groddeck (1866-1934) in 1933, in a pamphlet called Der Mensch als Symbol, 'Man as Symbol', published by the Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag in Vienna. The German text is available online.

On Dr Groddeck's couch

Here is Groddeck's analysis in English[2]

On the far right of the picture we see a tree. Around its trunk a branch has wound itself. Both of them, trunk and branch, are dotted with playful hints, the description of which could occupy us for a long time.

In particular we can see two faces: one, with a broad nose and a laughing mouth, is formed from a scarred wound in the trunk; close by it there is an ape-like face to be seen at the end of a stump. These faces give us a clue to the way we have to look at the whole painting.

Hunger, love, life, death appear in many different guises. A colourful bird perches at the top of the painting with open wings, while his/her partner lies dead on the ground.

Between the two birds, but in proximity to death, we see a nest. It contains two eggs; a third egg is broken in two halves, but the yolk has not run out. On a stalk sticking out of the nest a butterfly stands, its wings half folded. The butterfly is separated from a caterpillar by a bent corn stalk.

This stalk also separates the dead bird from the nest and the broken egg. Further up it ends at an oak twig with two acorns and an empty acorn cup.

In order to complete the parallel, the ear of an upright second stalk points towards a forked twig, while the ear of the bent stalk, along with another ear, points towards the ground.

The number three appears in the arrangement of the three twigs of the oak cluster, one part of which lifts up like a phallus; on its furthest point a colourful butterfly with widespread wings is perched, full of lust for love and life.

On the branch that wraps itself around the tree a cockchafer is crawling along, a symbol of the sex drive in its most brutal form. All children have got excited over its unambiguous lust for sex. Further towards the righthand edge a stag beetle can be seen, doubly symbolic of man and woman in body and mandibles.

Translator's note: 'The sex drive in its most brutal form': after a four year development cycle the mature cockchafers breed, which is the only purpose to their existence. The males die after copulation, the females after laying their eggs. Stag beetles are sexually dimorphic, that is their bodily form differs between males (large mandibles) and females (small mandibles).

And, quite hidden, murder creeps: from the fork of the twig towards which the ear of corn is pointing a spider is lowering itself onto a mosquito. However, not far away a gall wasp is on an oak leaf, bringing life into the world.

A snail marvels at all this tumult of life and death, love and procreation, as it, doubly symbolic, strains upwards to feed.

Here a gourd pokes its stem up in the air, there a fly refreshes itself on the juice that has collected in a split in the melon. One sees caterpillars and millipedes, the doubly symbolic dragonfly, the voracious grasshopper, burst chestnuts as symbols of ejaculation and birth, mouse and salamander, frog and beetle. As one fly gorges on the split in the melon, a second, smaller one is enjoying itself on that symbol of the backside, the peach.

But on the left edge there are two thistles, which point upwards with their flowers towards a hole in the vault of the crumbling stonework.

There is so much going on in this painting that we might wonder whether it really should be classified as a 'still life'. Groddeck remarks:

The large number of symbols make it probable that in this still life de Heem was intentionally telling the story of life, love and death.

In his essay Groddeck also draws our attention to another 'fruit and bird's nest' painting from the same era, a remarkably similar still life done by Abraham Mignon (1640-1779) Ein Vogelnest im Fruchtkorb, 'A Bird's Nest in a Basket of Fruit'.

Abraham Mignon: the impending disaster

Similar in many ways, but really competely different in intention, Mignon's painting contains many of the same objects as de Heems, but is not laden with such a quantity of symbolism. There is nothing of de Heem's death motifs in Mignon's painting. The comparison is particularly remarkable, since Mignon studied under de Heem or was his follower at Utrecht for a number of years.

Abraham Mignon (1640-1679), Ein Vogelnest im Fruchtkorb, ND. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Dresden.

Many of the ingredients in de Heem's painting are also present in Mignon's piece.

The trunk of the tree and the winding branch, the arched stonework in the background, the two birds (both, however, alive), the grapes, white and red, the gourd, the melon, the open chestnut, the peaches, the plums, the vine leaves and the corn stalks, the thistles, the coloured butterfly and the white moth on a vine leaf, the bird's nest with three eggs, even the cockchafer, the gall wasp (but on a vine leaf) and the snail are present.

There are some differences, but surprisingly few: Mignon shows us a quince (N.B. traditionally the fruit of Venus), a thistle gone to seed, the structural element of the handle of a basket; missing are the stag beetle, the murderous spider, the oak leaves, the acorns and the faces in the tree.

We note that the fruits in Mignon's still life are not perfect – most have been damaged, nibbled or attacked in some way. We also note that the structural principle of Mignon's painting is the rough vertical golden-section line that runs from the topmost bird, through the second bird, through the nest and down to the peaches and the quince.

However, we note that Mignon's picture also steps back from the perfection of the classic still life of the time. Most of the fruit he depicts has been damaged in some way and there is much future damage to be expected from the many predators he also depicts. This impending destruction is not fanciful: right at the top centre of his painting we see a rain of newly-hatched caterpillars or maggots falling down from a rolled-up leaf, the underside of which is unmissably bright. The rolled up leaf is just as much a nest as the bird's nest and its progeny now litter the ground at the base of the composition – yet another source of potential destruction for the fruit. The maggots have their own predator though: the bird resting on the handle is pointing not just at the nest but also at the helpless maggots on the ground.

Jan Davidszoon de Heem and Abraham Mignon

There must be a relationship between the creation of these two paintings, they have too much in common. They were painted by collaborators in the same town. It is barely conceivable that Mignon painted his as a response to de Heem's: how could anyone start with de Heem's symbolic wilderness and make something much glossier and more superficial out of it? That would be going backwards.

