Bertolt Brecht's Erinnerung an die Marie A.

Richard Law, UTC 2021-10-07 07:11

An old friend recently introduced me to a masterly rendition of Bertolt Brecht's sung poem Erinnerung an die Marie A. My friend is a specialist in locating my many Bildungslücken, my cultural deficits, and Brecht's song was another tick on a long list of my oversights.

Readers of this website may recall that I am not a Brecht fan by any means and will understand that I generally prefer to keep my distance from the overrated genius.

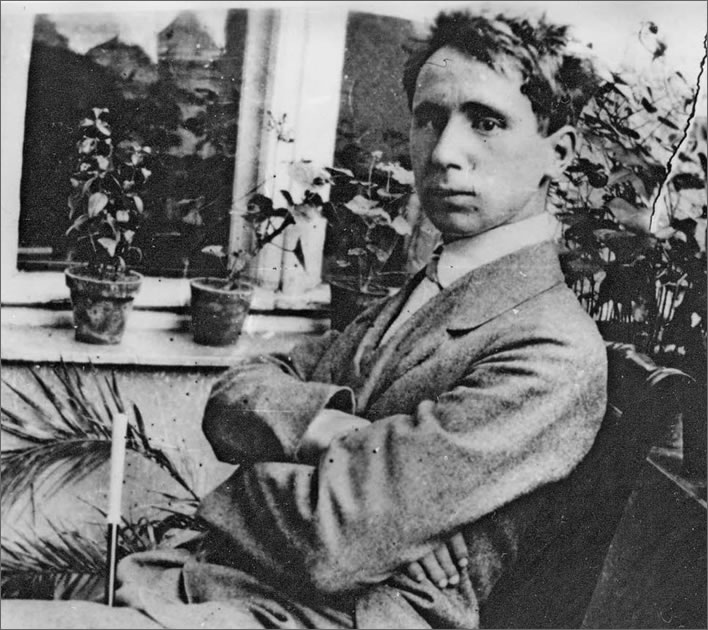

A photgraph of Brecht on the balcony of his family's house in Augsburg, taken around 1917, when he would have been around nineteen.

Brecht (1898-1956) wrote the poem in February 1920, famously during a long train journey from Augsburg to Berlin.

The poem was always intended to be a song. For its tune Brecht appropriated a melody from an existing song, Verlor'nes Glück, 'Lost Happiness' (1896), by the Viennese composer Leopold Sprowacker (1853-1936). Sprowacker's sentimental piece was in turn an adaptation into German of a popular, equally sugary French chanson with music by Charles Malo (1835-1914), Tu ne m'aimais pas, 'You did not love me'. In sum, we have fallen among thieves.

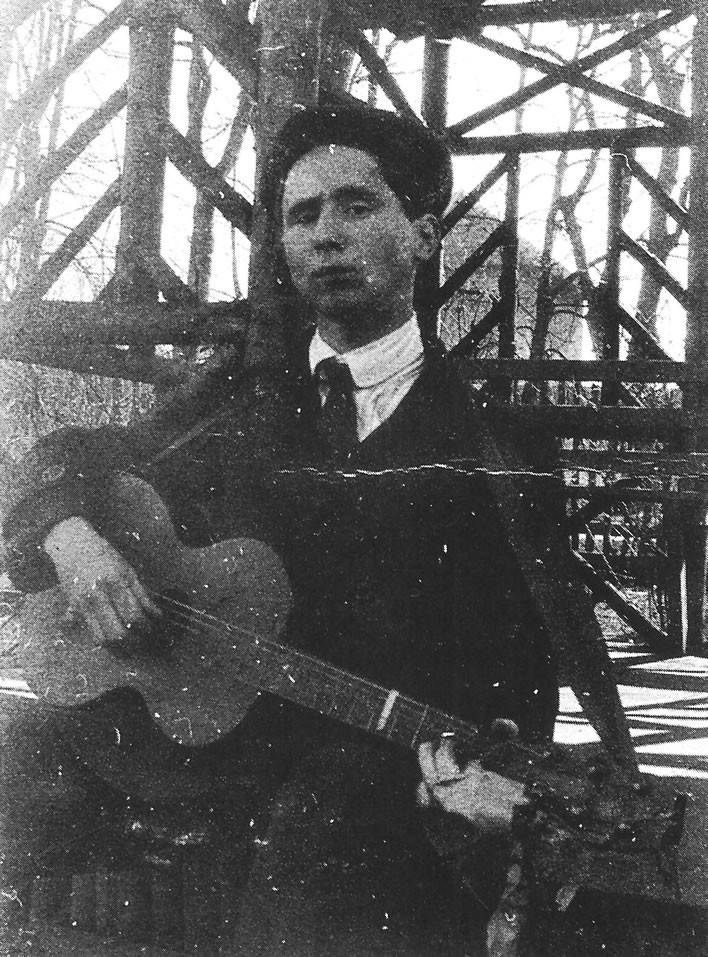

Brecht and guitar, presumably in the garden pavilion at his parents' house in Augsburg, taken around 1916. Image: Staats- und Stadtbibliothek Augsburg.

