Die Winterreise, Chapter 3

Richard Law, UTC 2015-12-31 16:13

Chapter 3 – Poems 13-24

An analysis of the final twelve poems of Die Winterreise. Schubert designated these as the 2. Abtheilung, 'second section'. It contains the following poems/songs.

13 Die Post (Von der Straße her ein Posthorn klingt…)

14 Der greise Kopf (Der Reif hat einen weißen Schein…)

15 Die Krähe (Eine Krähe war mit mir…)

16 Letzte Hoffnung (Hie und da ist an den Bäumen…)

17 Im Dorfe (Es bellen die Hunde, es rasseln die Ketten…)

18 Der stürmische Morgen (Wie hat der Sturm zerrissen…)

19 Täuschung (Ein Licht tanzt freundlich vor mir her…)

20 Der Wegweiser (Was vermeid’ ich denn die Wege…)

21 Das Wirtshaus (Auf einen Todtenacker…)

22 Muth! (Fliegt der Schnee mir in’s Gesicht…)

23 Die Nebensonnen (Drei Sonnen sah ich am Himmel steh’n…)

24 Der Leiermann (Drüben hinterm Dorfe…)

Conclusion, Chapter 3, poems 13-24

13 Die Post (Von der Straße her ein Posthorn klingt…).

I hear a posthorn sound from the road. What has made you jump so high, my heart? The post does not have any letters for you, so why are you so excited, my heart? Well, the post is coming from the town where I used to have a loved one, my heart! Do you just want to look over there and ask how things are going, my heart?

Notes

- This poem picks up on a theme raised in poem 4, 'Erstarrung': the image of the loved one frozen hard into the narrator's heart, an image that will only disappear when the heart melts. 'Die Post' can be seen a status report on this process: the narrator's heart is still yearning for the loved one, despite betrayal and rejection.

- Schubert picked up the galloping rhythm and set the poem perfectly to music. This song has been a popular piece for standalone performance, giving singers – particularly romantic tenors – plenty of scope for virtuosity. Unlike poem 5, 'Der Lindenbaum', the narrative of the poem is largely self-contained and the song can be performed as a single piece without difficulty.

- The problem for us is: how and where does it fit into Die Winterreise? The last poem of the first section, 'Einsamkeit', left the narrator wandering through a world that was reawakening after winter, but still full of alienation from that world. The bouncing metre of 'Die Post' is difficult to reconcile with everything that has gone before and things that are yet to come in the Schubert's ordering of the cycle.

- By the end of the first section the narrator has disposed of any affection he had for the girl. She betrayed him and rejected him. In the course of the first section he has purged himself of her. 'Die Post' is the only poem in the second section that recalls her memory. It also suggests that his heart is still in love with her. In the poems that follow in the second section there is no resolution of this state. In the Schubertian position of the poem its depiction of a reawakening of longing jars.

- Perhaps it is significant that in Müller's rearrangement in 'Waldhornist' he positioned 'Die Post' to follow poem 5, 'Der Lindenbaum', which in turn followed poem 4, 'Erstarrung'. In other words, 'Die Post' and 'Erstarrung' were much closer together. 'Die Post' was one of the last two poems (the other was poem 19, 'Täuschung') that Müller added to his collection. It only appeared in the final collection of the cycle in 'Waldhornist'. In this position 'Die Post' sits much more comfortably in the narrative, certainly more comfortably than it does at the start of Schubert's second section.

- At the end of poem 5, 'Der Lindenbaum' the narrator is a few hours away from the town. When Müller's places 'Die Post' after it, the proximity of the narrator's position to a road with a post-coach is feasible, as is the desire of the narrator's heart to just 'look over' to the nearby town.

- The questions the narrator poses to his heart in 'Die Post' are answered in one of the poems that follows it in Müller's sequence, poem 7, 'Auf dem Flusse': Mein Herz, in diesem Bache / Erkennst du nun dein Bild? / Ob's unter seiner Rinde / Wohl auch so reißend schwillt?, 'I ask my heart whether it can see its image in the stream and whether under its icy crust the stream is also in as much turmoil [as my heart is]'. In other words, his heart should calm down and do what the stream has done under the icy cover it has laid over itself – just 'lie cold and unmoving, stretched out in the sand'. The narrator just wants to forget the girl who hurt him and betrayed him.

- The narrative difficulty with Schubert's assignment of 'Die Post' to the start of the second section is that by then the narrator has journeyed away from the town where his loved one lives. Hearing a post-coach on a road coming from that town is always possible, but, given the separation from the town that we have experienced so far the suggestion that the heart should be able to just 'look over' to the nearby town is unsettling.

- In sum it seems to the present writer that it would have been better if Schubert had adopted Müller's position for 'Die Post'. I would suggest that the difficulties of the Schubert location and the breezy galloping accompaniment are such that Die Winterreise as a cycle would benefit if the song were either sung in the position to which Müller assigned it or be omitted completely, leaving it as a freestanding song for tenors to do with as they wish.

14 Der greise Kopf (Der Reif hat einen weißen Schein…).

Jack Frost had sprinkled a white glow over my hair, which made me think I had already become an old man. I felt very happy about that. But it soon thawed away and now I have black hair once again; my youthfulness is a shock. How long I am going to have to wait for my funeral bier! Some heads go grey in the time between the red of evening and the light of morning. Who believes that? And my hair has not turned white throughout this whole journey.

Notes

- There is no specific narrative place or time in this poem.

