The Poets' War

Richard Law, UTC 2018-09-30 22:32

The free spirits that alight on this website may find all this graph drawing a bit dry. Let's look instead at a contemporary case of the treatment of homosexual acts in practice. For our purposes no better example exists than the confrontation between the two writers, Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) and Count August von Platen (1796-1835) in what some excitable people call the Poetenkrieg, the 'Poets' War', that broke out between the two in 1827.

Bruchmann, Senn, Platen and the Schubert circle

Platen will be known to a few Schubert fans as a figure on the periphery of the circle. He was primarily a friend of Franz von Bruchmann (1798-1867). Schubert set a few of Platen's technically very finished poems to music (e.g. in 1822 Die Liebe hat verlogen, D 751).

Since Platen most definitely had homosexual proclivities, let us take a moment to look at the relationships between him and the Schubert circles of friends. Bruchmann had been a close friend of Schubert and Johann Senn. He was even caught up in the arrest of Senn that took place around 24 March 1820. Senn was kept under police arrest for nearly a year and then exiled. The police reported Bruchmann's involvement in the turmoil of Senn's arrest to Bruchmann's father.

Bruchmann met Platen in 1821 when he attended the University of Erlangen to listen to Friedrich Schelling's lectures. Bruchmann's study trip to Erlangen was illegal: in an attempt to stop the unrest of the time among German students spreading into Austria, Austrian citizens were not allowed to attend university courses outside Austria without special permission. That fear of student rebellion lay behind the arrest and disgraceful treatment of Senn, but neither that, nor the measures taken against Bruchmann personally seem to have intimidated him. This bravery alone should earn our respect.

Bruchmann intervened in 1823 to extricate his sister Justine from a 'secret engagement' with the reprobate Franz Schober. This caused a split among the friends. After 1825 the split amongst the Schubert tribe never really healed, some taking Bruchmann's side, others (the inner Schubert circle) Schober's.

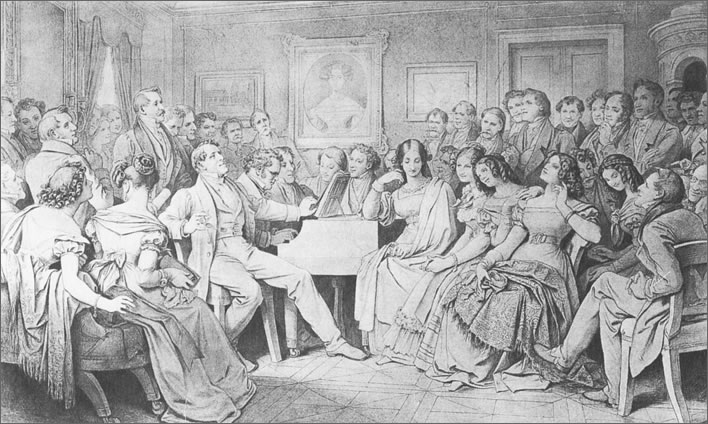

Moritz von Schwind's homage to a Schubertiade. This was drawn in 1868, 40 years after Schubert had died, and is therefore not a portrait of any particular event but more of a group portrait of the people in Schubert's life.

As we noted in a previous piece: in the second row on the right of the picture Franz von Schober is flirting with Justina von Bruchmann. They are the only ones not listening to the performance. Schwind is reminding us that Schober entered into a secret engagement with Justina (whose father was probably the richest man in Vienna). This plan was discovered and the engagement dissolved in 1823, leading to a break between Schober and her brother Franz von Bruchmann, a leading figure in the Schubert circles. By the time he created this group portrait Schwind had himself developed a deep loathing for Schober, a loathing that is unmistakeably revealed. Revenge is a dish that needs to cool for 40 years before it is eaten.

As already mentioned, Franz Bruchmann had also been one of those most closely caught up in the arrest of Johann Senn. As far as we know only Bruchmann visited Senn in exile in Innsbruck, which he did first in 1822. [Dok 162] This visit was another act of courage and/or wilful defiance on Bruchmann's part, since Senn was under the continuous surveillance of the secret police in Tyrol. Bruchmann kept in correspondence with Senn using a proxy address for several years. Another figure from the Schubert circle, Moritz Schwind, also kept in touch with Senn during his exile and visited him in 1830.

