23 May 1618: the Second Defenestration of Prague

Richard Law, UTC 2018-05-30 08:12

The Second Defenestration of Prague was a remarkable event, made more remarkable for being the trigger that initiated the epochal disaster that was the Thirty Years' War.

The defenestration by Václav Brožík (1851-1901), c. 1889. Image: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

The gathering storm

Among the horrors of history, the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) is a strong contender in a packed field for the dubious honour of being the most horrible. Despite this, little is known about it outside the continent of Europe – the details of all its participants and all its battles are even more mindboggling for the non-specialist than the average European conflict.

Many factors came together to make the war particularly gruesome, but the three most important in this case were weather, politics and religion.

The weather of this period is now famed as being around the deepest point of the Little Ice Age: cold, long winters and mediocre summers in unremitting sequence. There were frequent crop failures throughout Europe and starvation was the ever-present companion of the common people. Arising from starvation and malnutrition, plague and disease flourished in weakened bodies.

The politics of the period resemble the contents of a hot pressure cooker when the lid is removed too quickly: within a short space of time the great and small powers of Europe set about each other. The Habsburg Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and the old enemy Bourbon France seized their chance to struggle for European dominance. Ultimately Austria, Spain, France, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden were all hacking each other about in fluid alliances.

As if this were not enough political violence, historians identify three other smaller wars rumbling around that were embedded in the great conflict: the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648) that had already been festering for forty years between the Netherlands and Spain, the French-Spanish War (1635-1659) that ran on eleven years after the Thirty Years' War had finished and the Torstensson War (1643-1645) between Sweden and Denmark.

The pressure cooker of religion also played its part –some historians think religion played the major part. Almost exactly a hundred years before, on 31 October 1517, Martin Luther had sent his Ninety-Five Theses to the Archbishop of Mainz, triggering the Protestant Reformation.

In those hundred years, religious schisms spread inexorably throughout Europe. When the political pressure cooker boiled over, Europe was already deeply and bitterly divided along religious lines.

It is not a new observation, but there is nothing that brings barbarity and bloodlust out in people quite like Christian goodwill to all men. The Protestant Reformation led to the Catholic Counter-Reformation and the Inquisition. Many on all sides died horrible deaths having their souls saved for them.

The name Thirty Years' War tells us: the slaughter went on for thirty years, only coming to an end when Europe staggered, exhausted, into the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

When the nations finally stopped massacring each others' people the scholars of the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightement could pick up where they had left off and a great – albeit imperfect – age of human progress in central Europe commenced. It took some time, though, before the weather started to get better.

Creating a crisis

The Second Defenestration of Prague removed the lids of the political and religious pressure cookers. The First and the Third Defenestrations don't concern us at the moment – they were also consequential, but nothing like as much as the Second Defenestration. They were also well outside the period.

We know from many, many historical examples, that the best way to foment unrest is to grant a freedom and then take it back. In 1609 Rudolf II (1552–1612), Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia granted additional rights to Protestants in Bohemia. Within the fundamentally Catholic Holy Roman Empire Rudolf II's generosity to the Bohemian Protestants was not unopposed.

Kaiser Rudolph II (1552-1612) by Joseph Heintz the Elder (1564-1609), 1594. Note that on the chain around his neck he is wearing the great, primarily Catholic order, the Order of the Golden Fleece.

His younger brother Matthias (1557-1619) succeeded to the throne upon Rudolf's death in 1612 and went even further in granting Protestants in Bohemia political and religious freedoms.

Kaiser Matthias (1557-1619) by Lucas van Valckenborch (1535-1597), 1583.

Matthias, close to death, had his cousin Ferdinand of Styria (1578-1637) elected king in 1617. He became Ferdinand II. Unlike Rudolf and Matthias, Ferdinand was a Catholic bigot of the first order – dim, Jesuit-educated, pious beyond measure – just the man to force open the lid of a pressure cooker. Under his rule there would be no compromise with heretics.

Kaiser Ferdinand II (1578-1637), artist unknown, c. 1614. Ferdinand is wearing the armour of his grandfather Ferdinand I (1503-1564), from whom he also inherited his fine Habsburg lip. He is also displaying the Order of the Golden Fleece on the great chain – as with Rudolph in his portrait, it is the only piece of bling he feels he needs to wear.

