Immigration and the lost world

Richard Law, UTC 2024-02-23 14:50 Updated on UTC 2024-02-26

Immigration. Almost every problem that afflicts Broken Britain in 2024 is in some way linked to immigration. Government efforts over the last seventy years to pretend that this is not so and to keep a lid firmly on all dissent have brought the country to a collapse of free speech that is unique in recent history.

Time present and time past

You need to have the dubious blessings of old age and a long memory to recall a time when there was some degree of free speech in Britain. That time is gone now, so long gone that there are few left to remember it.

During the Second World War relatively mild action had been taken against malcontents and grumblers spreading defeatism among the people, but after the war the application of these restrictions faded away. The world had moved on.

After years of wartime fears and privations, people were happy to believe that a new and better world was coming. The deaths and losses of the war could not have been for nothing, could they? Rationing hung around somewhat longer than it should have done, the economic situation of postwar Britain was simply disastrous, but the dawn of the great Elizabethan Age was just around the corner. The two decades which followed the war were a golden age of free speech.

Free speech, acceptable speech

The term 'free speech' used here applies principally to political speech, taken broadly. All speech, even political speech, is subject to social conventions.

Like every well brought-up child I learned the limits of what was acceptable language in different situations: from the carefully sanitised tales I told my parents about my youthful doings to the need to speak in the register appropriate to the situation. Talking with my friends was one register; talking to the vicar or my headmaster was another.

The lost world. Richard's baby-boomer junior school class in the mid-1950s. Class size: 37! A lot of diversity there, too. Image: @FoS

These registers are moderated socially and not legally. Learning about them and respecting them are part of the process of socialisation. Using the wrong register in a particular context would not get you arrested – people would just think you had been badly brought up. If other people don't like what you say and how you say it, they are free to criticise you, ignore you, or dislike you. That's why today's ranting drunk on a budget airline or in an underground carriage is an issue of upbringing and decorum, not free speech.

Of course there were libel laws then and spreading falsehoods about people could be as expensive as it can now. It is also the case that the press at that time acted with a greater sense of decorum than it does today, although decorum can often mutate into the suppression of material that would actually be in the public interest.

The press in those long gone days had a monopoly on public discourse. Apart from the pub or the soapbox, there were no outlets for individual opinions – no blogs or social media. The press – all the news that's fit to print – was an arbiter of decorum. To a young person of today, transported back seventy years, this paucity of opinion would seem quite spooky.

But, in the street, in the shops, in the pubs, at your place of work, the citizen was free to say whatever he or she wanted within the bounds of good taste. A torrent of obscenities within earshot of a police officer might lead to a trivial public order offence, if a stern ticking-off on the spot didn't work.

Caution advised

The period around the 1950s was by any measure a golden age of free speech. However, in the history of Britain there have been many periods in which careless words had unpleasant and sometimes fatal consequences.

