Winston Churchill's Wit and Wisdom

Richard Law, UTC 2022-01-01 07:21

Some burn damp faggots, others may consume

The entire combustible world in one small room

As though dried straw, and if we turn about

The bare chimney is gone black out

Because the work had finished in that flare.

Soldier, scholar, horseman, he,

As 'twere all life's epitome.

What made us dream that he could comb grey hair?

W.B. Yeats, 'In Memory of Major Robert Gregory' in The Wild Swans at Coole (1919)

Robert Gregory, the subject of Yeats' monody, died young as a flying ace towards the end of the Great War.

The subject of Werner Vogt's new tour d'horizon, Winston Churchill, Witz und Weisheit (Weberverlag.ch), was also a polymath, a 'soldier, scholar, horseman', also one whose courage was often tainted with foolhardiness. Churchill did not burn damp faggots, either: he was energetic, productive, a writer, brave – even in his 'wilderness years', even in his 'black dog' depressions, his polymath flame still burned.

Gregory, a minor aristocrat, was 34 when he volunteered, with a wife and three children. It was a noble, though unforced error. His last roll of the dice came in 1918, in a biplane over Italy: the dice fell badly for him that time.

Throughout his long life Churchill rolled his dice, too. They did not always fall perfectly, but he died in his bed, ninety years old. Even fine cigars and fine alcohol, both in heroic quantities, failed to kill him prematurely. Churchill's polymath flame burned well into his old age. The flame may have finally gone out in 1965, but, unlike Gregory's 'bare chimney … gone black out', Churchill left us with a mountain of artefacts from a long, eventful and consequential life. As Werner Vogt puts it:

This unparalleled vita is also unparalleled in its dimensions and its impact. And somewhat intimidating, too. The official biography of Winston Churchill, published between 1966 and 2019, comprises eight volumes of biography and 23 volumes of source materials, each of 1,000 pages or more.

Diese einzigartige Vita ist in ihrer Dimension und Ausprägung einzigartig. Und etwas einschüchternd ist sie auch. Die offizielle Biografie von Winston Churchill, zwischen 1966 und 2019 publiziert, umfasst acht Textbände und 23 Dokumentenbände von je 1000 und mehr Seiten. [p 14]

Add to that pile Churchill's own literary output and the secondary sources relating to each of the many and various interests of the polymath and we can see that the newcomer who wants to get to know something about Churchill stands at the foot of a great mountain.

Churchill specialists heave their way grunting and groaning up the slippery rock of this mountain. There are plenty of biographies of Churchill, offering the fixed lines and via ferrata which can take the curious reader up these exhausting slopes, but they are often themselves small mountains requiring some effort: the excellent 2018 biography by Andrew Roberts, Churchill: Walking with Destiny, will take you elegantly from the scree to the summit, but will require you to turn around 1,100 pages to get there. It's an enjoyable enough stroll, but a long one.

However, each generation has to confront the life and legacy of this polymath giant of history anew. This is particularly true for those who are not native speakers of English – in the present case German speakers.

Many will consult the Wikipedia entry for Churchill and be repelled by its typically narcoleptic, dry-bone density and humourless drudgery. It is fair to say that anyone who trudges through those ashes will exit knowing everything and knowing nothing about the great man.

Roberts' 1,000 magisterial pages are not for everyone, a wrist-wrecker on a bus journey, in no sense a 'carrying book' (©Russell Hoban). If you would see Churchill the man, the witty polymath, without wrecking your wrists or your eyesight, then Werner Vogt's 150 page book is for you.

At the end of those 150 pages, thanks to Vogt's light touch and humorous urbanity, you will know a great deal about Churchill the man. A complex man: an account of his childhood and early years alone would be sufficient to mitigate any serious charge in a modern court of law.

The roots of Churchill's long life reach back to a time when 'character' was everything. Kipling's poem 'If—' (written when Churchill was 21) is almost a perfect template for Churchill's life: 'If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster / And treat those two impostors just the same'. The entire poem can be read with Churchill in mind – only the battles with depression are missing.

In our modern age, character counts for little if anything: It is a great irony that Britain currently has a Prime Minister who likes to affect a Churchillian manner but who has a character that Churchill would have viewed with contempt: lying, dissembling, unfocussed, disorderly, cheating, treacherous, preening, unserious. The real Churchill may have enjoyed the odd cavalry charge, bullets whistling past his ears, but he was at heart a serious person. Johnson may be a slick wordsmith, but Churchill meant every word he spoke or wrote.

The pygmies of our age hurl invective at Churchill and throw paint at his statues for his 'crimes'. Well, we all make mistakes, even the great ones who make great mistakes, but in Churchill's complex character we find nothing malignant: he was a fearsome rhetorician with the associated skills of satire, irony and mockery, all of which he used to great effect on his adversaries, but nowhere do we find malice.