Up to then, peace between the religious factions had been kept by allowing the local ruler his choice of religion. Despite the local support for Protestantism in Bohemia, Ferdinand started to block its development there. He pulled down one Protestant church and closed another. When the Bohemian Assembly protested at this interference, he dissolved it.

Chucking out time in Prague

On 23 May 1618, at eight-thirty in the morning, four Catholic nobles, Ferdinand's emissaries, arrived at the Bohemian Chancellory in Prague Castle with a letter from the King. Instead of an orderly Assembly meeting, around 200 Protestant nobles turned up, quite a few of them in their cups, even at that time in the morning. A 'mob' is probably the right word for the gathering.

Prague Castle, showing A) the Royal Castle, B) the Chancellory building 'from which the three Imperial Councillors were thrown' and C) the deer park. Published 1627. Image: Wahre Contrafactur wie die Kays. Räthe zum Fenster hinaus geworffen worden seindt.

Ferdinand's letter was read out. Its contents were so inflammatory and dismissive – essentially Ferdinand threatened the Bohemians with confiscation of their property and death without further ado – that the mob was unsurprisingly outraged. Ferdinand reminded his underlings of their feudal duty to obey him, their feudal master – hardly a recipe for winning hearts and minds.

The defenestration in an engraving by Matthäus Merian (1593-1650), ND but not contemporary.

The mob wanted to know whether Ferdinand's nobles were just expensive messengers or party to its writing. Two of the four were exonerated as being too wimpish to be in involved in the creation of such an arrogant letter, the other two, Count Wilhelm Slawata and Count Jaroslaw Borsita, along with their secretary Philipp Fabricius were known to be fanatics for the Catholic cause.

Interior view of the Chancellory and the windows from which the emissaries were thrown. Image: Charli 30.05.2013.

Under questioning they foolishly admitted that they bore some responsibility for the contents of the letter. The mob decided to send an urgently impressive message back to Ferdinand: they threw his three representatives out of the window. Defenestration being, we are told, an old Bohemian tradition.

Prague Castle, showing the Chancellory room on the second floor.

The drop was about seventeen metres from the window down to the bottom of the dry moat. All three of them survived without serious injury, the worst off being Count Slavata, who had held on to the windowsill until his attackers bashed his fingers bloody. He tells us that when he finally let go, during his descent he bounced off the sill of the lowest window and hit his head on a stone on landing. Philipp Fabricius was the last one to be thrown out. He too landed relatively intact.

The fact that all three survived the defenestration without serious injury has been a cause for speculation. It seems most likely that because the wall under that window is not vertical but slopes slightly, their descent would have been more like a slither than a plummet. They were all wearing heavy cloaks that cushioned the impact and the descent on to the sloping sides of the dry moat was more rolling than falling. The window was relatively small and a bit of resistance on the part of the victims meant that they could not be hurled far out.

The defenestration in a woodcut from a leaflet of 1618.

The widespread legend that they fell on a dung heap that cushioned their landings has no contemporary source and is probably just that, a nice propaganda legend. The presence of a dung heap directly underneath the windows of the Chancellory seems odd. None of the defenestrated mentions landing on a compost or dung heap. Historians therefore suspect that the story about the dung heap was the Protestant answer to the Catholic explanation of their miraculous survival, that the angels and/or the Virgin Mary had intervened to break their fall.

After landing, the three were physically and mentally intact enough to take flight down the road. When the mob upstairs noticed that their defenestrated victims were now running away they pulled out their pistols and opened fire. The narrowness of the windows appears to have saved the three yet again: 17th century pistols were useless at a distance, especially when fired by enraged drunks jostling for position at the narrow windows.

The three defenestrated emissaries were taken in and protected by a Catholic noblewoman, Polyxena von Lobkowicz, whose castle was also part of the large complex of buildings on the Prague Castle site, not far away from the Chancellory. One of the two emissaries released before the defenestration was a Lobkowicz, so news would probably have reached Polyxena quickly.

Polyxena von Lobkowicz (1566-1642) protecting the emissaries after their escape. The angry mob is on the left, the injured emissaries are being tended in the room behind her. Painting by Václav Brožík (1851-1901), unknown date.