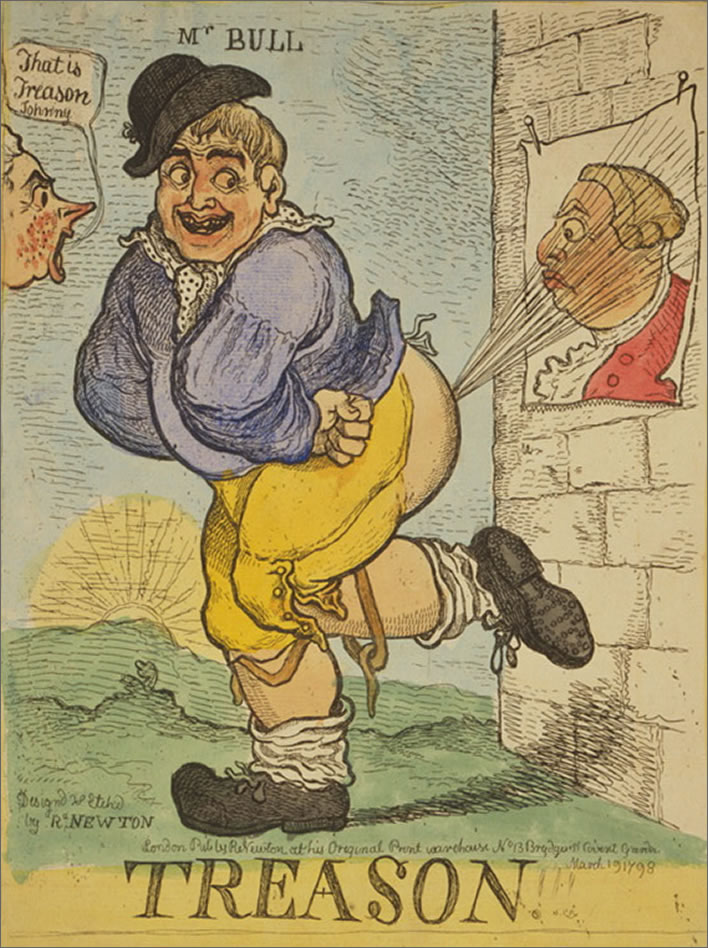

Richard Newton (1777-1798), 'Treason', 1798. John Bull farts at a caricature of King George III (1738-1820) pinned on the wall. The King shows surprise and William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806) exclaims: 'That is Treason Johnny'.

1798 was an annus horribilis in which almost everything the Pitt government touched went disastrously wrong. Unnerved by the French Revolution (1789-1799), like every other crowned head at the time, George and Pitt embarked on a period of warmongering and repression. Taxes were increased, armies were raised and habeas corpus was suspended. There were prosecutions for treason in 1794. George's carriage was stoned by enraged mobs at the opening of Parliament a year later. Unnerved by the revolting British populace, Parliament chose full-scale repression and passed the Treason and Seditious Meetings Acts and the Treason Act shortly afterwards. The second of these 'Two Acts' defined treason broadly as anything that might harm the King in any way at all – hence Pitt's designation of John Bull's farting as 'treason' in Newton's caricature. Newton died of typhus shortly after its completion. He was 21. Image: Library of Congress.

Richard Newton (1777-1798), an inspired caricaturist, died very young and thus escaped the persecution of the authorities. His publisher, William Holland (1757-1834), who owned a shop that sold prints, spent a year in prison for the crime of seditious libel – selling the Rights of Man (1791) a work by the notorious revolutionary, Thomas Paine (1737-1809).

There was repression, but it was a very British sort of repression, which flourished alongside the vitriolic satire of some the greatest caricaturists of all time.

There was widespread enthusiasm among many literary types for the French Revolution (1789-1799), at least in its first couple of years. The Bourbon monarchs had been an unlovely lot, foremost among them the odious Louis XIV, the 'Sun King', whose dissolute excesses were aped by the other great houses of Europe.

The French Revolution finally broke out under Louis XVI, but when it turned to bottomless barbarity, the enthusiasm faded and the fright spread rapidly. At the beginning of the Revolution, William Blake (1757-1827) had taken to walking around London wearing that Jacobin symbol, a Phrygian cap. As the barbarities mounted he wisely thought better of it.

The Continental way

British attempts to curb free speech look amateur when compared with the work of the autocratic despots of continental Europe, who envied and copied the French partiality to record-keeping and administration – the French gave the world the word 'bureaucracy', after all – and implemented it themselves according to their own lights. Despite or because of this repression in the service of tyranny, France got the bloody revolution it deserved.

Prussia led the field, of course, in the regulation of the citizenry. I have to chuckle whenever someone refers approvingly to Immanuel Kant's much cited but little understood essay 'What is Enlightenment?' [Beantwortung der Frage: Was Ist Aufklärung?, 1783]. The body of the essay tells us that we must throw off the shackles of conventional thought and 'dare to think for ourselves' – which is fine until we come to the conclusion of the essay, in which the great free-thinker decides that, by the way, we must show complete obedience to the glorious and wise ruler of Prussia, Frederick II. Disagreeing with the Prussian state would indeed be daring. After breaking free of the shackles of conventional thought the troublemaker would soon find himself in a set of conventional shackles in a Prussian dungeon.

The Hapsburg Empire centred on Austria, but was a conglomerate of many countries and languages that built up their own structures of oppression, accelerated by the fright of its rulers at the French Revolution. The lives of harmless composers such as Mozart (1756-1791) and Schubert (1797-1828) give us insights into the complicated apparatus of repression in the Empire: the narks, the secret police, the letter readers, the censors who had their fingers in every cultural corner, the prisons, dungeons and forced labour under conditions that effectively made them death sentences. Under the emperor Franz II/I (1768[1792]-1835), a weak-minded and fearful personality, the repression screw was turned ever tighter.

The Hapsburg oppression lasted throughout the nineteenth century. Its final manifestation is satirised in Czech writer Jaroslav Hašek's (1883-1923) subversive novel The Good Soldier Švejk, which opens with Breitschneider, the secret policeman, hanging around in a tavern and not only listening for any talk that could be taken to be seditious, but actually trying to lead those present into transgression.

