Isaiah the Obscured

Richard Law, UTC 2019-04-15 12:43 Updated on UTC 2019-10-30

Let's get all the untidy stuff out of the way before we start.

- Who was Isaiah?

- No idea. As far as we can tell, there may even have been two or three of them.

- When did he/they live?

- Oh, that's an easy one: possibly the eighth century BC – but that said, it may have been the seventh. Or perhaps the very end of the ninth. Or perhaps all three.

- Did he/they write his/their words out personally, or were they dictated or compiled at a later date from memory?

- Don't know.

- What do we have that he/they wrote?

- Strictly speaking, nothing. The Book of Isaiah that Jews and Christians find in their respective bibles comes from the so-called Masoretic text, which was written between 700 and 1000 AD, at least 1,700 years after its author(s) lived – that is, just before yesterday.

Well, that's a promising start by our standards. The last answer, though, needs a bit of qualification. That answer was correct up until 1946, when a Bedouin shepherd called Mohammed (can that strumpet Clio's sense of irony get better?) tumbled into a cave in Qumran and found an almost complete scroll of the Book of Isaiah that dated from around 300 BC.

That scroll and some other early finds were passed around and sold on: the greatest risk to the survival of the scrolls occurred not in the nearly two and a half millennia before their discovery, but in the two years from 1946 until 1948, when they were finally identified for the treasures they were.

Fortunately, the finders were honest Bedouin shepherds who were just trying to make a few groats from this strange and unreadable windfall to soften the otherwise scraping poverty of their lives. Had the scroll turned up in a medieval monastery the monks, without a second thought, would have snipped this mysterious heathen object up into small pieces for charms and votary offerings they could sell to the superstitious laity.

That one discovery extended the known history of the Isaiah text backwards by 1,300 years.

Book, scroll and chronicle

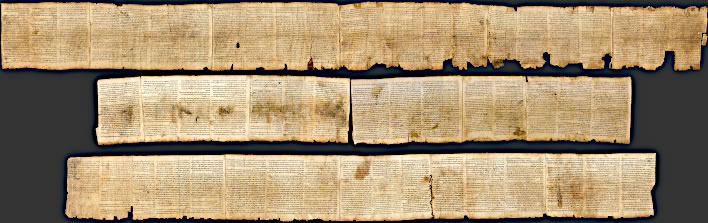

The 'Great Isaiah Scroll' from the Qumran caves. Image: Online zoomable version.

The remarkable thing about the find is that, despite being written centuries apart, the 'modern' Masoretic text is very similar to the ancient text of the Isaiah scroll from the Dead Sea caves. The discovery of the scroll therefore adds some validity to the Masoretic version. That is where we currently are with our Isaiah text: 300 BC.

Other fragments have been found here and there, but if we want to get back to the original Isaiah(s) and his/their original text(s), we still have to make a jump backward through the intervening darkness to the ninth/eighth/seventh century BC. Three centuries was a long time in that turbulent region.

In order to approach the Book of Isaiah in the right frame of mind we will have to work hard to shake off our modern preconceptions.

For us nowadays the Book of Isaiah is just one of the books of the Christian Old Testament or the Jewish Tanakh. But the texts we now find in these bibles were not written as integral parts of a single volume: it was the Masoretic scholars who first put together the Tanakh. As is the case with all of the texts that would later become 'books of the bible', Isaiah's text was an independent creation. No 'bible' existed of which it could be a book.

When we look at it in that sense and remove the brand name 'The Book of Isaiah', we are no longer worried by the probability of the existence of multiple authors or the many changes of narrative viewpoint in the document which seem to stem from different people in different periods of Jewish history.

We may usefully consider it as a chronicle which was incrementally extended by several hands over a period of possibly one or two centuries, a little like the chronicles that were created by monks in medieval European monasteries. We can reasonable imagine that it was subject to the effects of accretion, aggregation and commentary that we find so characteristic of Judaic documents in general.

The document would probably have been the property of a group of scholars or a school, which may have been copied many times. At some point one of the copies was hidden inside a large jar in a cave in Qumran. There were other copies to which the Masoretic scribes clearly had access, for only after their work on it was complete did it become the 'Book of Isaiah' and only then did the Jews have a Tanakh and only then did the Christians get their Old Testament.