- This poem contrasts his physical state with his mental state. He feels so miserable in his mind that his physical youth comes as a shock. He is shocked at the thought of the length of time his body may survive although his mind is ready for death (=he would be happy to be an old man and is ready for his end).

- The misery of his journey so far seems to have had no effect on him physically. How can he believe the tales of people 'going grey overnight' when all his terrible suffering seems to have had no effect?

15 Die Krähe (Eine Krähe war mit mir…).

A crow has accompanied me ever since I left the town. It has flown around my head again and again. Crow, you strange creature, will you not leave me? Are you just waiting until you can feast on my corpse? Well, there is not much further to go with my [wander-]staff. Crow, just let me finally see loyalty endure until the grave!

Notes

- The reference to the departure from the town implies a narrative time, but there is no specific narrative place in this poem.

- The narrator memorably told us in poem 8, 'Rückblick', that the crows had thrown things at him as he was leaving the town. It now appears that one of them has followed him ever since.

- The crow is known as an eater of carrion – the flesh of corpses – and so, of course, the narrator assumes that the crow is just waiting for his (imminent) demise.

- The narrator calls the crow a wunderliches Tier, a strange, even magical animal. Crows (and all the other members of the Corvus genus such as raven, jackdaws and jays) are intelligent creatures and in sagas and legends many supernatural properties and feats are attributed to them. For example, in 861 two vagabonds murdered the hermit St. Meinrad in his cell near Einsiedeln in Switzerland. They made off but were followed by two ravens who circled above them. The presence of the ravens allowed the authorities to identify the murderers, who were then burnt at the stake.

- On the one hand the narrator is unsettled by the crow's ominous, almost supernatural attachment to him; on the other the constancy of the crow as a companion has impressed him. If the crow accompanies him until his death at least one creature will have shown loyalty and constancy to him, unlike the human family he has left.

- Our principle of reading the text that is there and not what we imagine to be there serves us especially well in this poem. Some commentators have read the phrase Treue bis zum Grabe!, 'loyalty until the grave' as being some allusion to the marriage liturgy bis dass der Tod euch scheidet, 'till death us do part'. Marriage was an unfulfilled liturgical act for our narrator. But since this formula did not appear in the German marriage liturgy – neither Roman Catholic nor Protestant – until well after Müller's time we can dismiss this as just another fantasy reading among the many that have attached themselves to The Winterreise.

16 Letzte Hoffnung (Hie und da ist an den Bäumen…).

Here and there in the trees a colourful leaf can still be seen. And I stand in front of the trees deep in thought. I look at a one single leaf and hang my hopes on it. If the wind plays with my leaf I tremble as much as I can. Oh, and if that leaf falls to the ground, my hopes fall with it. I likewise fall to the ground and cry on the grave of my hopes.

Notes

- There is no specific narrative place or time in this poem.

- The narrator shows us his gambler's soul: he associates his hopes for happiness with the behaviour of the leaf. If, during the time he observes it, the leaf falls to the ground, then he has lost. Humans do the same thing with card games, horse races and lotteries, assigning their destiny to an impersonal fate. For a gambler, winning means acceptance, almost a blessing, and losing means rejection – until the next time, of course.

- To 'cry on the grave of my hopes' in this context means to cry over the leaf on the spot where it has fallen.

17 Im Dorfe (Es bellen die Hunde, es rasseln die Ketten…).

The dogs in the village bark and their chains rattle. The inhabitants snore in their beds, dream of things they do not have, wallow in good and troubled [thoughts]: in the morning it has all vanished – ah well, they have enjoyed their part and they hope that everything [that remains undreamed] will be found again on their pillows. Just bark me away, you wakeful dogs, don't let me rest in the sleepy hours! I'm finished with all my dreams - why should I linger among sleeping people?

Notes

- The narrator is passing through a village at night.

- Schubert softened Müller's robust phrase Die Menschen schnarchen in ihren Betten, 'People are snoring in their beds', to Es schlafen die Menschen in ihren Betten, 'People are sleeping in their beds'. A pity, really, since the narrator's dislike of his fellow humans is emphasised by his image of them snoring in bed. We might even imagine that our narrator hears this racket as he is passing by. (As it was then, so it is now.) The only reason for Schubert's modification seems to be singability: schnarchen would present even the most skillful singer with a problem, particularly to Schubert's 'pseudo-lullaby' music.

- The lines Je nun, sie haben ihr Theil genossen, / Und hoffen, was sie noch übrig ließen, / Doch wieder zu finden auf ihren Kissen, 'ah well, they have enjoyed their part and they hope that everything [that remains undreamed] will be found again on their pillows' require careful reading to extract their meaning. We can paraphrase as follows: the sleepers have enjoyed their dreams and they hope that they will be able to find what they left out from them the next time they go to sleep.

- The barking dog theme was introduced in poem 1, 'Gute Nacht' in Schubert's first section. It symbolises the narrator's rejection by the human society around him. Dogs guard the houses of the propertied class. In addition we now have rattling chains.

- In contrast with the dreaming villagers, the narrator has had enough of dreaming. In this context we may think back to poem 11, 'Frühlingstraum', in the first section, in which he dreamed of the life with his beloved he used to have – or might still have, for that matter. By now, in the current poem, he has come to realise that his dreams will always be unfulfilled.

- The narrator shows us his alienation from other people, an idea which we have already met in poem 12, 'Einsamkeit'.

- The phrase je nun is an idiomatic expression of resignation. It can be translated quite accurately by the modern use of the word 'whatever' in the meaning of 'who cares? It doesn't matter'. It is a remarkable expression to find in a German poem of this date. Müller's contemporaries would have been struck to find it here.[1]

18 Der stürmische Morgen (Wie hat der Sturm zerrissen…).

How the storm has torn the grey dress of the sky apart! The scraps of clouds flutter around in a weak fight. And tongues of red flame shoot between them. That's what I call a morning, matching my mood! My heart sees its own image painted in the sky – it is nothing other than the winter, the winter cold and tempestuous.

Notes

- There is no specific narrative place or time in this poem.

- I take the rothe Feuerflammen, 'tongues of red flame' to be lightning, but it could be just morning light penetrating the clouds ('red sky at morning, shepherd's warning'). It doesn't really matter.

19 Täuschung (Ein Licht tanzt freundlich vor mir her…).

A light dances seductively in front of me. I follow it hither and thither. I follow it gladly and note how it lures the wanderer. Oh, anyone who is as miserable as I am gives in happily to the bright trick that behind ice and night and misery and dread hints at a bright, warm house with a loving soul inside – gain is only an illusion for me.

Notes

- There is no specific narrative place, the time is still winter.

- Poem 9, 'Das Irrlicht' in section one shows a will o' the wisp leading the wanderer into a difficult terrain, but he is not deceived. The will o' the wisp in the current poem does not use the same symbolism or metaphor. The traveller interprets this will o' the wisp as being the lights from a house, in his imagination a friendly home with a nice girl inside.

- He knows this is an illusion, but for someone as miserable as he is it is a welcome one.

- The concluding line of the poem Nur Täuschung ist für mich Gewinn! is often mistranslated and misinterpreted (e.g. 'only deception is a gain for me'), a statement which is positioned somewhere on a scale between meaningless and absurd. In fact, the syntax of this line runs 'backwards' to facilitate rhyming drin with Gewinn. The meaning is easier to grasp if we take a more conventional word order: Für mich ist Gewinn nur Täuschung! 'For me gain/benefit is just an illusion', that is, there is no hope for me any longer and no reason to hope.

20 Der Wegweiser (Was vermeid’ ich denn die Wege…).

Why do I avoid the paths that other travellers take? Why do I look for hidden tracks through snowy mountain rocks? I haven't done anything for which I need to avoid people – what foolish desire drives me into the wilderness? Signposts stand on the roads, pointing to the towns and I wander endlessly, without rest and seeking rest. I see a signpost standing fixed in my gaze; I must follow a road from which no one has ever come back.

Notes

- The narrator is travelling through open country (without signposts). Snowy mountains imply that the time of year is winter.

- In the first two verses of the poem the narrator reveals a new aspect of his alienation from society: not just that he is rejected by others but that he himself avoids all contact with other people. We learned in the previous poem that all hope of improvement in his situation is illusory. He may let himself fall momentarily for the deception of the will o' the wisp but he knows in his heart that it is and always will be just an illusion. He himself describes his aversion to other people as a thörichtes Verlangen, a 'foolish desire'.

- I rendered Müller's versteckte Stege as 'hidden tracks', which does not really do justice to this very telling phrase. A Steg meant some kind of flimsy bridge over (or wooden walkway alongside) a mountain chasm (the narrator is currently in snow-covered rocky mountains). Such constructions were not for the faint hearted, usually quite wobbly and built by unknown hand. Schubert fans may think back to Goethe's formulation in the Lied 'Nähe des Geliebten', D 162b, in which the woman imagines her absent lover: In tiefer Nacht, wenn auf dem schmalen Stege / Der Wandrer bebt. 'In deep night, when the traveller shakes on the narrow walkway'. Goethe had personal experience of such frights on his journey into the Swiss Alps in 1775, which he recounted much later in his autobiography Dichtung und Wahrheit.[2]He did not have a good head for heights: as a young man he forced himself to ascend the spire of Strasburg Cathedral in the hope of curing himself of the problem.

- Müller uses the phrase Habe ja doch nichts begangen, / Daß ich Menschen sollte scheun, 'I have done nothing for which I would need to avoid people'. The verb begangen implies committing a crime or doing something socially reprehensible, something that would make you an outlaw from normal society.

- The third verse describes the signposts used by 'normal' people. Signposts on public roads that point to towns where others live. They are indicators of the social network that the narrator rejects and which rejects him, too. The fourth verse describes the grim signpost that the narrator sees, his personal signpost, one that points only along the road to death.

- The third verse also masterfully and laconically describes the parodox behind his ceaseless travelling: 'without rest and in search of rest'.

21 Das Wirtshaus (Auf einen Todtenacker…).

My path has taken me to a burial ground. I will end up here, I thought to myself. Your green wreaths could very well be the signs which invite tired travellers into the cool inn. Are all the rooms in this inn occupied? I am weary, ready to drop, and mortally wounded. O, pitiless tavern, are you really refusing me [accommodation]? Then onwards, ever onwards, my faithful staff!

Notes

- The narrative place is a cemetery; the time is unspecific.

- This poem is built around the metaphor of the inn, or guesthouse, as a cemetery, a place of death and repose.

- The inn also is a part of the wanderer motif running throughout the cycle. The inn should be a place of rest and refreshment for weary travellers. The metaphor of arriving at the inn, a tired wanderer, 'weary, ready to drop', but being refused entry and thus forced to continue the journey without rest or respite is a powerful one. Not only rejected by his beloved, her family and human society, he is now even rejected by the inn/cemetery. For him, death is not an available solution.