By mid-1826 Bruchmann had embraced Christianity with the same single-minded dedication with which he had once embraced revolutionary politics, philosophy and art. The rest of his life would be spent as a Redemptorist priest, in which calling he followed a substantial career in the church. It would take a wild imagination to construe either Bruchmann or Senn as being partial to homosexual activities.

On this point, there are those who suggest (on no evidence whatosoever) that Senn's year or so in police arrest was actually a criminal sentence for sodomitic practices and had little or nothing to do with political activism. [Dürhammer 202] We shake our heads wearily. It is surely only a matter of time before someone interprets the beatings given to the refractory Senn to encourage him to spill the details of whatever Jacobin student conspiracy he had been involved in as really only some sadomasochistic game that Senn was playing with his unwitting captors.

Bruchmann and Senn fell out around 1835 (it may have been a few years earlier). In his bitterness at his poverty-stricken life in exile Senn had become more and more isolated. In contrast, Bruchmann had become ever more successful within the church and the hortatory, redemptorist tone of his letters seems to have grated on Senn. Senn's fiery, youthful promise had been sabotaged by the police action and the restrictive terms of his exile – even in exile he was kept under continued observation and all his post read.

Platen was always a very peripheral member of the Schubert circles – Otto Deutsch does not bother to list him in the 'Personalien' section of Dokumente[Dok 605] It is suggestive, though not dispositive, that the undoubtably homosexually inclined Platen kept his distance from the putative 'homosexual subculture' of the circles of friends. If there was a raging homosexual or bisexual subculture among the friends, it certainly didn't appeal to Platen.

Platen the antisemite, Heine the Jew

The Poets' War is considered to have damaged both of the participants: Heine lost the chance of a professorship in Munich, Platen exiled himself to Italy, being unable to rejoin polite German society after what Heine did to him.

It was Heine who, in 1827, fired the first, relatively harmless shot in the war. In an appendix to his Reisebilder. Zweiter Teil (1827) he reproduced some couplets by Karl Lebrecht Immermann, which mocked the then fad for orientalism among German poets, of whom Platen was one. It was literary mockery – not kind, but not personal.

Platen took offence and shot back in 1829 in his comedy Der romantische Ödipus with a vicious antisemitic attack on Heine, the 'pride of the Synagogue', whose 'kisses gave off the stench of garlic'.

Heine, born Harry Heine, had converted to Christianity in 1825. It was a step he would later deeply regret – the conversion brought him no advantage and alienated him from the Jewish heritage he respected.

In reading Platen's words Heine now experienced the same antisemitism that would drive the Austrian journalist Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) to found the Zionist movement at the end of the 19th-century: there was no level of integration, no level of education, no level of social success or service to the state that insulated Jews from antisemitism – once a Jew, always a Jew.

For Heine, it must have appeared to be impossible to have a literary argument without his Jewish origins being fielded against him. Herzl went on to prepare the foundations of a Jewish homeland in Palestine; Heine coped with antisemitism in various ways, one of them was destroying Platen's reputation in his Reisebilder. Dritter Theil. Die Bäder von Lukka, Capitel XI, published in 1830.

Getting to the bottom of Platen the sodomite

Heine was the master satirist of his time and hit back at Platen's homosexual behaviour. Of course, as we now know, Heine did not have the word 'homosexual' in his vocabulary, so the style and content of his attack gives us an insight into the attitudes of the time towards homosexual behaviour.

He is no poet, say the ungrateful male youths of whom he so tenderly sings. He is no poet, say the women, who perhaps – I have to hint at it as positively as I can – are not so unbiased and perhaps because of the devotion [to young men] which they sense in him experience some jealousy, or even through the tendency of his poems to threaten their advantageous position in society.

Strict critics, who are equipped with good spectacles, agree with this judgment or express their concerns even more briefly. What do you find in the poems of the Count von Platen-Hallermünde?, I recently asked such a man. Buttocks! was the answer. You mean in respect of the arduously worked out form?, I replied. No, this person responded, buttocks also in respect of the content.

