Quote and image of the month 09.2019

Richard Law, UTC 2019-09-17 13:02

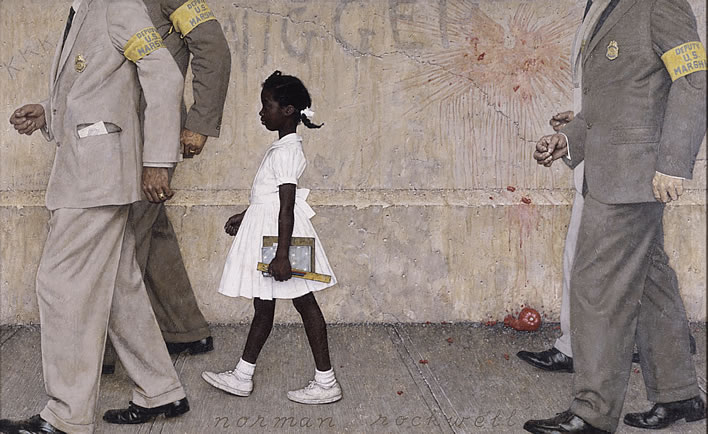

Norman Rockwell, The Problem We All Live With (1964)

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), The Problem We All Live With, 1964. The painting was originally published as a centerfold in the 14 January 1964 issue of Look. Image: ©Norman Rockwell Museum. [Click on the image to view a larger version in a new browser tab.]

In 1954 the United States Supreme Court in 'Brown v. Board of Education' ruled that state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students were unconstitutional.

Rockwell's painting depicts the moment when Ruby Bridges, a six-year-old African American girl, had to be escorted by four deputy U.S. marshals to and from William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, an all-white school, on 14 November 1960.

Unfortunately, the subtleties of Rockwell's carefully thought-out imagery are largely swamped in the deluge of social-justice hysteria that submerges this painting.

Readers might consider Rockwell's almost identical rendering of the marshals and the peculiarity of their gait – knees bent, arms in the same position and in step. Ruby's position in the painting is not in the centre as one might expect, but on the left-hand golden section, giving the impression that this young girl is moving forwards eagerly, such that she is driving the group forwards, not sheltering within it. Her demeanour expresses determination: back straight and head held high, her school things carried openly in her hand, not hidden in a bag.

The leading marshal has what appears to be a legal document in his pocket, the kind of detail that is one of Rockwell's artistic trademarks. The background of the picture is a plain wall, the graffiti and stains on which tell us of the historical and political background to the scene, the long-lasting conflict over the desegregation of schools.

Ruby's white dress is a fiction of Rockwell's. Unlike the marshals, her legs are straight and her stride even, meaning that the strange gait of the marshals may indicate that they have slowed their pace to accommodate the walking speed of the six-year-old girl, or perhaps, in contrast to the girl's firm stride, it may indicate hesitancy. Once again, Rockwell the master observer at work.

The subtleties of the title of the work are too often ignored. The title does not scream a particular message at the observer but frames the image with enlightened understatement that allows the painting to speak for itself: [the problem] – [we all] – [live with].

The press accounts and photographs of the epochal event have long since passed over time's waterfall; Rockwell's painting is still with us.

Rudolf Hagelstange, Bei den schwarzen Baptisten / Among the black Baptists (1962)

In Charlottesville,

in Virginia,

I met, among the black Baptists,

the friendliest Christians for a long time.

I already saw one at the church door waiting

for me and had to fill in one of the cards:

Name, Address, Country of Origin —

and whatever else was on the card.

Then a girl in a snow-white dress showed

me to a place, not far

from the (sort of) stage

bent into a semicircle, in front of it a lectern;

behind it, raised on a platform,

three rows of the choir, who just then appeared,

soon followed by Reverend Green.

In Charlottesville,

in Virginia,

traf ich, bei den schwarzen Baptisten,

seit längerer Zeit die freundlichsten Christen.

An der Kirchentür sah ich schon einen warten

auf mich und musste eine der Karten

ausfüllen: Name, Adresse, Herkunftsland —

und was noch sonst auf der Karte stand.

