Heloise Höchner's first and last love

Richard Law, UTC 2019-03-20 12:04 Updated on UTC 2025-02-01

The eternal female: Austrian edition

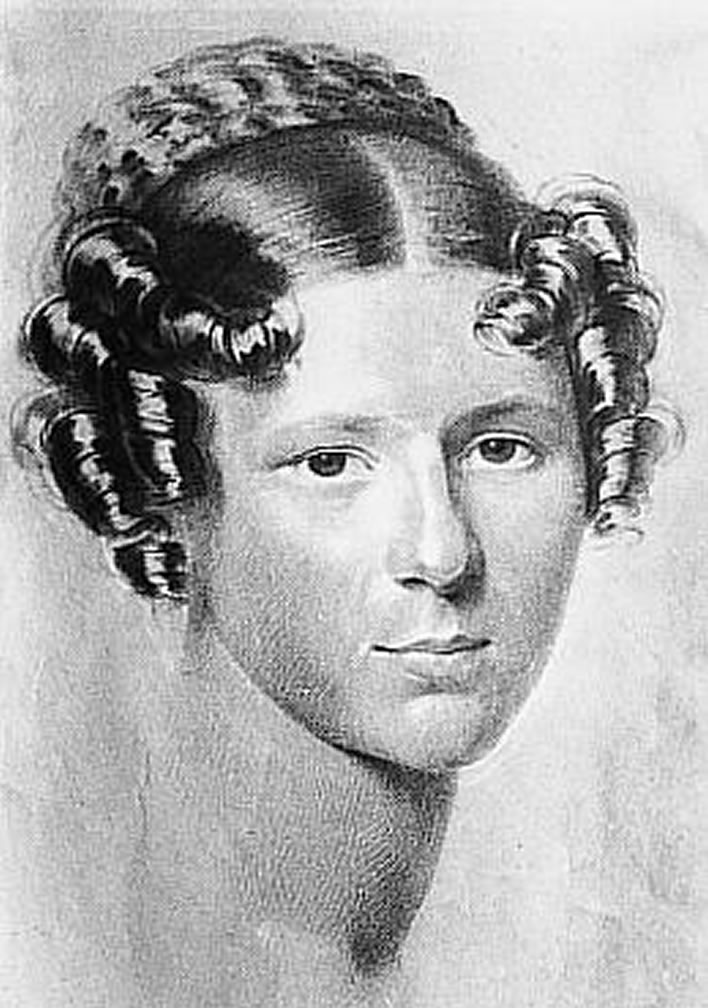

Sometime around 1830 the Austrian dramatist and poet Franz Grillparzer (1791-1872) encountered a young woman in Vienna. Continuing with our forced approximations – since no one else knows exactly – he would have been around thirty-nine at the time, she around twenty.

Hardly anyone outside Austria now knows or wants to know anything at all about Grillparzer, but towards the end of his long life he would be celebrated as Austria's National Poet.

Franz Grillparzer by Johann Josef Schmeller, 1826. Image: Goethe-Nationalmuseum, Weimar.

That encounter with the young woman made an impression on Franz that he recorded in his 1831 poem Begegnung, 'Encounter':

Begegnung

Wie schön sie war! Die bräunlich blonden Flechten

Bedeckt vom Strohhut mit dem breiten Rand,

Ging sie allein. – Doch nein! zu ihrer Rechten

Ging Unschuld, wie ein Kind sie leitend an der Hand.

Encounter

How beautiful she was! The reddish-blonde plaits under the straw hat with the broad brim – she walked alone. But no! At her right went innocence, guiding her like a child by the hand.

Das Antlitz Rosen; aber nicht wie rote,

Wie weißer Rosen Schmelz im Morgentau.

Das Auge, feurig kaum – denn Feuer drohte –

Nicht blau, nicht braun, fast fürcht ich, eher grau:

Her face roses; not red ones, but white roses dissolving in morning dew. The eyes, not fiery – since fire is threatening – not blue, not brown, almost, I fear, more like grey:

Und doch, hob sich der Wimper weiche Seide,

Und richtete der Stern sich heimatwärts,

In warmen Strahlen lächelnd wie die Freude,

In feuchtem Taue schwimmend wie der Schmerz.

And indeed, the soft silk of the veil was raised, and the star directed her homewards, smiling in warm rays like joy itself, swimming in moist dew like pain itself.

Nichts scharfgezogen in dem schönen Runde,

Die Nase wie kein Kunstblatt sie begehrt,

In weichem Einbug schließend zu dem Munde,

Halb kindisch fast nach aufwärts noch gekehrt.

Nothing hard-edged in the beautiful circle, the nose unlike those the illustrators draw, ending in a soft curve to the mouth, half childlike, almost turned outwards again.

Der Mund, in üppger Fülle leicht geschlossen,

Hielt nur zu sehr mit seinen Perlen Haus,

Doch Blumen gleich, von Zephirhauch umflossen,

Sog er die Luft und hauchte Balsam aus.

The fulsome mouth, lightly closed, kept its pearls too much concealed, like flowers breathed in the air from zephyrs and breathed out balsam.

Der Glieder Spiel – doch vor dem milden Scheine

Trat ich zurück, ob gleich von Wünschen heiß.

Der leichte Kahn, wie schön trägt er die eine,

Spräng noch ein zweites zu – Wer weiß? wer weiß?

The movements of the limbs – but I drew back from the gentle apparition, though filled with wishes. The small boat, how beautifully it carried the one person, were a second person to jump in — who knows? who knows?

Now under normal circumstances our critical scalpel would be lining up for the first of many incisions that would dissect this simpering tosh with all the heartlessness it deserves. In fact, we probably wouldn't even have wasted valuable pixels on it at all, were it not for the fact that it illustrates three things in great clarity:

Firstly, this maudlin rubbish is evidence for the poetic depths to which Austria's National Poet could sink. There is a reason his poetry is now largely forgotten, except by a few over-enthusiastic patriots.

Secondly, it shows us how smitten Grillparzer was with this girl – pointlessly smitten, though, because, as the poem tells us, he was psychologically incapable of doing anything about his smittenness other than musing to himself ineffectually about the possibilities that he could never bring himself to realise. 'Who knows?' indeed – not only once, but twice.

The goddess is rocking gently in front of him in the dinghy – assuming that this is a real boat and not a boaty metaphor. A fin-de-siècle French poet would have ripped his clothes off, dived in and made waves on the spot. Franz Grillparzer, on the other hand, has a little think about it all.

The third and most interesting thing about this poem is that the young girl in question was Heloise Höchner, whose boat – continuing the final metaphor of the poem – he really could have shared. He floated hers and she his. But ultimately Grillparzer was a milksop Abelard when he finally got to know his very own Heloise.

Franz Grillparzer by Moritz Michael Daffinger, 1827.

A few years after this first glimpse of Heloise, in the summer of 1834, Grillparzer was stagnating in one of his depressive lows. His attempt to obtain a post as the Director of the university library had been rejected and his recent plays had received only a lukewarm reception from the public and the critics. He had a gloomy and introspective personality anyway, but from time to time circumstances aligned that pushed him even deeper. The first part of 1834 was one of these times.

At the beginning of that year he had been dallying with a young woman called Anna von Kurzrock, the wife of a Kreiskommissar, a District Administrator. Anna Kurzrock will be a slightly familiar name to the Schubert enthusiasts on this website as the patron of a cultural salon in Vienna which is closely associated with the later Schubert circles. Moritz von Schwind is supposed to have done a portrait of her (which I have not been able to find).

It would be more accurate to say that Anna, under the cover name of 'Jessika', was dallying with the ineffectual Grillparzer, who was horrified by her indiscretion – he was, after all, in one of the on-again phases of his on-again-off-again relationship with the musician Kathi Fröhlich, one of the four renowned Fröhlich sisters. They were engaged in 1821 and spent the next fifty years painfully not getting married. The final on-again came in 1849, when Grillparzer, now almost deaf and suffering from eye problems, moved in with the sisters and let them look after him for another twenty-two years.

Katharina Fröhlich, ND. Chalk.Image: Bildarchiv der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Wien

At the beginning of 1834 there was a minor crisis: not only was Jessika sending letters to Grillparzer without any caution, she was even threatening to visit him. Grillparzer was left to square the circle with all those involved. Fortunately, she moved to Graz and the relationship went on in the background for some time – the artist needs admirers. An off-again period in the relationship with the long-suffering Kathi began once more.

In an attempt to raise Grillparzer's spirits, the painter, engraver and lithographer Philipp von Stubenrauch (1784–1848), who was at that time the costume and scenery director of the Hofburgtheater, Stubenrauch's wife and Grillparzer's aunt Johanna Theser (née Sonnleithner) took him away from the stuffy Viennese summer for an eight-week sojourn in Heiligenstadt, on the rural northern outskirts of Vienna. As it happened, Heloise Höchner, that beautiful boat girl from four years previously, was also there. She was twenty-four, Grillparzer forty-three.

She venerated him, the famous dramatist and poet, in the way only women can venerate such ne'er-do-wells. The middle-aged Grillparzer also acted according to stereotype, was fascinated by the effervescent Heloise, who with mother-tongue French could read his French favourites – Racine and Molière – to him, sometimes declaimed from memory. They were both flattered by each other's attentions. In Heiligenstadt, Grillparzer was at a safe distance from both 'Jessika' and Kathi. There were meetings and walks.

Standing on the heights

On one of the walks the pair ended up at the summit of the Kahlenberg at the northern end of Heiligenstadt, famous for its view over the city and down to the usually not at all blue Danube at its foot.

At that magical summer moment, as the sun went down, Heloise quoted by heart a passage from the third Act of Grillparzer's 1823 play König Ottokars Glück und Ende. The passage, a walk-on-walk-off speech by one of Rudolf von Habsburg's knights, Ottokar von Hornek, is a hymn of praise to the Austrian fatherland and even today warms the patriot's heart. It always works: if you want to warm a scribbler's heart, quote his own words back at him.

Wo habt ihr dessengleichen schon gesehn?

Schaut rings umher, wohin der Blick sich wendet,

Lachts wie dem Bräutigam die Braut entgegen!

Mit hellem Wiesengrün und Saatengold,

Von Lein und Safran gelb und blau gestickt,

Von Blumen süß durchwürzt und edlem Kraut,

Schweift es in breitgestreckten Tälern hin –

Ein voller Blumenstrauß, soweit es reicht,

Vom Silberband der Donau rings umwunden! –

Hebt sichs empor zu Hügeln voller Wein,

Wo auf und auf die goldne Traube hängt

Und schwellend reift in Gottes Sonnenglanze;

Der dunkle Wald voll Jagdlust krönt das Ganze.

Und Gottes lauer Hauch schwebt drüber hin,

Und wärmt und reift, und macht die Pulse schlagen,

Wie nie ein Puls auf kalten Steppen schlägt.

Where have you seen its like? Look around, wherever the gaze turns, laugh as the groom does to the bride! With bright meadow green and harvest gold, tapestried with linen and saffron, yellow and blue, sweetly fragranced with flowers and noble plants, it sweeps away in broad fields before us – a full bouquet of flowers, as far as it stretches, encircled by the silver ribbon of the Danube! – Raises itself to hills full of wine, where the golden grapes hang and swell to ripeness in God's summer light; the dark forests full of hunting joys crowns the whole. And God's gentle breath rests over it, and warms and ripens, and makes the pulse beat faster, as no pulse from the cold Steppes can beat.

In those weeks in Heiligenstadt her effect on the gloomy and depressive Grillparzer was profound: he cheered up and even the companions in his party noticed the positive effect that Heloise was having on him. The pair became soulmates – or at least Heloise thought so. Foolish girl.

Grillparzer's pulse was beating, but unlike those of Hornek and the great King Rudolf, he was psychologically incapable of doing anything about it. And, of course, the two other sputtering romances, Kathi and Anna, still had to be handled somehow.