The time was June 1914, just after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria. Needless to say, both Švejk and the innkeeper are arrested. The simpleton Švejk's harmless and idiotic riffs on the assassination bring down a long list of charges on his head, among them high treason.

Young people in most European countries probably imagine that the deeply ingrained habit of writing the name and address of the sender on the outside of a letter is merely a postal convenience for undeliverable letters. In fact, the habit is a leftover from centuries of censorship in Europe, it was a convenience not for the post but for the censors. Mozart had numerous ruses to anonymise his letters.

This habit of declaring the sender of a letter was unknown in Britain, of course, which fact suggests a key difference in the experience of free speech and censorship between Britain and continental Europe.

It was in London that Karl Marx (1818-1883), persecuted and exiled in Germany, France and Belgium, from 1849 was able to spend the last 34 years of his life in relative safety, scribbling in penury. Whilst Europe spent much of the nineteenth century scratching at the scabs left by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic adventure, Britain became a self-confident nation assured of its role in the world.

The bluebottles are back

By the 1950s we Britons had good reason to think that such secret police stuff was finally behind us, never to return.

…With what radiant hope

Men formed this many-branched electrolier,

…

They felt so sure on their electric trip

That Youth and Progress were in parnership.

John Betjeman, 'The Metropolitan Railway, Baker Street Station Buffet' in A Few Late Chrysanthemums (1954).

It didn't last long, perhaps two decades at the most. An almost imperceptible slide into censorship and authoritarianism brought us to where we are now, seventy years later.

And where is that? Britons now converse guardedly in the taverns of social media and curate their language, just as our forebears did, while the cops and their algorithms pay close attention and wait for someone to rat out the offenders – 'Bluebottles' the Viennese called the lurkers in taverns.

These days the ratting out process has been automated: most social media sites make the nark's task easy by offering a 'report this' button. Bots continuously search through text and images on the look out for something unsayable. When humans finally get involved, we have arrived once again at a point where the police are feeling the collars of substantial numbers of citizens simply because of something they said or wrote.

A particularly striking example was a recent case in London involving a black Christian preacher, singing in front of a shopping centre with the Potters House Church choir, who took as his text John 3:16: For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life. The preacher asserted that Jesus loved everyone, regardless of 'orientation', etc. and that those with faith in Him, whoever they were, could relax in the assurance that He would save them.

It was a remarkable oecumenical and inclusive message of love and hope on the basis of a major biblical passage.

Except that someone went to some cops on the street and told them that the preacher's words had hurt them. The police then dressed down the preacher in that humourless way that is today all too familiar and after much fatuous argument, informed the preacher that he was guilty of a 'hate crime' which had caused 'alarm or distress in a public space' and which would now be reported for further review. He was now required to supply his name and address. If he failed to do so, he would be arrested and taken off to the police station, where a night in the cells might concentrate the young family man's mind.

Such instances constitute the new normal of daily, low-level repression; they take place everyday and with each day they become ever more unexceptional – unless, that is, you are one of the few remaining people, grey and powerless, with long and intact memories.

If you say something unpleasant these days while under the influence of something or other, those words will get you into trouble. In the fifties, drunkenness and causing a nuisance might get you a night in the cells, perhaps a small fine and get you bound over to keep the peace. What you said when drunk was just 'the drink talking' and no one took it seriously. Nowadays, everything is taken seriously, just as a hundred years ago, everything that the certified idiot Švejk said was taken with utter and comic seriousness.

This is where we now are. It didn't last long, that golden age of free speech in the fifties. What happened to it? The event which ended it was the beginning of the immigration of people from outside the European cultural pool. This is my sermon for today, that without immigration, Britain would today be a much saner country with a tradition of freedom of speech that was still intact.

The long march to intellectual serfdom

We fifties Brits were broad church xenophobes. My parents said things about members of some of the sub-tribes of the Great British tribe, such as people from Lancashire, which would get them into hot water these days – such grumblings were then unexceptional, the sort of things that most of the people I knew also said. I am sure that those not blessed by God to be part of the Yorkshire tribe said unpleasant, envious things about us, too.

My parents may not have been fans of Lancastrians, but they were fans of the American singer Paul Robeson, an imposing figure, a fine bass-baritone, well-spoken, a Negro as he was called then (and called himself), who seemed to be both noble and on the side of the working man.