Dann brachte ein Mädchen in schneeweissem Kleid

mich an einen Platz, nicht weit

von der (gewissermassen) Bühne,

im Halbkreis geschwungen, vorn ein Podest;

dahinter, erhöht wie auf einer Tribüne,

drei Reihen des Chors, der eben erschien,

bald gefolgt von Reverend Green.

First the choir sang and then the congregation.

The black Mister Green greeted his friends

and prayed simply and without a book,

just as the words came from his heart.

And they all listened to the quiet speech;

he spoke for everyone there.

They sang and then the man of God began

to preach.

Erst sang der Chor und dann die Gemeinde.

Dann grüsste der schwarze Herr Grün seine Freunde

und betete einfach und ohne Buch,

wie ihm die Worte vom Herzen fielen.

Und sie lauschten gesammelt der leisen Rede;

er sprach ja für jeden und jede.

Sie sangen, und dann fing der Gottesmann

zu predigen an.

He spoke of Love, the divine light,

that breaks into our human darkness.

He spoke not as a righteous man to sinners.

He spoke as a father to his children.

He spoke of the light of the sun and then

from artificial light: the way Mother poured the oil

into the lamp, and how then

gas was invented, electricity

and the neon light. — 'But my soul', —

he called out —, 'Whatever humans can now do, —

there is a long, long path to travel,

until they have invented a light that

is a bright as the sun and is so beautiful!'

Er sprach von der Liebe, dem göttlichen Licht,

das in unser menschliches Dunkel bricht.

Er sprach nicht wie ein Gerechter zu Sündern.

Er sprach wie ein Vater zu seinen Kindern.

Er sprach von dem Lichte der Sonne und dann

von dem künstlichen Licht: wie die Mutter das Öl

auf die Lampe gegossen, und wie man dann

das Gas erfunden, die Elektrizität

und das Neon-Licht. — «Aber meiner Seel», —

rief er da —, «was der Mensch auch kann, —

da ist noch ein lang-langer Weg zu gehn,

bis sie ein Licht erfinden werden, das

so hell wie die Sonne ist und so schön!»

And they nodded at each other.

And they beamed at him:

Right, Sir! That's true!

Und sie nickten sich zu.

Und sie strahlten ihn an:

Right, Sir! That's true!

And then

the Reverend spoke of the inner light,

that which only

shines from the eyes as

a trace,

but which lights up spaces, many spaces of the world

with one ray.

Und dann

sprach Reverend von dem inneren Licht,

das eben nur

aus den Augen bricht

eine Spur,

aber Räume, viele Räume der Welt

mit einem Strahle erhellt.

And they nodded at him

and smiled sagely.

And said: Oh, Yes!

But quietly.

Und sie nickten ihm zu

und lächelten weise.

Und sagten: Oh, Yes!

Aber leise.

'There are also people who hang

their lamps outside — yes, indeed — and force

a light on others; yet there is not a trace

of light in their own room!'

And Reverend took the lamp in his hand,

that stood in front of him,

and held it at the side low down:

'So! Do you see that? So!'

«Hingegen gibt es auch Leute, die hängen

ihre Lampen nach draussen — jawohl — und drängen

andern ein Licht auf; doch ist da kein Schimmer

von Licht in ihrem eigenen Zimmer!»

Und Reverend nahm die Lampe zur Hand,

die da vor ihm stand,

und hielt sie tief seitlich:

«So! Seht Ihr? So!»

And then they even laughed

and nodded to each other

and were so happy,

that such a murky case was now so clear

to be seen from the example of the lamp and

Reverend Green's words.

Oh, Yes. That is true!

Und da lachten sie gar

und nickten sich zu

und waren so froh,

dass dieser so trübe Fall nun so klar

von dem Beispiel der Lampe und

Reverend Greens Mund abzulesen war.

Oh, Yes. That is true!

And then the black Mister Green praised

the flowers, which bloom in the sun

just like all good and quiet deeds,

which bring us into the light of Love,

and how they bring others to light up

and penetrate us with their light.