The Höchners

Let's leave for a moment our lovestruck pair on the Kahlenberg watching the sun set upon imperial Vienna and ask: Who was this goddess who single-handedly cheered up Austria's National Poet? Here is the paragraph in which the Austrian literary eminence, Eduard Castle (1875-1959), described Heloise's background.

Her father Höchner, born in Zurich, now a bookkeeper in a Viennese wholesale company, was in his youth in service in the famous Burgundian wine town Nuits and there married a French woman, who gave him four children, two sons and two daughters. When Heloise was five years old her mother died and the widower sent the boys to relatives in Switzerland, the girls into a boarding school in Dijon. Four years later the family was reunited in Vienna, but only for a short time. The sons were sent to the Protestant High School in Pressburg [now Bratislava]. One of them, Konrad, later served in the Austrian army, as many another Swiss did. The two daughters, Heloise and Leonore, looked after the house for their father.

Ihr Vater Höchner, ein gebürtiger Zürcher, jetzt Buchhalter in einem Wiener Großhandlungshaus, war in seiner Jugend in dem berühmten burgundischen Weinort Nuits in Kondition gestanden und hatte sich dort mit einer Französin verheiratet, die ihm vier Kinder schenkte, zwei Söhne und zwei Töchter. Als Heloise fünf Jahre alt war, starb die Mutter, der Witwer schickte die Knaben zu Verwandten in die Schweiz, die Mädchen in ein Pensionat nach Dijon. Vier Jahre später vereinigte sich die Familie wieder in Wien, aber nur auf kurze Zeit. Die Söhne kamen an das evangelische Gymnasium nach Preßburg, einer von ihnen, Konrad, trat später, wie mancher andere Schweizer, in österreichische Militärdienste. Die beiden Töchter, Heloise und Leonore, führten dem Vater die Wirtschaft.

[Eduard Castle, Dichter und Dichtung aus Österreich, Amandus Verlag, 1951, p. 91.]

Castle's description of Heloise's origins is tantalising, but short on details and documentary evidence. We particularly miss her date of birth, which would allow us to come to the not unimportant fact of her age when the 43 year-old Grillparzer was dawdling with her. Her father's first name would be a matter of interest to us, too.

Relying on Castle, we have no more idea of her mother than that she is a Frenchwoman Höchner married in Nuits (which we have to assume is Nuits Saint Georges and not the other Nuits in the Yonne department, more than 100 kilometres away) and that she died when Heloise was five. We have no name, maiden name and no age.

That deeply dubious Viennese scribbler, Friedrich Schreyvogl (1899-1976), asserted in his rambling and nonsensical part-work about Grillparzer, Der ewige Bräutigam, 'The Eternal Bridegroom', which appeared in the Nazi Die kleine Wiener Kriegszeitung, 'The Little Viennese War Newspaper' in 1944, that Höchner's wife was a lady from Strasbourg. He also fantasises that Grillparzer and Heloise met at the small boating lake in the Prater, which he may have picked up from Begegnung. His account of the Grillparzer-Höchner relationship is so perverse and untrue, however, that we can ignore it without a second thought.

Since we don't have Heloise's birthdate, most of Castle's information is just vague decoration. We are given no date for the return to Vienna and no address for them there, so we have no hook we can use to follow the Höchners through the Viennese records.

I have no idea from which source Castle obtained this information, although he does mention later in his account that he had some conversations with the Romanian grandchildren of Heloise and her husband Costinesco. That said, Castle even fails to mention her husband's forename.

You will be spared the tedious narrative of the even more tedious twists and turns of the search for Heloise's family. Let's go straight to what we now can document.

Heloise Höchner, the French connection

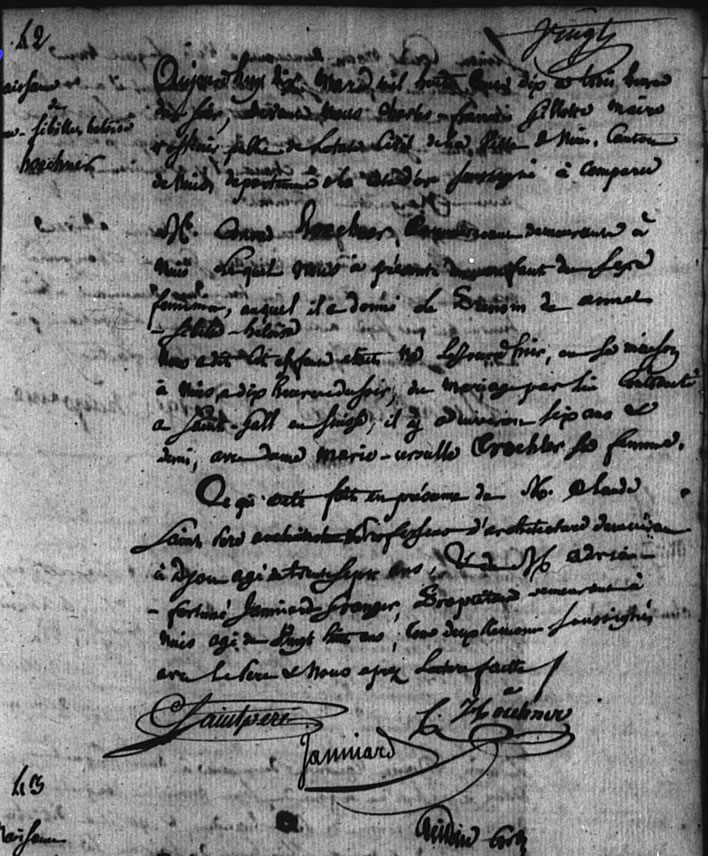

Heloise was born on 9 March 1810 in a house in Nuits Saint Georges, in the famous Côte d'Or region of Burgundy. Here is the registration of her birth, written out by the mayor of Nuits Saint Georges, Charles-François Gillotte, on 10 March:

Heloise Höchner's birth entry, Nuits Saint Georges, 10 March 1810 [born 9 March].

[N]aissance

de

anne-sibille heloise

hœchner

Aujourd'hui dix mars mil huit cent dix ans trois heures

du jour, devant Nous Charles-François Gillotte maire

et officier publique de L'etat Civil de la Ville de Nuits, Cantone

de Nuits département de la Côte d'or, soussigné a comparee

M. Conrad Hœchner, [?] demeurent à

Nuits Lequel nous à presenté un enfant du sexe

feminin auquel il a donné le prénom de annete

-sibille-heloise

Nous a dit qu'il être né le jour d'hier, en la maison

à Nuits à dix heures du soir, du mariage lui contracté

à Saint-Gall en Suisse, il y a [?] seize ans et

demi, avec dame marie ursula Trochler sa femme.

Ce qu'a eté fait en présence de M. Claude

Saint [?] ---- professeur d'architecture demeurent

à Dijon agé trente sept ans, et de M. Adrien-

-fortuné Janniard-Granger, propriataire demeurent à

Nuits agé de vingt huit ans; les deux temoines soussigné

avec le pere et nous après lecture faite.

Today tenth March one thousand eight hundred [at] three o'clock in the afternoon, before us Charles-François Gillotte mayor and public officer of the Civil Estate of the town of Nuits, canton of Nuits, department of the Côte d'or the undersigned

Mr Conrad Höchner [?] resident of Nuits, who has presented an infant of female sex to whom he has given the forename of Annete Sibille Heloise.

We have been informed that the child was born yesterday in the house at Nuits at ten o'clock in the evening, of the marriage of contracted at St Gallen in Switzerland seven and a half years ago with marie ursula Trochler, his wife.

This was done in the presence of M. Claude Saint [?] professor of architecture at Dijon aged thirty seven years, and M. adrien-fortuné Janniard-Granger, proprietor resident at nuits aged twenty-eight years old; the two witnesses have signed with the father and with us after reading:

Image: Tables et actes de l'état civil de Côte-d'Or, Registres paroissiaux et/ou d'état civil : 1809-1816, 10 March 1810. [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab.]

Despite its rambling formulaic style – which makes us long for the birth records written by the Josephinian civil servants of the Austrian Empire – the birth entry gives us a lot of information.

Heloise's father is Conrad Höchner (or Hoechner or one of its French phonetic approximations). We can now be sure that he was resident in Nuits Saint Georges at the time that Heloise was born (and not the other Nuits, in the Yonne). M. Gillotte's plume de sa tante was very definitely mal taillée, blunt, that Saturday afternoon, 10 March 1810, meaning that the title of Höchner's profession is unfortunately illegibly smeared (at least for my eyes).

A surprise comes when we read that Conrad Höchner and his wife were married not in France but in the parish of St Gallen, in the east of Switzerland. Höchner is a very common name thereabouts and is particularly localised around the town of Rheineck, right at the southern end of the Lake of Constance – or more precisely the southern beginning of the Lake of Constance, since the alpine Rhine enters the lake here and the water is flowing northwards. We can begin to doubt Castle's bold statement that he came from Zurich. Still, the Swiss are used to foreigners getting confused about precisely which village they hail from. And now there is yet another puzzle we have to grapple with: how did Conrad Höchner end up marrying a Frenchwoman in St Gallen?

A further surprise comes when we read that on that wedding day seven and a half years previously, Höchner's bride was called Marie Ursula Trochler (involving some phonetic guesswork). NB: For the avoidance of chaos, the French variant 'Ursule' has been stadardised throughout this article to the more general 'Ursula'. Ursula's correct maiden name is 'Trachsler'.

This is the earliest birth record for the Höchner family that I could find in the Nuits Saint Georges records. Castle supplies some seductive anecdotal detail about the two sons, but we have to conclude that they were not born in Nuits Saint Georges. According to this record, Conrad and Marie Ursula were married in St Gallen around 1802 and the marriage must have produced the two boys before the couple moved to Nuits Saint Georges.

Also interesting in this record is the high social status of the witnesses. The first of these is the architect and sculptor Charles Claude Saint-Père (1771-1854), here given as a 'professor of architecture'. Charles-Claude – here simply 'Claude' – was one of a long family line of architects and sculptors, all of whom are still remembered today for their baroque marvels and their restoration work. Just to keep us on our toes, his grandfather was Claude (sculptor fl. 1710), his father Charles (1739-?) and he was named Charles-Claude and was principally an architect. His greatest claim to fame is the near decade-long restoration of the tombs of the Dukes of Burgundy, started in 1818 when the French became nostalgic about all the nobs they had disposed of in that rush of blood to and from the head that started in 1789.

The second witness was Adrien-Fortuné Janniard, who was a well connected landowner in the town. He was scion of an old and long established family. His father, Joseph, served for more than twenty years as a Justice of the Peace in those turbulent times. He was killed in some sort of military exercise in 1816 and his son Adrien-Fortuné was immediately appointed in his place.

It is clear from these notable witnesses that by 1810 Conrad had secured a place for himself in the life of Nuits Saint Georges. These two men of such distinction were hardly likely to have been hanging around the Mairie on that Saturday afternoon ready to be roped in for a bit of witnessing. Even without the extra information about the witnesses that we have managed to gather, the two fine signatures give us a hint of their status and their education.

