Die Winterreise, Chapter 4

Richard Law, UTC 2015-12-31 16:14

The biographical background: Wilhelm Müller

We should be very wary of attempts to 'explain' a work of art by reference to its author's biography.

- If a work needs the study of further works to explain it, then it already has considerable defects. A modern example of this would be James Joyce's monumentally obscure 'novel' Finnegans Wake: a paragraph or two spent with a dozen open reference works and a study guide to hand can be amusing, a page tedious, the 628 pages of the Faber edition unthinkable – no amount of coffee drinking and biscuit eating will get me through that. However brilliant it is, the book can never repay the effort of reading it.

- Even worse: if we need to reach for the biography of its creator to 'understand' a work of art then one could argue that the work has failed completely. The American poet Ezra Pound assumed that his readers could see inside his head, that they had read the books and manuscripts he had read, met the people he had met and seen all the things he had seen. The task of explaining fleeting biographical moments is keeping scholars busy to this day – the normal reader is left baffled. Why bother?

- The biographies of artists are interpretations of their lives, which means that when we use them to interpret a work we are building an interpretation on the basis of another interpretation. William Shakespeare has the great good fortune that we barely know anything about his life, so we have been forced to look at his works as autonomous works of art, despite occasional hunts for 'Dark Ladies'. Shakespeare scholarship would be much poorer if the Bard had left behind a rich biographical documentation. We would still be trying to identify which of his acquaintences was the model for Hamlet.

- We even come across biographies of literary figures that interpret the subject's life in terms of some intepretation of the works, thus bringing us full circle to interpretations of interpretations of interpretations.

- This is not to say that the biographical background to a work of art isn't interesting – it is – but although this may put the work in an interesting context, it is rarely an explanation that allows us to understand the text better.

For all these reasons and many more that we don't need to go into here, on this blog we stick strictly to the text in front of us and leave the biographical elements to one side.

And yet…

With Wilhelm Müller we have this unresolved – never to be resolved – question: where on Earth did the poems of the Die Winterreise come from?

If we just consider the eighty-nine poems in Sieben und siebzig Gedichte aus den hinterlassenen Papieren eines Waldhornisten, Zweites Bändchen which contains Die Winterreise we have:

31 Tafellieder für Liedertafeln ('Table songs for male choirs').

12 Ländliche Lieder ('Rural songs').

6 Wanderlieder ('Songs of travel').

16 Devisen zu Bonbons, ('Sayings for bonbons').

After the thirty-one drinking songs come the twenty-four dreary poems of Die Winterreise. How is this to be understood? What thematic organization of a book of verse can be seen here? Waldhornist 2 is like a bucolic landscape painting by Caspar Friedrich David, with all its trees and flowers, maids and yokels and even a sing-song going on in the pub. In the middle foreground we see a black pit painted by Hieronymous Bosch, full of souls in torment.

We have to ask some questions. After publishing Die Winterreise in his Waldhornist 2 collection in the way he did, can we believe that Müller was in any way serious about the poems of Die Winterreise? If the collection is so brilliant, so painful and personal, why did he just dump it among all his drinking songs? If there is a studied collection there, why did he publish it in unconnected parts? Was it all just fashionable role-play and irony? Are we making the mistake of treating Müller's Die Winterreise with a pious respect that he himself did not feel for it?

We immediately run into trouble when we try and answer these questions using biographical sources. Müller was long considered a D-list writer in German literature. There is no disagreement that, if it hadn't been for Franz Schubert, Müller would barely be known nowadays. His star faded quite quickly and obscurity started to overtake him even before his death. As a result, he has had poor biographers. Müller's long entry in the Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (1885), was written by his son in a spirit of filial piety. It tells us nothing of the passions of his life he experienced before he married – not a single name. The brief entry in the Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (1997) is worse, since by the time this entry was written, Müller's importance as anything other than the author of the Schubert song-cycles had faded completely. He is simply no longer worth the paper. It is true that these two 'official' German biographies, the ADB and the NDB, always tend to be more like a very respectful and factual C.V. than a biography, but later, more conventional works just fill in the many gaps with speculation.