Brecht initially performed the piece to his own guitar accompaniment, but later his friend Franz Servatius Bruinier (1905-1928) created a rather rudimentary piano accompaniment for him. It seems reasonable to assume that Brecht had the melody of Verlor'nes Glück in his head while he was writing the text. The original chansons are now long forgotten, but Brecht's sung poem has many fans, even today.

Georg Schuchter [No date]

The audio is a recording of Georg Schuchter's performance of the song at the Wiener Metropol in 1998, accompanied by the Austrian pianist Bruno Juen.

It is a wonderfully intelligent performance, certainly the best I have ever heard.

Schuchter (1952-2001) was a popular Austrian actor, who died at the tragically early age of 48 in the pursuit of his passion, mountain climbing. He died on 29 September, so we have just missed the twentieth anniversary of his death.

If you listen attentively you will probably grasp the nuances in Schuchter's performance of 'Erinnerung' even if you have little or no German.

I have split the audio to correspond with the text stanzas in order to make following the text and music easier.

Let's look more closely at this text without invoking, for the moment, the hammer and anvil of literary scholarship. The German text is accompanied by one of our excruciatingly literal English translations. Almost everything we need for our understanding is there in the text, but, whilst the text is in front of us, I have added a few notes on particular points.

Erinnerung an die Marie A.

Bertolt Brecht (1920)

Memory of Marie A.

Erinnerung: By leaving off an article, definite (die) or indefinite (eine), Brecht causes his readers and his translator some head scratching. Is this meant in the sense of 'memory', 'reminiscence', 'recollection'? Or are we to take the poem as a 'memorial' to her? A native speaker of German would probably take 'eine' as implicit. In the context of the poem, 'memory' seems to be the most appropriate meaning. We might unleash the power of English and use a gerund here, 'Remembering Marie A.', but this is probably not what Brecht intended.

die Marie A.: Putting a definite article before a person's name is characteristic of vernacular German, particularly that spoken in southern Germany, Austria and Switzerland. The use of this form in the title alerts the reader immediately that the semantic register of the poem is colloquial German.

Stanza 1

An jenem Tag im blauen Mond September

1Still unter einem jungen Pflaumenbaum

Da hielt ich sie, die stille bleiche Liebe

3In meinem Arm wie einen holden Traum.

Und über uns im schönen Sommerhimmel

5War eine Wolke, die ich lange sah

Sie war sehr weiß und ungeheuer oben

7Und als ich aufsah, war sie nimmer da.

On that day in the blue month of September

silently under a young plum tree

I held her, the silent pale beloved

in my arm like a precious dream.

And above us in the beautiful summer sky

was a cloud, which I watched for a long time

it was very white and enormously high

And when I looked up, it was no longer there.

Notes

blauen Mond September: Mond is a poetic archaism ('dichterisch veraltet' the Duden notes) for 'month'. Brecht's striking use of blau, 'blue', for either the month or the meaning of moon that is implicit in Mond is superficially clever but just causes confusion – what is blue, the moon or the month or both? And why?

jungen Pflaumenbaum: Pflaume, 'plum', is a traditional symbol in German literature for [look away now, children!] the vulva. Here Bertolt has a whole tree-full of young ones to pluck. Bliss!

September…schönen Sommerhimmel: Having placed us firmly in September, Brecht describes the sky as a schöner Sommerhimmel. Although some sophistry over the exact end of summer and the beginning of autumn is possible, Central Europeans would probably not think of September as a summer month. The phrase schöner Sommerhimmel, however, lies ready to hand in the cliché toolbox, which might be the reason why Brecht chose it, despite its incongruity.

ungeheuer oben: Ungeheuer, 'monstrous', 'enormous' is a strange pairing for oben, leaving the reader unclear whether the cloud was very high up in the sky or very tall. In any case, it is a rather fearful expression to use in the circumstances.

als ich aufsah: The manuscript text of the poem in Brecht's notebook has als ich aufstand, 'when I stood up'. We'll discuss the reason for the change a little later, but aufsah causes the reader some problems of narrative flow. Brecht has just told us that he 'watched [it] for a long time' and now, with aufsah, he suddenly looks up. What has been going on in the meantime, the reader wonders.

nimmer: Purists may roll their eyes at nimmer used in the sense of nicht mehr, i.e. 'no more', when its canonical meaning is 'not ever', i.e. 'never'. It is, however, a common colloquialism, particularly in the dialects of southern German speakers (Brecht was born and raised in Bavaria).

Stanza 2

Seit jenem Tag sind viele, viele Monde

9Geschwommen still hinunter und vorbei

Die Pflaumenbäume sind wohl abgehauen

11Und fragst du mich, was mit der Liebe sei?

So sag ich dir: Ich kann mich nicht erinnern.