Er ist kein Dichter, sagt sogar die undankbare männliche Jugend, die er so zärtlich besingt. Er ist kein Dichter, sagen die Frauen, die vielleicht – ich muß es zu seinem Besten andeuten – hier nicht ganz unpartheyisch sind, und vielleicht wegen der Hingebung, die sie bey ihm entdecken, etwas Eifersucht empfinden, oder gar durch die Tendenz seiner Gedichte ihre bisherige vortheilhafte Stellung in der Gesellschaft gefährdet glauben.

Strenge Kritiker, die mit scharfen Brillen versehen sind, stimmen ein in dieses Urtheil, oder äußern sich noch lakonisch bedenklicher. Was finden Sie in den Gedichten des Grafen von Platen Hallermünde? frug ich jüngst einen solchen Mann. Sitzfleisch! war die Antwort. Sie meinen in Hinsicht der mühsamen, ausgearbeiteten Form? entgegnete ich. Nein, erwiederte jener, Sitzfleisch auch in Betreff des Inhalts.

[Heine 139]

Here, a satirical construction that is typical for Heine pushes your translator to the limits of his skill: Sitzfleisch, literally 'bottom-meat', is a joking metaphor used in German for 'plodding stamina, drudgery' – the stuff that compiles dictionaries and railway timetables and runs depressing websites. It is also used in German as a jokey reference to buttocks themselves. Heine implies both meanings: the first meaning is applied to Platen's formal complexity; the second to Platen's obsession with young men.

Heine's talent for satire and sarcasm – quite appropriate to the times in which he lived – sometimes makes him a problematic author for the fastidious and elevated German literary mind. In the present case, after dancing around Platen with his rapier, Heine now goes in for the kill with club and sabre.

Since the Count masks himself sometimes in pious feelings, he avoids the precise specification of gender; only those in the know shall see it clearly; he believes he has hidden himself sufficiently from the great mass if he leaves out the word 'friend' from time to time, and on these occasions he is like the ostrich, who believes itself to be sufficiently hidden when it sticks its head in the sand so that only the rump remains visible. In fact, he is more a man of rump than a man of head, the word 'man' doesn't really apply to him at all, his love has a passive Pythagorean character, he is a pathikos, he is a woman, and in fact a woman that delights in other womanliness, he is at one and the same time a male lesbian.

Denn der Graf vermummt sich manchmal in fromme Gefühle, er vermeidet die genaueren Geschlechtsbezeichnungen; nur die Eingeweihten sollen klar sehen; gegen den großen Haufen glaubt er sich genugsam versteckt zu haben, wenn er das Wort Freund manchmal ausläßt, und es geht ihm dann wie dem Vogel Strauß, der sich hinlänglich verborgen glaubt, wenn er den Kopf in den Sand gesteckt, so daß nur der Steiß sichtbar bleibt. Unser erlauchter Vogel hätte besser gethan, wenn er den Steiß in den Sand versteckt und uns den Kopf gezeigt hätte. In der That, er ist mehr ein Mann von Steiß als ein Mann von Kopf, der Name Mann überhaupt paßt nicht für ihn, seine Liebe hat einen passiv pythagoräischen Charakter, er ist in seinen Gedichten ein Pathikos, er ist ein Weib, und zwar ein Weib, das sich an gleich Weibischem ergötzt, er ist gleichsam eine männliche Tribade.

[Heine 141]

Heine's remark about avoiding the specification of gender requires elucidation for those who do not speak German. In German the nouns applying to people (and their occupations etc.) take the gender of the real person. If the friend is a women the word is Freundin, if a man, Freund. Heine's point is that Platen is using circumlocutions to avoid referring to the objects of his passion as men.

After invoking an image of Platen as the ostrich with his head in the sand and his bottom exposed to the world, Heine tells his readers in no uncertain terms that Platen is a man whose actions are guided by his bottom, not his head.