Revenge – a dish eaten cold

The defenestration of his emissaries was not just a rebuff to Ferdinand, it was an insult and a challenge. Ferdinand bided his time – he had tasks closer to home. His uncle Matthias died in the following year without issue and he, Matthias' designated successor, was duly elected Holy Roman Emperor.

During this time the Bohemian Protestant nobles formed their own aristocratic rule in the country. On Ferdinand's accession, they illegally and disrespectfully deposed him as King of Bohemia and replaced him with a Protestant, Frederick V. A year of diplomatic manoeuvring followed as both sides collected allies, Ferdinand more successfully than the Bohemians.

Kurfürst Friedrich V. von der Pfalz (1596-1632) thought to be by Michiel van Miereveld (1567-1641), c. 1625.

These efforts culminated in the Battle of White Mountain on 8 November 1620 between the Catholic Imperial Army (Austrians and Bavarians) and the forces of Protestant Bohemia. The 13,000 Bohemian Protestants were outnumbered by three to one and lost nearly thirty percent of their army; the Catholic losses were trivial in comparison.

Following the battle the Imperial forces entered Prague. Frederick V fled with barely the clothes on his back. The moment of Catholic revenge for the defenestration and all that had followed it had come.

Sixty-one of the leaders of the Protestant revolt were arrested. Twenty-seven of them, the principal aristocrats, were executed in Prague on 21 June 1621, their land and possessions confiscated and redistributed to the loyal Catholics. One of the loyal Catholic beneficiaries was Polyxena von Lobkowicz, the woman who had sheltered the three defenestrated emissaries. Her family profited greatly from the extensive properties they were granted.

Twelve of the executed had their heads impaled on iron spikes hung from the tower of the Old Bridge in Prague.

The execution of the Bohemian rebels on the Altstädter Ring in Prague on 21 June 1621. The style of the exucutions was in accordance with the feudal rank of the victims: on the platform kneeling in front of the crucifix with a horizontal swipe of the sword; top right suspended for a gallows; there seems to be a firing squad, too. The bloody mess on the chopping block is Count von Schlick's right hand, which was chopped off and nailed onto a tower of what is now known as the Karlsbrücke in Prague. He had been one of the leaders of the rebels.

Bad enough as the result was for the Protestant nobles, it was terrible for the Protestants among the common people in Bohemia. Many tens of thousands – who knows how many, some say thirty, some forty thousand – were killed or driven out or fled, their possessions confiscated. Most fled to Germany, a migration that in turn helped to shape the Protestant character of north-eastern Germany.

In the lands of the Holy Roman Empire the pogrom against Protestants would continue with varying intensity for more than a century and a half. Even the great Maria Theresia was an enthusiastic persecutor of Protestants, as was her 'enlightened' son, Joseph II, when it suited him.

If readers visit the great Catholic cathedrals and monasteries of eastern Europe they should reflect on the pogroms and religious cleansing of the Thirty Years' War that ultimately secured the dominance of Catholicism there.

The Battle of White Mountain is considered to be the first of the many engagements of the Thirty Years' War. The battle and what followed it set the brutal tone for everything that followed in the subsequent twenty-eight years.

The war takes its course

Every November in modern times, Europeans recoil at the memory of what happened to men's bodies in the meatgrinder of the military-industrial complex during the First World War.

In the Thirty Year's War things were different – you hacked, shot, clubbed and skewered your opponents face to face, looking them in the eye. The great King of Sweden, Gustavus Adolphus (1594-1632,), already injured, strayed from his troops in the Battle of Lützen, near Leipzig in Saxony on 6 November 1632 and was hacked down and shot to death on the spot.

'What', you may ask, 'was the King of Sweden doing in German Saxony?' and with that question you have hit on the European and religious dimension of the war. Gustavus was a Protestant helping out the German Protestants against the Catholic Imperial army under Albrecht von Wallenstein.

Gustavus was there as a result of a catastrophic error that Ferdinand II had made in 1629. Up until then the war had largely been going the Catholics' way.

Buoyed by all this apparent success, Ferdinand issued his 'Edict of Restitution', intended to clean out Protestantism completely. Only a dim, authoritarian, religious bigot of the calibre of Ferdinand would believe that such a measure would bring peace to Europe. It was that which got the Swedes involved, an event which, in turn, became the turning point for Protestant fortunes.