13Und doch, gewiß, ich weiß schon, was du meinst

Doch ihr Gesicht, das weiß ich wirklich nimmer

15Ich weiß nur mehr: Ich küsste es dereinst.

Since that day many, many moons have

hazily and quietly set and passed away

The plumtrees have probably been chopped down

and [if] you ask me what happened to the beloved one?

So I say to you: I cannot remember.

And yet, certainly, I know really what you mean

But her face, I no longer remember that

I know only that I kissed it then.

Notes

viele, viele Monde: The poetic archaism and ambiguity of Mond as 'month' has now slipped decidedly into Mond as 'moon'. Poets writing in idiomatic German can allow themselves language such as the repetition of viele to mean 'very many', a usage characteristic of the Volkslyrik, 'folk poetry'.

Geschwommen still hinunter und vorbei: We have to give Brecht credit for this beautiful line.

wohl: The word expresses a probability that the plum trees (now in the plural, suggesting that the tryst took place in an orchard) have been chopped down. The reader is puzzled that the 'young plum tree' of stanza 1 should have now been chopped down – but the tryst in the orchard must have taken place a long time ago, 'many, many moons' ago, in fact.

abgehauen: 'Hacked down' as a brutal process, not the neutral gefällt.

mit der Liebe: Brecht's creative ambiguity makes things tricky for the reader and the translator. Die Liebe in the first stanza was unambiguously 'the beloved', the person herself. Here it could be her, but just as well could be 'love' as the emotion, or even as an abstraction, or even the Act of Darkness itself, the Beast with two Backs, no less.

ich weiß schon, was du meinst: The sly 'I know really what you mean' could be taken as implying that the questioner is asking about the physical aspect of 'love'. Or perhaps not. Who knows?

das weiß ich: used in the sense of in Erinnerung haben or sich erinnern an, 'remember, recall' etc. An idiomatic usage with nothing to recommend it. Brecht seems to be playing with variants of wissen, 'know': gewiß, ich weiß schon, das weiß ich and finally ich weiß nur mehr. It all makes perfect sense as long as the reader does not ask what it means.

nimmer: Used in the same sense as in stanza 1.

nur mehr: Another idiomatic construction, the colloquialism for 'only that'.

Stanza 3

Und auch den Kuss, ich hätt' ihn längst vergessen

17Wenn nicht die Wolke da gewesen wär

Die weiß ich noch und werd ich immer wissen

19Sie war sehr weiß und kam von oben her.

Die Pflaumenbäume blühn vielleicht noch immer

21Und jene Frau hat jetzt vielleicht das siebte Kind

Doch jene Wolke blühte nur Minuten

23Und als ich aufsah, schwand sie schon im Wind.

And the kiss, too, I would have forgotten long ago

if the cloud had not been there

I can still recall it and will always be able to

it was very white and came down from above.

The plumtrees perhaps flower still

and that woman has perhaps just had her seventh child

But that cloud flowered only for minutes

and when I looked up it had already disappeared in the wind.

Notes

Die weiß ich noch und werd ich immer wissen: More wissen in the extremely idiomatic sense discussed in stanza 2. Note that the subject of the first weiß is die, which in the context can only mean die Wolke. Immer wissen clearly carries the meaning 'remember for ever'.

blühn vielleicht noch immer: The plumtrees that had wohl, probably, been hacked down in stanza 2 are now vielleicht, 'perhaps', still flourishing.

This statement presents readers with a narrative contradiction that is difficult to reconcile: we wonder why, after telling us in stanza 2 that the plum trees had 'probably' been chopped down, Brecht now suggests they may 'possibly' still be alive and still 'flower', in itself a further jarring contradiction with the autumnal setting of the seduction. We can imagine that Brecht, wanting to emphasise the ephemeral nature of his encounter with Marie, has now decided to extend the life of the plum trees in order to contrast their permanence with passion's transitory nature.

jene Frau: 'that woman', a dismissive, misogynistic phrase that a certain Bill Clinton was to make his own in 1998. The use of the phrase is characteristic of him and characteristic of Brecht.

blühte nur Minuten: Once again, we pedants are troubled by the short life of the cloud in this stanza compared with the long observation period: die ich lange sah in stanza 1.

schwand sie schon im Wind: More inconsistencies with this troublesome cloud. When in stanza 1 the speaker looked up, als ich aufsah, the cloud was nimmer da, no longer there. In a colloquialism in stanza 3 the cloud schwand sie schon im Wind 'it disappeared [already] in the wind' when he looked up: als ich aufsah. Imperfect the tense, imperfect the text.

Text analysis

Punctuation

On the evidence of this poem alone, we can state that Bertolt Brecht was a sloppy poet.

The most obvious aspect of that sloppiness is the punctuation – or rather, the lack of it. In the entire poem there are six full stops and one question mark. Two full stops in each stanza create two sections. Apart from the full stops and the question mark, there is no endstopping of the lines. Brecht seems to take a line ending as sufficient punctuation in itself – there is only one enjambment to break this rule: viele Monde / Geschwommen still [ll. 9-10]. A few commas appear within the lines, but on several occasions the second comma required to close a clause is missing, e.g. Da hielt ich sie, die stille bleiche Liebe[,] In meinem Arm. A comma after stille here would be nice, too.