Platen is no man – not even his sodomy is male. He is the pathikos, the Greek term for the submissive, penetrated male in an anal coupling. It was considered humiliating by the Greeks for an adult male to be on the receiving end of this loving penetration. Young men, boys and slaves were another matter. The Romans, in contrast, were more or less up for anything in this respect.

The modern word for the submissive male in a dominant relationship is 'bitch'. Although, as might be expected, the modern view of Greek homosexual practices is subtle and differentiated, the generally accepted view at Heine's time would have been closer to this:

It was certainly shameful when a man with a beard remained the passive partner (pathikos) and it was even worse when a man allowed himself to be penetrated by another grown-up man. The Greeks even had a pejorative expression for these people, who were called kinaidoi. They were the targets of ridicule by the other citizens, especially comedy writers. For example, Aristophanes (c.445-c.380) shows them dressed like women, with a bra, a wig and a gown, and calls them euryprôktoi, 'wide arses'.

'Greek Homosexuality' at livius.org [there is much more here for inquiring minds].

Heine then quotes a piece of Platen's poetry containing a line in which 'angels blissfully cuddle up tight [sich anschmiegen] to angels' (Wo selig Engel sich an Engel schmiegen). In a magnificent piece of satire, Heine ties the strands together using the Biblical story of Lot in the city of Sodom:

… we think straightaway of the angels who came to Lot, the son of Haram, and only escaped the tenderest cuddling up [Anschmiegen] after great danger and effort, which we read in the Pentateuch, where unfortunately the ghasels and sonnets are not communicated that were composed outside Lot's door.

… so denken wir doch gleich an die Engel, die zu Loth, dem Sohne Harans, kamen und nur mit Noth und Mühe den zärtlichsten Anschmiegungen entgingen, wie wir lesen im Pentateuch, wo leider die Gaselen und Sonette nicht mitgetheilt sind, die damals vor Loths Thüre gedichtet wurden.

[Heine 141]

In Genesis, Chapter 19, two angels visit Lot at evening, are offered hospitality and enter his house. Their arrival does not go unnoticed by the Sodomites and the two angels are threatened with anal rape:

4 But before they lay down, the men of the city, even the men of Sodom, compassed the house round, both old and young, all the people from every quarter:

5 And they called unto Lot, and said unto him, Where are the men which came in to thee this night? bring them out unto us, that we may know them.

6 And Lot went out at the door unto them, and shut the door after him,

7 And said, I pray you, brethren, do not so wickedly.

8 Behold now, I have two daughters which have not known man; let me, I pray you, bring them out unto you, and do ye to them as is good in your eyes: only unto these men do nothing; for therefore came they under the shadow of my roof.

9 And they said, Stand back. And they said again, This one fellow came in to sojourn, and he will needs be a judge: now will we deal worse with thee, than with them. And they pressed sore upon the man, even Lot, and came near to break the door.

10 But the men put forth their hand, and pulled Lot into the house to them, and shut to the door.

11 And they smote the men that were at the door of the house with blindness, both small and great: so that they wearied themselves to find the door.

Bible, Genesis 19:4-11, King James version.

The pure in heart may need to be prompted that in the phrase 'that we may know them', 'know' means 'know' in the Biblical sense – what Heine terms 'the tenderest cuddling up' – noting that, in the Biblical account, we are told nothing of the poetry, the 'ghasels and sonnets', that the raging mob of Sodomites at Lot's door wrote.

Lot's daughters, the poor girls, had much to put up with. Here they were offered to the mob as a substitute for angel bottoms. Later they would have to mate with their father in the interests of the continuation of the tribe:

Joachim Wtewael (1566–1638), Lot and his Daughters, c. 1600, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

After the flight from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, during which Lot's wife was turned into a pillar of salt, his two daughters got him drunk and seduced him so that they would bear his children (Genesis 11-4, 19). Another puzzlingly popular theme for painters down the ages. [This image was also used in connection with Heinrich Heine in a previous piece on Figures of Speech.]

Conclusion

More than one reader will be wondering at the point of the rambling disquisition on a long-forgotten literary feud in a foreign language. There are, in fact, several lessons to be drawn from this event.