Why read Isaiah?

The reader, having got this far without surrendering to slumber, may have found all this philological and textual hick-hack mildly interesting. But now comes the tough question: Why should we read Isaiah nowadays, this non-existent work of one or more non-existent prophets? Let's face it: we can reasonably expect that the biblical Book of Isaiah is not on the top of most people's reading lists.

Well, one or more of the Isaiahs did a lot to found Christianity – albeit with some help a few centuries later from Jesus, the writers of the gospels and the early fathers of the Church et al. When reading Isaiah, those whose memories of Christmas have been suffused with the carols and readings of Christianity will find many familiar phrases, echoes of Isaiah from the many quotations and paraphrases of him in the New Testament gospels.

The author(s) of the Isaiah text gave the new religion some historical validation, in that Jesus was the manifestation, the fulfilment of Isaiah's prophecies of the great renewer, the Messiah. Without that validation it seems likely that Christianity would have had an even more precarious start than it did. Instead of being marketed as Judaism 2.0 it would have been merely Jesusism 1.0.

If the Christians needed Isaiah to validate their presence, the Jews needed Isaiah to explain the historical disasters, one after another, that befell what was supposed to be the Chosen People. The repeated defeats, massacres, enslavements and sundry humiliations mustn't have left them feeling very 'chosen' at the time. Isaiah didn't blame God but the people – they had indeed been chosen, but had become unworthy of that status. Subsequent Jewish prophets took that line, too.

Furthermore, Isaiah's prophecies echo down the ages to the godless and decadent days of the present. The decadent Jews were going to get it in the neck from their God – deservedly so – and only a small remnant of them would be left after their enemies, God's instruments of his revenge, had finished with them. For us modern grumblers and dissentients Isaiah is definitely one of us.

Decline and fall

Reader, you may be one of the cool, age-of-reason atheists like the author who raises an eyebrow at the hellfire and damnation brigade. But like the author you should also recall the other great superstition that currently plagues us: the belief that mankind is chugging along empirical rails towards ever greater enlightenment progress – that every change and every innovation is to be welcomed and if something is new, it must be an improvement.

All the changes in modern western societies have come with that Hegelian/Marxist label of 'historical inevitability' stuck on them. That these are all inevitably 'progress' really is a fairy story. We grumpy cynics look at these barbarous innovations – the reader must make his or her own list – and think: How is that an improvement?

Technology may change the base and that in turn the superstructure, but those changes are not necessarily for the better. The author(s) of the Book of Isaiah would understand this. Civilisations collapse from within, usually with some help from without.

The Age of Gold and the crucible of refining

Nearly every historical civilisation has had some interpretation of the great ages of history: gold, silver, bronze and iron. The examination of the role of these ages in the ideations of historical cultures is a large and complex subject, one which we shall happily leave for another day.

For the moment, for our Isaiah understanding, we only need to note that the ages are a progression, with the current age, the current viewpoint, traditionally being located in the Age of Iron – or even worse, the Age of Clay. As James Joyce (1882-1941) put it masterfully in Ulysses (1922, Chapter 11, 'Sirens'): 'Gold by bronze heard iron steel'.

In this view we are looking backwards: there is a lost golden paradise that will never be regained by those currently living among the impurities, the debased alloys, of the present, the last age. It is a healthy and realistic position to take when you belong to a civilisation in decline that is steeped in corruption of all kinds.

There are, however, cheerful people who take the same structure of ages – gold, silver, bronze, iron – but reverse the clock. We may find ourselves in the coarse age of iron, but inevitable progress and the refinement of our alloys will ultimately take us to the age of gold – not the paradise we lost but the paradise we have yet to attain.

The author(s) of the Book of Isaiah conflate both of these historical models to give us a golden age at each end. The prophet rages against the decline of Israel from its earlier virtue:

See how the faithful city has become a prostitute! She once was full of justice; righteousness used to dwell in her — but now murderers!

Your silver has become dross, your choice wine is diluted with water.

Your rulers are rebels, partners with thieves; they all love bribes and chase after gifts.

