In Flanders Fields

Posted by Richard on UTC 2025-11-19 08:11 Updated on UTC 2025-12-21

I like writing about good (or interesting) poetry; I dislike writing about bad poetry. Most bad poetry sinks without trace anyway, so there is no need to stir up the mud at the bottom of the pond. Unfortunately, there are some bad poems that continue to bob around on the surface, refusing to sink. Let's have a look at one of these today.

One of the unfortunate rituals of Armistice Day is that John McCrae's (1872-1918) execrable poem 'In Flanders Fields' bobs up to the surface every year to annoy us. The only good thing about this event is that we only need to suffer the annoyance for a few days before the mess sinks back into the darkness in which it belongs.

The fame the poem has achieved is baffling – every year for more than a century people have declaimed and read this terrible poem with moist eyes. The poem is awful on several levels. If it were just one of the many third-rate poems in existence I wouldn't bother with it, but it is a very famous and highly regarded piece which is thrown at us once a year to much adoration. Let's take the basic grammatical/syntactical level first.

In Flanders fields (1918)

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

- Flanders fields. The location of the poem is somewhere in the fields of Flanders; thus we require the possessive apostrophe 'Flanders' fields'. There is no place called 'Flanders fields'.

- blow. In early versions the poppies 'grow', in later versions they 'blow'. 'grow' was better, since 'between the crosses' is where they grow, but 'blow' is probably thought to be more poetic.

- row on row. 'Between the crosses' is an adverbial phrase which tells us where the poppies grow; but so too does 'row on row', grammatically applying to the poppies, not the crosses. We know what McCrae is trying to say, but this is not what he does say. The contorted grammar attempts to use 'row on row' to describe the position of the crosses. In fact it describes the position of the poppies. One adverbial phrase cannot describe another adverbial phrase – as the name suggests, it needs to be attached to a verb, for example: Between the crosses, [which are laid out] row on row.

- That mark our place. The subject is 'the crosses' (plural) which 'mark' (plural) 'our place' (singular). This should surely be 'our places', unless the entire battlefield cemetery is meant.

- bravely. I know this is a war poem, but we can be certain that the larks are not singing 'bravely' (Ruskin's 'pathetic fallacy').

- Scarce heard amid the guns below. 'Scarce heard' is yet another misplaced adverbial phrase. Grammatically it applies to the verb 'fly', suggesting that the larks' flying was scarce heard, which is nonsense – what was scarce heard was the larks' singing. The solution might be to see it as applying to the singing larks more generally, but this just transfers us from the frying pan into the fire. The larks' flying is not 'scarce heard amid the guns below', but their singing. But then we have to deal with the curious word 'below', which contradicts the word 'amid'. The larks can't be amid and above the same thing at the same time. One would normally assume that the larks were singing 'above' [the battlefield] but their song could not be heard 'below' [where the guns are firing]. We might argue that 'scarce heard' applies to the larks – except we don't hear larks, we hear their singing. This line is even more of a mess than my explanation of it, the latter having caused some readers to be reaching for the smelling salts.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

- Short days ago. 'Short days' must refer to the length of the days, but it seems to be used as a synonym for 'a few days ago [we lived]', the 'ago' requiring a period of time (e.g. a number, or 'a few') measured in days.

- felt dawn. Can one 'feel' dawn? It appears to be just a poetism to avoid using the word 'saw' twice.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

- our quarrel with the foe. What quarrel did the soldiers who died have with the foe? The 'quarrel' – if one can use such an unsuitable word – was between the governments of the United Kingdom and its Empire and the German Empire. The soldiers' bodies merely got in the way of the hardware of the meatgrinder. Occasionally during the last century or so readers have noticed that McCrae's 'sad war poem' is in fact extremely militaristic, calling as it does for even more men to be thrust into the meatgrinder. As the war ground on, the poem was even used as a recruiting aid for new meat for the grinder.

- be yours. 'Be yours to hold it high' is grammatical nonsense. We can only guess that it is intended to mean 'the torch is yours to hold high'

- ye. Why this archaism now? What's wrong with 'you'?

- break faith. What 'faith' has to be kept? Is making peace 'breaking faith'? Are all armies morally bound to fight to the last man? McCrae is an idiot.

- sleep. The dead do not sleep. One would think that an army doctor would not imagine that the mutilated and shredded corpses of the fallen are 'asleep'. If the dead do not 'sleep' because the survivors 'broke faith', what do they do? Haunt the cemetery?

- though. 'Though' is a conjunction that links 'sleep' with 'poppies growing'. It makes no sense. If this is not immediately clear, try substituting a synonym of 'though' such as 'we shall not sleep despite the fact that poppies grow'. The statement is absurd.

The reader will appreciate what a thankless task it is to inspect a poem at this most basic level of meaning. But this poem deserves it, because the alert reader stumbles over one blemish after another. It does not deserve its fame. Its emotional impact on the superficial reader comes from a series of dog-whistle words for the susceptible: 'Flanders fields', 'poppies', 'crosses', 'larks', 'guns' etc. The tears welling up in the reader's eyes obscure the fact that the words around the dog-whistles make little sense.

Why is this poem such a mess?

John McCrae is a poor quality poet is the short answer. The longer answer would add that he chose a verse form that was far beyond his talent.

Both of these answers are supported by one account of the genesis of the poem, which tells us that McCrae was dissatisfied with it and fiddled about with it for nearly two months before it was published. If this is true, then it indicates that McCrae could see its defects but lacked the will or skill to improve it.

A kinder answer would say that the first answer may be correct, but that in his defence we should note that he wrote the poem in a very challenging verse form, the rondeau. McCrae didn't have the talent to handle this difficult form. What makes it worse is that the form itself is highly unsuitable for the serious theme of the poem. In order to demonstrate this, readers are in for a bit of a bumpy poetic ride.

Some formes fixes

The rondeau, the verse form that McCrae chose for 'In Flanders Fields', is one of a collection of verse forms known by the French term formes fixes, implying that the characteristically French forms are pre-defined and that poets that use them have to stick by the rules of metre and rhyme scheme.

How did the French formes fixes arise and how did they get into English poetry?

After William the Conqueror's invasion of England in 1066 there followed several generations in which the language of the conquerors, French, (a romance language, Latin based) was mixed with the Germanic languages of the conquered. Many Germanic words remained in use in the language of the common people. Many of them are still with us today in words for everyday objects such as 'glass' (Glas) and 'stool' (Stuhl). The peasant may still sit on his Germanic stool, but his feudal lord would plant his bottom on a 'chair' (chaise, formerly chaire in older French). The rule has its exceptions, of course, but it is good enough: everyday things and ideas, Germanic; elevated things and ideas, French.

In France, during the Medieval Warm Period (~900..~1200 AD), a high culture grew up, a culture of castles built in high places, of literary production and of poetry. Its poetic peak came with the troubadours in Provence, a region overflowing with riches. Provence was the language hotbed of the Romance languages; in addition to the French lands to the north, its neighbours were Spain and northern Italy. The troubadours walked the remains of the long Roman roads between all the limits of the region.

Much of this intellectual life was never written down and is lost to us, but what we have suggests the existence of a very high literary culture. In a flourishing civilisation there is spare money – money in excess of the needs of survival – that could support cultural pursuits, among them wandering poet-musicians. Once there are enough of these they create their own competitive culture, in which its members strive to outdo their rivals and attract the favour of a generous patron.

In a time of widespread illiteracy, even among the great and the good, poetry was not read but recited, or more usually, sung. Some verse forms crystallised out – then as now, people were happy with the comfortingly familiar. New forms developed through a competitive spirit. The adherence to the formes fixes was a test of a poet's skill.

As far as we can tell, the peak of this development was reached in the poetry of Arnaut Daniel, whose trobar clus ('closed rhymes') achieved a complex virtuosity. His poems mark the high point of poetic development in Provencale. Whereas Arnaut Daniel pulled out all the stops in his verse, his contemporaries used the troubadour forms as a medium of entertainment – light-hearted, much concerned with courtly love and the adoration of the Lady. They had to give their patrons and listeners what they wanted: amusement.

Arnaut is associated with the sestina, a forme fixe poem of six stanzas of six lines plus a final three line stanza. The specification of the rhyme scheme is beyond the understanding of normal humans, although when written down it is reminiscent of the vectors used in quantum mechanics. Here be dragons!

All of the verse that was created in this poetic hothouse relies on the particular characteristics of the Romance languages, in particular the ease of finding end-rhymes. We note here that modern German has this facility too. English, with its mongrel origins, is not as forgiving. In English, you can usually find a rhyme, but whether the rhyming word means what you want to say is another matter – often it doesn't.

The Provencale culture was obliterated by the French in the north, ostensibly in a religious crusade against the Albigensian heretics (1209-1229), but, as is almost always the case, the religious crusade was largely a pretext for a land grab and an economic and cultural conquest. If Provence had been a poor region, no one would have bothered with it, whatever religious woo-woo had taken root there.

French absorbed the poetry of Provence and adapted it to its own taste. In England, after a couple of centuries of French integration following the conquest, these troubadour models, the formes fixes, were brought into England, bearing the prestige of the great cultural epiphany from whence they came.

Austin Dobson, a few of whose poems we shall look at below, had a chapter in his Complete Works (1923) entitled 'Essays in Old French Forms' (27 pages containing 37 poems; 'essays' having the French meaning of 'attempts'). Unfortunately, the formes fixes are inimical to English, with its lack of easy end-rhyming. They also encouraged the cultivation of form over substance.

The collection of formes fixes begins with short forms, of which the triolet is an example, and moves up to the rondeau (McCrae's chosen form) and beyond in length and complexity. This lengthy excursion is necessary to show the poetic trench warfare that McCrae got tangled up in by choosing the fashionable rondeau as the form to use for his 'Flanders' Fields' poem.

The Triolet

The triolet is the shortest of the traditional formes fixes. It consists of eight lines; only two different rhymes are permitted; the first line is repeated as the fourth line; line 1 and 2 are repeated verbatim as line 7 and 8. Here is an example by the American scribbler Henry Cuyler Bunner (1855-1896):

A Pitcher of Mignonette (n.d.)

A pitcher of mignonette,

in a tenement's highest casement:

Queer sort of flower-pot — yet

That pitcher of mignonette

Is a garden in heaven set,

To the little sick child in the basement

The pitcher of mignonette,

In the tenement's highest casement.

Henry Cuyler Bunner, The Poems of H. C. Bunner, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1912, p. 35.

I chose this example not because it is perfect, but because it violates the rules: Bunner has varied the text of the repeated lines:

A pitcher of mignonette

That pitcher of mignonette

The pitcher of mignonette,

Bunner could have easily standardised the line by using 'that pitcher' throughout; perhaps he though that sounded too mechanical, but such are the dangers of the formes fixes. Nevertheless, Bunner did a good job getting some meaning into this strange structure. That said, the triolet is not a particularly difficult form: once you have thought out the first two lines, most of the rest of the poem writes itself in the repeats.

Here's another example, this time from Austin Dobson (1840-1921); formally perfect and illustrating the lightness of subject for the triolet:

A kiss (n.d.)

Rose kissed me today.

Will she kiss me tomorrow?

Let it be as it may,

Rose kissed me today;

But the pleasure soon gives way

To a savour of sorrow;

Rose kissed me today

Will she kiss me tomorrow?

(Henry) Austin Dobson, from 'Essays in Old French Forms' in The Complete Poetical Works of Austin Dobson, Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1923, p. 323.

We'll end our look at the triolet with a robust counterblast from Andrew Barton 'Banjo' Paterson (1864-1941), Australian literary hero, whom the world knows as the author of the lyrics to 'Waltzing Matilda', written in 1895. It is fair to say that he did not like the triolet at all:

A Triolet (1894)

Of all the sickly forms of verse,

Commend me to the triolet.

It makes bad writers somewhat worse:

Of all the sickly forms of verse,

That fall beneath a reader's curse,

It is the feeblest jingle yet.

Of all the sickly forms of verse,

Commend me to the triolet.

A. B. 'Banjo' Paterson, 'A Triolet', first published in The Bulletin, 13 January 1894, collected in Complete Works 1885-1900, Volume 'Singer of the bush', ed. Rosamund Campbell and Philippa Harvie, 1985, p. 209.

The Rondeau

Our next stop on the journey into the formes fixes empyrean is the rondeau, the form over which John McCrae came a cropper. The rondeau consists of 15 lines, of which 13 are full lines and two half-line refrains repeated from line 1. The lines are usually grouped in three stanzas, the first of five lines, the second of three lines plus a refrain and the third of five lines and a refrain. Once again, there are only two rhymes. The situation will be clear from the following example, 'You bid me try', another heroic effort by Austin Dobson:

'You bid me try' (1876)

You bid me try, BLUE-EYES, to write

A Rondeau. What! — forthwith? — tonight?

Reflect. Some skill I have, 'tis true;—

But thirteen lines! — and rimed on two!

'Refrain' as well. Ah, hapless plight!

Still, there are five lines — ranged aright.

These Gallic bonds, I feared, would fright

My easy Muse. They did, till you —

You bid me try!

That makes them eight. The port's in sight;—

'Tis all because your eyes are bright!

Now just a pair to end in 'oo' —

When maids command, what can't we do?

Behold! — the RONDEAU, tasteful, light,

You bid me try!

(Henry) Austin Dobson, from 'Essays in Old French Forms' in The Complete Poetical Works of Austin Dobson, Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1923, p. 327.

This ticks all the boxes for the rondeau ('tasteful, light') – formally correct, but light, elegant and whimsical. The poetic trickery required to put a rondeau together leaves no room for deep and sombre thoughts about life and death and war and patriotism.

It takes a competent poet to avoid disaster – even a scribbler of the calibre of Austin Dobson occasionally hits the buffers: In his rondeau 'The Wanderer' (1880) he was forced to come up with 'who shall help us from over-spelling / That sweet forgotten, forbidden lore' to get him out of a rhyme-scheme trap.

The Roundel

That great master of versification, Swinburne, invented his own variant of the rondeau, which he called the 'roundel'. Whereas even a competent poetic plodder would be happy to get two or three rondeaux over the line, Swinburne, bursting with easy talent, filled a book with one hundred of his roundels, all of excellent quality. John McCrae is simply not in this league. Here's the roundel Swinburne wrote about the roundel:

'The Roundel' (c.1892)

A roundel is wrought as a ring or a starbright sphere,

With craft of delight and with cunning of sound unsought,

That the heart of the hearer may smile if to pleasure his ear

A roundel is wrought.

Its jewel of music is carven of all or of aught —

Love, laughter, or mourning — remembrance of rapture or fear—

That fancy may fashion to hang in the ear of thought.

As a bird's quick song runs round, and the hearts in us hear

Pause answer to pause, and again the same strain caught,

So moves the device whence, round as a pearl or tear,

A roundel is wrought.

Algernon Charles Swinburne, A Century of Roundels, Chatto & Windus, London, 1892, p. 63.

The reader will find no deep meaning in Swinburne's roundel, but that was never the point of the formes fixes, even in Provence – they are really just there to show off your skills to your audience. Swinburne, particularly when he'd had a few, was the Chopin of versification.

The villanelle

Consisting of 19 lines, the villanelle is longer than the rondeau. It is broken up into five three-line stanzas and a concluding four-line stanza. There is a rather complicated order of refrains. Like all the other formes fixes that we have looked at, only two rhymes are allowed. The villanelle certainly presents a challenge not only to meet its structural and metrical requirements but at the same time to make sense. To cheer us up at the end of our long journey through the formes fixes let's take Ernest Dowson's wonderful and justifiably famous 'Villanelle Of The Poet's Road':

Villanelle Of The Poet's Road (1899)

Wine and woman and song,

Three things garnish our way:

Yet is day over long.

Lest we do our youth wrong,

Gather them while we may:

Wine and woman and song.

Three things render us strong,

Vine leaves, kisses and bay;

Yet is day over long.

Unto us they belong,

Us the bitter and gay,

Wine and woman and song.

We, as we pass along,

Are sad that they will not stay;

Yet is day over long.

Fruits and flowers among,

What is better than they:

Wine and woman and song?

Yet is day over long.

Ernest (Christopher) Dowson (1867-1900), 'Villanelle Of The Poet's Road', in Decorations in Verse and Prose (1899), then in The Poems and Prose of Ernest Dowson, John Lane The Bodley Head Ltd., London, 1900, p. 129.

In this villanelle, Dowson, a masterful versifier, much like an accomplished pianist making a tricky composition sound easy, copes with all the tricks and difficulties of the form so well that the reader barely notices them.

The many repetitions required by the villanelle form – 'Wine and woman and song' and 'Yet is day over long' – serve to emphasise the main message of the poem; the rhyme-words are normal words, there is nothing about them that feels contrived; the syntax is normal and without affectation; the overall tone of the poem is cheerfully elegaic, demonstrating that the longer formes fixes at least can cope with quite serious themes in the hands of a master.

Curious readers might like to contrast Dowson's command of the villanelle with Dylan Thomas' (1914–1953) execrable effort, 'Do not go gentle into that good night' – doggerel that I cannot bring myself to reproduce here.

Dylan Thomas, John McCrae and numerous third-raters, lacking skill and talent, foundered on the exigencies of the long formes fixes such as the villanelle and the rondeau.

Third-rate poets pick a form and then have to bend and twist vocabulary, syntax and grammar to get their words into it – the almost inevitable consequence is that in battering the rhymes and metre into the artificiality of the form, the flow of ideas is lost (if it was ever there in the first place).

Why McCrae, viewing the mangled corpses of the slaughtered, should choose the rondeau, a late medieval French dance form, to express his feelings is a mystery – certainly to me.

W.B. Yeats, one of the greatest poets of the twentieth century, had cut his poetic teeth among the verbal acrobats and show-offs of the nineteenth century fin de siècle. But he knew better when it came to writing serious verse: his method of composition was first to write out the poem-to-be in the form of a prose narrative. This brought together all the ideas of the piece and created the rhetorical and syntactical scaffolding around which the poem would be built. Yeats' magnificently subtle masterpiece Easter 1916 explores the 'terrible beauty' of fanaticism in a poem about pointless death, pointless heroism and stupidity. Compare that with McCrae's jingoistic rubbish. There is no comparison.

The poppies of 'Flanders Field'

My shame at writing so much about a short poem was so great that by the time I got to 3'000 words, the scribbling had to stop. I posted the article and went for a walk. My shame wasn't over - I kept thinking, surely I should have at least praised the otherwise useless poet McCrae for a first line that certainly caught the public imagination and even seemed to have created a meme (as we say these days) which associated the blood-red poppies of the fields of Flanders with the slaughter of the Great War. That's worth a stroke, is it not?

Well, the other day I discovered in Donald Pittenger's fascinating illustration blog Art Contrarian, which I have followed for some years now, that an American artist, Robert William Vonnoh (1858-1933) had painted a scene he intially titled 'In Flanders Field' in 1890, subtitled at some point Coquelicots (Coquelicots is the French name for the red poppies often seen in fields of corn). Vonnoh was often said to be the 'American Impressionist'. I had never heard of him. Pittinger also admits: 'Until recently, I had never heard of him'.

Robert Vonnah, In Flanders Field, 1890. The density of the poppies strikes me as overdone – over-egging the custard, in fact. Monet's colony of poppies (below) are much more realistic. Image: Current location unknown (to me).

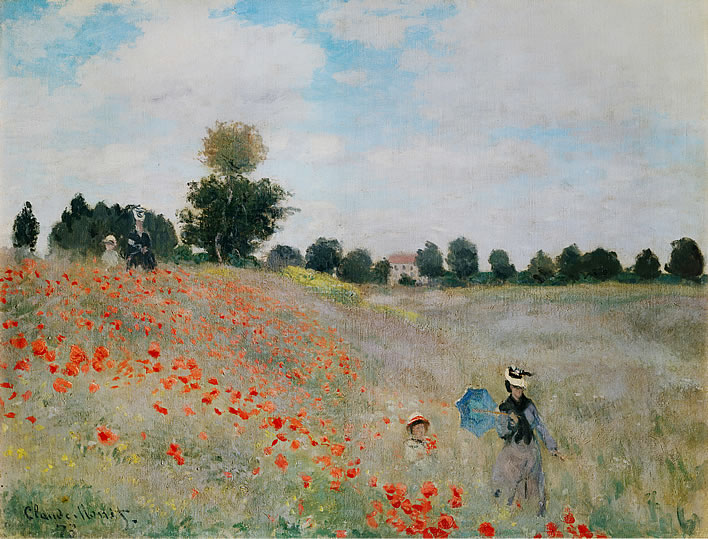

Despite his present obscurity, Vonnoh was popular in his day and his painting 'In Flanders Field' was extremely well known at the time – in fact it was his most famous work by far. Summer fields with poppies were a staple of the Impressionists cookbook – Claude Monet painted several, the best known one being Les Coquelicots in 1873. Despite the popularity of Flanders Field Vonnoh's painting took a long time to sell.

Claude Monet, Coquelicots, La promenade, 1873. Image: Musée d'Orsay, Paris

So let's have a timeline. As I have noted here on several occasions, I do like a nice timeline.

- 1873— Claude Monet is painting fields of poppies, e.g. Les Coquelicots.

- 1890— Monet's fanboy Robert Vonnoh paints In Flanders[sic] Field. The painting is sometimes referred to as Coquelicots, presumably in homage to its inspiration, Claude Monet.

- 1914— Start of the First World War.

- 1915-16— Fighting in Flanders and northern France.

- 1915— John McCrae writes In Flanders[sic] Fields. The shared grammatical error in the titles of the painting and the poem make it extremely probable that McCrae was alluding to Vonnoh's painting. The only difference is that McCrae makes 'Field' plural.

- 1918— McCrae dies of pneumonia. End of the First World War. McCrae's poem is already on its journey to icon status, boosted by its usefulness as a recruiting anthem for the still hesitant.

- 1919— Vonnoh's painting In Flanders[sic] Field finally sells, presumably boosted by the popularity of McCrae's poem.

- 1919?— At some point Vonnoh's painting acquires an alternative title, Where Soldiers Sleep and Poppies Grow. There can hardly be any doubt that this additional title came from the 'sleeping' dead in McCrae's poem. Applied to Vonnah's painting, it makes no sense at all.

So, summa summarum, it seems likely that John McCrae got his cracking first line from the title of Robert Vonnoh's very popular painting, defective grammar and all. We have to give McCrae the credit for seeing the symbolic interpretation of Vonnoh's idyllic painting of fields which were now covering the dead. We can imagine McCrae, with Vonnoh's painting in his mind, looking out over the churned battlefields and their graves.

Update 21.12.2025

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!