And then he sang his song of the sun

and raised his arms and said thanks

for the doubled sun, which glowingly permeates all those,

who only see it.

Und dann rühmte der schwarze Herr Grün

die Blumen, die an der Sonne erblühn

wie alle guten und stillen Taten,

die uns im Lichte der Liebe geraten,

und wie sie die andern zum Leuchten bringen

und uns selber mit ihrem Lichte durchdringen.

Und dann sang er seinen Sonnengesang

und hob seine Arme und sagte Dank

für die doppelte Sonne, die jeden durchglüht,

der sie nur sieht.

And the words sprang like glowing coals

from his mouth. Soon he spoke quickly;

then he faltered

and searched for the right word.

And when it came to him he tossed it towards them.

And they caught it.

Or called it out to him.

And said: Oh, Yes.

And: That's right, Sir. That's true!

Und es sprangen die Worte wie glühende Brocken

von seinem Munde. Bald sprach er schnell;

dann geriet er ins Stocken

und suchte nach dem treffenden Wort.

Und hatte ers, warf er es ihnen zu.

Und sie fingen es auf.

Oder riefens ihm zu.

Und sagten: Oh, Yes.

Und: That's right, Sir. That's true!

Then he closed his Bible.

And spoke for everyone a short prayer,

already wrapped in the sound of the organ.

And then they sang out their longing

for Zion's golden house still to come.

Dann klappte er seine Bibel zu.

Und sprach für alle ein kurzes Gebet,

schon von den Klängen der Orgel umweht.

Und dann sangen sie ihre Sehnsucht aus

nach Zions goldenem Zukunftshaus.

At the end Reverend Green said:

'At my feet are sitting

two white guests. Let us greet them.' —

A female name was mentioned first.

I looked around. A lady stood there,

smiling kind-heartedly, goodness itself.

The sun broke through and in her radiance

she looked like the Franciscan sister.

And then my name was spoken. They were astonished

at the Mister from Germany.

That was scarcely to be believed: Yes, just look, look!

He had a long way to come to get to church here!

Three thousand miles over the ocean alone…

Zum Schlüsse aber sprach Reverend Green:

«Es sitzen mit euch zu meinen Füssen

zwei weisse Gäste. Wir wollen sie grüssen.» —

Es fiel zunächst ein weiblicher Name.

Ich sah mich um. Da stand eine Dame,

grundgütig lächelnd, das Wohltun selbst.

Die Sonne brach ein, und in ihrem Glanz

sah sie aus wie die Schwester vom heiligen Franz.

Und dann fiel der meine. Da staunten sie

über den Mister aus Germany.

Das war kaum zu glauben: Ja, schaut nur, schaut!

Hat der einen weiten Kirchweg daher!

Dreitausend Meilen allein übers Meer…

And they nodded at me

and smiled sagely

and said quietly:

God bless you…

Und sie nickten mir zu

und lächelten weise

und sagten leise:

God bless you…

Rudolf Hagelstange (1912-1984), Bei den schwarzen Baptisten, 'Among the black Baptists', in Lied der Jahre, Gesammelte Gedichte 1931-1961, Frankfurt/Main, 1962. Translation ©Figures of Speech 2019, reuse in whole or part only with link to this page.

Rudolf Hagelstange was born in the town of Nordhausen in Thuringia to middle-class, Catholic parents in 1912. Between 1931 and 1933 he studied Philology in Berlin; the rest of the thirties he spent in travel and local journalism.

The war caught up with the 28-year-old in 1940, when he became a frontline war reporter in France and Italy. It was in northern Italy that he was captured and imprisoned near the end of the war by the American forces. He was released at the end of 1945.

The members of his family were decidedly anti-Nazi: in 1944 his father was imprisoned in the Buchenwald concentration camp for his views. After the war Nordhausen became part of Eastern Germany and shortly thereafter Hagelstange wisely left the DDR to its own devices and began a literary career in the West, which included much travel. He travelled to the USA in 1954 at the invitation of the US State Department. He died in 1984 and is buried in Erbach.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!