He had edges: he could be abrupt or fall into rages, but what he demanded from others pales in comparison with what he demanded from himself. When it came to making decisions of great import for the future of the civilised world, Churchill was much more often right than not and most importantly, right when it most counted to be right.

He was not 'wafted by a favouring gale' to become the leader of the free world in its darkest hour. If that position was his destiny, as many have asserted, among them Churchill himself, it was attained only by battling against and overcoming the most relentless and demoralising adversity.

Werner Vogt's book does not hide Churchill's mistakes or his eccentricities, but treats them with urbane humour as being part of that greater figure 'Churchill', whose character, tempered in setbacks and disasters, dogged by bouts of depression, this book delineates so well.

If you wish to encounter Churchill as though the living man, then Vogt's book is the cablecar that will take you elegantly and effortlessly to that giant summit. The subject is approached not through a smooth narrative – this book is not Andrew Roberts lite – but by taking facets from the life and character of the great polymath: 'son, husband and father', 'the pen and the sword', 'Churchill the artist' and setting out the luminous details which define the man.

Nor is the book merely a rehashing of the commonplace: Vogt includes material from his own interviews with Churchill's niece Celia Sandys and his wartime secretary, Elizabeth Layton-Nel. The book is properly rounded off with a timeline, a list of principal sources and a concise bibliography. There is unfortunately no index, but in such a well-organized text, readers will find what they are looking for with little effort.

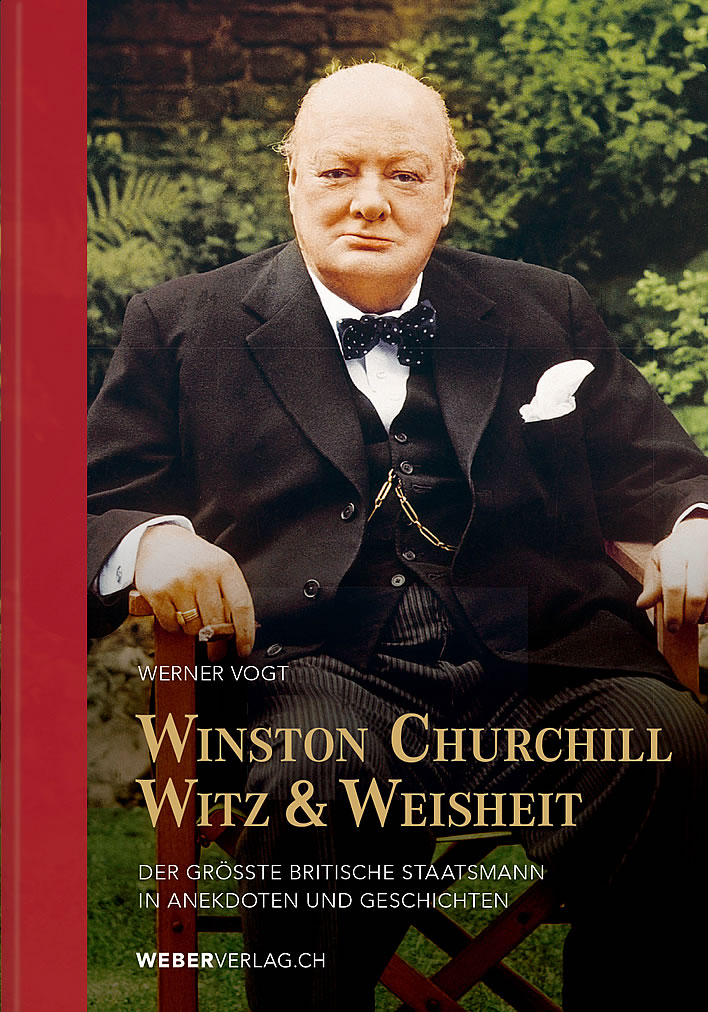

Physically, the book is beautifully produced. It has a handsome cover, fine paper and legible typography (a comfortable serif font with appropriately comfortable leading). The book is generously illustrated and the colourful caricatures by the artist Agnes Avagyan play an important role in setting the tone of the work and bringing a note of cheerful colour into the black and white artefacts of the Churchillian age. The book won't exactly fit in your pocket, but it won't break your wrist, either.

The modern who wishes to get to know the man who was unarguably the greatest statesman of the free world in the twentieth century can now with this book take a pleasant cablecar ride up that great mountain at the cost of an entertaining day's read.

Werner Vogt: Winston Churchill Witz und Weisheit, Weber Verlag AG, CH-3645 Thun/Gwatt, Switzerland. 160 Seiten, 16×23 cm, Leinen gebunden, ISBN 978-3-03922-140-0.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!