An aside: the 'death paradox' theme, poems 14-23

Being forced to continue this miserable journey is the resolution to what we might call the 'death paradox' in the Winterreise. The death paradox is the hope for an early release from misery through death, combined with the inability, because of the sinfulness of suicide, to put an end to that life. [3] The innate misery that the narrator feels is compounded by the horror he feels when he realises that this suffering may go on for a long time until his physical life ends and he is finally released.

Let's follow the development of the death paradox so far. In the first section, poems 1-12, death is only alluded to in one poem and mentioned directly only in one other, whereas in the second section, poems 13-24, the death paradox becomes a major theme in the cycle.

- In Section I, poem 5, 'Der Lindenbaum', the peaceful death that is alluded to twice by Hier findst du deine Ruh'! and Du fändest Ruhe dort! is firmly rejected. The narrator sets off against all resistance – the wind blowing in his face, his hat flying off. He seems to be made of sterner stuff than the soppy, lovelorn miller.

- In Section I, poem 9, 'Das Irrlicht', the theme of death is introduced as being the ultimate end of the narrator's misery. Jeder Strom wird's Meer gewinnen, / Jedes Leiden auch ein Grab. 'Every stream gains the sea, every suffering ends in a grave.' We note here that death is not simply the end of life, it is the inevitable end to suffering. The narrator's recognition of his mortal end is formulated and is to be understood as a passive death wish.

- In Section II, poem 14, 'Der greise Kopf', the narrator is longing for death, having realised how young he still is despite his pain and just how far off that death might be: Daß mir's vor meiner Jugend graut – / Wie weit noch bis zur Bahre!, 'My youthfulness is a shock. How long I will have to wait for my funeral bier!'. Death cannot come soon enough for him, but, because of the sinfulness of suicide, he cannot bring that moment forward. Realising how young he still is, he realises with horror how long he may have to wait for release. The inevitable path to the grave that he saw in poem 9 'Das Irrlicht', might be a very long one.

- In poem 15, 'Die Krähe', the narrator seems to have changed his mind about his life expectancy. He tells the crow that he will not have to wait long to be able to dine off his corpse: Nun, es wird nicht weit mehr gehn / An dem Wanderstabe., 'Well, there is not much further to go with my [wander-]staff.'

- In poem 20, 'Der Wegweiser' the narrator sees death as the only outcome for him: Eine Straße muß ich gehen, Die noch Keiner ging zurück., 'I must follow a road from which no one has ever come back.' Other signs point to human life and habitations; his sign points to his death, the hint being that death will come soon, almost as the next stop on his journey. There can be no detours to follow the other signposts back to human life.

- Now, in poem 21, 'Das Wirtshaus' we find the final resolution of the paradox. His recent hopes in poem 15 and poem 20 are now brutally dashed. His desire for death could not be made clearer: Bin matt zum Niedersinken / Und tödtlich schwer verletzt., 'I am weary, ready to drop, and mortally wounded.' The place of the dead is full up, he will have to wait his turn. He accepts the suicide ban and accepts that his fate will be to keep going until a time when the moment finally comes. Nun weiter denn, nur weiter, / Mein treuer Wanderstab!, 'Then onwards, ever onwards, my faithful staff!'

- If we look ahead to poem 23, 'Die Nebensonnen', we find there that the narrator confirms his miserable state and confirms his acceptance of the resolution of the death paradox that took place here in 'Das Wirtshaus': Im Dunkel wird mir wohler sein. 'I will feel better in the dark'. Not a conditional, a simple future sentence.

22 Muth! (Fliegt der Schnee mir in’s Gesicht…).

When the snow blows in my face I just shake it off. When my heart speaks in my breast, I just sing loud and cheerfully. I don't hear what it is saying to me, I don't have any ears. I don't feel what it is complaining about, complaining is for fools. Cheerfully into the world, against wind and weather. If no god wants to be on Earth, we ourselves have to be the gods.

Notes

- There is no specific narrative place but the time is winter.

- Why is this poem in Die Winterreise? There is nothing about it that matches any theme or mood in the rest of the cycle.

- It is possible to argue that the title 'Courage' and the talk of not listening to the heart expresses a possible resolution of the narrator's depression. A number of the previous poems in the cycle have been based around the narrator's dialogues with his heart, which would make this poem a completely mindless rejection of everything we have established so far.

- The spirit of the poem is much closer to one of Müller's many drinking songs and it is revealing that Schubert set it to an appropriate tune. It really is just a drinking or marching song. It is possible to argue that the narrator has put his introspection behind him and given himself over to mindless carousing. But, in the context of the cycle as a whole, such an argument does not work: this sudden epiphany pops up unheralded almost at the end of the cycle, after the 'death paradox' group and with 'Die Nebensonnen' and 'Der Leiermann' still to come. The text and music of this piece conspire to wreck the mood at the conclusion of this masterly song cycle.

- Even the logic of the argument has all the drunken incoherence of a drinking song: 'If no god wants to be on Earth, we ourselves have to be the gods.' How on Earth can this poem be followed by 'Der Leiermann'?