The word 'Negro', which nowadays no one dares to write or utter, was then a quite normal word without any trace of dislike or animosity. Its venom was inserted by one of the great modern roots of evil, the racial conflict in the USA arising from slavery.

I would expect a modern person, reading that word here, would have experienced a little frisson of shock that the word wasn't masked with asterisks or replaced by the childish expression, 'the N-word'. I'm not going to play that silly Orwellian game with my readers, where words we all know once existed have been erased by Newspeak – except they haven't. Examine your memories: they are all still there, without a single asterisk among them.

I may be imagining this, but I believe that in Britain in the fifties and for quite a while thereafter, the word 'black' as applied to a person was barely used, if ever. When 'black' did come into the language around the 1970s, I felt – and still feel – a disinclination to use a word I considered at best indelicate, at worst an insult. If 'Negro' was good enough for Paul Robeson and Martin Luther King, it's good enough for me.

In Britain, if my memory is correct, the criteria for fearing the stranger were not particularly race or origin. Unlike the USA, Britain did not have the festering legacy of slavery. In Britain there was one criterion: otherness. In the normal course of things, the individual stranger would over time become less other and at some point would be largely accepted into the tribe – even those 'others' from Lancashire.

We must note here the essential difference between xenophobia, the suspicion or fear of the stranger, and the racialist doctrine that discriminated against the American Negro in the US. Continued proximity and time could overcome the former; the latter was a blood libel, an imagined stain that could never be washed away. By the middle of the twentieth century, the American Negro had been in the country in growing numbers for more than two centuries – longer than many of the immigrants who came in the later waves – and arguably in this time nothing had changed.

New workers

But immigration brought not one or two strangers but substantial numbers of them. Substantial numbers every year – and every year more and more. Unrest expanded beyond simple xenophobia into completely legitimate worries about employment, wages, social security, health, education and whether the promised land of integration was even achievable.

Understandably, many immigrants, being themselves among strangers in a strange land, took comfort in their own company and distanced themselves from the 'others' around them. Within a short time colonies grew up which nurtured and reinforced their own otherness. You can have integration or you can have diversity. You can't have both. You can have social cohesion or diversity. You can't have both.

The Government did not expose its thinking behind its drive for immigration. That thinking is still cloudy today, even with the benefit of hindsight and historical records. The suggestions that immigration was part of some grand plan to bring more people into the tax system or rejuvenate the workforce are absurd. Increasing GDP by simply enlarging the workforce is clearly demented.

The fifties are characterised by the 'baby boom'. There was no shortage of children – just the opposite. Furthermore, I can think of no time in the last sixty years when Britain had a shortage of workers. In contrast, there were plenty of times when the country had a shortage of jobs and too many workers. From any rational viewpoint, Britain simply did not need immigrants.

With the exception of the Kenyan Asians, who had been booted out of their adopted country by the unlovely Idi Amin, there was no general flight from war and persecution. My recollection is that discussion about the justification for immigration never reached critical mass, never really became an issue.

If immigration was intended to aid struggling industries, it failed miserably. The textile mills of the north were indeed on their last legs. They could not survive growing international competition and technological progress. The newcomers' low wages gave the industry a stay of execution, but within a couple of decades the game was up for mass textile production in Britain.

Moving on

The mills emptied, the colonies of workers they had imported remained. The quick economic fix failed miserably, its consequences remained. Ironically, Pakistan, the country of origin of many immigrants into the textile trades of the north of England, became a world leader in textile production, whilst Britain's textile trade melted away like April snow.

In the fifties and sixties dockers were marching against the low-wage replacements in their declining industry. But just as with the textile mills, within a few decades much of the traditional dock work had been swept away by technological progress. And just as with the textile mills, the immigrant workers remained.

The simple term immigration masks all the subtleties of social change and deep-seated ethnic identity that are involved.

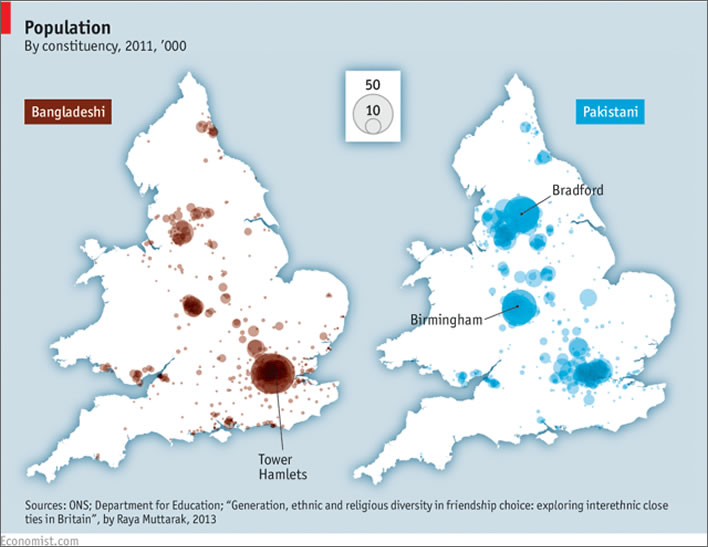

For example, it was mainly Pakistanis who found their way into the mills and factories around Birmingham and (greater) Bradford. About the same time, a wave of immigration of Bangladeshis began. [The province we oldies used to call Bengal, whose name was an essential component in a thousand vulgar schoolboy limericks, separated from Pakistan in 1971.] Some of them ended up in the Bradford and Birmingham area, like the Pakistanis, but the London Borough of Tower Hamlets became the epicentre of Bangladeshi settlement.

Pakistani and Bangladeshi in Britain. Two more layers on the ever more complicated electoral map. Image: ©Economist.com.

Remarkably, after the old employments fizzled out, each of the two communities developed its own employment preferences: the Pakistanis took up taxi driving, the Bangladeshis branched out into restaurants. [The Economist, 'Breaking out', 19.02.2015]

It is particularly interesting to note that these two different sources of immigrants have not just preserved their own communities by very limited integration with the indigenous British hosts, but preserved their own identities from integration with each other – in this case probably not surprising, given the struggle Bangladesh had to attain its independence from Pakistan. Whether people are indigenous or immigrants, the bonds of culture and community are immensely strong and propagate down the generations.

Why was this immigration necessary? What was this social reconstruction for? As any rational economist will tell you, attempting to save unprofitable businesses by importing unskilled workers into low-paid jobs is the last thrash of a drowning industry before it finally goes under – and so it was in these cases. As the example of the Pakistani and Bangladeshi immigrants shows, the best way is to let people work out their own economic salvation in a free market as Adam Smith (1723-1790) and Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) told us.

However, we free-market optimists are not blind to the fact that a few service activities such as taxi driving or running a cheap restaurant don't add up to a successful economy. The map of Pakistani and Bangladeshi immigrant colonies depicts areas substantially blighted by social and economic decay.

Seventy years of downward pressure on wages have created a society in which somewhat over half of wage-earners do not even earn enough to qualify for paying income tax. Let that sink in: too poor to pay income tax.

Immigrant citizens

European states inherited traditions of documenting and monitoring their peoples. Most had time-limited residence permits or work permits for foreigners. The step up into full citizenship was quite restricted.

Britain, in contrast, had a largely paperless tradition. No one needed to notify the authorities of their place of residence; for a long time driving licences were handed out without the need for a driving test; hardly anyone needed a passport. The only paperwork most people possessed related to their passage through life: certificates of birth, marriage and death. What happened in between was largely their business.

Compare that with post-war Germany, where every change of address involved the completion of a ten-part form, whose parts would be passed on to the local council, the tax authorities, the police, the social services etc. etc.

British low-key, non-intrusive administration was not geared up to the challenges of mass immigration. The first step for immigrants was not reporting a residence but the acquisition of British citizenship. The British mocked the bureaucratic need of foreign governments to demand that their citizens produce some form of ID on demand. But once a citizen, the immigrant is an immigrant no more.

This British generosity towards economic immigrants was remarkable and quite unique. On the Continent, Switzerland led the field in terms of the heartless bureaucratic rigour with which these regulations were imposed. The country has a long tradition of recruiting workers from the poorest areas of Italy and Spain for seasonal labour in the fields or road building and tunnelling. When the season ends or the project is completed, they are expected to go back to their countries of origin – Switzerland recruited labourers, not citizens.

A substantial number of foreign labourers never survived the dangers of alpine tunnelling, or did so only with terrible injuries. The bodies of the dead were rarely repatriated to their home villages, unless someone paid. It was a common occurrence that miners were sent back to the tunnel face without allowing enough time for the noxious gases and rock dust of blasting to clear properly. When they were not killed in rockfalls, sudden water run-ins or blasting accidents, many would return to their villages and families with lungs and health wrecked. Strikes over conditions and unrest were put down bloodily.