Your translator began by punctuating the English text correctly, but, in the face of an unseemly crowd of [.]s and [,]s, soon gave that up as a bad job. The state of punctuation in the English translation reflects the state of punctuation in the original German: chaos, in other words.

For the reader, punctuation matters – unless, of course, the poet is after wilful obscurity. Brecht's defective punctuation is so bad that it is difficult to believe it is artifice in the pursuit of obscurity. Either he is spurning convention, because that was after all his USP, or he is just sloppy, perhaps thinking that his vernacular poem can do without punctuation marks.

Brecht initially called his poem a Lied and he performed it himself in public to his own guitar accompaniment on several occasions. If we strain very, very hard to be kind to him, we might note that his understanding of the poem may have been as a sung text, aurally received, not as the sort of printed text over which critical pedants crawl. He should at least have cleaned it up a bit for the print edition.

Irony

A characteristic of irony is that a text that is ironic initially misleads the reader, since its surface says something that is really the opposite of the deeper, genuine meaning. Sooner or later – sooner in the case of the alert fans of irony, later or even never in the case of the insensitive – the reader becomes aware of the deception and the clever trickery can be enjoyed for itself.

In this poem the title is the first deceit, since it speaks of the Erinnerung an die Marie, 'memory of Marie', when what we really get from the poem is Die Nicht-Erinnerung an Marie, 'no memory of Marie'.

Such misdirection is not irony, however, for there is no alternative reading – it is just deceit or, more accurately, sarcasm, which was one of Brecht's specialities in his writing and in his utterances.

Stanza 1: the chocolate-box lid

Some readers would claim that the first stanza is the ironic core of the poem. It is unabashedly 'romantic', 'sentimental', 'bucolic', even kitschig. The music Brecht and Bruinier adapted for the poem matches exactly the elegiac tone of that first verse. Schuchter's performance correctly takes this stanza at its sentimental face value and sings it accordingly.

Once again, we spoilsport pedants have to point out that this is not irony, but simple misdirection. No one listening to a performance of stanza 1 would have any reason to suspect the feelings communicated were not Brecht's own. Stanzas 2 and 3 are then just contradictions which puzzle and irritate the alert listener.

The first stanza was read aloud, not sung, in the much praised German film Das Leben der Anderen (2006) by an East German Stasi captain whose fascinatingly tedious job was listening in to the bugs placed in the apartment of a writer under observation. In the film, only stanza 1 of the poem – Brecht's 'chocolate-box lid' – is read out with a straight face, great emotion and complete elegiac conviction. How Brecht would have laughed! What purpose the scene serves in the plot is a mystery, but then narrative coherence has never been a feature of German drama.

Stanza 2: the great forgetting

The second stanza repudiates the mood of the first stanza totally.

The attentive listener or reader begins to puzzle: if Brecht's memory is now such a blank, where did the recollection of the 'silent pale beloved in my arm like a beautiful dream' come from. In the second and third stanzas we are told that the memory of the cloud is all that remains from the tryst in the orchard. If that is so, stanza 1 requires that all its images – the plum trees, the schöner Sommerhimmel etc. – all of these have remained in the memory. At best, the poet remembered all the externalities, just forgot about the girl a.k.a 'that woman'.

The accusation of inconsistency probably sounds pedantic and picky, but poems need to present coherent worlds to their readers.

The reader now also becomes aware of the deception inherent in the title of the poem that we have already mentioned: this poem is no Erinnerung, in whatever sense we care to take it, but really a forgetting.

Schuchter's performance of stanza 2 is exemplary. Despite all this confusion and all these contradictions in the text, he succeeds in reflecting the abrupt change from sentimental kitsch to brutal reality, in that he changes from song to narration – recitative, if you will – allowing him to handle, for example, the hard-nosed abgehauen, 'hacked down' with a fitting and beautifully judged, hard-nosed cadence. Most of the second part of the stanza is more narrated than sung, as it has to be.

Stanza 3: the cloud

The cloud is introduced in the second half of stanza 1. We were told there of its remarkable qualities, that is was very white and 'enormously high'. Brecht watched it 'for a long time', then (presumably) turned to his unfinished business with the pale girl. When he had finished and looked again, the cloud had disappeared.

The cloud is not mentioned in stanza 2, which concentrates on the evanescence of the girl. She seems to have disappeared almost as quickly as the cloud did. Once the show was over, our poet moved on. Well, that's Bertolt Brecht for you.

The cloud returns in stanza 3, taking up most of the stanza and asserting a dominant thematic role, for it is, according to Brecht, the only thing that he does now remember – apart from the kiss (a definite euphemism), which he also only remembers because of its association with the memorable cloud.