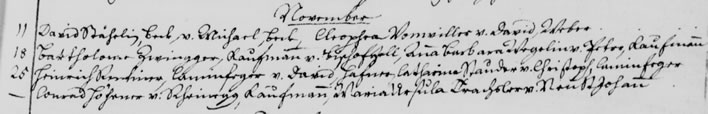

Heloise's sister Éléanore Höchner

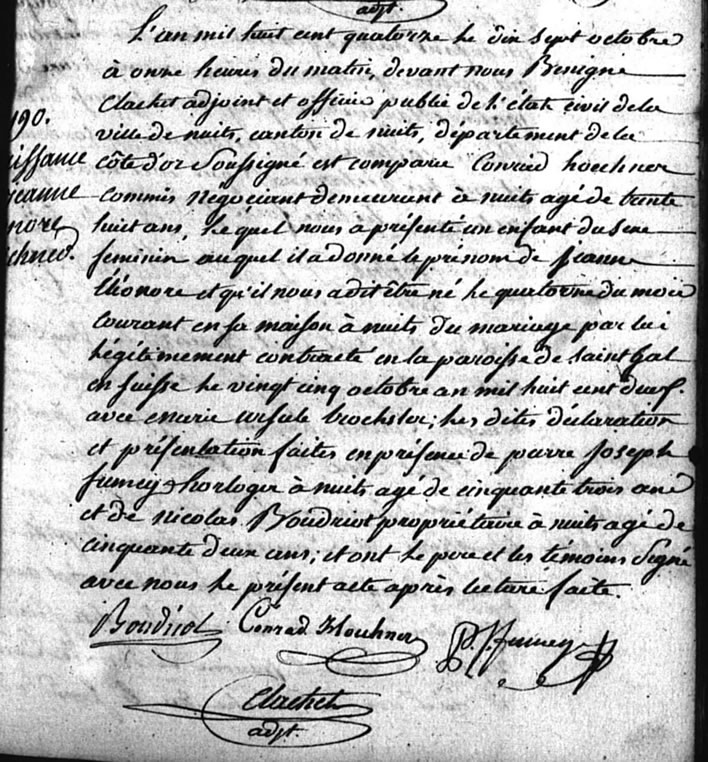

We meet Conrad Höchner once more in Nuits Saints Georges for the registration of the birth of the second daughter Jeanne Éléanore on 16 October 1814. From this birth record we can glean some additional information, particularly since the mayor Charles-François Gillotte, who had been scribbling with his aunt's blunt pen since 1803, had left office in 1813. The register of Jeanne Eleanore's birth was written with the sharp new pen of M. Bénigne Clachet, a deputy mayor.

Éléonore Höchner's birth entry, Nuits Saint Georges, 17 October 1814 [born 16 October].

[Na]issance

Jeanne-

[Éléo]nore

[Hoe]chner

L'an mil huit cent quatorze le dix sept octobre

à onze heures du matin, devant nous Bénigne

Clachet adjoint et officier public de l'état civil dela

ville de nuits, canton de nuits, département de la

côte d'or Soussigné est comparée Conrad hoechner

commis négociant demeurent à nuits agé de trente

huit ans. Lequel nous a présenté un enfant du sexe

feminin auquel il a donné le prénom de Jeanne

Éléonore et qu'il nous a dit être né le quatrieme du mois

courant en sa maison è nuits du mariage par lui

légitimement contracte en la paroisse de Saint Gal

de Suisse le vingt cinq octobre an mil huit cent deux

avec marie ursula trochler; les [dites] déclaration

et présentation faites en présence de paire Joseph

Fumey horloger à nuits agé de cinquante trois ans

et de nicolas Boudriot propriétaire à nuits agé de

cinquante deux ans; il ont le père et les témoins Signé

avec nous le présent acte après lecture faite.

[In] the year one thousand eight hundred and fourteen the seventeenth of October at eleven o'clock in the morning, before us Bénigne Clachet deputy and public officer Civil Estate of the town of Nuits, canton of Nuits, department of the Côte d'or the undersigned is compared

Conrad Hoechner assistant [wine] merchant resident in Nuits aged thirty eight years, who has presented an infant of female sex to whom he has given the forename of Jeanne Éléonore and who we told was born on the fourth of the present month in the house at Nuits of the legitimately contracted marriage in the parish of St Gallen in Switzerland on the twenty-fifth of October in one thousand eight hundred and two with marie ursula trochler; the declaration and presentation of facts were in the presence of Joseph Fumey, watch and clockmaker of Nuits aged fifty three years and of Nicolas Boudriot, property owner at Nuits aged fifty two years: the present document signed by the father and the witnesses and us after reading.

Image: Tables et actes de l'état civil de Côte-d'Or, Registres paroissiaux et/ou d'état civil : 1809-1816, 17 October 1814. [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab.]

On the basis of this record we now know that Heloise's sister was four and a half years younger than she was, a fact that makes Castle's assertions that they both went to a girls' boarding school after their mother's death somewhat problematic, since, if their mother died five years after Heloise was born, then Jeanne Éléonore was still a baby. We wonder whether the mother died as a result of Jeanne Éléonore's birth, but we have no information about this.

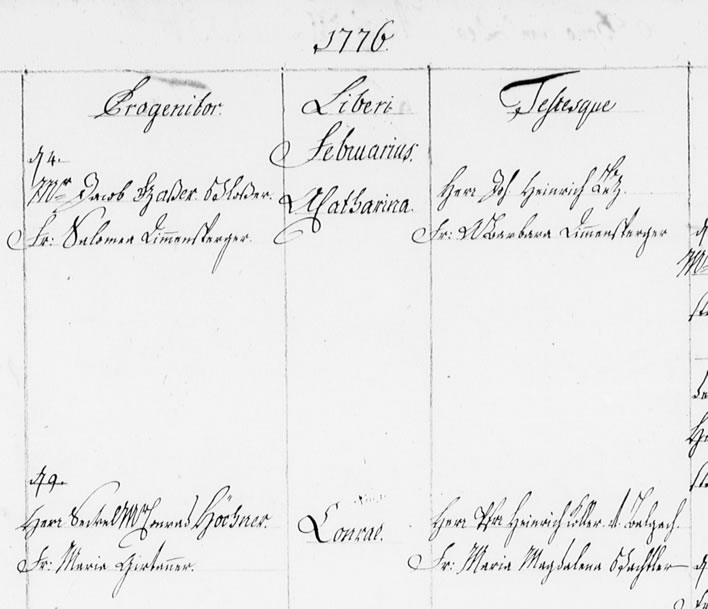

In a violation of the usual formula, Heloise's birth certificate had made no mention of the age of her father. In Éléonore's record, we learn that Conrad was thirty-eight years old, meaning that he would have been around thirty-four when Heloise was born, that he was around twenty-six when he married Marie Ursula and that he was born around 1776.

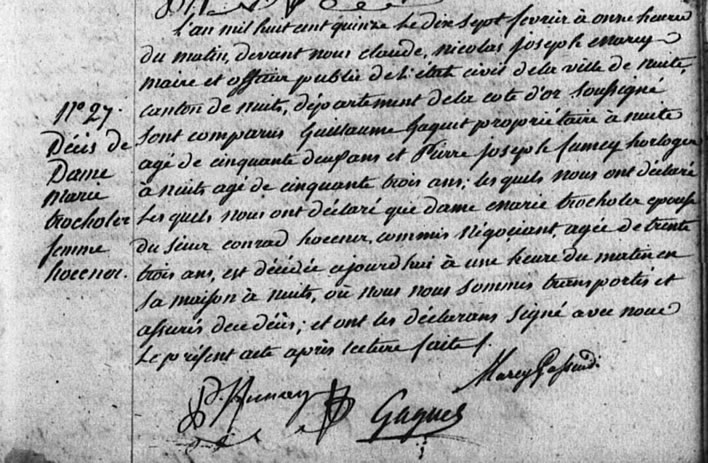

Castle's information about Marie Ursula's death is correct, she did die around five years after Heloise was born – and four months after Jeanne Éléonore, making Castle's tale about both sisters going to a girls' boarding school after their mother's death very problematic. From the death record we now know that she died on 17 February 1815 in Nuit Saint Georges:

L'an mil huit cent quinze le dix sept fevrier à onze heures

du matin … Lesquels nous ont déclaré que dame marie trocholer épouse

du sieur conrad hoecner, commis Négoçiant, agée de trente

trois ans, est décédée aujourd hui à une heure du matin en

sa maison à Nuits …

[In] the year one thousand eight hundred and fifteen [on] the seventeenth of February at eleven in the morning … Who have declared to us that dame Marie Trocholer, wife of M. Conrad Hoechner, assistant [wine] merchant, aged thirty-three years, died today at one o'clock this morning in her house in Nuits …

Image: Tables et actes de l'état civil de Côte-d'Or, Registres paroissiaux et/ou d'état civil : 1809-1816, 17 February 1815. [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab.]

In Jeanne Éléonore's birth record we had a legible job description for Conrad: 'commis négoçiant', assistant dealer – in this case most probably in the Burgundy wine trade. This job description is repeated in the death entry for Marie Ursula. The death entry also gives us her age, thirty-three, meaning she was born in 1781-2.

We also have a specific date for the marriage: 25 October 1802. In a further set of phonetic spellings, M. Clachet's writing gives another twist to our interpretation of Mrs Höchner's maiden name: Marie Ursula Trocholer.

In contrast to the elevated personages who were witnesses on Heloise's birth record, for her witnesses Éléonore has to make do with a clockmaker, the fifty-three year old Joseph Fumey and the fifty-two year old 'proprietaire' Nicolas Boudriot. Fumey belongs to a widespread tribe of French clockmakers with that surname, but as far as I can tell has no individual triumphs to his name that have not disappeared over the thundering cataract of history. He also appears as a witness on Marie Ursula's death record. Nicolas Boudriot has met a similar fate.

Whilst we are grateful for these crumbs from the archives, we have to temper our joy with the observation that most of these 'documentary facts' are not necessarily true. The French civil servant of the time is carefully precise about this: Both Gillotte and Clachet make the formulaic point of noting that the information that they record has been given to them by Höchner et al. – 'qu'il nous a dit'. No supporting evidence is involved. As far as we can see, Höchner was not required to produce his own birth and marriage records so everything we read is only a reflection of whatever he chose to tell the administrator.

Höchner's statements about his marriage and a specific date lead us to St Gallen. As already noted, there were many Höchners around St Gallen and particularly the vicinity of Rheineck at the time (and still today), so on that basis alone Conrad's statement to Clachet is plausible. Rheineck had a minor wine growing tradition and was at least until the middle of the 19th century an important transit place for goods. It is also on the Swiss-Austrian border, which lends a slight plausibility to Castle's tale of Höchner's son Konrad (a name we now know he shared with his father) serving in the Austrian army.

Unfortunately, the simple French deputy scribbler's convenient phrase 'in the parish of St Gallen' does not reflect the complexity of Swiss administration at the time. After much futile searching in parish registers, it was orderly Swiss civil administration – that sense of local roots that is still alive today – that produced the results we needed.

The Swiss connection

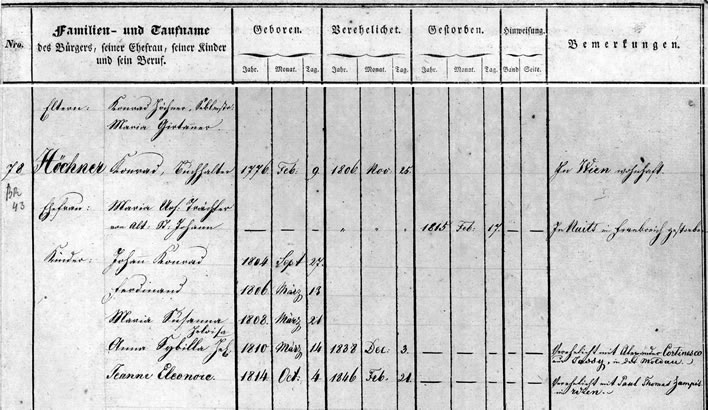

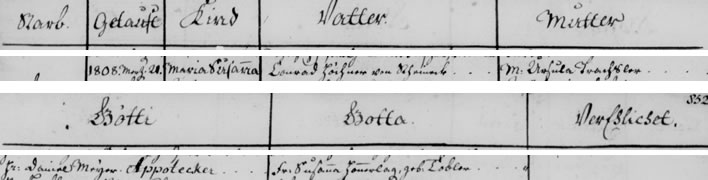

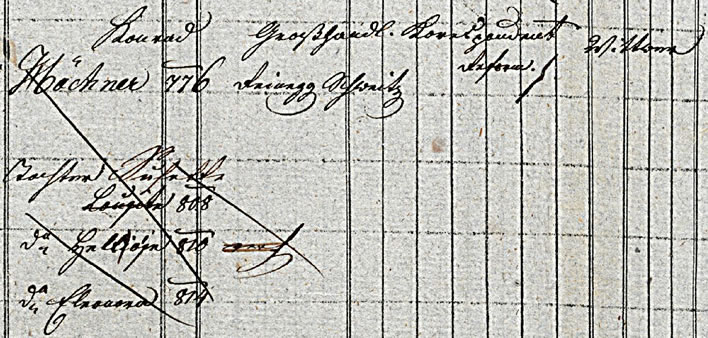

Fortunately, the guess that Conrad Höchner belonged to the tribe of Höchners from around the town of Rheineck proved to be correct. In the Bürgerregister, the 'Register of Citizens' for Rheineck we find an extremely complete entry for Conrad and his family. Here it is:

The entry for Conrad Höchner in the Bürgerregister, the 'Register of Citizens', for the town of Rheineck, Canton St Gallen, Switzerland. Image: All the images in this section are taken from the Staatsarchiv St. Gallen | ZVB 99/59.01 Rheineck: Bürgerregister Band A | 1785-1899. [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab.]

Here is a detail of the entry for Conrad Höchner and a transcription. The transcription also contains information from sources that will be discussed later in this article. Dates in {braces} are those of the French records; dates in bold are considered to be reliable or verified against an independent source:

|

Familien- und Taufname

Surname and baptismal name |

Geboren

Born |

Verehelicht

Married |

Gestorben

Died |

| Eltern: — Konrad Höchner, Seklmstr* — Maria Girtanner |

05.05.1726 01.06.1740 |

23.04.1775 ditto |

1780 1794 |

| Höchner Konrad, Buchhalter | 09.02.1776 |

25.11.1806

{25.10.1802} |

12.02.1847 |

| Ehefrauen: — Marie Ursula. Trächler — von Alt St. Johann |

7?.02.1782 {??.??.1781-2?} |

ditto {ditto} |

17.02.1815 |

| Kinder/Children: | |||

| — Johannes Konrad | 27.09.1804 | ? | 12.01.1835 |

| — Ferdinand | 13.03.1806 | ? | ? |

| — Maria Susanna | 21.03.1808 | ? | ? |

| — Anna Sybilla Joh[anna] Heloisa | 14.03.1810 {09.03.1810} |

03.12.1838 | ? |

| — Jeanne Eleonore | {04.10.1814} | 21.02.1846 | 22.06.1876 |

* Seklm[ei]st[e]r is a rendering of Säckelmeister, a term for someone who is responsible for receiving and accounting for funds, usually for some public body. It was in widespread use in the Middle Ages in German-speaking countries, but has now been replaced by Schatzmeister, 'Treasurer', particularly in Germany and Austria. In Switzerland it is still used in official designations of some positions. It literally means 'Master of the Purse'. From this entry we see that the son, at the time of his marriage a Buchhalter, a bookkeeper, was following in the father's financial footsteps.

It is frustrating that the date which interests us most, that of the birth of Heloise, is the date to which some uncertainty is attached. Unless my struggling eyes have misled me completely, M. Gillotte's blotchy birth record was written on 10 March 1810. At some point the date of her birth was recorded in the Register of Citizens of Rheineck as 14 March 1810. She married and died in Jassy, so all other possible confirmation is somewhere in Moldova and thus out of our reach for the moment. M. Gillotte's contemporary account has to take precedence over the secondhand date in the Register of Citizens.

The tribe of Höchners in Rheineck is a very extensive one, but since we are not interested in constructing their complete family tree we can pick out just the information we need to paint a picture of Heloise Höchner's background.

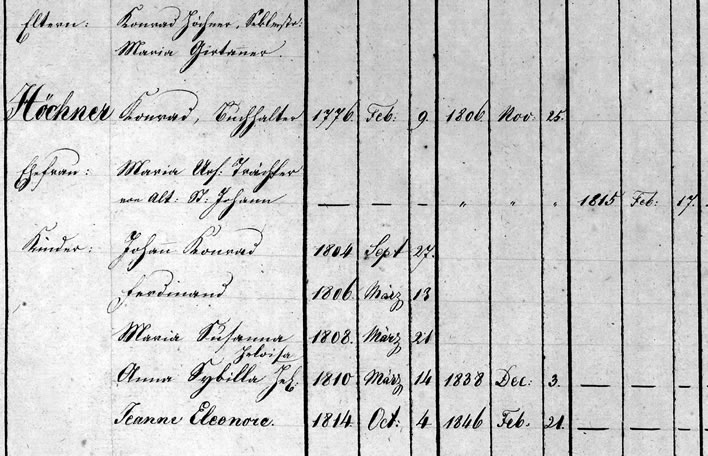

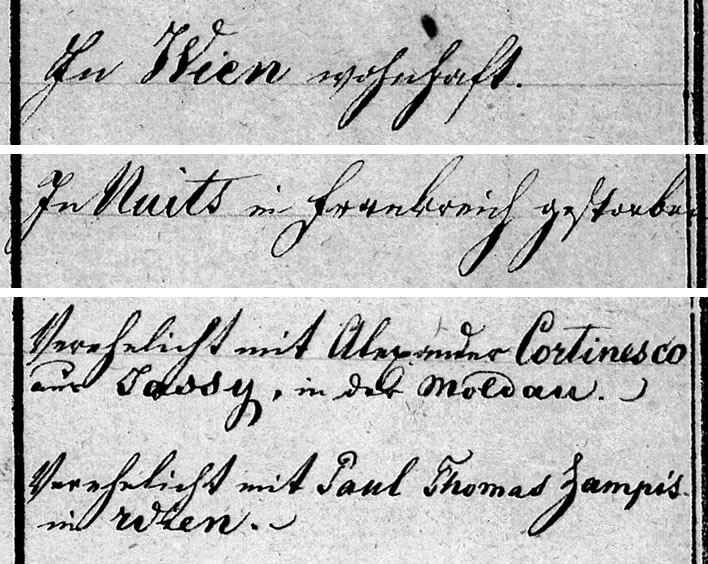

Let's just make sure that we have Conrad Höchner's correct birthdate. Here is the entry in the Tauf-, Ehe- und Totenbuch, 'Baptism, Marriage and Death Register' for Rheineck, 1772-1840:

1776 Februarius dies 9. Progenitor | Liberi | Testesque

Herr Johannes Konrad Höchner. | Konrad. | Herr [?] Heinrich Zoller

Frau Maria Girtanner. | | Frau Maria Magdalena [?]

Image: Staatsarchiv St. Gallen | ZVA 12.1412 - Rheineck (evangelisch-reformiert): Tauf-, Ehe- und Totenbuch | 1772-1840. [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab.]

Readers will be delighted to hear that this week is BOGOF week in the Figures of Speech Archival Research Department. We can bring you, at no extra charge, the information that Conrad's father and mother, Konrad Höchner and Maria Girtanner, were married on 23 April 1775, less than ten months before Conrad junior was born. He was thus their first child.

The marriage of Konrad Höchner (senior) and Maria Girtanner. According to this entry, Maria was born on 1 June 1740, was therefore 34 years old at her marriage.Image: Staatsarchiv St. Gallen | ZVA 12.1412 - Rheineck (evangelisch-reformiert): Tauf-, Ehe- und Totenbuch | 1772-1840.

The punctiliousness of the Swiss authorities in Höchner's home town in recording these events in distant places in the Register of Citizens for Rheineck is quite remarkable.

More worrying, though, is the fact that the date of the marriage in the French records differs by four years from the date of the marriage given in the Swiss records. Clachet recorded the marriage as being on 25 October 1802; the Swiss, on the other hand, have the date as 25 November 1806. If the Swiss are correct – and why wouldn't they be? – the Höchner's first two children were illegitimate. Unlike the case of the differing birth dates, we would prefer to take the Swiss date for the wedding – the Swiss authorities after all must know this date with more certainty than the French.

It is no surprise, therefore, that we find the confirmation of the date of the marriage as 25 November 1806 in the Ehebuch, 'Marriage Register' of the Protestant church in St Gallen:

[1806] November 25. Conrad Höchner von Rheinegg, Landsmann, et Maria Ursula Trachsler von Neu St Johann.

[1806] November 25. Conrad Höchner from Rheineck, citizen, and Maria Ursula Trachsler from Neu St Johann. NB: Ursula is sometimes given as coming from Alt St Johann or Neu St Johann, the two are about two kilometres apart, thus the difference should not worry us.

Image: Staatsarchiv St. Gallen | ZVA 12.735 - St.Gallen (evangelisch-reformiert): Ehebuch | 1769-1840. [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab.]

This entry not only confirms the date of the marriage as 25 November 1806, it also confirms our initial guess that Conrad and Ursula were Protestant. It also confirms that Conrad was telling the truth when he informed the two administrators in Nuit Saint Georges that his marriage was consecrated in the 'Parish of St Gallen'. The question of why the pair got married in St Gallen and not in Rheineck or Alt St Johann remains unanswered. Perhaps the two children born out of wedlock may have been a factor.

From Castle's account we expected there to be two sons, but the Swiss Register of Citizens for Rheineck tells us that Heloise had an older sister, Maria Susanna. Her baptism took place on 21 March 1808 and was recorded in the Taufbuch, the 'Baptism Register' of the Protestant church in St Gallen:

1808.März.21 | Maria Susanna | Conrad Höchner von Rheineck | M[aria]. Ursula Trachsler | Hr: Daniel Meyer. Appotecker | Fr. Susanna Honerley, geb. : Tobler.

1808.March.21 | Maria Susanna | Conrad Höchner from Rheineck | M[aria]. Ursula Trachsler | Mr Daniel Meyer. Pharmacist | Mrs Susanna Honerley, née Tobler. Image: Staatsarchiv St. Gallen | ZVA 12.766 - St.Gallen (evangelisch-reformiert): Taufbuch | 1740-1828. [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab.]

Although I have not yet found any baptism records for the two sons, at least we get some details of the Höchners' other children in the citizenship record. We also we get some extra information in the Bemerkungen, 'Remarks' column:

These tell us that Conrad Höchner, In Wien wohnhaft, was 'residing in Vienna'. In this context, it is interesting that his earlier departure for Nuit Saint Georges is not documented at all, suggesting that that absence was viewed as temporary, whereas the move to Vienna had the status of a more permanent departure from the Heimat. The separation was not complete however: he is still regarded as only wohnhaft, 'residing in' Vienna. Even today, Auslandschweizer, 'Swiss abroad', of whom there are around three-quarters of a million at the moment, remain connected to their Motherland by an invisible but important umbilical cord that is only cut when citizenship is officially renounced.

In Höchner's time the connection was to the place of birth, then the canton; the Motherland barely existed. We might speculate whether Napoleon's jackboot on the Switzerland of this time (see our remarks below) encouraged cooperation with the local authorities in France, but this is a question that only people who know what they are talking about can answer.

We are also told that Marie was In Nuits in Frankreich gestorben, 'died in Nuits in France'.

We even get the first name of Heloise's husband, Professor Costinesco, which Castle had neglected to tell us: Verehelicht mit Alexander Cortinesco aus Jassy, in der Moldau, 'was married to Alexander Cortinesco [recte Costinesco] from Jassy, in der Moldau' on 3 December 1838.