AKJV (Authorised King James Version), Isaiah 1:21-23

This decline into the impure present – 'your silver has become dross' – brings with it consequences so severe that nearly everything that is now corrupt will have to be purged before the Age of Gold, the New Jerusalem, can be achieved once more. After this awful process of refinement in fire, the purity of gold will be achieved once again.

Every civilisation before ours has run its course and met its end – there is no evidence or reason to believe that ours is any different. The fatuous modern believes that because someone has developed radio, TV, cinema, social media and the smartphone we are ipso facto smarter than our ancestors. The rational ones among us see the great nations and empires of the Middle East and the Mediterranean basin rise and then fall as though in a time-lapse sequence. All cultures have always gone down after their ascendancy. Always.

The Jewish nation was almost obliterated, only to be reborn from the rubble of two millennia by an amazing fluke of history (as we atheists might put it), or by God's hand relenting (as Isaiah the far-seeing might put it). So the people who don't fall for this nonsensical idea, who see civilisations as intrinsically endangered unless they look after their own health – the remnant, as Isaiah would put it – need an Old Testament prophet's vocabulary. And for that, Isaiah is our man. Let's give him a read.

God's commission

We are going to start in Chapter 6 of the Book of Isaiah.

What did Chapters 1 to 5 do to be ignored? you ask.

Well, we shall get to them sometime, but it is a great mistake to take ancient texts in a strictly linear fashion. We think of modern books and scrolls and expect ancient texts to follow the same principles. Sometimes they do, but often they don't.

In the case of what we now call the Book of Isaiah, the ur-texts seem to have come from a number of hands. At some point they accreted into the scroll we now know as the 'Great Isaiah Scroll' from that Qumran cave.

If we try to read the work linearly, we are soon tearing our hair out at all the jumping about in time and the frequent changes of point of view. Old Testament prophets don't do orderly narratives – they have to take their visions as they come.

So if your are enthused by the current article to look up the Book of Isaiah in whatever form is appropriate to your faith, Jew, Protestant or Catholic, you are probably going to start speed-reading at about Chapter 3 and pack the whole enterprise in at about Chapter 5.

That would be a pity, because Chapter 6 is an important place to start. In it we learn of God's commissioning of Isaiah to his prophetic task.

'In the year that king Uzziah died' God appeared in a vision to Isaiah. That's putting it using the traditional, rather sanitised religious clichés. In fact God's arrival was fittingly, thunderously godlike:

And the posts of the door moved at the voice of him that cried, and the house was filled with smoke.

AKJV, Isaiah 6:4

Isaiah is a human being. Before he can deal with God he must be cleansed. That cleansing occurs in one of those passages of great symbolism that so ennoble the Jewish Tanakh and the Christian Old Testament, elevating them as literature from so many other ancient religious texts:

Then said I, Woe is me! for I am undone; because I am a man of unclean lips, and I dwell in the midst of a people of unclean lips: for mine eyes have seen the King, the Lord of hosts.

Then flew one of the seraphims unto me, having a live coal in his hand, which he had taken with the tongs from off the altar:

and he laid it upon my mouth, and said, Lo, this hath touched thy lips; and thine iniquity is taken away, and thy sin purged.

AKJV, Isaiah 6:5-7

In all the purgation rituals known to modern anthropology – and this is clearly one such – the chosen one transitions through a rite of passage involving the purgation of extreme pain to arrive at a state of purity.

Antonio Balestra (1666–1740), Profeta Isaia, ND. Image: Castelvecchio Museum, Verona, Italy

God is seeking a messenger to the Jews. Isaiah seemingly volunteers, but we know that in reality he as been chosen; he voluntarily underwent the excruciating purgation of the live coals on his lips before accepting the task. Only the acceptance of this awful rite of passage demonstrates the fanatical commitment required for the task ahead:

Also I heard the voice of the Lord, saying, Whom shall I send, and who will go for us? Then said I, Here am I; send me.

AKJV, Isaiah 6:8

Then God gives his commission to Isaiah. The commission itself is not easy to understand – but then, who expects the godhead to make himself easy to understand? This is how the AKJV renders what God tells Isaiah:

And he said, Go, and tell this people, Hear ye indeed, but understand not; and see ye indeed, but perceive not.

Make the heart of this people fat, and make their ears heavy, and shut their eyes; lest they see with their eyes, and hear with their ears, and understand with their heart, and convert, and be healed.