It's all rather too strange for the quizzical reader or listener to grasp easily. It is a bit of a surprise when we are told in this stanza that the plumtrees may well still be there in the orchard, flowering (unseasonably), and 'that woman' may still be flowering, as it were, with yet one more child for her large brood.

Schuchter copes well with Brecht's twists and turns in this stanza. In line 19 he switches away from song to narrative once more and continues in this manner until line 23, when he sings full throated Brecht's encomium for this remarkable cloud. Switching to narrative allows him to detach from the kitschig accompaniment and give the text the intonation it requires. All in all a sensitive and intelligent reading of a difficult, self-contradictory poem, which nevertheless manages to bring the best out of it – which is what good actors are supposed to do, after all.

Peeling back the title

Our textual study has dismembered most of this messy poem but we are still not in a position to say with any confidence what this poem is really about. The distances between 'oblique', 'obscure' and 'incomprehensible' are short.

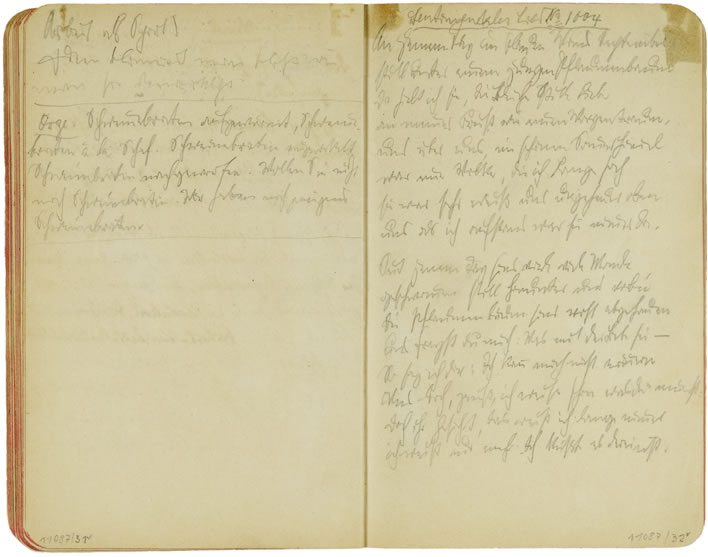

Staying close to our text and shunning circumstantial noise, we can make some progress in understanding if we look at the original manuscript text of the poem as it is found in one of Brecht's notebooks. There are few changes – the manuscript poem is almost identical to the text of the first printed edition, but the few differences there are are quite illuminating.

Where the printed version now bears the title Erinnerung an die Marie A. the original manuscript version was titled Sentimentales Lied Nr. 1004, 'Sentimental Song No. 1004'.

At which news the reader probably feels that this is a not really a great step forward in understanding.

On the contrary, it is a giant leap. The number 1004 is an allusion to an incident in Act 1, Scene 2 of Mozart and Da Ponte's opera Don Giovanni (1787).

At this point in the opera, Donna Elvira, having just been seduced and discarded by Don Giovanni in short order, is now confronting him angrily about his betrayal. Don Giovanni hands over his side of the conversation to his faithful manservant Leporello, who, in turn, attempts to calm the raging Donna Elvira by showing her the summary catalogue he keeps of all Don Giovanni's conquests throughout Europe. Just as she has been treated, all these women of all stations were ravished and then abandoned – it's normal:

Don Giovanni, Act 1, Scene 2, No 4 Aria, Leporello

| Madamina, il catalogo è questo delle belle che amò il padron mio; un catalogo egli è che ho fatt'io, osservate, leggete con me. |

My dear lady, this is a catalogue of the beauties my master has loved, a catalogue which I have compiled. Look, read along with me. |

| In Italia seicento e quaranta, in Lamagna duecento e trentuna, cento in Francia, in Turchia novantuna, ma in Ispagna son già mille e tre. […] |

In Italy, six hundred and forty; in Germany, two hundred and thirty-one; a hundred in France; in Turkey ninety-one, but in Spain it is now one thousand and three. |

The attentive reader will note that Brecht's Sentimentales Lied Nr. 1004 picks up exactly where Don Giovanni got to in Spain. Since at the conclusion of the opera Don Giovanni is dragged off to Hell, 1003 will always be his maximum score (in Spain).

It is also telling that, according to the editors of this notebook, the initial title was simply Sentimentales Lied. The handwriting shows that Nr. 1004 was added at a later time, even the underscoring of the original title was extended to match. How much later we do not know.

These facts strengthen our presumption that we made at the beginning of the present article that Brecht had the music of the original chanson in his head when he composed his text – hence: Sentimentales Lied. In which case it is also reasonable to assume from the sarcastic tone of the title that Brecht's song would certainly parody the original.