A shrine to Saint Barbara, patron saint of miners, blasters etc., erected by the mainly Italian workers who built this hydroelectric Wasserschloss in the Swiss Alps. Many such shrines are to be found associated with large and small construction projects in Switzerland. Passers-by leave trinkets, attractive stones, in autumn pine cones, in summer fresh meadow flowers. The shrine is still carefully tended to this day, more than thirty years after the project was completed. Image: ©FoS

Such workers never even got the chance to become immigrants. Even more settled workers were at continual risk: if you lost your job, you and your dependents lost the right of residence.

Keeping a lid on it

Whatever successive British Governments thought they were doing by allowing such substantial levels of immigration combined with a fast track to citizenship, they were forced to do something to silence public discontent and put a lid on the population's natural xenophobia. Discontent arose not only from xenophobia but also from the many practical problems that immigration created with its demands on scarce resources: welfare provision, housing, education, health and so on. The social stresses and strains which accompanied the acquisition of a tribe of taxi-drivers and a tribe of restaurateurs were arguably not worth the trouble.

Worst of all, mass immigration was a policy upon which no voter had ever had the opportunity to vote. It became the great unmentionable and those who objected to it were isolated and demonised.

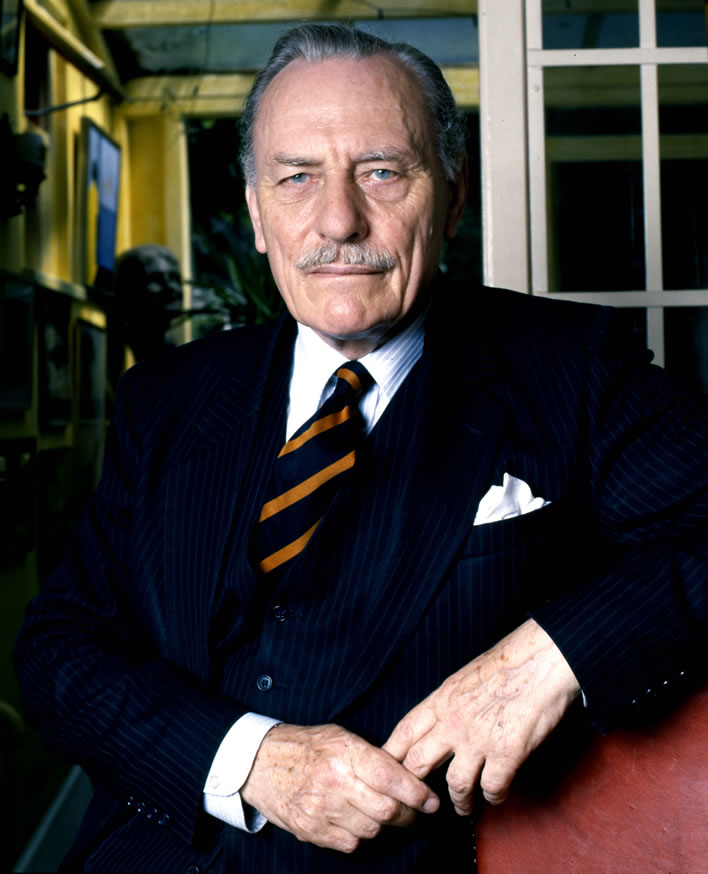

The much-maligned Enoch Powell was demonised for daring to warn against the consequences of mass immigration. During its early phase, the effects of immigration were not very visible. A simple lad from the north of England, I was twenty before I encountered my first non-white person face to face – and it was several more years before I encountered my second.

Enoch Powell (1912-1998), 1987. Image: Photographer Allan Warren.

At that time, most Britons were not confronted with the fact of immigration. For them, Powell's warnings could be easily dismissed as alarmism. But his warnings were not about the present state of the country, but rather the future state if immigration were not to be reduced. He was right – and the government knew this, because since then it has devoted much legislative and administrative effort to suppressing at any cost the 'rivers of blood' which he foresaw.

Although successive governments treated Powell badly, it is clear in hindsight that they too saw the spectre of his worst fears. That Powell's vision of the foaming Tiber has not materialised is only because of invasive legislation that has shackled modern life. The price of keeping that lid on discontent has been very high.

Once the legal measures to suppress public discontent with immigration were in place, the path had been cleared to allow an ever more invasive regulation of behaviour and speech.

Shaping the language

Over the last seventy years or so the English language itself has been reshaped in the interest of keeping a lid on discontent with immigration.