AKJV, Isaiah 6:9-10

What follows that great biblical invective of hearing without understanding and seeing without perceiving is a puzzle, however, both in the AKJV and in newer translations.

The root of that puzzle is the verb 'make', a command from God to Isaiah to cause the people of Israel not to see, hear or understand. That's a very strange thing to tell a prophet to do – prophets are supposed to put people on the right track, not sabotage their salvation. The Tanakh helps us out:

This people's heart is becoming fat, and his ears are becoming heavy, and his eyes are becoming sealed, lest he see with his eyes, and hear with his ears, and his heart understand, and he repent and be healed.

Tanakh, Yeshayahu 6:10

Now that makes more sense, particularly following the imprecation from Isaiah to understand and perceive. God is effectively saying to Isaiah: 'They won't listen to you'.

God already knows what is going to happen – a talent which is part of the divine job description, in fact – and he is simply warning Isaiah that the prophet is in for a long haul. Then follows the passage which is the summary of most of the Book of Isaiah:

Then said I, Lord, how long? And he answered, Until the cities be wasted without inhabitant, and the houses without man, and the land be utterly desolate,

and the Lord have removed men far away, and there be a great forsaking in the midst of the land.

But yet in it shall be a tenth, and it shall return, and shall be eaten: as a teil tree, and as an oak, whose substance is in them, when they cast their leaves: so the holy seed shall be the substance thereof.

AKJV, Isaiah 6:11-13

So Isaiah (or his message) will have to continue until Israel has been almost extinguished – even when only a tenth remains, more will still be obliterated. From this seemingly dead trunk, as the 'teil tree', the terebrinth (the turpentine tree, a favourite in biblical iconography, here presumably because of its remarkable fragrance, its 'essence' which 'shall be the substance thereof') and the gnarled, deep-rooted oak show us, the 'remnant' will arise again with the 'holy seed' still within them.

The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God.

AKJV, Isaiah 40:3

Is Isaiah's mission completely futile?

No. He is there to speak to the remnant, those few who will survive after the apocalyptic destruction of Israel. We now perceive the deeper metaphor of the purging coal on Isaiah's lips, T.S. Eliot's 'refining fire'. It is indeed deeply metaphoric: not only will Isaiah be purged and made ready for the divine end state, the whole of Israel is about to be purged in fire and suffering, the silver will be freed from its dross in the crucible of Jewish history.

Watching Israel burn

The main instrument of destruction at first is the vast, emergent power of Assyria. Even after Assyria has declined and fallen, Israel finds itself under the yoke of yet another persecutor: Babylon. 'By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion' [AKJV Psalms 137:1].

Finally, when the tree of the Jews is bare of leaves, new, righteous life will spring up from the stumps.

Watchman, what of the night? Watchman, what of the night? The watchman said, The morning cometh, and also the night.

AKJV, Isaiah 21:11

Isaiah's great task is the recovery of some Jewish golden age from the corruption of the present. His messages contain nothing new, but merely imprecations and appeals for a return to former and accepted values:

Have ye not known? have ye not heard? hath it not been told you from the beginning?

AKJV, Isaiah 40:21

That re-establishment will involve immense destruction until Israel can be reborn at the start of a new golden age. Amongst the destruction, therefore, there is a vision of the re-establishment of Zion and the new world order that follows that.

Heralding the destruction

Throughout the Book of Isaiah, stick and carrot alternate. This is one of the features that makes the text such a difficult linear read.

The sticks are the magnificent prophecies of doom and destruction that even we moderns still partially remember. Since we are not making a careful exegesis of the text we can restrict ourselves to recalling just a few of those memorable condemnations that have passed into the English language from Isaiah's 66 chapters:

- Bring no more vain oblations; incense is an abomination unto me; the new moons and sabbaths, the calling of assemblies, I cannot away with. [AKJV 1:13]

- What mean ye that ye beat my people to pieces, and grind the faces of the poor? [AKJV 3:15]

- And he looked for judgement, but behold oppression; for righteousness, but behold a cry. [AKJV 5:7]

- Woe unto them that join house to house, that lay field to field, till there be no place. [AKJV 5:8]

- Woe unto them that call evil good, and good evil. [AKJV 5:20]