- The solution: never perform and never listen to this song in the context of Die Winterreise. Why did Müller include this poem and why did Schubert, with his fine antennae, set it? I can only assume that reaching a 'nice round number' – as Müller put it in his epilogue to Die schöne Müllerin – had a mistaken importance for him and for Schubert. One of Schubert's notable characteristics as a composer was the remarkable 'finishedness' of his work, particularly the Lieder. His manuscript scores are usually remarkably clean: it seems he was capable of working his music out thoroughly in his brain before writing it down. There may have been preliminary notes and fragments but we have very little evidence of these. In contrast Schubert revisited Die Winterreise during the little time that was left to him. He was even making changes to the cycle on his deathbed. Our futile hope is therefore that, had Schubert lived, he would have taken an axe to some of the elements of the cycle. But he was not granted that time and the axe never fell.

23 Die Nebensonnen (Drei Sonnen sah ich am Himmel steh’n…).

I saw three suns in the sky and watched them long and fixedly; They too stayed fixed, as though they could not get away from me. Oh, you are not my suns! Go and stare in someone else's face. Yes, recently I too had three: now the best two have set. Now let the third one set after them! I'll feel better in the dark.

Notes

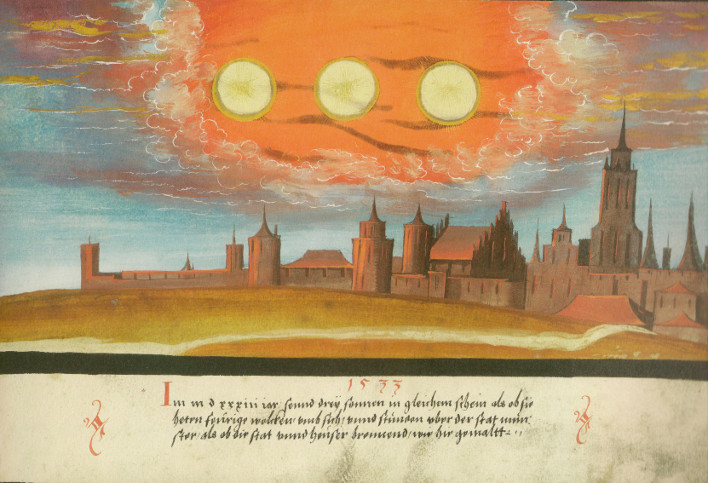

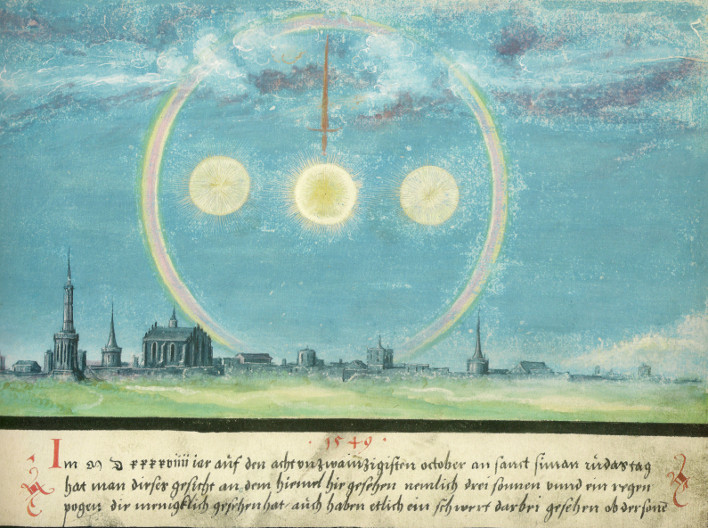

Three examples of portents in the sky involving 'Nebensonnen' taken from the Augsburger Wunderzeichenbuch (c. 1552), source Wikimedia

- There is no specific place for the narrative, but the time is winter.

- The metaphor that Müller has built around this phenomenon is difficult to decipher. Proof of this obscurity is provided by the number of contradictory explications of the metaphor that have been supplied by different commentators. The conclusion has to be that we have no reliable idea what Müller is talking about here. I cannot claim that I have any better insight, either, so here is some speculation that will have to do until the time when someone finds some credible evidence for a particular interpretation.

- In recent years it has become a received opinion amongst commentators that the title alerts us to the meteorological phenomenon called by that name in German ('sun dogs' in English). In a cold winter, ice crystals in the atmosphere can cause a low sun to appear to have a smaller companion on either side. The appearance of the phenomenon belongs to the season of a winter journey.

- A number of German authors from around that period, among them Goethe, mention seeing the phenomenon. The illustrations shown above from the 'Augsburg Illustrated Book of Miracles' demonstrate that in earlier, less enlightened centuries at least the appearance of multiple suns in the sky was not just regarded as a meteorological phenomenon.

- In the context of the Christian tradition in the West any mention of the number three evokes Biblical allusions from which, somewhat appropriately in the circumstances, we can select three major ones: the Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Ghost; the three of the crucifixion (Jesus and two robbers); the three 'theological virtues', faith, hope and love (a.k.a. 'charity'). It is difficult to see how the first two of these could apply in any way to Müller's metaphor of the three suns. The third, however, is a more promising explanation, since there is a contemporary tradition that the three 'suns' represent the three theological virtues.

- In particular, Christoph August Tiedge (1752-1841), like Müller a writer from northeast Germany, explicitly associated the three 'suns' of the weather phenomenon with the three virtues:

Kam – um an uns den Himmel zu verpfänden – / Das Göttliche zu uns herab, / Und strahlte – daß der Mensch sich selbst getreuer bliebe – / Der Tugend sanften Wiederschein, / Wie Nebensonnen, in die Triebe / Des dämmernden Gefühls hinein.[4]

'The divine came down to us to reveal Heaven and shone (that humans themselves remained more faithful) the gentle image of the virtues, like sun dogs, into the turmoil of decaying feelings.' Tiedge and Müller were known to each other, both had their popularity in their time but both faded into obscurity after their repective deaths. - The Bible, 1 Corinthians 13:13, tells us that 'the greatest of these is love', implying that this would be the central, real, sun. The two suns at the side would represent faith and hope. In Müller's poem, these virtues were not the narrator's: these three suns did not belong to him. The statement that they seem to be fixed on him, as if they couldn't go away, is a puzzle to me.

- It might very well be that Müller is alluding to Tiedge's statement, the 'gentle image of the [three] virtues' that shine 'into the turmoil of decaying feelings', but there is no direct evidence in the text for this. Here Müller, a hundred years before Modernist poets would expect us to be able to see inside their heads in order to decipher their products, has left us in the dark he wishes upon himself.

- The narrator himself used to have three suns, but two of these, 'the best ones', have gone dark. Can we assume that the 'side suns', faith and hope would be the first to go? In poem 16, 'Letzte Hoffnung', the narrator spoke of losing all hope. We have not been told explicitly of a loss of faith, but we might assume that this has also gone. All that is left is 'charity' the love of God and neighbours. When this is extinguished he is in the dark.

- This explanation does not really satisfy. A better interpretation might be that the narrator has certainly lost hope, we have been told that, but we also note that his love of his fellow man is now also non-existent, as expressed, for example, only a little before in poem 20, 'Der Wegweiser', Was vermeid’ ich denn die Wege…, 'Why do I avoid the paths that other travellers take? Why do I look for hidden tracks through snowy mountain rocks? I haven't done anything for which I need to avoid people – what foolish desire drives me into the wilderness?' In practice, it would make more sense to assume that he has lost both hope and love and that faith is the only thing he has left. It would be more comfortable for him if that went as well and his world became completely dark. This last thought may be the precursor to overcoming the prohibition on suicide.

24 Der Leiermann (Drüben hinterm Dorfe…).

Over there behind the village stands a hurdy-gurdy man. With stiff fingers he turns [out a tune] as best he can. Barefoot on the ice he rocks to and fro and his small [begging-]bowl always stays empty. No one wants to listen to him, no one looks at him; And the dogs growl around the old man. And he lets it all happen, however it may, turns the handle and his hurdy-gurdy is never silent. Strange old man, am I to go with you? Do you want to accompany my songs on your hurdy-gurdy?

Georges de La Tour (1593-1652), The Blind Hurdy-Gurdy Player, (1610-1630) one of a number of such portraits by or attributed to de La Tour. Seems rather too well-turned out to be Müller's beggar.

Notes

- The place is a village, the time is winter.

- This poem is such an astonishing literary performance of such complexity that, as we would when climbing a mountain, we have to begin our analysis with prosaic details, simply putting one step in front of the other as it were. Schubert's music rose to the occasion magnificently, so that, should we seek a monument for the Müller-Schubert partnership this poem is unarguably it.

- We note firstly that we are back in the depths of winter. We also note that the hurdy-gurdy player's location is 'over there, behind the village', a place of no import at all, away from the roads and the entrance to the village. This location underlines the social isolation of the beggar: were he in the centre of the village or near the main entrance we might reasonably assume he would be driven out.

- The old man is described as wunderlich, meaning 'strange', 'magical' or 'miraculous', the same word that was used in poem 15, 'Die Krähe', to characterise the crow that followed the narrator from the town on his journey: wunderliches Tier, 'strange creature'. Modern youth might say 'weird' or 'spooky'. The crow and the hurdy-gurdy man both have a symbolic, other-worldly aura for the narrator.

- The old man is clearly not playing the hurdy-gurdy for fun. We are told of his small begging bowl that never fills. Living in our comfortable modern age we forget, if we ever knew, how widespread begging was in Europe until quite recently. For Müller and Schubert, the hurdy-gurdy man was an everyday image. The begging hurdy-gurdy man is the visible embodiment of some personal tragedy: old age without a family to support him; illness and injury (beggars were frequently wounded ex-soldiers). Whatever it is that has brought our hurdy-gurdy man to this pass, he finds himself in the dying and irretrievable final phase of the trajectory of his life, just as the blind begger we discussed in Friant's painting 'La Toussaint' is portrayed: his back to the cemetery wall, only one step left to him. The beggar has no future and hardly any present: Und sein kleiner Teller / Bleibt ihm immer leer, 'and his small [begging-]bowl always stays empty'. When we discussed Friant's wonderful-terrible painting we also noticed the studied lack of eye contact between the well-to-do and the beggar (even though he is blind and cannot see them). Here, in 'Der Leiermann' we read that not only does no one want to listen to him, everyone avoids looking at him.

- The beggar and the narrator of the poem have much in common. They are both social outcasts, kept at a distance from others by growling dogs (a theme that started in poem 1 'Gute Nacht', re-emerged in poem 17, 'Im Dorfe' and now sees the beggar surrounded by them). Their rejection by society is total and they are both outcasts. They have both reached a state of final hopelessness and are united in the comradeship of despair.

- The two also share that universal characteristic of depression: apathy. Und er läßt es gehen / Alles, wie es will, 'And he lets it all happen, however it may', (idiomatically: he just lets it wash over him, like water off a duck's back) – the same 'who cares?' resignation we saw expressed by the phrase je nun, 'ah well' or 'whatever' in poem 17, 'Im Dorfe'.