In the years after the death of Gustavus Adolphus in 1632 the tide turned and the Protestant side became dominant. Ferdinand II died in 1637 and was succeeded by his son Ferdinand III (1608-1657), whose destiny was to experience the Habsburg setbacks one after the other.

The meatgrinder grinds to a halt

It would be nice to say that the Thirty Years' War came to an end as an outbreak of humanity and reason descended upon Europe. That would be far too much to expect – the warring parties simply ran out of money. The basic economic condition of central Europe could no longer be ignored: the collapse of the population, of agriculture and human prductivity.

Whatever disasters nature and weather left unfinished, war completed. The population collapsed, crops were pillaged and no farm was safe from the marauding armies living off the land. Hundreds of thousands were massacred, of those left alive whole populations were driven out as refugees. More starvation, more disease, more death. The Four Horsemen thundered here and there across Europe and laid it waste.

Historians now estimate that in the German Habsburg Empire alone there were five million deaths – that is, one fifth of the population. Although some areas escaped serious damage, there were others which suffered terribly. Bavaria lost nearly half of its population. Most died not from the direct effects of warfare, but from hunger and epidemics: the consequences of bad seasons, the loss of agricultural labour and land left unworked. When a hungry army passed over your land or quartered itself upon you, crops, seed corn, livestock and stores were all consumed or pillaged.

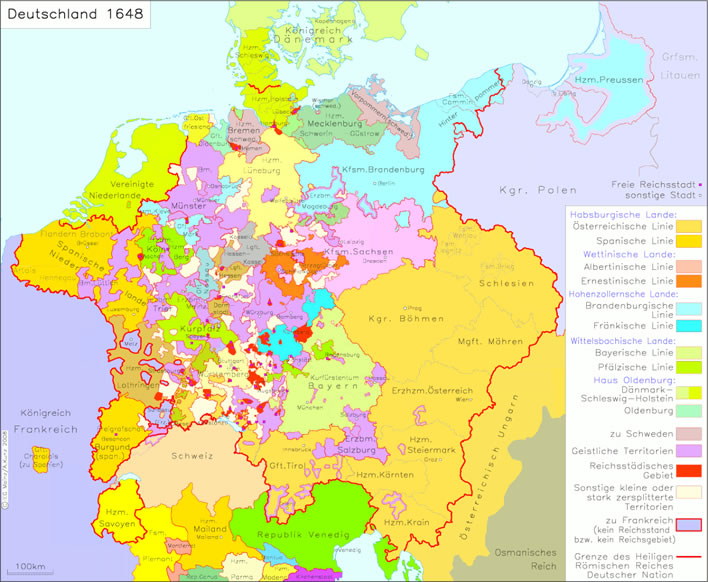

In 1648 a treaty was reached: the Treaty of Westphalia. It is a remarkable agreement, in which the fighting in Europe came to a standstill, leaving Germany as a patchwork of small fiefdoms.

Map of the European patchwork that came into being after the conclusion of the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. Image: IEG-Maps, Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte Mainz, ISSN 1614-6352.

It resolved nothing really, but at least it stopped most of the killing. One hundred and fifty years later, Napoleon did his best to redraw the map of Europe that the Treaty of Westphalia had left behind, but the completion of that task was finally left to the Austrians, the Prussians and the French – and we all know how that turned out, don't we?

Amongst all this gloom and misery let's try and end on a more cheerful note. For the art lover the period represents yet one more example of the fatuous and oft-quoted historical paradox inserted by Orson Welles into the film The Third Man: great artists seem to flourish when political turmoil is at its worst. As proof of his paradox Welles had his character Harry Lime, the wartime racketeer, invoke the Italy of the quattrocento – its high culture combined with the gangsterism and corruption of its great city states.

In respect of the Thirty Years' War, we could also list a selection of the artistic giants who flourished whilst that conflict rumbled on: Bernini, Breughel the Younger, Bronzino, Caravaggio, van Dyck, Franz Hals, Nicolas Poussin, Rembrandt, Rubens, Tintoretto, Valazquez and so on and so on.

However, the reader will note that these artists were all active on the outer margins of Europe, well away from the turmoil at its centre. Central Europe was not a good place to be during those times, the times that started with the Second Defenestration of Prague.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!