For a person born after 1980 or so, the terms 'racism', 'racist', 'hate speech' and 'hate crimes' are very definitely 'things'. These terms and their fellows are now thrown around in discourse with complete confidence in their 'thinginess'.

The recollections of those from previous generations may differ. A person born in the 1940s as I was can remember a time when none of these terms existed, at least in the common tongue of Britain – the particular nightmare of race that was endemic in the United States was generally considered to be their problem, not ours and we wasted no time thinking about it.

We made do with one term, 'racial prejudice', which described the situation accurately and truthfully: a prejudice being a preliminary opinion formed without knowledge. It is a hopeful term, not an insult, because a prejudice, in its nature, is something that can be overcome. It was also, certainly in the early days, barely used. As I noted earlier, all attempts at a rational discussion about immigration foundered in the morass of irrelevant racial terminology from the USA.

Since then, the accurate and meaningful term racial prejudice has faded away, elbowed out by 'racist' and 'racism'. My understanding of this point is confirmed by a glance at the dictionary definitions for 'racism' from around the mid-twentieth century.

You do not believe me that a long time ago we all managed without the words 'racist' and 'racism', now indispensable? Let's do a bit of lexicographical time travel.

Going back to 1946, the highly abridged Pocket Oxford Dictionary edition of that year, a handy dictionary that represents the core of the language for the everyday user, makes no mention at all of 'racist' or 'racialist'. We can confidently state that the two terms are not (yet) part of the common language. The word 'racial' can be found, but only as a neutral derivative of the word 'race'.

My two volume Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, in its main section (1947), has no entry for 'racism'. The Addenda (1973) has one entry which at that time was on its way to the full OED. The etymology sources 'racism' to 1936:

'The theory that distinctive human characteristics, abilities etc., are determined by race. also = *RACIALISM. Hence Racist a. and sb.'

The Oxford lexicographers display their usual precision: the equals sign and that little asterisk tell us that this equivalence is 'not actually found, but … the existence is inferred'. Thus we are sent to 'Racialism', the previous entry, a word that was first recorded in 1907, where we find:

Belief in the superiority of a particular race; antagonism between different races of men. Hence 'Racialist' a. and sb.

The executive summary here is that in 1973 the word racism existed, but only just: it had yet to get its entry in the full OED. It had certainly not reached general currency. Now it seems to pop up in every second sentence.

My memory, of course, can play tricks with me, but not on this occasion it seems. At least up to the mid-seventies of the last century, the word 'racism' did not exist in the common speech. That is yet another indicator of the great changes that immigration brought about in our daily lives.

Yet another loss to the language is the desuetude of that precise word 'immigration' itself. Things were so clear in the fifties: we had immigrants who arrived in Britain to settle and we had emigrants who went off to Australia or Canada. The words 'migrant' and 'migration' applied to birds such as swallows and wandering folk such as the Huns, Goths and Visigoths. Nowadays, all immigrants are migrants, driven by unfathomable social and ecological imperatives beyond their control. And whether immigration or migration, any challenge or questioning is now unquestionably 'racist'.

Levelling up

We should recall that the Race Relations Act 1965, ditto 1968 and ditto 1976 had reached the statute book during this period, but that the focus on the legislation was always on the prevention of discrimination on the grounds of race. The word 'race' here is actually a synonym for 'immigrant', since before the start of mass immigration Britain was an almost complete racial monotone. The only 'races' in Britain were immigrants. Please don't write me tracts about Britain the 'mongrel nation' – this canard is simply not true.

The sleight of hand that made a principled opposition to immigration a 'racist' phenomenon effectively put such discussions beyond the pale of polite conversation. Since that moment, any discussion of immigration is recategorised as a discussion about race.

Britons have become so used to these really remarkable pieces of legislation that they have forgotten how remarkable they were. In the interest of the welfare of the immigrant, following the pattern set in the USA, the government interfered in everyday affairs in many ways to stop discrimination against the immigrant in employment and many other areas of life.

In his famous 'Rivers of Blood' speech in 1968, Enoch Powell summed up concisely the novelty of the impositions on the private citizen which the various Race Relations Acts created;

The third element of the Conservative Party's policy is that all who are in this country as citizens should be equal before the law and that there shall be no discrimination or difference made between them by public authority. As Mr Heath has put it we will have no 'first-class citizens' and 'second-class citizens.' This does not mean that the immigrant and his descendent should be elevated into a privileged or special class or that the citizen should be denied his right to discriminate in the management of his own affairs between one fellow-citizen and another or that he should be subjected to imposition as to his reasons and motive for behaving in one lawful manner rather than another.