- The beggar and the narrator of the poem also share their pointless obsessions. The beggar just keeps cranking his hurdy-gurdy even though no one wants to hear him or gives him any money: Dreht, und seine Leier / Steht ihm nimmer still, 'turns the handle and his hurdy-gurdy is never silent'. Similarly, at least up to now, the narrator has kept on with his obsessive wandering, constated for example in poem 20, 'Der Wegweiser': Und ich wandre sonder Maßen, Ohne Ruh', und suche Ruh' 'I wander endlessly, without rest and seeking rest'. What would happen if either of them stopped?

- Finally, the common ground between them is underlined when the narrator addresses the beggar using the intimate form du: Soll ich mit dir gehn? ... Deine Leier drehn? In German ears that expresses immediately a comradeship, a fellowship, without any social distinction. The use of du here is not a lack of respect as it would be if said to a bourgeois stranger on the road or in the town but a mark of social bonding. We meet a similar effect in Müller's work when conversing with streams and trees, particularly in combination with the title Geselle.

- As if we didn't have enough puzzles, the final verse offers us one further conundrum. Wunderlicher Alter, Soll ich mit dir gehn?, 'Strange old man, am I to go with you?'. I have translated the German modal verb 'Soll' with the English construction 'am I to do something', not 'shall', which is the usual translation. The reason for this is that 'shall' has been much reduced in the last hundred years, losing much of its modal force. To the ear of a modern speaker of English 'shall I go with you?' appears to be just a neutral, rather polite question. A fairy Godmother can still say 'You shall go to the ball, Cinders' and be understood; she could also say with exactly equivalent meaning 'You are to go to the ball, Cinders', but 'shall' in most of its other manifestations is now but a shadow of the word it once was. The German phrase implies some divine providence: 'so this is what is meant to be'.

- Similarly, Willst zu meinen Liedern / Deine Leier drehn?, 'Do you want to accompany my songs on your hurdy-gurdy?' has been translated here in a strict and pedantic way. The usual English translation, seen everywhere, is something like 'Will you play your Hurdy-gurdy to my songs'. Such a translation makes it sound as though the the narrator is asking the beggar to accompany his songs, which is not the case at all and leads to a serious misunderstanding. German wollen has strictly the English meaning 'to want to'. The narrator is therefore not asking the begger to play his hurdy-gurdy to his poems, but asking him whether he wants to play them – a big difference.

- We were relieved to note that Die Winterreise, unlike Die schöne Müllerin, has no prologue and epilogue. Nevertheless, a strange thing has happened in the last verse of 'Der Leiermann': the poet speaks of his songs. This is a remarkable change of narrative focus. Up until now we have had no poet and no songs, simply a collection of poems with a first-person narrator. Suddenly, the person speaking to the beggar is now the poet who has created the songs – presumably the poems we have been reading in the cycle. How can this be?

- It means that the observer describing the encounter with the beggar is not the protagonist of all the other poems. The person meeting the beggar is Wilhelm Müller, the poet himself. The narrator is not known to us as a poet: he has always been the protagonist in a poem, not its author. In consequence, 'Der Leiermann', that triumphal conclusion of Die Winterreise, is not really part of it. It is an epilogue. In this respect we note that, whatever else Müller rearranged in the cycle, 'Der Leiermann' was always the last poem in the series. Is the hurdy-gurdy player the final incarnation of the narrator, the endpoint of that long wandering through depression and social rejection? Is this his own epilogue?

You ask me: 'Yes, but what does it all mean, 'Der Leiermann'?' I answer: 'I have no idea.' Great art – and the Müller/Schubert 'Der Leiermann' is art of the very highest level, not just astonishingly modern but timeless – great art speaks a language that we can feel but barely understand, let alone parse. In German, Friedrich Hölderlin attained such peaks of symbolic meaning. The closest parallel in English that comes to my mind is W. H. Auden, whose work, influenced by Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud, was at its best a fine encapsulation of symbolic psychoanalysis. Like Hölderlin, but unlike Müller, Auden was also a master of metrical structure:

The bolt is sliding in its groove;

Outside the window is the black remov-

-er's van:

And now with sudden swift emergence

Come the hooded women, the hump-backed surgeons

And the Scissor Man.[5]

I am not carrying a flag for Auden here: many of the greatest poets in English and German at their greatest moments achieved a communication that transcended the normal operation of language and defy the probing scalpel of analysis. I could provide many examples. But this article is about Wilhelm Müller and Die Winterreise, in which he achieved some great poetic heights that transcended almost anything else he ever did and which in turn were raised even higher by Franz Schubert. Can anyone be surprised at Schubert's excitement when Müller's Die Winterreise fell into his hands?

Conclusion, Chapter 3, poems 13-24

Let us summarise the narrative line that we have followed through the poems of the second section. In 'Die Post' the narrator hears a posthorn and asks his heart why it has become so excited, even though it knows there will be no letters for it. Does it want to return to the town where the beloved lives? In 'Der greise Kopf' he realises how far off the longed-for death is. In 'Die Krähe' he speaks to a crow that has followed him since he left the town; he tells the crow that his death will come soon. In 'Letzte Hoffnung' he associates his fate with leaves on the trees. In 'Im Dorfe' he describes his isolation from the people in a village he passes through at night. In 'Der stürmische Morgen' he sees the fiery turmoil of the stormy sky as a metaphor for his heart. In 'Täuschung' he realises there is no hope for an improvement in his situation. In 'Der Wegweiser' he realises he is doomed to wander 'endlessly', following a path that leads to death. In 'Das Wirtshaus' he is not granted the early death he desires so much. In 'Muth!' he slaps his chest and marches on cheerfully into the world. In 'Die Nebensonnen' he sees a weather phenomenon that creates the illusion of three suns; the three suns are not for him, two of his have already been quenched and he is looking forward to the darkens when the third sun sets. In 'Der Leiermann' the poet Müller meets a beggar with a hurdy-gurdy outside a village.

