Two images for August

Richard Law, UTC 2025-08-02 09:03

Heinrich Pestalozzi

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827) is remembered as a Swiss educational reformer. He lived in a period when educational reform was one of the issues of the age. At the start of this period, education for the common people was as good as non-existent, apart from that offered by a few religious institutions. By the end of the period, enlightened rulers began to see an educated citizenry as an essential prerequisite for a successful state. Nowadays we take such things for granted.

Of all his achievements, one particular moment in Pestalozzi's life brought him a legendary status as a symbol of Christian charity and humanity in a wicked world. Among German historians this moment is known as Die Schreckenstage von Nidwalden, 'The Days of Terror in Nidwalden', which took place on the 7th to the 9th September 1798 in Canton Nidwalden, in central Switzerland. A simple version of the background to this event follows.

The Days of Terror in Nidwalden

In late January 1798 Napoleon's troops invaded Switzerland and managed to secure most of it quite quickly. That they could do so was due to the sympathies that many Swiss had for the French Revolution. Switzerland at that time was a mess of local potentates, religious bigotry and autocratic lawlessness – despite what Orson Welles famously tells us in an improvised throwaway remark in the classic film The Third Man. Switzerland was much in need of a good purge.

Napoleon was an unreliable saviour of the people: after he had looted the treasuries and taken anything else he fancied he lost interest in Switzerland and turned his attention to bigger fish. The Helvetic Republic collapsed and the Swiss went back to corrupt diversity for a while.

The French invasion had many supporters and led to the establishment of the Helvetic Republic. Switzerland being what it always was, a patchwork quilt of territories, all with their own interests, a number of communities and cantons held out against the French takeover. The French troops therefore had little or no opposition in some places, whereas in others the resistance was deep and bitter. Bitter resistance led to bitter revenge. One particular act of revenge has passed into legend.

In Canton Nidwalden on 29th August 1798 the populace rose up against the French invaders. On 9th September 10'000 French troops attacked Nidwalden from all sides. For the Swiss the situation was hopeless. An estimated 1'500 Swiss fought with a brutal determination that astonished the French. Nevertheless, the outcome was in no doubt and the French troops, enraged by the bloody resistence and fired up by wildly inflated numbers for their losses, went on the rampage in the villages and towns of Nidwalden.

Around four hundred inhabitants of Nidwalden were massacred, among them about a hundred women and twenty-six children. Farms were ruined, animals slaughtered, crops devastated, houses and churches wrecked or burned down, the inhabitants' property plundered. Countless children were orphaned.

The shock and outrage at the devastation led to a wave of sympathy and support, even from the French invaders. One of these measures resulted in the dispatch of Heinrich Pestalozzi to Stans, in Nidwalden, to organize the rescue of the orphaned children.

We mentioned Pestalozzi in passing a few years ago, but today I would like to contrast two portraits of him that recall his legendary time in Stans rescuing the orphans left after the brutalities of the 'Days of Terror'.

Konrad Grob

Here is the Swiss painter Konrad Grob's (1828-1904) depiction of Pestalozzi with the orphans of Stans.

Konrad Grob (1828-1904), Pestalozzi und die Waisen von Stans, 1879.

Image: Kunstmuseum Basel

My first impression is –Well, I wish I could paint like that!

But the more we look at the painting, the more disenchanted we become. Pestalozzi is positioned in the centre of the image, but he is overwhelmed by painterly, genre studies of children: playing, talking, reading. Pestalozzi is greeting a new arrival, whilst off to the side a widow (we assume) is bringing in her two daughters.

Because it is a genre painting it is full of details: the boy with the cloth around his head, does he have toothache? The girl on the left staring at us with a strange, undecipherable expression. In all this activity and portraiture Pestalozzi has been submerged under the crowd of orphans.

Grob was attempting this sort of thing:

Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller (1793-1865), Nach der Schule (After School), 1841. Image: ©Nationalgalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin.