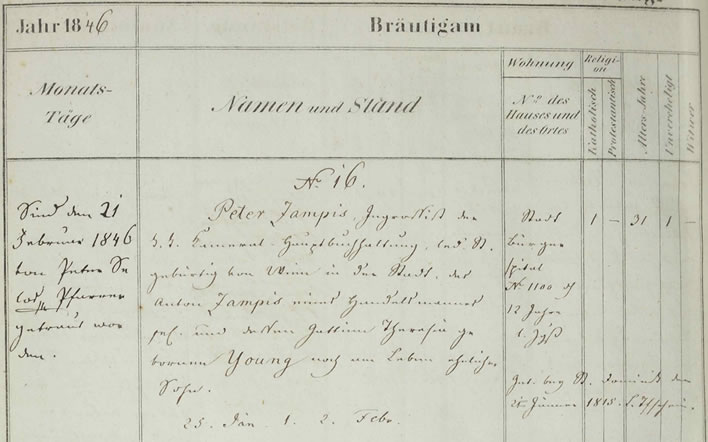

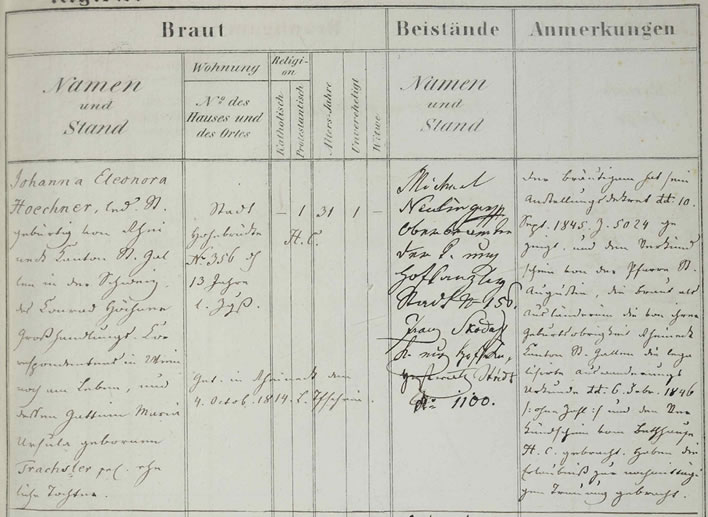

We are also told that Heloise's younger sister, Jeanne Eleonore Verehelicht mit Paul Thomas Zampis in Wien, 'was married to Paul Thomas Zampis in Vienna' on 21 February 1846. The date is correct but the bridegroom was a civil servant called Peter Zampis.

Custer's last band

A further source of information about the Hochners is contained in a genealogy of the leading families of Rheineck Genealogie der vor 1800 in Rheineck verbürgerten Geschlechter, compiled from church records by the pharmacist und Mayor of Rheineck, Heinrich August Custer (1869-1950). Strictly speaking, this remarkable and painstakingly executed work has to be regarded as a secondary source, but nevertheless serves as a useful confirmation of what we know so far. But there are one or two surprises.

One big surprise is that Conrad Höchner was the first son of his father's third marriage.

Conrad's father Hans (or Johannes) Conrad Höchner was born on 5 May 1726. Custer gives his origin as the village of Bernang, the modern Berneck. At the mention of Berneck the hearts of our Swiss readers will flutter, because this, of course, as everyone must know, is the home village of the tennis champion Roger Federer.

Hans Conrad married his first wife Martha Ritz (b. 1730) in 1750 and was to spend the next 37 years fathering children, 14 in all. The first nine of them were in the fifteen-year marriage with Martha. Most of them were short-lived but four survived into adulthood. After the ninth, in 1764, Martha herself died, which must have been a bit of a relief for her.

The connubial bed had scarcely cooled before Regina Pfeiffer (b. 1732) slipped between the sheets in 1766 and gave the overactive Hans Conrad another three children to bring his total up to twelve. All three died in infancy, however.

We are unsure when Regina died, but Hans married his third wife, Marie Girtanner (b. 1740) in 1775. As we have already noted, Conrad, who would become Heloise's father, was born shortly thereafter (Custer has his birthdate as 01.02.1776, but this is incorrect). A sister, Marie Elisabeth, was born about a year later in 1777 but died in infancy. After fathering fourteen children Hans Conrad lived on, obviously in a state of exhaustion, until he died in 1780 around 54 years old. Conrad junior was around four years old when his father died and around eighteen when his mother died in 1794. It would be another twelve years before Conrad married.

But the biggest surprise for those of us who followed Castle's account is that Conrad's wife, Marie Ursula Trachsler is definitely not a French woman. Castle's assertion that she was a French woman he married in Nuits is totally false, although the phonetic spellings of the French records – no French mayor could cope with 'Trachsler' – misled us for a time into following Castle's error. The pure Swissness of her name in the Swiss records, though, bring us back to our senses.

Marie Ursula was a genuine, dyed in the wool Swiss girl from the Toggenburg, a part of St Gallen in the foothills of the alps, now something of a ski resort. Custer tells us that her father was Notker Trachsler from St Johann. Notker (840?-912) ('the Stammerer') was the name of the 'Monk of St Gallen' who did so much to chronicle the life of Charlemagne. His roots are in the region of the Toggenburg, so it is quite reasonable for us to associate Notker Trachsler with the local saint and thus to associate his daughter Marie Ursula with Toggenburg – Swisser you cannot get.

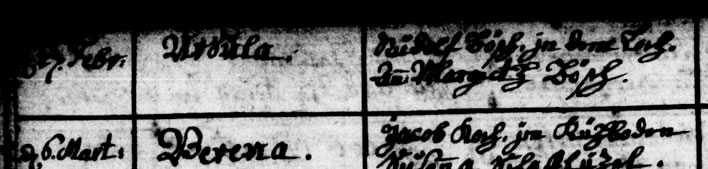

Custer does not supply the date of her birth, unfortunately, but some calculations on the basis of the French records ('agée de trente trois ans' on 17 February 1815) suggest 1781 or 1782 in Alt St Johann. Which is indeed where we find her in the parish records, baptised on (a smudge I take to be) 7 February 1782:

dies 7? Feb. | Ursula | Herr Notker Trachsler [?]. / Frau Margreta Zopf.

Image: Staatsarchiv St. Gallen | ZVA 12.007 - Alt St.Johann (evangelisch-reformiert): Tauf-, Ehe- und Totenbuch | 1692-1874. [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab.]

The last minor puzzle, which should not detain us long, is that Custer writes of Conrad Höchner that he was a Kaufmannsdiener in Paris, später in Wien, a 'commercial assistant in Paris, later in Vienna'. It doesn't really matter – it is just another mumble in the game of Chinese whispers that is archival research. All will become clear, we hope, when we track down Conrad and his girls in Vienna.

Leaving Switzerland

If we ever find out the story of the Höchners' journey to Nuits Saint Georges it will be a complex one, that much is sure. Europe was in turmoil at the time – France certainly, but Switzerland in particular.

We have already mentioned in the context of Albrecht von Haller's unfortunate time in the pit of corruption that was Berne, that Switzerland's reputation for rationality and peacefulness is a relatively late invention dating from the founding of the Swiss Confederation in the middle of the 19th century. By the end of the 18th century, the lawlessness and absolutism of the little tyrants who governed the fiefdoms of Switzerland had become intolerable.

Because of this, the principles behind the French Revolution seemed quite amenable to many Swiss of the time. After Napoleon's success in the War of the Second Coalition (1792-1797) Prussia and the old enemy Austria were on the back foot. The time had come when the downtrodden Swiss could realistically think of overthrowing their own petty tyrants in the French manner. A wave of revolution swept across Switzerland starting on the western border with France and rolling across the whole country to the east. Napoleon's troops and agents supported the movement both actively and clandestinely and by 1798 the Swiss Republic had been founded.

Conrad Höchner would have been around twenty-two at this time. Ultimately, what little resistance there was was futile. On 9 September 1798, ten thousand French troops hacked to death more than 400 men, women and children in the villages of Canton Nidwalden (around the town of Stans) and burnt many hundreds of houses and a number of churches to the ground. The French noted how bitterly fanatical the opposition to them had been, a bitterness that in turn drove them to such a bloodthirsty reaction.

The Swiss Republic lasted five years – five years during which the Swiss came to regret bitterly allowing themselves to become a satellite of France. Access to the riches of Switzerland came at just the right moment for Napoleon, who had armies to pay and battles to fight. The Swiss gained centralised government and numerous ancient wrongs were righted, but their country effectively ceased to exist and it was mercilessly plundered.

Everything that was characteristically Swiss – the number and naming of the cantons for example – was brutally remodelled according to French ideas. The Swiss had jumped out of the petty tyrants' pan into the great tyrant's fire. What would Wilhelm Tell think?

It is no mere coincidence that Schiller's play of that name, which established Tell's legendary status for posterity, was written in 1804. Schiller never visited Switzerland, relying on friend Goethe (who had been there) to supply the local colour, but his tale of the struggle of the tiny nation state for freedom from the mighty oppressor – then the Austrians, now Napoleon – came at the right time for both Switzerland and the nascent German nation.

The misery was at its height at just the time Conrad and Ursula were presumably beginning their relationship. Then, around 1803, Napoleon lost interest in Switzerland – it had served its purpose. He withdrew his troops, leaving the Swiss to get on with it.

Bits of the old, petty Switzerland – the 'patrician' Switzerland – returned straight afterwards in 1803, as did even more bits in 1815, when Napoleon was safely parked out of the way on St Helena and the European order had been re-established at the Congress of Vienna.

It appears that Conrad Höchner was in Rheineck for most of those years of turmoil and then moved to Nuits Saint Georges some time after the birth of his daughter Maria Susanna on 21 March 1808. We have no idea whether the couple's three existing children went with them to Nuits. All we know is that Heloise was born in Nuits almost exactly two years after the birth of Maria Susanna in Rheineck. Conrad and some portion of his family left Nuits sometime after the death of Marie Ursula in 1815.

Furthermore, the years 1816 and 1817 are famous in Europe as the 'hunger years' and Switzerland suffered as much as any country did. That Conrad did not return to the Motherland but got a job in Vienna therefore does not surprise us at all. Rheineck, his Heimatdorf, 'home village' was in a particular state of economic decline throughout the 19th century.

The outlet of the Rhine in the Lake of Constance was progressively silting up, strangling the boat transport that had given the village its living. Other forms of transport were emerging. Notable around the middle of the 19th century are the numbers of residents who packed up and left for America, where new opportunities beckoned.

The Höchners in Vienna

Let's try and find some basic information about Conrad Höchner and his family in Vienna.

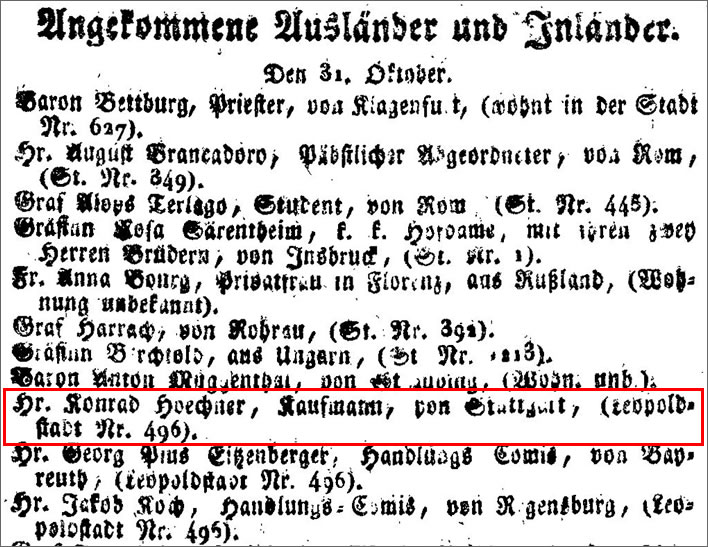

The Wiener Zeitung of 2 November 1816, under the rubric Angekommene Ausländer und Inländer tells us that Herr Konrad Hoechner, Kaufmann, 'businessman' arrived from Stuttgart in Vienna on 31 October and that he is living in Leopoldstadt, house no. 496.

'Foreigners and Natives arriving in Vienna', 31 October 1816. Image: Wiener-Zeitung, 307, Samstag den 2. November 1816. ANNO.

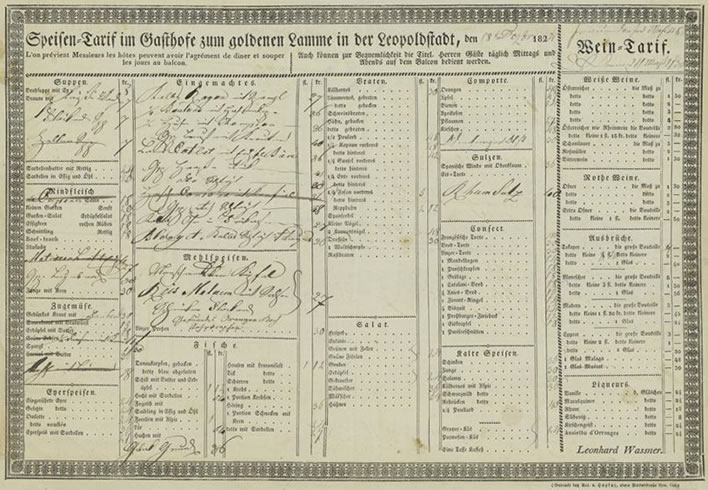

The sharp-eyed will notice that a number of those arriving on the same day gave their address in Vienna as the same house number, not a surprise since this was the well-known Hotel Goldenes Lamm, 'Golden Lamb Hotel', in the Praterstraße, well positioned on one of the key routes into and out of Vienna.

The menu in the Gasthof zum goldenen Lamme in der Leopoldstadt in 1824. Conrad Höchner would not have gone hungry. Image: Online zoomable.

Whether his children were with him, and if so, which, is currently unknown, but it seems unlikely, since at this moment his children are still quite young: Johann Konrad (12), Ferdinand (10), Susanne (8), Heloise (6) and Eleonore (2). What he was doing in Stuttgart before he arrived in Vienna is also currently a mystery. At least we know now that he didn't hang around in Nuit Saint Georges after Ursula's death on 17 February 1815.

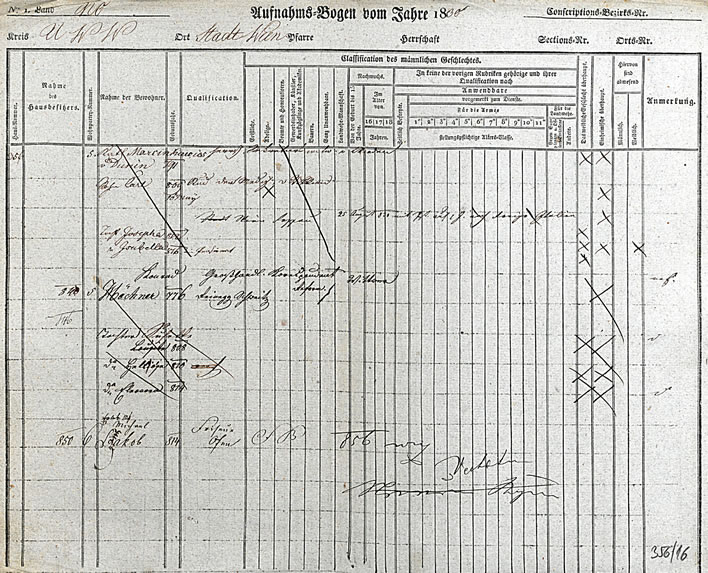

The next trace that we have of Conrad is the Conscription-Bogen, the 'conscription record' for house no. 356 in the Innere Stadt. The primary purpose of the document was to record the presence of men suitable for military service, as we saw when the Schubert family moved to the new school building in the Rossau.

Unfortunately, the date on the form only gives the year that the form was started, in this case 1830, when the previous tenant moved in. At some time after that Conrad, Susanne, Heloise and Eleonore are recorded as resident. We know that Heloise moved out in November of 1838, so it follows that this record was created sometime between 1830 and 1838. Eleonore was married on 21 February 1846, and on that occasion her residence is also given as house no. 356, now known as Höhenbrücke 356.

The Aufnahms-Bogen / Conscriptions-Bogen 'Conscription Record' for Haus Stadt Nr. 356. Image: Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv. [Click to show a larger image in a new browser tab.]

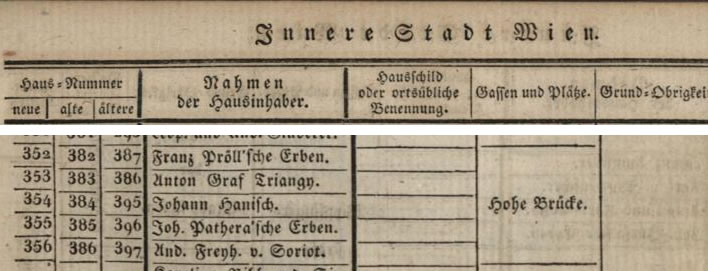

Here is house no. 356 in the 1829 edition of Anton Behsel's always useful street index, which links it to the street name Hohe Brücke:

House no. 356 in Behsel's 1829 listing. Image: Online zoomable.

The detail view below shows us that at the time of registration the residents were Höchner Konrad | [born 1]776 Reinegg Schweiz | Großhandel Korrespondent and his three daughters, Susanna [born 1]808, Heloise | [born 1]810 and Eleonore | [born 1]814.

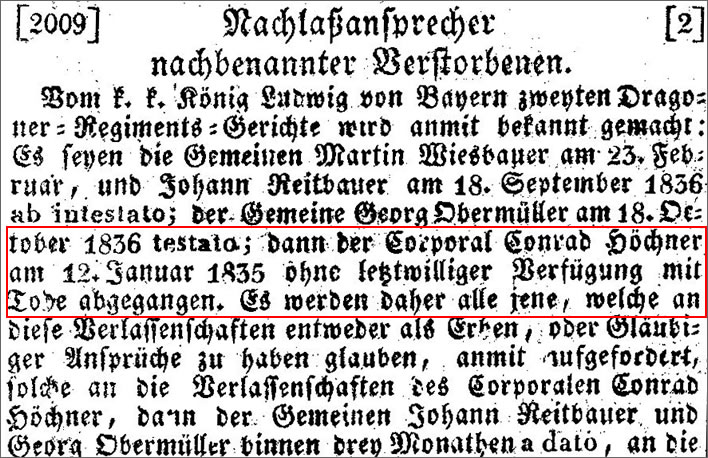

As Castle suggested, Conrad Höchner's older son, Johann Conrad, did indeed join the military. He died 30 years old on 12 January 1835 with the rank of corporal in the k. k. König Ludwig von Bayern 2. Dragoner-Regiment, as reported by the Stabsstation Padua, 'Staff Office, Padua'. He didn't leave a will, so was clearly not expecting whatever happened to him.

Corporal Conrad Höchner died intestate on 12 January 1835; the army is searching for anyone having a claim on his estate. Image: ANNO.

Why is Padua relevant, you ask? Because at that time Imperial troops were busy suppressing the uprising of the Italian nationalistic, anti-papal movement known as the Carbonari, that had broken out in Italy in 1831. The uprising had all but been supressed by the beginning of 1835, but if he did die in military action, Conrad junior was one of those unlucky ones who met their end just before the end, as it were.

Schubert fans may be scratching their heads wondering where they have hear of the Carbonari uprising. It won't take them long to recall that Second-Lieutenant Johann Senn, the great friend of Schubert's youth, was marching with the Tyrolean Kaiser-Jäger in the service of his emperor during those five years, too.

Heloise married in December 1838 (which we discovered from the marginal notes in the Rheineck Citizens' Register and which we shall discuss later).

Eleonore married Peter Zampis, an administrator in the imperial civil service, on 21 February 1846. That marriage was also mentioned in a marginal note in the Rheineck Citizens' Register, but we now see that the name of the bridegroom was completely garbled there:

Marriage of Johanna Eleonora Höchner on 21 February 1846 with Peter Zampis, Pfarre Schotten, Trauungsbuch 1843-1850, fol. 99. Image: online. [Click to show a larger image in a new browser tab.]

There is nothing startlingly new in Eleonore's marriage record, but it confirms, not that we need anymore confirmation, that she was born on 4 October 1814 and that her mother's name was Maria Ursula, née Trachsler. Eleanore died, 62 years old, on 22 June 1876; her husband Peter Zampis died, 81 years old, on 20 December 1895. With him we have almost reached the 20th century.

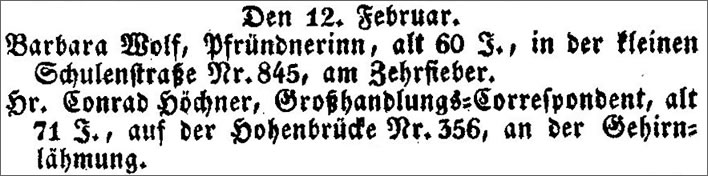

Conrad Höchner died, 71 years old, on 12 February 1847 in Höhenbrücke no. 356 of a stroke.

Announcement of the death of Conrad Höchner (12.02.1847) in the Wiener Zeitung for Tuesday 16 February 1847. Image: ANNO.

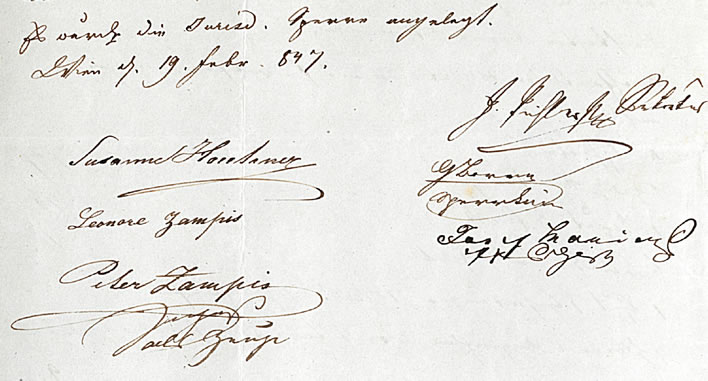

The inventory of effects of his estate was signed by Leonore and Peter Zampis and his oldest daughter, Susanna Höchner, who was then almost 39.

Detail of the signatures on the testamentary record for Conrad Höchner. Image: Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv.

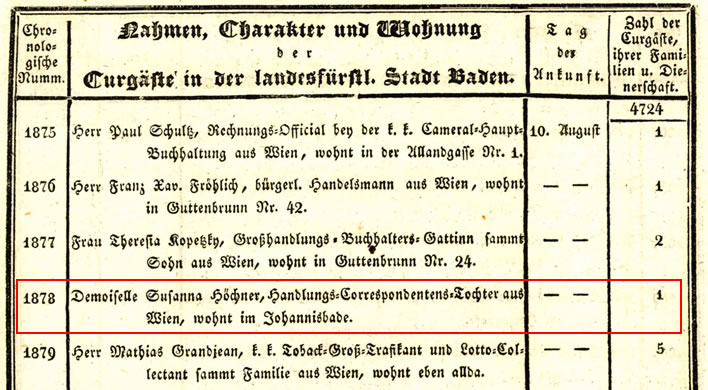

Susanna Höchner moves through the Höchner history almost invisibly. Castle makes no mention of her, as far as he is concerned Höchner had two sons and two daughters. During the stay in Nuit Saint Georges we hear nothing of her. We only discover her existence because of the birth entry (21 March 1808) in the Citizens' Register for Rheineck, but the subsequent silence might suggest that she died in childhood. Years later, however, she appears on the Conscription Record for the Höchner's apartment sometime after 1830. We read from the spa guestbook that she visited Baden bei Wien to take the waters there in August of 1833. She appears to have gone alone, which we might find surprising for a single woman at the time. In Heloise's letters from around this period, Eleonore is mentioned from time to time; Susanna never.

Guest list for the spa at Baden bei Wien in 1833. Image: ANNO.

Her surname is on her father's will in 1837 as 'Höchner', meaning presumably that she stayed single until then. Perhaps, like so many dutiful first-born daughters, she ended up looking after her widowed father and missed her moment of independence. Who knows? We need a lady novelist to sort this out.

Ferdinand Höchner, the second son, disappeared even more thoroughly than his sister Susanna. On a further page of Conrad Höchner's testamentary document the daughters stated that he was a Professor in Podolien, 'Professor in Podolia' a region of eastern Europe overlapping parts of Ukraine and Moldova, but, they note, die Stadt kann nicht angegeben werden, 'the town cannot be stated'. Readers who are still awake and sober will prick up their ears at the mention of Moldova: isn't this where Heloise's husband, another 'professor' came from? It seems a strange coincidence – you don't think brother Ferdinand did some matchmaking, do you?

Geneological summary

We can now replace Castle's superficially plausible but almost completely wrong summary of Heloise's origins with this one:

Conrad Höchner was born on 9 February 1776 in Rheineck, Canton St Gallen, Switzerland. He was the first child of Hans Conrad Höchner and his third wife Maria Girtanner. He married Maria Ursula Trachsler (b. 7?.02.1782, a Swiss girl from Alt/Neu St Johann in Toggenburg) in St Gallen on 25 November 1806. The couple had five children: Johannes Konrad (27 September 1804–12 January 1835), Ferdinand (13 March 1806–?) and Maria Susanna (21 March 1808–?) were born in Switzerland; Anna Sybille Heloise (9 March 1810–?, married on 3 December 1838 in Jassy) and Jeanne Éléonore (16 October 1814–22 June 1876, married on 21 February 1846 in Vienna) were born in Nuit Saint Georges. Maria Ursula Trachsler died in Nuit Saint Georges on 17 February 1815, aged 33. Conrad Höchner died on 12 February 1847.

Not as elegant as Castle's piece, but considerably more accurate. That is the great thing about archival research: when it works, it replaces fairy stories with facts.

Vienna

After this documentary excursion to establish at least a minimum level of knowledge about Heloise Höchner we can now return to the besotted pair we left in the summer sunset of the Kahlenberg in 1834.

Eduard Castle suggests that Grillparzer's finding a Heloise to his Abelard intrigued the mind of that literary chap. The cases could hardly be more different, though. The theologian Peter Abelard's (1079-1142) passionate love affair with Héloïse d'Argenteuil (1090-1164) became legendary in the account in the thirteenth century French epic poem Roman de la Rose. The details do not need to trouble us, but there was a child out of wedlock, a punishment castration and a retreat to a nunnery. Seize the day! indeed.

Grillparzer's Abelard dithered over his Heloise when he first saw her in that boat. 'Who knows? who knows?'. Readers will think back to another case of Grillparzer's dithering we discussed on this website some years ago, his poem Ständchen, 'Serenade', set to magnificent music by Franz Schubert. In that poem, the lover taps on the beloved's door but fails to wake him or her. Foregoing more energetic knocking, Grillparzer then rationalises that, in fact, sleep is really the best thing in the world to have and moves on – all thoughts of consummation repressed.

Admittedly Grillparzer was writing something that a choir of well brought up young ladies could sing, but Ständchen, as much as Begegnung, was a metaphor for Grillparzer's inability to seize the moment, retreating instead to limp dithering.

Heloise's boat, real or metaphorical, was rocking gently on the waves – all he had to do was jump in and this glorious Heloise, retroussé nose and all, would be his. Unfortunately for Heloise, jumping in to any kind of commitment was something the vacillating Grillparzer could never do. In the setting sun on the Kahlenberg the woods were all around them – Goethe wouldn't have hesitated a moment: carpe diem! Grillparzer, though, when the emotions became turbulent and he saw where things were inevitably going, did what he always did: he walked away. His psyche could cope with no further intensification.

He avoided even a farewell: he just dropped out of her life and avoided all further contact with her. Grillparzer could neither accept nor reject the goddess; once back in Vienna he simply ducked out of her reach, behind a curtain of social propriety.

We would know nothing of all this, were it not for another example of Grillparzer's vacillation. Grillparzer asked that his papers be destroyed on his death – a limp-wristed decision by someone who does not have the courage to destroy his own papers. For that task – the destruction of the artefacts of a life – would indeed require firmness and resolution. At his death in 1872 the documents remained unburned and to her great credit his 'eternal bride' Kathi Fröhlich left them intact for posterity. We wonder at this not a little, because, had Kathi read them, among those papers she would have found eight extraordinary letters written by Heloise to her milksop Abelard.

The letters came to light around 1924, during the work on August Sauer's edition of the Complete Works (many, many volumes, Anton Schroll, Vienna).

The reader will take from Heloise's letters what he or she brings to them. Cavaliers will be flexing their rapiers, itching to avenge the traduced girl; #metoo-ers will be metoo-ing (although there is no evidence that the milktoast Grillparzer ever laid a finger on her); Lotharios will be wondering quietly to themselves how else Grillparzer was supposed to flick this clingy piece of fluff from his sleeve.

Rebuffed

The 'inclination' between the two lovebirds had definitely been a holiday romance. What goes on in Heiligenstadt, stays in Heiligenstadt: on returning to Vienna Grillparzer cut Heloise dead. We don't know the exact form this took, but one way or another it became clear to the young woman that her new love never wanted to see her again. From what we read it appears that Grillparzer took even this decisive step indecisively: there was no last meeting – once home, Heloise was just ignored.

The conventions of the time forbade the dumped one to make contact with her dumper. Heloise, however, could not stand the lack of any closure, as we would express it these days, and was driven to write to Grillparzer. She did so in a letter dated 19 September 1834. After an initial apology for breaking the social taboo, she demanded an explanation from him for his behaviour:

I feel that only I can be the cause of your sudden retreat from a house that always received you with boundless respect and which was proud to see you here, everyone feels wounded by your behaviour and how much more painful must this neglect be for me.

Ich fühle daß nur ich die Ursache Ihres plötzlichen zurückziehen aus einem Hause sein kann daß Sie doch immer mit unbegrenzter Achtung empfieng, und stolz darauf war Sie bey sich zu sehen, alle fühlen sich durch Ihr Benehmen verletzt um wieviel mehr muß mich diese Hintansetzung schmerzlich berühren. [Ibid 93f]

The 'everyone' here is probably a reference to Mrs Stubenrauch and Aunt Theser, who appear to have undertaken some kind of matchmaking role to bring Grillparzer into the arms of the young woman who had made him so happy in Heiligenstadt. That attempt seems to have misfired badly and we suspect that Grillparzer may have spoken his mind to one or other of the dames, or more probably, poor Herr Stubenrauch.

Heloise's letters are a remarkable read in German, since they are written in a stream of consciousness of such authenticity that no artist could replicate it. Her favourite punctuation mark is the comma and her favourite conjunction 'and'. The translator has done his best to preserve this flowing urgency of thoughts being written down during their thinking.

What have I done to deserve that you flee me like this that has to make your earlier inclinations and respect so puzzling. Have you concluded because of the first [i.e. inclinations] that it would be better to avoid me, yet I cannot believe that I have ever given cause that you now withdraw the latter [i.e. respect]. I plead with you therefore for an explanation of your behaviour, which, as you would find yourself, has caused me the most indescribable unease.

Was habe ich aber verschuldet daß Sie mich auf eine Weise fliehen die mir Ihre früher bewiesene Neigung und Achtung höchst räthselhaft machen muß. Haben Sie sich wegen der ersteren besonnen und mich zu meiden für besser erachtet, so glaube ich daß ich nie einen Anlaß gegeben daß Sie letztere gegen mich ausser acht lassen. Ich bitte Sie daher sehnlichst um eine Aufklärung über Ihr Benehmen, was, wie Sie selbst finden werden, mich in die unaussprechlichste Unruhe versetzen muß. [Ibid ]

We now receive a hint of who the go-between in this misery is, for Heloise now tells us that it was Herr von Stubenrauch who was doing his ineffectual best trying to mollify Heloise over his star dramatist's abrupt rejection of her:

My fears have increased since eight days to a point where I cannot bear them any longer, the more Stubenrauch spoke in the most comforting terms of the undeserved slight, the louder were the voices within me demanding urgently to receive from you at least an explanation of such hurtful behaviour.

Meine Angst wuchs seit acht Tagen zu einem Grad, den ich nicht länger mehr ertragen kann noch will, je mehr St.(ubenrauch) über unverdiente Zurücksetzung wenn gleich in den schonendsten Ausdrücken, sprach, je lauter wurde die Stimme in mir wenigstens einige Aufklärung über ein so kränkendes Benehmen von Ihnen aufs Dringendste zu erbitten. [Ibid ]

Heloise is writing this letter on 19 September. Her remark that her fears have been growing over the last eight days might lead us to date the return to Vienna or at least the first hint she received of the separation from Grillparzer to around the 10th of that month.

In her flowing stream of consciousness style, Heloise describes her torments, those with which jilted lovers down the ages will be able to identify:

Every time the door bell rings I am in anxious, indeed desperate expectations of the entering person, and the deathly pallor that comes over me when I wait in vain and hope to remain undiscovered, as much as I try, by busily looking at my work. I could write endlessly more, if this does not move you, then the pride of the words inhibits me from saying more.

So oft nach Tisch die Thürglocke sich rührt bin ich in banger, ja krampfhafter Erwartung des Eintretenden, und die Toden-Bläße, die mich, wenn ich immer vergebens warte und hoffe überdeckt, weiß ich kaum, so sehr ich mich auch bemühe, durch ämsiges auf die Arbeit sehen, zu verbergen. Noch unendlich vieles wüßte ich hinzuzusetzen, doch wenn dieses Sie nicht bestimmt, hemmt mir der Stolz die Worte, Ihnen mehr zu sagen. [Ibid ]

From the above we begin to sense one of the main factors in her distress: the fact that neither her sister nor her father has any idea of the situation in which she finds herself – she busies herself in her work, since her emotional turmoil must remain a secret.

Once more, do not misunderstand these lines; it would not stand out if you were to pay people who hold you in such esteem a brief, long promised visit soon; where I would hope to have a chance to hear just a few words of explanation for your inexplicable hurtful behaviour towards me; even were they to be the last ever between us, they might give me hope back, that I have not been misjudged by you and thus would have in that respect at least my peace, which I need to have now more than ever.

Noch mal's, mißdeuten Sie diese Zeilen nicht; nicht auffallend wird es sein, wenn Sie Leuten die Sie so hoch schätzen einen kurzen längst versprochenen baldigen Besuch machen; wo ich dann hoffe Gelegenheit zu finden, nur einige aufklärende Worte, über Ihr mich nahmenloß kränkendes Benehmen gegen mich zu erfahren; seien sie auch die letzten zwischen uns, sie geben mir vielleicht die Hoffnung wieder, von Ihnen nicht verkannt worden zu sein, und dadurch in einer Hinsicht wieder meine Ruhe., deren ich mehr als je, eben jetzt bedarf. [Ibid ]

She concludes the letter with rhetorical power and with a signature undecorated by any conventional phrases that conveys the direct urgency of her text.

I am depending on the certainty of seeing you, you will not betray me and you will guide me back to that high esteem that I have always had for you and which I would want to lose for nothing on earth.

Heloise

Ich baue darauf Sie gewiß zu sehen, Sie werden mich nicht täuschen, und mich zu jener Hochschätzung zurückführen, die ich immer für Sie hatte und um keine Welt je verlieren möchte.

Heloise [Ibid ]

The next letter we have from Heloise to the silent Grillparzer is dated 7 October, that is, around eighteen days after her first letter. If the tone of the first letter was hurt anger, this letter is full of hurt pleading.

It is scarcely six o'clock in the morning and yet, although I am ill, restlessness has driven me out of my bed, I had today, exaggerated by physical suffering, a terrible night. I am using the moment when everyone else is asleep in order finally to put my feelings into words, for I have already written many letters and destroyed them.

Es ist 6 Uhr kaum, und dennoch trieb mich, ob gleich krank, die Unruhe aus dem Bette, ich hatte heute, noch mehr durch körperliches Leiden aufgeregt eine gar fürchterliche Nacht. Ich benütze den Augenblick wo Alles schläft, um endlich, denn viele Briefe schrieb ich schon und vernichtete sie wieder, meinen Gefühlen Worte zu geben. [Castle 95-97]

The gap of eighteen days between the letters can therefore be explained by the time spent writing letters that remained unsent – one more shared trait with the jilted down the ages. Grillparzer continues to keep his distance:

You leave my lines, the faithful description of my tortured pains, of my sickening heart, unanswered, for you send via a third party, who has no idea of this matter, a few bleak dry words, which do nothing to excuse your behaviour towards me, which cannot allay my fears nor can they be held to be an answer.

Sie ließen meine Zeilen, die treue Schilderung meiner quälenden Schmerzen, meines gekränkten Herzens unbeantwortet, denn daß Sie mir durch eine dritte Person die zwar nichts davon Ahnte, einige karge trockne Worte, die Ihr Betragen gegen mich doch nicht entschuldigen sagen ließen, das konnte wahrhaftig meine Angst nicht lindern, noch konnte ich es als eine Antwort gelten lassen. [Ibid ]

We now understand Grillparzer's ignoring technique of using a go-between to produce a cordon sanitaire between him and his Heloise. From what we have been told we might suspect that the unlucky go-between is in fact Philipp von Stubenrauch. If this is the case it is interesting that Heloise says this person 'has no idea of this matter', but unfortunately Heloise refers only to eine dritte Person, which allows both male and female.

I turn to you once more in writing, however much struggle and self-denial this step will cost me, I would have done this long ago, for my unease instead of reducing increases from day to day to an indescribable intensity, yet it always holds me back, I wanted the day that the world will see your new work, which was preceded by such days of worry and tiredness, to be finally over; up until then I had experienced every disturbance and disruption, also I could hardly believe I would have the composure, since the nearer the moment came the more disturbed and inconstant were my thoughts.

Ich wende mich daher noch einmal schriftlich an Sie, so viel Kampf und Selbstverläugnung mich dieser Schritt auch kostet würde ich ihn dennoch längst schon gethan haben, denn meine Unruhe statt sich zu mindern steigt von Tag zu Tag zu einer unbeschreiblichen stärke, doch immer hielt es mich zurück, ich wollte den Tag wo die Welt Ihr neues Werk sehen sollte, dem aber so mancher Tag voll Mühe und Ermüdung voran giengen, vorüber wissen; bis dahin hätte ich mir jede Störung zum Verbrechen gemacht, auch glaube ich kaum daß ich genug Sammlung gehabt hatte, denn je näher der Augenblick kam, je unruhiger und unstäter wurden meine Gedanken. [Ibid ]

The 'new work' was Der Traum ein Leben, 'The dream a life', inspired by the Spanish playwright Calderón's La vida es sueño, 'Life Is a Dream' (1635). It had its first performance on 4 October 1834 in the Burgtheater in Vienna. The present letter is dated 7 October. We note that, unlike Grillparzer's previous two plays, the latest one was enthusiastically received: 'new laurels are yours':

It is past, new laurels are yours; what I experienced how I rejoiced, how I suffered, where might I find the words to describe this to you; were you to know how I felt when I saw you again after eighteen long mortifying days, had you felt similar things, O! you would have certainly attempted to make good your error, whatever it cost you in effort. Through what have I deserved all this suffering, that you do not grant me a small short last conversation, it is so little and yet I would hope to be able to be calmer.

Es ist vorüber, neue Lorbeeren wurden Ihnen; was ich empfand wie ich jauchzte, wie ich litt, wo fänd ich Worte Ihnen dieß zu beschreiben; wüßten Sie was ich empfand als ich Sie nach 18 ewig langen tödtenden Tagen so wieder sah, hätten Sie ja änliches empfunden, o! gewiß, Sie würden Ihren Fehler zum Theil gut zu machen suchen, was es Ihnen auch für Überwindung kosten mag. Durch was habe ich die Leiden alle verdient, daß Sie mir auch nicht eine kleine kurze letzte Unterredung gönnen, es ist ja so wenig und doch hoffe ich dann ruhiger sein zu können. [Ibid ]

It appears from this part of the letter that Heloise attended a performance, probably the premier, since she saw Grillparzer there, 'for the first time in eighteen long mortifying days'. For the punctilious people trying to count to eighteen on their fingers we have to be clear: Heloise's first letter was written eighteen days before the present one, but her sighting of Grillparzer (if it was at the premier) occurred on 4 October, meaning that eighteen days will bring us to a few days before the first letter was written, which accords more or less with our initial suggestion of the date of the separation. Although therefore the precise timeline of Heloise's glimpses of her Abelard is unclear, we have no reason at all to doubt the accurate counting of a woman scorned – she would be counting in hours, not days.

You are fully convinced that I could not make you shake your decision, I hope on the contrary to find strength to strengthen you in your conviction, also do not worry that at the sight of you I will be overcome with weakness, the desire to spare you any unpleasant feelings will make me strong, you can be sure that I will hide every feeling, know how to repress every pain, I promise it, the thought of you gives me strength.

Sind Sie fest überzeugt, daß ich Sie gewiß in Ihrem Entschlüße nicht wankend machen werde, ich hoffe Kraft zu finden Sie im gegentheil darinn zu bestärken, auch fürchten Sie nicht, daß mich bey Ihren Anblick eine Schwäche überfällt, der Wunsch Ihnen jedes unangenehme Gefühl zu ersparen, wird mich stark machen, sind Sie überzeugt ich werde jede Gemüth- Bewegung zu verbergen, jeden Schmerz zurück zu drängen wißen, ich verspreche es, der Gedanke an Sie stärke mich. [Ibid ]

It appears that the go-between has informed Heloise that she has now been definitively dumped and that Grillparzer will have no more contact with her.

We twisted sceptics may be thinking that after what Grillparzer called the vollkommener Sukzess, the 'complete success' of the premiere of Traum had now put an end to the period of lukewarm recognition of recent years, the narcissist Grillparzer had no more need for Heloise's unconditional love and recognition that had buoyed him through those dark times – time to cast away the psychological crutch. To quote the great man himself: 'Who knows?'

Of these lines too no one will learn anything other than you and I, although it hurts me to have keep a secret from my good father and my worried sister. I anticipate after this repeated wish that it will be fulfilled, this time my hopes will not deceive me, it will not be conspicuous when you, since you promised Stubenreich, visit his wife; that I will be there cannot appear as anything but accidental, I thought Thursday at fourth-thirty; should this be inconvenient for you, I would ask you to send me a few lines on Wednesday at eleven o'clock, at this time I will be in the kitchen so that your lines can be received only by me.

Auch von diesen Zeilen soll niemand als Sie und ich je etwas erfahren, obgleich es mir weh thut vor meinen guten Vater und meiner bekümmerten Schwester irgend ein Geheimniß zu haben. Ich rechne nach dieser wiederholten Bitte auf deren Erfüllung, diesesmal werden Sie mein Hoffen nicht täuschen, nicht auffallend wird es sein wenn Sie, da Sie es doch St.(ubenrauch) versprachen, seine Frau ein mal besuchen; mein dazu kommen kann nicht anders, als Zufall erscheinen, ich dächte Donnerstag um 4½ Uhr; sollte es Ihnen so nicht genehm sein, so bitte ich Sie mir Mittwoch um 11 Uhr einige Zeilen zu schicken, ich werde um diese Stunde in der Küche sein, so daß nur ich Ihre Zeilen übernehmen kann. [Ibid ]

It becomes even clearer now how painful Heloise's position is. Not only has she been cast off in the most callous and brutal way, she is also hermetically sealed within a secret. Her father and her sister know nothing of what has happened; we hear of no friends in whom she can confide. Only the two ladies, Frau Stubenrauch and Aunt Theser have any idea of her situation.

Do not misunderstand these repeated steps, I could not command my restlessness my fear and all the feelings that torture me any longer, if I cannot survive your judgement seat, then how will I be able to survive before my own.

Vienna, 7 October. Heloise

Mißdeuten Sie diesen wiederholten Schritt nicht, ich konnte meiner Unruhe meiner Angst, und allen den Gefühlen die mich quälen nicht länger gebiethen, wenn ich vor Ihren Richterstühln nicht bestehe, wie soll ich es vor meinen eigenen.

Wien, den 7ten Oktober. Heloise [Ibid ]

Twenty-four days pass before Heloise writes to Grillparzer again, on 31 October 1834. After the anger and then the hurt of Grillparzer's behaviour comes self-abasement and martyrdom. We also learn that Heloise is still keeping the secret of her love for Grillparzer from her closest family.

Along with the books that you were so good to lend me I am sending you the slippers I promised you long ago. I could only half read the memoirs, but they serve as a means of sending you this little thing, which was actually intended to be sent on your name day, it comes a little late but it was impossible for me to finish them earlier, since I could only work on them in the moments when my sister was not at home and since I was also working in fear of discovery, my speed was reduced. I scarcely need to say that you must not think badly of this act, but unfortunately I am always afraid of being misunderstood by you, do no ask my why I do this, I cannot do otherwise, I have to obey the need to do something else other than merely occupy my thoughts with you.

Nebst den Büchern, die Sie so gütig waren mir zu leihen schicke ich Ihnen die längst versprochenen Pantofeln. Ich konnte die Memoiren leider nur halb lesen, doch sie müßen mir als Mittel dienen Ihnen diese Kleinigkeit, die eigendlich zu Ihren Nahmenstag bestimmt war zu senden, es kömmt zwar etwas spät doch war es mir unmöglich früher fertig zu werden, da ich nur in Augenblicken wo meine Schwestern nicht zu Hause waren, daran Arbeiten konnte und da noch mich (— mit) einer Angst überrascht zu werden die mir alle Schnelligkeit benahm. Kaum glaube ich sagen zu müssen daß Sie von diesen Thun nichts übles denken sollen, aber leider muß ich immer fürchten von Ihnen verkannt zu werden, fragen Sie mich nicht warum ich das thue, ich konnte nicht anders, ich mußte dem Drange folgen, mich auch anders, als bloß in Gedanken mit Ihnen zu beschäftigen. [Castle 97]

From the following we learn that Grillparzer is 'suffering', although the source of this information is not clear. Perhaps this was something the mediator (Stubenrauch?) told Heloise in order to appease her. It also appears that Grillparzer finally responded to her first letter and that Stubenrauch was indeed placed in the uncomfortable position of being the oral messenger in the middle.

You are, I hear, suffering, if only I could be given all your suffering; to take your pains upon myself, how infinitely willingly I would do that. Your answer to my first letter upset me deeply; after your previous conduct, this bitter step, could have been more gentle, over a sentence in it, and still other utterances, made to Herr von Stubenrauch, would have been easy to justify myself, but for that there is no time and I want to avoid the appearance of defending myself. I am under pressure, I could be discovered any minute, I promise you the greatest secrecy.

Sie sind, wie ich hörte, leiden(d), wäre es mir vergönnt all Ihr Leiden; Ihre Schmerzen, auf mich zu nehmen, wie unendlich gerne thät ich es. Ihre Antwort auf meinen ersten Brief kränkte mich tief; nach Ihren frühem Benehmen, hätte dieser herbe Schritt, wenigstens schonender geschehn können, über einen Satz darinn, und noch mehreren Äußerungen, gegen Herr v. St.(ubenrauch), wäre es mir leicht mich zu rechtfertigen, doch es gebricht mir an Zeit, auch will ich den Schein meiden, als wollte ich mich vertheidigen. Es drängt mich, ich fürch(t)e jede Minutte überrascht zu werden, ich beschwöre Sie um das größte Stillschweigen. Heloise [Ibid ]

Once again Heloise tells us of the extraordinary lengths to which she goes to keep her relationship with Grillparzer secret. Having written of her ability to defend herself she now prostrates herself docilely before her persecutor.