Quote and image of the month 12.2019

Richard Law, UTC 2019-12-16 07:13

Jules Bastien-Lepage, The Annunciation to the Shepherds (1875)

Jules Bastien-Lepage, L'Annunciation aux bergers / The Annunciation to the Shepherds, 1875. Image: National Gallery of Victoria [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab.]

Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884) died in his studio in Paris, only 36 years old, on 10 December 1884, 135 years ago. He had been in poor health for some years, succumbing in the end to an abdominal tumour.

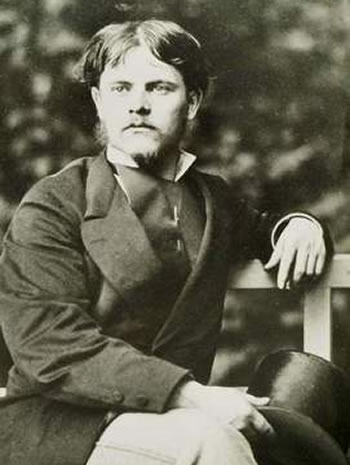

Jules Bastien-Lepage, ND.

Despite his humble origins his pure talent and independent cast of mind brought him far as a painter in his short life.

He is remembered particularly for his naturalistic representations of the labouring classes, most of them done around his native village of Damvillers, near Verdun.

A fine draughtsman, he could also turn his hands to portraits of the great and the good. He was a patriot who fought and was wounded in the futile French war of 1870 against the Prussians.

His funeral was a magnificent affair for such a young man, not only attended by a large crowd including many other artists, but also graced with a war hero's military guard and the presence of numerous civilian and military dignitaries.

L'Annunciation aux bergers was his entry for the Prix de Rome at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in summer 1875. The 'Annunciation to the Shepherds' was the set topic for the contestants for the prize that year.

Bastien-Lepage's painting did not win, which caused much muttering among his supporters about the presumed establishment fix, but his defeat contributed to pushing him out of the stifling atmosphere of the Parisian art scene back to Dammvillers, where he created some of his greatest works. More detail about Bastien-Lepage's Prix de Rome setback is on the Google Arts and Culture page for the painting.

The contrast between the polished classicism of the representation of the angel (à la Ingres (1780-1867), according to Bastien-Lepage himself) and the precise realism of the painting of those shepherd nobodies is quite astonishing. Two worlds, the supernatural and the natural meet here, the one radiates its light into the other.

In the detailed realism of their representation – look closely! – Bastien-Lepage's deep veneration of the common people is there for all those with eyes to see. Christmas is, after all, the feast of humble origins.

Werner Bergengruen, The Shepherds (1958)

|

Die Hirten

Es roch so warm nach den Schafen, Da sind sie eingeschlafen. O Wunder was geschah: Es ist eine Helle gekommen, Ein Engel stand da. |

The Shepherds

It reeked so warmly of the sheep, there they fell asleep. What a miracle came to pass: a great light came and an angel was standing there. |

| Sie haben sein Wort vernommen, War schwer zu verstehen. Sie mußten nach Bethlehem gehen Und sehen. |

They heard his words, they were hard to understand. They had to go to Bethlehem and see. |

| Sie haben vor der Krippen Aus runden Augen geschaut. Sie stießen sich stumm in die Rippen. Einer hat sich gekraut, Einer drückte sich gegen die Wand, Einer schneuzte sich in die Hand Und wischte sich über die Lippen. |

The stood in front of the crib and stared wide-eyed. They poked themselves silently in the ribs. One ran his fingers through his beard. One pressed himself back against the wall. One blew his nose in his hand and wiped his lips. |

| Aber Iwan Akimitsch, der vorne stand, Der den heimlichen Branntwein braut, Iwan Akimitsch vom Wiesenrand, Iwan Akimitsch hat sich endlich getraut, Hat dreimal gespuckt, Dreimal geschluckt, Dann sagte er laut: |

But Ivan Akimitsch, who was standing at the front, who secretly distilled schnaps, Ivan Akimitsch from the meadow's edge, Ivan Akimitsch finally plucked up courage, spat three times, swallowed three times, then he said loudly: |

| 'Wir haben nicht immer gut getan. Du liebes Kind, Schau uns nur einmal freundlich an. Geh, tu's geschwind.' |

'We haven't always done good. You, dear child, just look at us kindly. Go on, do it, just quickly.' |

| Da war ihnen leicht, sie wußten nicht wie, Da fielen sie alle in die Knie, Da lachte das Kind und segnete sie. Joseph lächelte und Marie. |

It was easy for them, they didn't know why, they all kneeled, the child laughed and blessed them. Joseph smiled and Mary. |

Werner Bergengruen, 'Die Hirten', from 'Die verborgene Frucht' in Figur und Schatten, Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung / Die Arche, Zürich, 1958, p. 132.

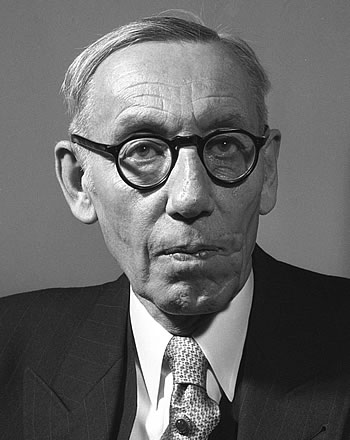

Doing justice to the biography of Werner Bergengruen (1892-1964) [pron. Bergengrün] would require at least another twenty minutes of scrolling from the reader, who at the end of that would still feel cheated.

He was a Baltic-German-Swedish-Latvian mongrel from a well-heeled family. He served in the German Army throughout the First World War and took up arms to defend Latvia from the Soviets in the years immediately after that. He started writing journalism in the 1920s, going on to build a literary career that brought him great acclaim.

The Germans of his generation all had to face that ultimate question: 'What did you do under National Socialism, Daddy?'. Many writers cooperated, some enthusiastically; many fled; some were reckless opponents of the regime and quickly became dead opponents; some, like Bergengruen, chose what came to be called the 'inner emigration': they did what they had to in order to stay alive, wrote what they could with their meaning hidden between the lines.

Fortunately for him, by the time the war broke out Bergengruen had become a popular and successful writer – even the Nazis would not openly move against him unless they had to. Nevertheless, there were numerous bans and restrictions placed upon him, but he survived.

Werner Bergengruen, 10 February 1954. Image: ©Unterberg, Rolf, B 145 Bild-00015397.

Brought up a Protestant, he and his wife converted to Catholicism in 1936 – another black mark against him from his masters.

After the end of the war, Bergengruen's inner emigration became an outer emigration: he lived ten years in Switzerland, then two years in Rome, then returned to Germany, where he spent the last six years of his life in Baden-Baden.

In 1953 he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature (it went to Winston Churchill that year).

Most people reading this – certainly those unfamiliar with German literature – may be wondering why they have never heard of Bergengruen. Apart from his publishers and estate defending his copyright to the extreme, his conservative politics and ideology were quite out of tune with the postwar political course taken by Germany. Death spared him most of the new age that began in the sixties.

The poem here is Bergengruen in a nutshell: his clever prosody, his religious sincerity and his humorous and Christian solidarity with the Lumpenproletariat, the great unwashed – much like that of Bastien-Lepage.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!