Text changes

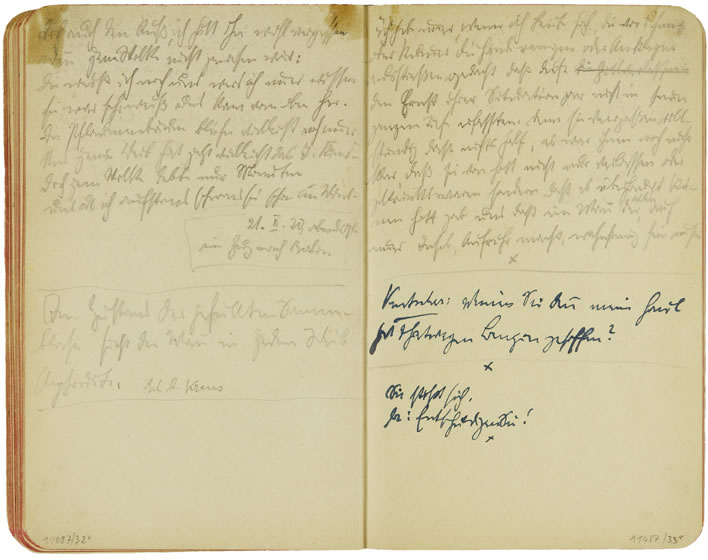

Apart from the title, there were two other changes to the manuscript text.

Firstly, where we now read 'In meinem Arm wie einen holden Traum' Brecht originally wrote 'An meiner Brust wie einen Morgentraum', 'on my breast like a morning dream'. It appears that this sentiment was too chocolate-boxy for Brecht, although vulgar minds may find it suggestively amusing.

Secondly, 'als ich aufsah' in the final version was originally 'als ich aufstand', 'when I stood up'.

All these changes, including the radical change of title, suggest an attempt to fudge the more obvious sexual allusions in the poem.

Here are the relevant notebook pages:

Bertolt Brecht, Notizbuch 3 (Januar bis April 1920) 31v-32r Image: Bertolt Brecht Notizbücher, Electronic Edition, ©2021 Suhrkamp Verlag.

Bertolt Brecht, Notizbuch 3 (Januar bis April 1920) 32v-33r Image: Bertolt Brecht Notizbücher, Electronic Edition, ©2021 Suhrkamp Verlag.

I can't show you higher resolution images of these pages. We should be grateful that the images of the pages and the texts of extensive commentaries have all been made accessible online, although this has clearly been done grudgingly to give some protection to the copright holders and their 14 volume print edition, which is still work in progress.

So if you want better, you will have to buy the book (49,95 €) or cut along to the Bertolt-Brecht-Archiv in the Archiv der Akademie der Künste in the Chausseestraße 125 in Berlin where, for legal reasons, the work can only be viewed in situ.

Facsimiles may also be found in various works on Brecht, such as Werner Hecht's Brecht, Sein Leben in Bildern und Texten [Frankfurt am Main 1988], in which a reproduction of the manuscript is to be seen on page 39.

We enjoy the seeming paradox that access to the works of the lifelong Communist and fan of East Germany Bertolt Brecht should be so restricted and only completely available when money changes hands. 'Twas ever thus, comrade, 'twas ever thus.

Augsburg to Berlin by train

An entry in the notebook dates the writing of the poem precisely: 21.ii.20, abends 7h im Zug nach Berlin. The entry is enclosed in a rectangular frame in pencil.

We pedants are a distrustful lot, particularly when it comes to the assertions made by creative artists, who are all, by definition, professional fantasists. The kindest thing we can say about the text of this poem as we find it in Brecht's notebook is that it must be a fair copy, it is so cleanly written – no crossings out, no erasures, no overwriting, no second or third thoughts. The flow of the handwriting suggests that the lines were written one after the other in prompt succession.

The fact that we find no trace of correction or rewriting might go some way to account for the many defects in this sloppily written poem.

Perhaps the drafts and scribbles of the work in progress were made on some other scraps before the poem was finally transferred to the notebook as a fair copy. But on a train?

Perhaps. The Berlin train left Munich at 7:30 in the morning. His friend Caspar Neher boarded the train in Munich in order to secure a seat for Brecht, who got on at Augsburg and took over Neher's seat. We are told the train was a 'D-Zug' type, a Durchgangswagenzug, so-called because a corridor (Durchgang) ran through each carriage along the length of the train. By 1920 the D-Zug had long become the standard wagon type for long-distance travel with only a minimum number of stops and the term came to be used for such trains (in the English sense of 'through trains').

Brecht's journey took place in February 1920, a few months before the first steps in the creation of the Deutsche Reichsbahn. Germany at the time was still attempting to rise from the wreckage of the First World War. Though not comparable with the destruction at the end of the Second World War, Germany's industrial base and much of its infrastructure was in disarray (as the French intended). Nevertheless, there were old-fashioned railway services of sorts, even though they were still primitive in modern terms. In February, when Brecht was travelling, the line between Munich and Berlin hobbled across the territories of several rail companies. During the journey, locomotives were changed, drivers replaced. Only after the formation of the Deutsche Reichsbahn was the network unified.