- And the wild beasts of the islands shall cry in their desolate houses, and dragons in their pleasant palaces. [AKJV 13:22]

- Let us eat and drink; for tomorrow we shall die. [AKJV 22:13]

- We have made a covenant with death, and with hell are we at agreement. [AKJV 28:15]

- Speak unto us smooth things, prophesy deceits. [AKJV 30:10]

- The bread of adversity, and the waters of affliction. [AKJV 30:20]

- And thorns shall come up in her palaces, nettles and brambles in the fortresses thereof: and it shall be an habitation of dragons, and a court for owls. [AKJV 34:13]

- Set thine house in order: for thou shalt die, and not live. [AKJV 38:1]

- I shall go softly all my years in the bitterness of my soul. [AKJV 38:15]

- The nations are as a drop of a bucket, and are counted as the small dust of the balance: behold, he taketh up the isles as a very little thing.[AKJV 40:15]

- Woe unto him that striveth with his maker! Let the potsherd strive with the potsherds of the earth. Shall the clay say to him that fashioneth it, What makest thou? [AKJV 45:9]

- There is no peace, saith the Lord, unto the wicked. [AKJV 48:22]

- All our righteousnesses are as filthy rags; and we all do fade as a leaf. [AKJV 64:6]

We grumblers and malcontents should have these phrases by heart, for scarcely a day passes without some fitting reason to shout out one or more of them.

Heralding the new age

Interspersed with the prophecies of doom and destruction are the great messages of hope. They are an uplifting view in the the golden age that is yet to come after the devastation of the purgation. Here are just a few examples:

- Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be as white as snow. [AKJV 1:18]

- They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruninghooks: nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any more. [AKJV 2:4]

- The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light: they that dwell in the land of the shadow of death, upon them hath the light shined. [AKJV 9:2]

- The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them. [AKJV 11:6]

- And the lion shall eat straw like the ox. And the sucking child shall play on the hole of the asp, and the weaned child shall put his hand on the cockatrice' den. They shall not hurt nor destroy in all my holy mountain: for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea. [AKJV 11:7]

- In this mountain shall the Lord of hosts make unto all people a feast of fat things, a feast of wine on the lees, of fat things full of marrow, of wine on the lees well refined. [AKJV 25:6]

- He will swallow up death in victory; and the Lord God will wipe away tears from off all faces. [AKJV 25:8]

- In quietness and in confidence shall be your strength. [AKJV 30:15]

- Then shall the lame man leap as an hart, and the tongue of the dumb sing: for in the wilderness shall waters break out, and streams in the desert. [AKJV 35:6]

- They shall obtain joy and gladness, and sorrow and sighing shall flee away. [AKJV 35:10]

- Comfort ye, comfort ye my people, saith your God. Speak ye comfortably to Jerusalem, and cry unto her, that her warfare is accomplished. [AKJV 40:1]

- The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Every valley shall be exalted, and every mountain and hill shall be made low: and the crooked shall be made straight, and the rough places plain: And the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together: for the mouth of the Lord hath spoken it. [AKJV 40:3]

- He shall feed his flock like a shepherd: he shall gather the lambs with his arm, and carry them in his bosom, and shall gently lead those that are with young. [AKJV 40:11]

- But they that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength: they shall mount up with wings as eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not faint. [AKJV 40:31]

- How beautiful upon the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings, that publisheth peace; that bringeth good tidings of good, that publisheth salvation; that saith unto Zion, Thy God reigneth! [AKJV 52:7]

- For they shall see eye to eye, when the Lord shall bring again Zion. Break forth into joy, sing together, ye waste places of Jerusalem: for the Lord hath comforted his people, he hath redeemed Jerusalem. [AKJV 52:8]

- Instead of the thorn shall come up the fir tree, and instead of the brier shall come up the myrtle tree. [AKJV 55:13]

- Is not this the fast that I have chosen? to loose the bands of wickedness, to undo the heavy burdens, and to let the oppressed go free, and that ye break every yoke? [AKJV 58:6]

- Then shall thy light break forth as the morning, and thine health shall spring forth speedily. [AKJV 58:8]

- Arise, shine; for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee. [AKJV 60:1]

- And they shall build the old wastes, they shall raise up the former desolations, and they shall repair the waste cities, the desolations of many generations. [AKJV 61:4]

Admittedly, most of the above do not really fit the current mood. It is useful to have a few ready, though, just in case a meteorite strikes the international headquarters of Greenpeace – which, one day, must happen. Have faith, have faith.