Reading this, our conclusion must be that in the second section of Die Winterreise there is no narrative line. If we are given any idea of place or time it is just sketchy. There is a flimsy connection with what went before in the first section in only two poems: 'Die Post', where the post-coach comes from the town where the beloved lives and 'Die Krähe', in which the narrator has been accompanied since leaving the town by a crow, presumably one of those that helped drive him out during his exit.

If there is a structure in the second section it is not narrative but rather episodic and thematic. In our notes to poem 21, 'Das Wirtshaus' we noted the 'death paradox' theme: the helpless waiting for death without the possibilty of release in suicide. The development of this theme means that there are eight poems, from poem 14, 'Der greise Kopf' to poem 21, 'Das Wirtshaus', that hang together as a unit, a unit through which the theme of the death paradox is introduced, developed and resolved. It is telling that Schubert kept this block together in his re-ordering of the second section, as did Müller when he rearranged the entire cycle for publication in his 'Waldhornist' collection.

Themes and sequence in section II of Die Winterreise

Three of the poems in the second section are difficult to reconcile with the overall mood of the cycle and the thematic structures in it:

- Poem 13, 'Die Post', is not only out of place for its bounding cheerfulness but also for its confusing sense of location. The narrator (and his heart) already seem to have separated themselves from the girl and the town. This is the only poem in the second section that mentions the loved one. As far as section two is concerned, she has ceased to exist as a personage. In my opinion this poem should not be sung as part of the cycle but rather as a standalone poem that can survive outside the context of the whole.

- Poem 22, 'Muth!', apart from being a dialogue between the narrator and his heart has no connection with anything else in the entire cycle. Its tone and mood is entirely dissonant. In my opinion this poem should not be sung as part of the cycle. If you like drinking songs it can be performed as such on its own. In his 'Waldhornist' re-ordering this poem is the last poem of the cycle, if we consider poem 24, 'Der Leiermann' to be an epilogue. A bizarre decision.

- Poem 23, 'Die Nebensonnen', fits in with the mood of the second section of the cycle, but because of its obscurity is difficult to position in the context of the whole. If we have no real idea what it is about, how do we know where to put it? It contributes puzzlement, but otherwise does no harm and could be left in. However, in Schubert's sequence, 'Die Nebensonnen' is the last poem of the cycle, if we consider poem 24, 'Der Leiermann' to be an epilogue. As such it is a harmless, if confusing conclusion. In his 'Waldhornist' re-ordering Müller put the poem after poem 10, 'Rast', in which the narrator is in the charcoal burner's hut, and before poem 11, 'Frühlingstraum' and poem 12, 'Einsamkeit'. We can only say: Schubert was right.

Structural comparison of text editions of Die Winterreise. Left, the collection that appeared in Urania Taschenbuch auf das Jahr 1823; Middle, the collection chosen by Schubert; Right, the collection that appeared in Sieben und siebzig Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines reisenden Waldhornisten, 1824, vol. 2.

We shouldn't throw Poem 13, 'Die Post' and Poem 22, 'Muth!' away: as late Schubert works they would fit happily into the rag-bag collection that is Schwanengesang, leaving behind a much more coherent Die Winterreise.

References

-

^

Of je nun Rolf Vollmann says: Da wird ein ganz irritierendes Einverstandensein mit allem deutlich. 'Je nun', heißt es im Gedicht 'Im Dorfe': ein platter, völlig prosaische Ausdruck, wie dann ja überhaupt diese Strophe einen beinahe ganz 'ungedichteten' Eindruck macht. 'A disconcerting tolerance of everything becomes clear. 'Whatever', we read in the poem 'Im Dorfe': an everyday, completely prosaic expression that gives this verse an almost 'unpoetic' feel.'

Wilhelm Müller, Franz Schubert, Die Schöne Müllerin, Die Winterreise, Nachwort: Rolf Vollmann, Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart, 2001. ISBN 978-3-15-018121-8, p. 81. - ^ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Dichtung und Wahrheit, Part IV, Book 18, Philipp Reclam, Stuttgart, 1991, pp. 790-802

- ^ The social/religious abhorrence of suicide was very real at this time. Goethe's novel Die Leiden des jungen Werther (1774) had been a bestselling sensation, despite – or because of – the widespread scandal it had caused with its depiction of the hero's suicide. The book was ineffectually censored in various places for most of the 19th century.

- ^ Christoph August Tiedge, Urania, Book 4, 'Unsterblichkeit' (Deutsche Nationalliteratur, Band 135, Stuttgart, S. 307-323.) Urania, Viertes Gesang, online text.

- ^ W. H. Auden, Collected Poems, Faber and Faber, 1976, 'The Witnesses' (1932), p. 73. NB: The name 'Scissor Man' is an example of Auden's allusive technique of psychological nightmare. In its dark context the expression alludes to the German Sensenmann, the 'Grim Reaper'.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!