The rolling stock for lower class travellers was decrepit, the carriages were full and the journey, with many stops, could take anything up to twenty hours. Perhaps the German term Reiseproviant, 'travel provisions', still reminds us of a necessity for rail travellers at this time. The trains were crowded because there was no alternative.

On such a journey Brecht would have had plenty of time to put together his Sentimentales Lied and there were also plenty of stops during which he could have written down the poem. Brecht's own statement that it was written or completed 'at seven o'clock in the evening' would indicate he still had several hours to go before arriving in Berlin. Who knows?

It's worth mentioning that the German doctor/poet Gottfried Benn (1886-1956), an incomparably better poet than Brecht, wrote a poem in 1912 entitled D-Zug, which, much like Brecht's Sentimentales Lied, seems to have triggered erotic fantasies in its author's profoundly gloomy mind. There must be something about long-distance German rail travel that does this to you.

Priapus about to pop

Following the poem in the notebook is an entry that is characteristic of the priapic Brecht, one which has excited some critical notice: Im Zustand der gefüllten Samenblase sieht der Mann in jedem Weib Aphrodite, 'With his seminal vesicle[s] full, a man sees Aphrodite in every woman'.

The entry is separated from the poem with a line above it and it is concluded with another line below it. The handwriting is also noticeably different from that of the poem. It is clearly not associated directly with the poem, but rather just another entry in the notebook.

Brecht's sarcasm is on display once more in that he attributes the statement to Geh. R. = Geheimer Rat Kraus. The most famous Geheimrat, 'Privy Counsellor', was, of course Goethe, in his many years in the service of Karl August, Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach. For some reason, Brecht has given him the name 'Kraus', a name which seems to have no further meaning apart from being used sarcastically and childishly to insult the memory of the great Goethe, the anti-revolutionary pillar of the establishment.

The statement is a vulgar allusion to Goethe's Faust I, in the chapter the 'Witches' Kitchen', where Faust drinks the witches' brew. Faust wants Mephisto to conjure up for him the image of Helen of Troy, but Mephisto answers: Du siehst mit diesem Trank im Leibe / Bald Helenen in jedem Weibe, 'With this drink in your body you will soon see a Helen in every woman'. [Faust I, 'Hexenküche']

A photograph of Brecht in Augsburg, taken sometime around 1918.

Cherchez la femme

Had Brecht left the manuscript version of the poem unchanged in the print edition, a century of Brecht readers and critics would have had a better chance of working out what the poem was about: the misogynistic dumping of a used female. Who exactly the female, 'that woman', was is utterly irrelevant – we only need to recall that she was merely woman no. 1004 when the poem was written. After 'Marie A.' took over the title, readers of the poem now no longer have Leporello's help in working out its meaning nor Brecht's sarcastic title 'Sentimental Song' to set the mood.

But, with Don Giovanni gone, and a certain Marie A. in his place, the mention of a cryptic female name did what it always does: it set off one of those 'find the lady' hunts which give literary types something to talk about and which put food on the tables of the academic community.

There is no point taking you through the ins and outs of the search and the pros and cons of this or that girl called Marie. Knowing her identity – assuming for the moment that there was a Marie A. – would make no difference at all. The only thing the poem tells us about her is that she is/was bleich, 'very pale', which is actually more than it should, since Brecht claims not to remember her or her face at all.

An undated photograph of Brecht and Paula Banholzer, who got to know each other in spring 1917. His pet name for her was 'Bi', for 'Bittersweet'. His relationship with her lasted about six years.

An emotional and moral train wreck would be a fitting description for their relationship, which produced two illegitimate children (the second one probably aborted) and ran in parallel to Brecht's many Giovanni-like conquests of other women. Even after he had married someone else (Marianne Zoff), Brecht tried to lure 'Bi' – who by now was engaged to someone else – back into his orbit, seemingly to sabotage her impending marriage. By this time she had come to her senses and she rejected his advances. This unpalatable and sordid tale forms an important element of the biographical background to Erinnerung and die Marie A. but adds nothing to our interpretation.

Ultimately the poem remains what it always was, a badly constructed, sloppily executed, unimproved scribble during a train journey. Were it not for the interest of the musical setting (thank you, long-forgotten chansonnier!) we might have a hope that the poem would sink into deserved obscurity.

When my old friend mentioned the poem, he wrote of its 'mixture of sentimentality and male chauvinist casualness'. The wonder is that this poem and Brecht's work in general are still considered acceptable in German cultural circles. It should be no wonder: this poem, which is really an encomium to extreme misogyny (where is the #metoo swarm when you need it?), is worshipped and studied under the aegis of the left-leaning German intelligentsia from every tiny angle.

Scores of German schoolteachers, scribbling in their many free afternoons, during their long holidays and the endless days of lockdown have inflated the Wikipedia treatment of this ephemeral poem into a grotesque balloon which even gets the 'ausgezeichneter Artikel' accolade from Wikipedia. And let us not forget the smoky-voiced reading of stanza 1 in Das Leben der Anderen.