Heralding the Messiah

It is unsurprising that the New Testament gospels that relate some aspect of the Nativity give us an account that appears to be largely tailored to Isaiah's prophecies. In the Book of Isaiah the early Christians saw what they wanted to see in the manner that they wanted to see it. It was politically essential for them to produce evidence for their assertion that Jesus was the Messiah, the Immanuel, whose appearance Isaiah had foretold all those centuries before.

- Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel. [AKJV 7:14]

- For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace. Of the increase of his government and peace there shall be no end. [AKJV 9:6]

- And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots: And the spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him, the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of counsel and might, the spirit of knowledge and of the fear of the Lord. [AKJV 11:1]

- He hath no form nor comeliness; and when we shall see him there is no beauty that we should desire him. He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not. Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows. [AKJV 53:2]

- But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed. All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way; and the Lord hath laid on him the iniquity of us all. He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he opened not his mouth: he is brought as a lamb to the slaughter, and as a sheep before her shearers is dumb, so he openeth not his mouth. [AKJV 53:5]

- He was cut off out of the land of the living. [AKJV 53:8]

- He was numbered with the transgressors; and he bare the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors. [AKJV 53:12]

It is striking that Isaiah's saviour of the Jews was not a warlike figure. Today we would characterise the figure of the Messiah as 'vulnerable', one 'despised and rejected of men'. The Jewish rebirth when it would come would be a moral not a military rebirth.

Everything that Isaiah says about the golden age to come is a message of peace. The violent disasters that would successively crash over Israel were a process of purgation that would remove the many sinners and leave the righteous to live in peace – the lion would lie down with the lamb, etc. Even this strange, helpless, vulnerable Messiah will be 'brought as a lamb to the slaughter'. Isn't this the most remarkable text to find emerging from the tumult of those centuries?

Isaiah prophesies the coming of a saviour, of 'David's line', who would restore the lost virtue of Israel. At this moment the separate strands of early Christian theology and Jewish rebirth intertwine, but they remain as two quite distinct messages. The message of the Jewish strand was that, according to Isaiah, the Messiah would be the saviour of the Jews and the founder of the new Golden Age of the New Jerusalem – a task that, with the benefit of two millennia of hindsight, we realise didn't quite pan out as it was supposed to. There's still time, though.

Expiating the Fall of Man

In contrast, the message of the Christian strand is not about the destruction and rebirth of the tribes of Israel – the Christian church could not care less about them. For Christians Isaiah represented the period between the catastrophe of the Fall of Man and the second chance offered by the coming of Jesus Christ the Redeemer. The first lines of John Milton's epic Paradise Lost are the executive summary of the period:

Of Mans First Disobedience, and the Fruit

Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal tast

Brought Death into the World, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, till one greater Man

Restore us, and regain the blissful Seat,

John Milton, Paradise Lost (1667;1674): Book 1, 1-5.

From this point of view, the arrival and the ultimate death of Jesus, 'one greater Man', was the sacrifice which expiated the devastating error that led to the Fall of Man. That is why the angel in Michelangelo's famous image of Isaiah from the Sistine Chapel is pointing back to the depiction on the central ceiling of the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden.

Michelangelo (1475-1564), Isaiah (1509). Part of the Sistine Chapel ceiling in the Vatican, Rome. The ceiling was restored between 1979 and 1994/9. Some (your author included) believe this restoration was very badly executed. Centuries of grime were removed, but so were many important details of the paintings, most crucially and most frequently the eyes of many of the figures. The restored image almost makes Isaiah look blind. This photograph of Michelangelo's Isaiah was taken before the restoration took place.

This is a popular and often reproduced image for good reason; every part of it demonstrates Michelangelo's genius in some way. For only one example, consider the anxious expression on the face of the putto standing at the back, the partial face just visible under the arm of the putto in the foreground. Consider how much this small detail contributes to the feeling of urgency behind the image as a whole.