It is, of course, a terrible and hurtful experience for the immigrant to be ostracised from so many basic aspects of life and no humane person wants that. But we should reflect that the ostracism wouldn't occur if the immigrant weren't there. There is no right to immigration. This novel legal creativity would have been unnecessary without mass immigration. The difficulty arises solely from the presence of more and more strangers down the years.

But in the 1950s, Britain had no such problems. It had as good as no immigrants and no such remedies of legally mandated equivalence were necessary to force a reluctant populace to accept the newcomers. The remedies had to be found as a result of that great unnecessary, mass immigration.

Disaster with no return

The situation was made worse by the stupid decision to make immigrants from the colonies citizens in one, prompt bound. This was done by the British Nationality Act 1948, another disaster brought to Britain by the postwar Labour government, the government that also brought us the National Health Service and the deplorable pension system that has kept working-class pensioners in poverty ever since.

That act was the starting pistol for the waves of immigration that began then. Note that Heath spoke of 'first-class citizens' and 'second-class citizens', a problem that arose directly from the the immediate transition from immigrant to citizen.

In 1962, the then Conservative government attempted to restrict immigration with the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962. More restrictions were added by the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968 and some more in the Immigration Act of 1971. The last two measures were supported by both Conservative and Labour MPs, spooked by the scale of immigration that had been set in train after the war. Immigration is a ratchet: each click is irreversible.

Enoch Powell asserted not only the need to restrict immigration but also to roll back the number of immigrants already in the country by encouraging 're-emigration' – which meant, at that time, crossing the immigrants' palms with enough silver to encourage them to go somewhere else. It was never tried and it is doubtful it would have worked anyway.

It was certainly not the even-handed treatment of citizens that Powell demanded. The low-paid worker would have justifiably resented giving a sum that would probably have been a multiple of his annual wage for someone just to go away. Short of rounding people up and deporting them, which no sane or humane person wants to do, immigrants will remain as long as they want.

Legislative and administrative creep

In the UK, once the equal right of access for immigrants to employment, housing and all the apparatus of the modern state had been regulated, the tone changed. The interference by the government in the behaviour, the speech and even the putative thoughts of the citizenry, once established by precedent, spread out to the extent that we feel it today. Once the powers that be acquired a taste and an ability to regulate speech, there was no stopping them.

We started wanting to make immigrants feel welcome and to shield them from the harsh words of the natives. Nowadays we have 'hate' speech and 'hate' crimes and so many shades of utterance that are now classed as reprehensible. We have moved from the regulation of what a person thinks about immigrants to what a person thinks about almost anything of consequence. So much new legislation is concerned not with deeds but with opinions and attitudes. The habit of using the law to regulate interpersonal relationships has become ever stronger.

The repeated conflicts in the Middle East and the unrest in eastern Europe arising from the collapse of the Soviet Union led to the growth of immigration by people claiming asylum. On the face of it, asylum should be easier to control than economic immigration.

It is a well-established rule that asylum should be sought in the first safe country entered, in which case Britain, on the outside western edge of Europe, appears to have no obligation to give anyone asylum. The half-century Britain spent in the EU and its precursors trained Britain into doing its bit in taking a share of the asylum seekers/immigrants who turn up on its distant outer borders. Old habits die hard, we say, but in this case the habit is still with us despite Brexit. Delivering the boat loads of illegal aliens intercepted in the English Channel safely back to France from whence they clearly came is an option that is studiously never mentioned in polite conversation.

Full circle

Thus the arc of the last seventy years has brought us from a period of relative social harmony and an almost unrestricted ability to voice opinions to an age of the most intensive restrictions on speech.

Modern censorship has gone so far that it is difficult to distinguish it from some of the historical examples of repression already mentioned. Both then and now arrest, fines, imprisonment, confiscation and loss of employment awaited those who defied the government orthodoxy. Admittedly dungeons, thumbscrews, forced labour and executions are fortunately off the social control menu, but in return, the authorities have nowadays a much greater range of measures which they can use to identify the troublemakers and bring them to heel.

George III and the Pitt government in Britain and Metternich and his ilk in Europe would have been delighted to have the oppressive reach that modern governments have.

All these modern despotic measures have their roots in the government's need to keep the lid on public resentment of immigration. Without that, none of them would be needed.

Update 26-02-2024

The two paragraphs beginning here have been lightly rewritten to clear up some confusion in the original text. Thanks to reader DjC.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!