The current of communist thought – occasionally styling itself 'socialist' – has flowed deeply into German culture from its source in the middle of the nineteenth century down to the present day, as the results of the recent Federal Election in Germany make clear.

Brecht's technical incompetence thus goes unnoticed because his communist heart was in the right place – and that is all that matters in our post-post-modern era. Suhrkamp, his publisher, claims to sell 300,000 of his books every year. Given that currently there are about three million children between 15 and 17 years old in Germany it is really unsurprising that Brecht's presence on their obligatory reading lists generates that kind of demand from 10% of them.

The cloud revisited

The vision of the cloud occupies the entire second half of the first stanza. It is not mentioned in the second stanza, but the eight lines of the third stanza are all about the memory of this remarkable cloud. There can be no doubt that the vision of this cloud plays a very large role in the poem as a whole.

Ultimately, according to stanza 3, the cloud is the key thing that the poet remembers: anything else he remembers, he only remembers because of the cloud. In other words, the memory of it is the thing that has outlasted all else, even his loved one. Yet paradoxically, the cloud is the most short-lived phenomenon in the poem, it 'flowered only for minutes'. The most impermanent thing is in fact the thing that becomes permanent in memory.

Brecht also wrote a poem around 1919/1920 with the title Ballade vom Tod des Anna Gewölkegesichts, 'Ballad of the Death of Anna Cloudface'. One might imagine – as many of the critical fraternity have done – the treatment of the woman and the cloud in this poem can tell us something about the woman and the cloud in Sentimentales Lied Nr. 1004.

But although the two poems both talk of clouds, the tone of them both is completely different: the Ballade is a poem of loss, regret, death and oblivion, the woman's face evaporates into the cloud (hence 'cloudface'); the Sentimentales Lied is a poem of detachment and distance, a shoulder shrug. There is nothing in one that we can use in the explication of the other.

Whether the cloud itself is a symbol or metaphor for some thing or idea – well, I have no idea. The poem gives us no data to reach a conclusion in this respect. Perhaps it is just a cloud, or perhaps a metaphor for Brecht's Giovanni-like drive to bed one more woman, which evaporates after the successful conquest, or a proxy for the state of his seminal vesicles, or perhaps it is an attempt to express something that John Betjeman would express much more clearly long after Brecht and his Marie A., whoever she was, had already disappeared in the wind:

Why is it that a sunlit second sticks?

What force collects all this and seeks to fix

This fourth March morning nineteen sixty-sixDeep in my head?

'By the Ninth Green, St. Enodoc', John Betjeman, High and Low, 1966.

Who knows?

Coda 1

All poets know in their hearts that few people will read their stuff, a few well-disposed editors of magazines may dutifully print the odd poem now and again and a very few members of the general public will buy their books, should they ever find a publisher foolish enough to print them.

In the 19th century the way for a poet to reach a popular audience, certainly in Germany, was to get a poem set to music and have it become part of the massive singing tradition among the population. The art of poetry was then and is still leveraged by music.

This has remained the case ever since. The lyrics of popular music have become the poetry of this age. Millions of people, if asked to recite a poem, would merely look blank ar barely get beyond the second line; the same millions would be happy to take the stage at a karaoke evening and belt out one 'poem' after another.

Schuchter's wonderful performance has demonstrated the way that music and a sensitive performance can lift a work out of the depths. Readers who have followed our discussions on Schubert's song settings will understand easily how third rate poets such as Franz Schober and Ludwig Rellstab were saved from utter and deserved oblivion by Schubert's settings of their works.

In fact, in the case of Brecht's Sentimentales Lied Nr. 1004, now further romanticised as Erinnerung and die Marie A., we could argue that the popularity of the song is largely due to the haunting, elegiac, romantic melody it acquired from its now forgotten donors, whose versions, in their time, were popular songs. However much satire Brecht brings to the theme, the haunting, stolen tune of loss and rejection (Verlor'nes Glück, Sprowacker, Tu ne m'aimais pas, Laroche/Malo) has kept Brecht's poem afloat down the years.

Coda 2

Readers who are sceptical of my praise for Georg Schuchter's interpretation of Erinnerung an die Marie A. may care to listen to some other versions. Here are two classics:

Kate Kühl, Erinnerung an die Marie A., no date.

Ernst Busch, Erinnerung an die Marie A., no date.

Finally, let us repeat Schuchter's performance in its entirety.

Georg Schuchter, Bruno Juen (piano). Erinnerung an die Marie A., performed at the Wiener Metropol in 1998.

Note in particular the beautifully conceived and executed 'take-off' at the very beginning of the song. Note also the way the voice leads the accompaniment at the opening of the second and third stanzas, a technique which also legitimates the subsequent switches from song into spoken narrative. Note, too, the clever pause before 'als ich aufsah'.

Schuchter came from a musically gifted family and studied song and piano before he changed over to acting. It shows.

Now do you see what I mean?

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!