The three creation panels – the creation of Adam, the creation of Eve and the expulsion from the Earthly Paradise – are located at the very centre of the entire ceiling. This is a photo is of the restored ceiling, so don't bother to look more closely.

The panel with the image of Isaiah in its context in the ceiling. The red line runs from the putto's pointing hand to the scene of the expulsion from Paradise.

Desemitising Isaiah

By the time that Michelangelo (1475-1564) was dabbing around on the Sistine Chapel ceiling (1508-1512), Isaiah's mission statement had been transformed into the prophecy of the coming of the Christian redeemer, who through his sacrifice would purge that original sin. The rest of Isaiah's text was just Jewish noise.

1509 – lest we forget. Thirty years before Michelangelo's 'Isaiah' was painted, the Catholic Inquisition hit its persecutional stride. It alone would leave at least 30,000 Jews dead. In the ten years or so before Michelangelo climbed the scaffolding with his brushes all – all – the Jews in Spain were exiled (1492); ditto from the Duchy of Austria (1496); ditto from Portugal (1497). The absence of all that is Jewish about this representation of one of the Jew's greatest prophets is the silent witness of yet one more great catastrophe in the history of the Jewish people.

Emilio Sala y Francés, The Expulsion of the Jews from Spain, 1889. The Grand Inquisitor, the Dominican Torquemada, throwing a crucifix on the table and demanding the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, before Ferdinand II (1452-1516) and his wife Isabella I (1451-1504). Image: Museo Nacional del Prado.

There is, too, the great irony that the Jewish prophet who laid the foundations for the new religion thus founded what would become its greatest persecutor, bar none. But Isaiah's vision of the New Jerusalem, that Jerusalem the Golden, stayed with the Jews during two and a half millennia of oppression, diaspora and persecution.

Jeremiah followed Isaiah, amplifying his predecessor's lamentations, which then went into the Book of Psalms and in that famous asseveration of the vision of the coming Jewish Golden Age, even when seen in Babylonian exile, Psalm 137:

If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.

If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth; if I prefer not Jerusalem above my chief joy.

AKJV, Psalms 137:5-6

As an aside: Heinrich Heine put a wonderful paraphrase of these two verses into the mouth of the Jewish medieval poet and scholar Jehuda ben Halevy (Judah Halevi 1075?-1141): Lechzend klebe mir die Zunge / An dem Gaumen, und es welke / Meine rechte Hand, vergäß' ich / Jemals dein, Jerusalem. 'May my tongue stick to the roof of my mouth and may my right hand shrivel should I ever forget you, Jerusalem'. [Heinrich Heine, Romanzero, 'Jehuda ben Halevy']

Pope Julius II, the painter's employer, would have approved of Michelangelo's portrait of Isaiah. It is theologically sound. The Old Testament prophet is represented with the head of someone you could see any day – even today – on a Roman street, the image has been desemitised: no beard and flowing, colourful classical robes in a classical architectural setting. The head is not dissimilar to that other Italianate Jew created by Michelangelo only a few years before, his statue of David (1504).

Michelangelo's Isaiah is holding a great book, not a scroll, the sort of thing you might find in the Vatican Library. His little finger is marking the page he was reading before he was interrupted by the urgent clamour of the putto.

There is a remarkable absence of biblical detail, especially the hot coal, an incident which one would have thought would have been a perfect dramatic image, just as did Antonio Balestra.

Michelangelo – certainly in later life – was a pious believer, but whether he was an avid reader of the Book of Isaiah in the Vulgate bible is an open question. The only certain thing is that he did what his patron required and absorbed this Jew fully into the Christian world.

The truly astonishing thing, though, is that millions of visitors can crick their necks to look at that great image of Isaiah, and millions more gaze with pleasure on its digital version on the internet, but we never hear anyone ask: 'Where's the Jew?'

Conclusion

For the modern person the Book of Isaiah has much to offer. It is a fine account that applies to the corruption and pollution of the current age, the dross which will only end when the earth has been totally cleansed. Only then will the new Golden Age be attained.

