Image of the month 06.2018

Richard Law, UTC 2018-06-10 11:07

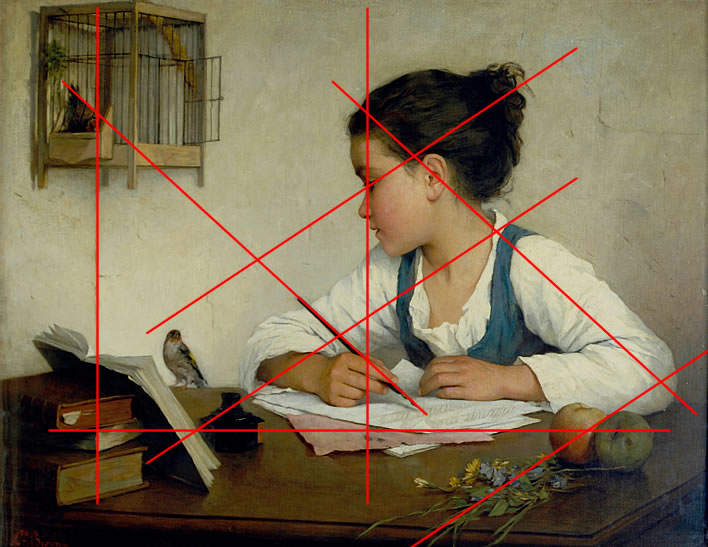

Henriette Browne (Mme Jules de Saux, née Sophie Boutellier) (1829-1901): Enfant écrivant / A Girl Writing / The Pet Goldfinch, c. 1870. Image: Victoria and Albert Museum. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab, 3137 x 2422 px]

This painting is part of the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Unfortunately, the V&A is one of those museums/galleries that restrict internet access to quality images of their paintings. The image of this painting on their website has been deliberately faded. The image offered for download is larger, but just as bad in detail and colour rendering. The image is also available from Google Arts and Culture, but in a gloomy and unappealing reproduction.

This painting was displayed on the Figures of Speech homepage for a few months until recently. It didn't really deserve this dismissive treatment, so before we leave it behind for ever after the recent redesign of the site, we thought we would give it a worthy send off.

The hurrying passer-by would acknowledge its great charm – but that charm itself makes the modern person uneasily think of chocolate-box lids (do we still have those?) or the contemptuous German word Kitsch.

In fact, this is a very fine painting in every respect – in composition, concept and execution – the fact that its creator is a woman should make it even more worthy of attention in these female-boosting days. The case is indeed a strange one: among her works that have come down to us there is nothing else that is anything like this painting.

Firstly, the composition. We can assert without fear of contradiction that the composition of a painting is a success when the viewer never notices it. In this case the balance of the elements is so perfect we never think to start measuring golden sections and hunting for alignments between the various elements.

There is one unfortunate compositional feature: in order to obtain the satisfying vertical alignment between the birdcage in the corner of the room and the bird and the stack of books below it, the back corner of the table is obscured by the books. This means that the observer has no perspective understanding of the back wall – we worry where the space comes from between the back of the table and the wall behind it. The edge of the top book creates an optical illusion that allows no space for the girl to sit. Once you clear that optical illusion out of your brain the perspective works perfectly: the birdcage is not above but behind the table.

Telling the tale

We have to read this painting as a narrative, not as a still life or a simple genre painting.

The girl is young – seven or eight years old, perhaps. She is practising her writing on ruled sheets. The girl's hair is bound up to keep it out of the way of her work. We might care to think that it flowed loose and unfettered in the fields outside.

The schoolbook is propped up in front of her on a stack of substantial books, one of which at least already has a marker paper in it. Our ancestors, brought up in the allegorical language of paintings, would immediately grasp the metaphor of the pile of learning that awaits behind that school exercise book. The girl is just at the start of this journey.

The handful of wild flowers on the table and the fruit behind tell us that shortly before, the girl had been running free outside. She picked the wild flowers and the fruit and brought them back with her to her session of confined labour at the writing table. The flowers from the outer, natural world now lie wilting. There are two different fruits, hinting that she has roamed some distance.

Seventeenth-century eyes would see metaphors of future fecundity whenever girls were juxtaposed with fruit and flowers. But the routine metaphor does not apply in this painting: the flowers are wilting and the fruit is rendered with all its flaws. These elements do not represent fecundity but are the symbols of the natural, free-running world outside the door, objects that now dessicate in the dry world of learning on the writing table.

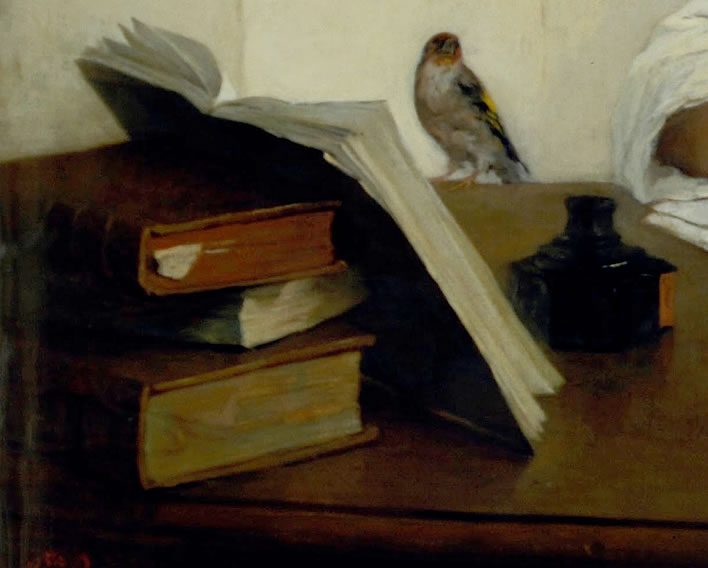

The girl's eye is in the horizontal centre and the vertical golden section of the painting. It is thus the most compositionally important element. She is gazing at the goldfinch perched on the desk alongside her. The bird shows no fear – in fact, the two almost appear to be talking to each other. The bird seems to be singing, but because of the miserable quality of this reproduction we cannot be sure.

Their situations are reversed. The goldfinch has been released from its cage and is, for the duration of her homework, free, albeit with restrictions. The girl, in a sense, has returned to her cage from her brief period of freedom outside. In the cage, the bird is a prisoner who is fed and watered and cared for. In her house, at the writing table, we may think of the human prisoner who is fed and watered and cared for.

If we look closely at the cage we see that the goldfinch on the table has a companion who is currently in the cage feeding from the little trough. There is also a sprig of some kind of greenery in the cage, perhaps an analogue to the flowers on the girl's table.

Everywhere in this painting there are hints and metaphors aplenty for those with eyes to see and time to stare: the transition from the world of nature to the world of human culture, from childhood to adulthood, from freedom to imprisonment – even the choice of voluntary imprisonment.

Really not at all the kind of thing you want to see on a chocolate box lid.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!