Muller was born into a respectable but poor family in Dessau, his father a master tailor, his mother the daughter of a locksmith – the lower orders of the society of the time. His parents provided him with a good educational start. After the death of his mother (in 1808) his father married the well-to-do widow of a master butcher, who brought the money into the family that paid for his university education. He went to university in Berlin (in 1812). He was a heavy drinking, socially involved student, whose intellectual pursuits seem to have been more political than academic.

Caught up in the wave of anti-Napoleonic sentiment in Germany he joined a volunteer brigade of the Prussian army (in early 1813). His studies had not lasted long. In 1813 he took part in a number of battles and was promoted to the rank of leutenant, but by autumn of that year his battling days were over and he ended up in various staff positions in Prague and (in 1814) Brussels. The remainder of this part of his life disappears into the mists of time. There was a woman involved, we think her name was Therese. He left the army in November 1814, eighteen months after he had joined, presumably with a dishonourable discharge, since it seems that he never mentioned his service after that. Whether Therese was the cause of his departure and who rejected whom we do not know.

Müller set off from Brussels back to the family home in Dessau. Some think that this journey and his lost love, Therese, were the genesis of Die Winterreise, that he wrote about ten years later. Müller started keeping a diary in late 1815 from his 21st birthday onwards. From allusions in the diary something dramatic seems to have happened in 1814 that involved Müller and even his own family, but we know nothing more about it. Looking back on that year, Müller adds a note to his diary: he managed to survive everything and it now seems to him that during that year he went 'either from a child to an old man or from an old man to a child'. Not quite what was meant in poem 14, 'Der greise Kopf' but an interesting echo, nonetheless.

Out of the frying pan into the fire. In Berlin, even before he had gone off to war, he had got to know the painter Wilhelm Hensel and through him his sister Luise. There are times when everyone, man or woman, needs a friend who will say to them: 'Don't do it'. It seems that Müller didn't have anyone like this to tell him not to get involved with Luise. She was intensely religious, even converting from intense Protestant pietism to intense Catholic piety. He fell in love with her and spent much time trying to suppress his baser instincts and live up to her fanatical, otherworldly religious ideals. Many men in the Berlin circles she frequented fell in love with her, all were rejected. She left Berlin in 1819 and took a vow of chastity in 1820.

Left: Luise Hensel (1798-1876), as drawn by her brother Wilhelm. Right: Wilhelm Müller (1794-1827) as a young man.

Müller worked on his career in Berlin. In 1816 through the Hensels he came into contact with the salon around the daughter of the Prussian Minister Friedrich August von Stägemann, a circle that included many of the most notable names in the Berlin social and literary scene. We mentioned these gatherings briefly in our notes on Die Schöne Müllerin. The genesis of the 'mondrama' of Die schöne Müllerin is to be found in the plays, songs and poems that were performed in the von Stägemann circle. But knowing this really makes no difference to our understanding of that song-cycle.

In the same way, trying to untangle the passions and jealousies within the circle is pointless. Whether Luise in her chaste way preferred the dashing and brilliant Clemens Brentano to the mediocre Müller deepens our understanding of Die schöne Müllerin not a jot. We are told that when the play was performed at the Stägemann's salon, Müller played the miller and Brentano was – what else? – the hunter. In the same way, for our rejected narrator in Die Winterreise we can pick and mix events from Müller's biography ad libitum: his rejection(?) by Therese, the winter flight from Brussels to Dessau, his rejection by Luise, Brentano as the rich suitor. It doesn't matter. None of it does.

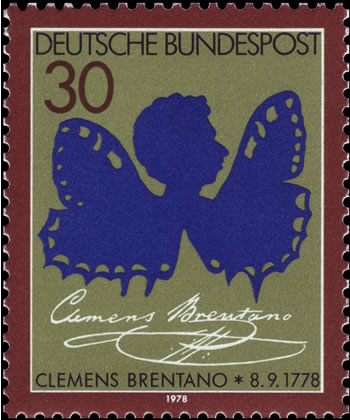

Left: Clemens Brentano (1778-1842). Right: The postage stamp produced in Germany in 1978 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Brentano's birth. It comtains the papercut silhouette of 'Brentano as a Butterfly' done by Luise Duttenhofer sometime before 1830. