No Man's Land

Richard Law, UTC 2025-11-09 14:19

11 November is Armistice Day (in the United Kingdom or Remembrance Day or Veterans' Day elsewhere). On this theme, therefore:

Robert Frost, [No Man's Land] (1902)

The battle rent a cobweb diamond-strung

And cut a flower beside a ground bird's nest

Before it stained a single human breast.

The stricken flower bent double and so hung.

And still the bird revisited her young.

A butterfly its fall had dispossessed

A moment sought in air his flower of rest,

Then lightly stooped to it and fluttering clung.

On the bare upland pasture there had spread

O'ernight 'twixt mullein stalks a wheel of thread

And straining cables wet with silver dew.

A sudden passing bullet shook it dry.

The indwelling spider ran to greet the fly,

But finding nothing, sullenly withdrew.

Robert Frost, 'Range-finding' in Mountain Interval, New York, Henry Holt, 1921. p. 36. The book was first published in 1916, then, with alterations in 1920 and again, with alterations in 1924.

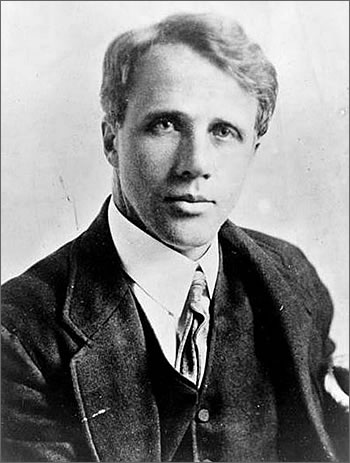

Robert Frost, 1910-1920.

Range-finding

Knowledgeable fans of Robert Frost will notice with shock that I have retitled Frost's poem. Its canonical title is 'Range-finding'.

This title is predestined to baffle any reader; those who enquire further will encounter much incomprehensible blather from literary types about Frost's concept of 'ranges' – 'zones of perception' if you like. In brief, this is the idea that much of the natural (non-human) world and the lives of its inhabitants are beyond the perceptual and cognitive abilities of humans – and, of course, vice-versa. These 'ranges' go their separate ways, except for occasional interactions. Out of sight, out of mind, in other words.

Readers with long memories will recall our comment on the great mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal's (1623-1662) formulation in his Pensées of the 'barriers' that limit human perception and cognition – in effect an alternative description of Frost's 'ranges':

Limited as we are in every faculty, our powers are to be found in the mean between two extremes. Our senses cannot perceive extremes: too much sound deafens us; too much light dazzles us; too great a distance or too close a proximity obstructs our view. Both too great a length or too great a brevity of discourse obscures meaning; too much truth shocks.

Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), Pensées sur la religion et sur quelques autres sujets, Transition XV, 199-72 H, Disproportion de l'homme, 9. - Voilà où nous mènent les connaissances naturelles. Les Pensées de Blaise Pascal

Frost described such an occasional interaction in his fine poem 'A Considerable Speck (Microscopic)', which we discussed almost exactly five years ago.

Frost's title 'Range-finding' was intended to hint at the overlapping 'ranges' of interactions between the human and the natural world. Neither the bird nor the butterfly can perceive or understand the danger they are in – the bird returns to its nest on the ground, the butterfly to its chosen flower. That danger is in a different 'range' of reality which they cannot comprehend. The human shooter is oblivious to the 'range' which his bullet has affected. Once you grasp this idea, the poem becomes a little bit clearer, but at the same time a little bit problematic.

The purpose of 'range-finding' is not to kill the enemy, but to establish the correct aim of the gun required to hit the target at a certain distance. However, when Frost writes 'Before it stained a single human breast', he refers to something which is not, strictly speaking, the purpose of range-finding. The interior world of a poem has to be coherent: the dissonance between the title and the wounded human causes the alert reader some puzzlement.

Once the title 'Range-finding' is out of the way, the poem does not need any explanation, apart perhaps from 'mullein' (Verbascum), a plant with a long (up to 3 metres) flowering stem that arises from a rosette of leaves at ground level – perfect for spiders' webs!

The not quite a sonnet

Leaving the problem with the title 'Range-finding' aside, the poem itself is a fine piece of poetic craftsmanship. It is a pity that the flawed title causes us so much bother.

The poem takes the form of a Petrarchan sonnet, which is a poem in two parts: an octave of eight lines followed by a sestet of six lines. The rhyme scheme is strictly observed in the octave (ABBAABBA), but, like many other examples, allows some latitude in the sestet (CCDEED).