In the absence of the word Homosexualität Heine reaches to the German word Hingebung to characterise Platen's sodomitic pederasty: 'devotion [to]'. For Heine, Platen's preferences are lifestyle choices, not an innate and ineradicable part of his personality.

Nowadays we have a culture of helplessness that bypasses individual responsibility. Homosexuals, alcoholics, drug addicts, bulimics, anorexics, the obese etc. etc. are the way they are because of some innate personality trait. Please note: I make no comment on whether or not these viewpoints are 'correct' or whether 'homosexual' should really be in a list along with 'alcoholics' and 'drug addicts'. That objection is 21st-century thinking at work. The Biedermeier mind, which is what we are studying, would have found this culture of helplessness incomprehensible.

Centuries of religious education had taught that man was a creature with free will and responsible for all his actions. The Fall of Man that 'brought Death into the World, and all our woe' had also equipped man with the freedom of will to choose the path of rightousness. Platen was not a man with a homosexual personality, but someone with sinful tendencies without the will or simply preferring not to control them.

However, Heine does characterise Platen's nature as feminine submissive, a 'male lesbian'. He does this using one of the few polite words available to him at the time, the literary word Tribade. Sappho on her isle of Lesbos had provided the name of her island to designate lesbian love. There was, however, no Classical equivalent for men. Heine's disgust at Platen is a quite Classical, not a Christian viewpoint, his contempt is for Platen the 'bitch', not Platen the sodomite. As far as I know, Heine never complained about Lord Byron's sodomitic activities, because the heroic, manly Byron was no one's bitch.

Without taking sides in the battle, we simply note that the opinions of the learnèd down the years about the Poets' War make an interesting sociological study in themselves. Those sensitised to homophobia are repelled by Heine's public flaying and outing of Platen; those sensitised to antisemitism are equally repelled by Platen's offensive jibes. Those sensitised to both take the 'both sides suffered' option.

But we hard-hearted ones must be clear: the battle may have damaged both parties, but it was Platen who suffered the most. Heine went on to build a reputation as one of the great German authors, second only to Goethe; Platen spent the rest of his brief life in Italian exile scouting for boys – his works are as good as forgotten. He would have been unable to find any tolerance or understanding in his own country, after Heine had outed him.

A life that included sodomitic activity was an extremely dangerous one. There were also plenty of other violations of the Christian rulebook that – if detected – could get a young person into trouble. In June 1814, Franz Schober, then 18 years old, was alleged to have been involved in a masturbation scandal (Selbstbefleckung) at the Kremsmünster academy. Schober was pining for Marie von Spaun at the time, so we can only presume that she was the object of his tribute.

Apart from Kupelwieser, Schwind and the independently wealthy Schober, all the members of the Schubert circles were dependent on positions in the bureaucracy of the Austrian Empire of Paperwork. Their careers would have evaporated on the slightest hint of deviant behaviour.

There were spies and narks everywhere, 'bluebottles' they were called, who hung around taverns waiting for incautious speech or behaviour, or were servants who earned some money on the side for reporting on their employers. The police in the Empire of Paperwork spent their days adding to and maintaining dossiers of information on all those unfortunates who crossed their path. Whatever was reported may not have led to immediate action – perhaps a more intensive surveillance for a while – but it would be on your record if ever needed. Favourite surveillance locations were the public spas such as those in Baden near Vienna; fortunately such leisured treatments were beyond the means of the Schubert friends, except, of course, for the Schober family.

It is often assumed that the secret police in Austria were only interested in rooting out political dissent. This is not the case: the criminal code stretching down from all the Habsburg emperors was extremely religiously based – despite the assumed reforms of the supposedly enlightened Joseph II. Put crudely, an enemy of the Catholic religion was an enemy of the state, since the two entities were so closed intertwined. Anticlericalism was viewed as merely a precursor of Jacobinism.

The censorship system, too, was very busy expunging all immoralities from literature, plays, operas and even images, it was not merely a guardian of political thought. Bauernfeld's kamikaze attempt to produce an opera based on a bigamy was doomed from the start.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!