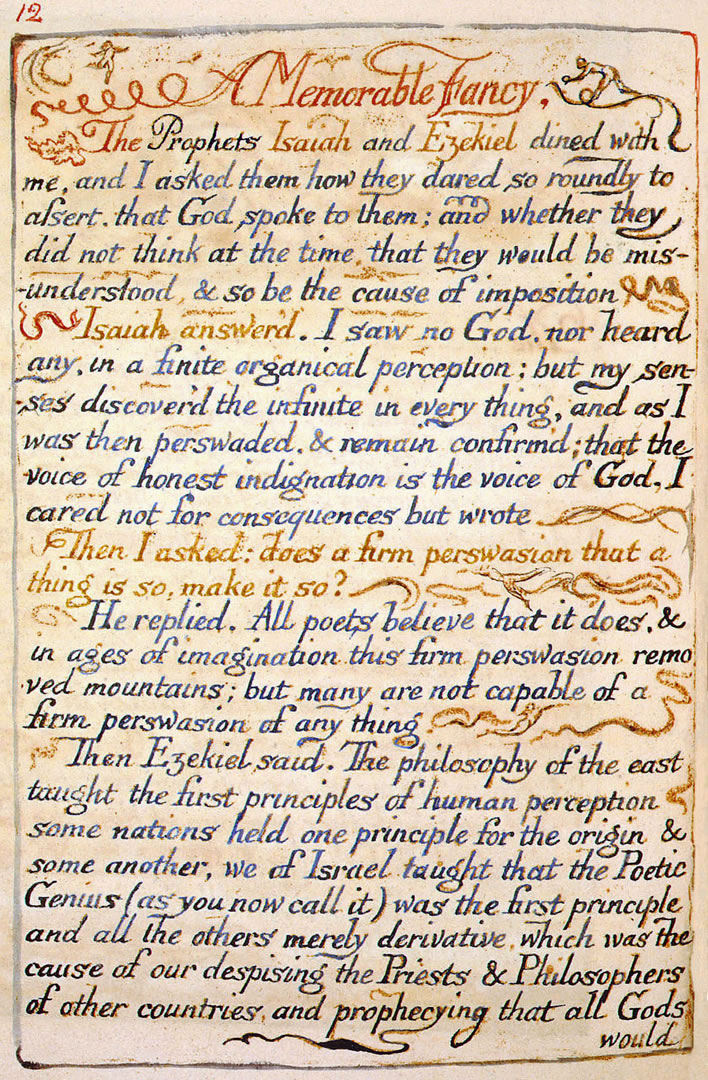

That great English grumbler, malcontent and visionary William Blake (1757-1827) had the opportunity to speak to Isaiah in person, as recounted in Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790-93). Blake asked him the sceptic's question, the one we all want to ask:

A Memorable Fancy,

The Prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel dined with

me, and I asked them how they dared so roundly to

assert. that God spoke to them; and whether they

did not think at the time, that they would be mis-

-understood, & so be the cause of imposition,

William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

That troublemaker Isaiah, recognizing in Blake a fellow traveller in troublemaking, gave him the prophets' answer, the one we all want to give:

Isaiah answer'd. I saw no God, nor heard

any, in a finite organical perception; but my sen-

-ses discover'd the infinite in every thing, and as I

was then perswaded. & remain confirm'd; that the

voice of honest indignation is the voice of God, I

cared not for consequences but wrote.

Then I asked: does a firm perswasion that a

thing is so, make it so?

He replied. All poets believe that it does, &

in ages of imagination this firm perswasion remo

-ved mountains; but many are not capable of a

firm perswasion of any thing.

Ibid.

The 'voice of honest indignation', 'I cared not for consequences but wrote'… 'but many are not capable of a firm perswasion of any thing.' That sounds about right.

Blake's 'Memorable Fancy' of his dinner with the prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel. Image: Blake Archive.

That other purgation, Noah's Flood, drowned every living thing except the tiny remnant of the righteous and the innocent in the ark. The inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah, against whom Isaiah also rails in Chapter 1, were all obliterated save for that tiny incestuous remnant, Lot and his daughters. What remnant will be left this time round and will you, reader, be one of its tiny number?

Update 30.10.2019

Either Michelangelo saw the film The Godfather (1972) or Francis Ford Coppola, its director, had some deep memory of Michelangelo's Isaiah on the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

Salvatore Corsitto and Marlon Brando in The Godfather (1972), directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Image: © 1972 Paramount Pictures Corporation.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!