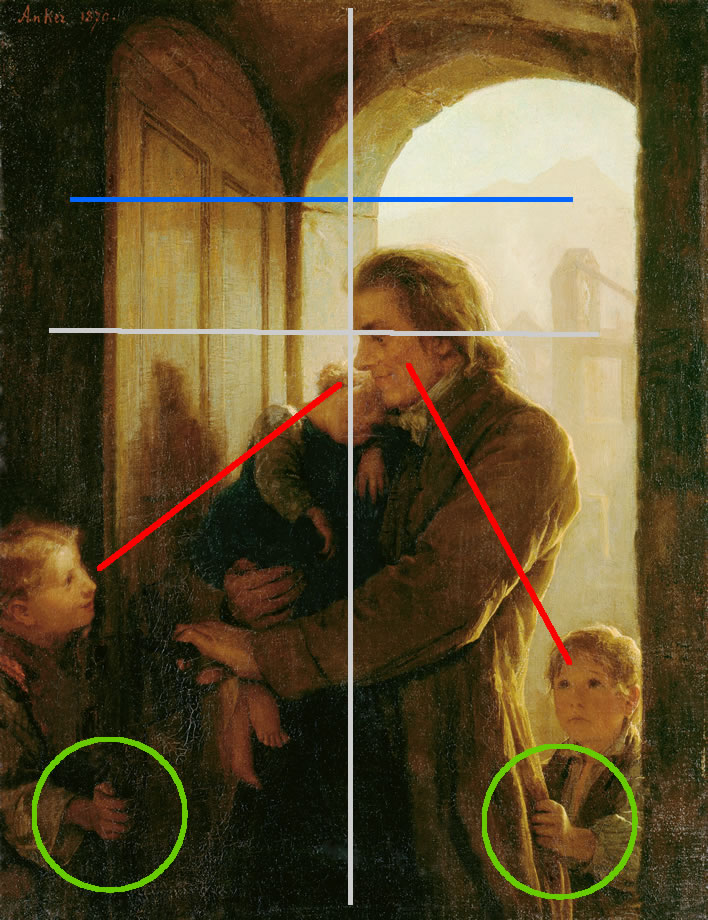

Albert Anker

We turn with relief from Grob's busy orphanage to Albert Anker's much quieter representation. Here we have Pestalozzi and three children. A smiling girl is opening the door of the orphanage for him; a young girl is asleep in his arm; behind him a young boy is holding on to Pestalozzi's coat.

Albert Anker (1831-1910), Heinrich Pestalozzi und die Waisenkinder in Stans, 1870.

Image: Kunsthaus Zürich.

The facial expressions are wonderfully well realised, particularly of the two children: the welcoming smile of the girl at the door, the anxiety and hope in the face of the boy holding on tightly to Pestalozzi's coat – he is near to rescue, but hasn't quite made it yet. Anker used children from his village as models for his work.

We see here the fear, relief and happiness of the victims, whereas in Grob's painting the anxiety quotient is very low. The widow and her two children, waiting her turn to speak to Pestalozzi, seem quite expressionless. Those waiting outside the door are just shadows, background.

We note Anker's stroke of genius in placing his subject in the doorway. No posed portrait would ever do this. Grob showed an opening door, but one without much significance, with those outside left in shadow. The shadowy figures behind Grob's half-open door are only there to tell us that Pestalozzi was in great demand.

But in Anker's painting the door is a key compositional element: outside is danger and terror, inside is safety and love (look at the faces!) and in this transition between the two states we see the pictorial representation of what Pestalozzi is doing. His hand is on the door handle – he is effecting the transition from the dangerous outside to safety of the interior. Once they are inside, the door will close and the nightmare of seeing their parents hacked to death will be left outside.

We don't need a dozen character studies of children to show us what Pestalozzi is doing, three are enough: one safe, one sleeping happily, one anxious and fearful. Through the doorway we see some very pale hints of Stans.

Since we are talking of composition, let's just take a moment to look at the way Anker put the elements of this painting together.

The vertical grey line is the vertical centre of the image. To its left is safety, to its right horror. Pestalozzi is crossing from danger to safety.

The horizontal grey line lies on the golden section. The blue line represents the movement in the painting, the transition from outside (danger) to inside (safety). In contrast, Grob's portrait is quite static with little or no movement

The red lines are the eye contact directions – they bind the picture together around Pestalozzi's face (at the golden section). Finally, we note the hands (green rings) and their symmetry: the girl's hand holds the orphanage door (security) and the boy's hand holds onto Pestalozzi's coat (hope).

Simple! It takes real genius to be this simple.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!