It appears that de Heem took one further step from Mignon's painting in order to show us a similar scene that we might see a week or two later. For example, all that now remains of the luscious berries we saw in Mignon's picture are a few left-overs almost outside the scene. It seems more likely that for whatever reason, de Heem took Mignon's painting, which was suffused with the potential for decay and death, and took it the next step by extending the life-death, sex-death axes. Why? No idea.

In Groddeck's reading of de Heem's painting there is a lot of emphasis on allegorical meanings derived from structure of the image – the ear of corn that points at the forked twig, or the structural effect of the long corn stalk. Not all of Groddeck's psychoanalytical suggestions are fully convincing, but he has made a sound case for the existence of symbols and allegory in the work. He also reads some gender symbolism into the odd numbers in Mignon's painting, clusters of three, five and seven, but a less abstruse reason seems more likely: odd numbers are traditional as compositional elements – they just look better, that's all.

What prompted de Heem to produce his gruesome work? Who paid for it? Mignon died young, 35 years old, de Heem outlived him by around four years and died at a fine old age for the time of around 78 years old. Was his death-suffused painting an homage to his young follower in Utrecht? Or mortality in his own family (de Heem had a large family by two wives)? No idea.

Sniffing the Easter cake

Now we have cleared that up, let's say farewell to Dr Groddeck with some more ponderings of his on the subject of birth, life and death, cakes and excrement.

A meditation that is perfect for Easter, a time when we celebrate the cycle of death, decay and rebirth, but packaged in our modern insulated and sanitised civilisation in the form of Easter eggs, Easter chicks and that sex fiend, the Easter bunny. Cake baking is an Easter tradition, too – most Christian countries have their specialities of the season. Our learned Doctor Groddeck can help us here, too.

For me it is clear that the oldest kitchen in the world is the belly, specially the female belly with the cooking pot being the uterus and the fireplace the vagina, and that the first cook was a man, who lit the fire and with the help of his symbolic commis chef made the woman pregnant.

And this commis chef is called in French coq (coquet, coquin) und in English cock, in German Gockler, und in Latin 'cooking' is called coqueo.

Coq, 'cock', the word for the male genitalia, is also called Hahn, 'cock'. Hahn is also that animal with coxcomb and spur, the name coq also designates the genitalia, and in Swedish it is called han he, hun (written 'hon') she, hennes her. That is the state of affairs. The Hühnchen, 'chicken' is Küchlein, the Küche, 'kitchen' is Kuchel (English chicken and kitchen).

And placenta is the Greek word plakus and the German word Fladen, both of them words for Kuchen, 'cake', and in Swedish Kuchen, 'cake' is kaka, and while the German says Kuhfladen, 'cowpat' the Swede says for the same thing kokaka.

And kacken, 'to shit'? No, this is going too far. This is no longer decent.

But it is true. If in your bowels, this excellent Küche, 'kitchen', you miserable humans did not have millions of microbes, you would soon be finished. They bake the cake that the rough barbarian calls Kacke, 'shit', and the microbes of the sperm bake the Mutterkuchen, 'placenta', and symbolically – that has been proven long ago – birth and excretion, baby and excrement are the same (atavism?). Yes, it is indelicate, but it is true.

Humans have an insatiable appetite for indecent things – I will therefore continue. The Henne, 'hen', lays eggs, that means in the nature of things she excretes these eggs and gackelt, 'clucks'. Kackeln and kakern are other expressions for this. In Greek the partridge is called kakkabe (κακκαβη) and kukkazo (κακκαζω) = gackern, 'to cluck', kakkao (κακκαω) = kacken, 'to shit', kakke (κακκη) is identical to our German word [Kacke, 'shit'].

Georg Groddeck, Der Mensch als Symbol, p. 7.

There you are, you see. It's all just a load of crap, in other words.

The Georg Groddeck Society

If your curiosity about the good doctor has been piqued you will find much of interest (in English and German) on the website of the Georg Groddeck Society.

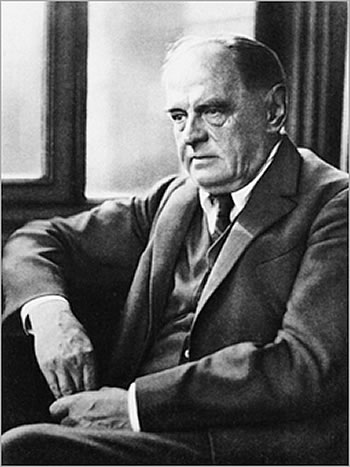

Dr Georg Groddeck in 1933, one year before his death. Image: ©Georg Groddeck Society.

References

-

^

De Heem's Stillleben mit Vogelnest is in the possession of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden. Although de Heem has been dead well over 300 years the Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden is sitting tight on its possessions. We sent an email request for a high resolution version of this work. After a couple of days' thinking time, for an image half the size of the Wikimedia image they demanded a 20 EUR processing fee and a further 80 EUR reproduction fee per instance for a duration not exceeding five years – far too much for an inferior product on a free blog. The gallery's possessions were paid for and amortised in previous generations and their current existence is heavily subsidised by the taxpayer. Their website shows only small images from their collection, which in the case of de Heem's detailed painting is self-defeating.

Compare this with the excellent Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, who have opened out their wonderful collection and made reproductions easily available for download and unrestricted free use. - ^ All translations ©Figures of Speech. Please link to this page when quoting.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!