The only blemish for those that care about such things is the fact that in Frost's poem the sestet does not offer the expected conclusion – or 'wrapping up', in other words – of the ideas expounded in the octave. It is formally correct in many ways, but lacking in the larger structure, which is the characteristic that has made the sonnet such a popular verse form down the ages: the macro-structure of proposition (octave) and resolution (sestet), the latter opening with a distinction (volta) and closing with a conclusion.

For example, take Wordsworth's famous Petrarchen sonnet, 'London, 1802', a model of its kind:

Octave [proposition: England is going to Hell in a handcart]

Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour:

England hath need of thee: she is a fen

Of stagnant waters: altar, sword, and pen,

Fireside, the heroic wealth of hall and bower,

Have forfeited their ancient English dower

Of inward happiness. We are selfish men;

Oh! raise us up, return to us again;

And give us manners, virtue, freedom, power.

Sestet [resolution: Milton the saviour's fine qualities]

Thy soul was like a Star, and dwelt apart; [volta]

Thou hadst a voice whose sound was like the sea:

Pure as the naked heavens, majestic, free,

So didst thou travel on life's common way,

In cheerful godliness; and yet thy heart

The lowliest duties on herself did lay.

Shakespeare played a major part in the development of the Petrarchen (Italian) sonnet into the English sonnet, more specifically into the characteristic Shakespearean sonnet. Let's look at his most famous sonnet, 'Sonnet 18':

Octave [proposition: beauty is changeable]

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer's lease hath all too short a date:

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature's changing course, untrimmed:

Sestet-Quatrain [resolution: your beauty preserved by my poetry]

But thy eternal summer shall not fade, [volta]

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow'st;

Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade

When in eternal lines to time thou grow'st:

Sestet-Couplet [wrap-up: my poetry will immortalise you]

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

It is exactly the macro-structure of the sonnet which is missing in Robert Frost's 'Range-finding'. The line counting is correct, the rhymes are where we expect them to be, but the opposition and resolution that is the essence of the sonnet is missing. Instead we get two component scenes strung out one after the other: the busy scene with bullet, cobweb, flower, bird and butterfly bound together in complex syntax, followed by almost a repetition, the syntactically much simpler scene with the bullet and the spider.

Overlooking the pathetic fallacy of the 'sullen' spider, each of the two components is fine versification, but the second just restates the first in a slightly different way.

Only pedants like me will mutter about the neglect of the traditional form. I don't know, but it may be that dissatisfaction with the formal aspects of the work caused Frost to leave it unpublished for some years. Even later in life, Frost chose not to make an audio recording of 'Range-finding', although he recorded numerous other works. He was a craftsman poet and if I can see the defects, he certainly could, too.

'Range-finding' preserved, possibly unwillingly

The poem was written in 1902, at a time of prevailing peace in the West, although the Civil War battlefields were still fresh in Americans' memories and the Boer War had only just concluded in 1902. In another dozen years, as ever, 'the Cannibals of Europe [would be] going to eating one another again' (©Thomas Jefferson) For some reason, as noted above, Frost seemed not to be happy with the poem and it lay fallow in manuscript form for more than a decade.

Frost's close friend, the writer and poet (Philip) Edward Thomas (1878-1917) served in the First World War (1914-1918) and met his end as a second lieutenant on 9 April 1917, the first day of the Battle of Arras. He had spent scarcely two months in France before he was killed. He told Frost that he thought 'Range-finding' was a good representation of the no man's lands of trench warfare.

Edward Thomas in uniform, ND.

Since this piece is being published for Armistice Day it is fitting to note that the Battle of Arras was yet another costly stalemate in an insane war: within a few weeks the meatgrinder got through nearly 300'000 casualties on both sides, about 50'000 of which were deaths.

There are accounts from the troops advancing across the wide spaces of no man's land on the Somme battlefields under intense machine gun fire which describe how the hail of bullets could not be seen, except for the puffs of 'smoke' when they struck and pulverised cereal crops or standing flowers. This phenomenon only lasted until artillery bombardments had churned up the ground. In a striking coincidence, as we now know, Thomas was killed by a shot to the chest ('it stained a single human breast').

Edward Thomas's favourable opinion of the poem gave new life to the defective original by turning it into a war poem – a rather scrappy war poem into which everything fits except the title. Perhaps Frost published it as a memorial to his great friend, after which piety prevented him removing it or changing it. Who knows? Despite my pedantry – which I suspect was shared by Frost – it says a lot for the quality of the poem that once we throw out the strange title, the rest of the poem is crystal clear and accessible to any reader with a bit of thought. Just don't call it a sonnet.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!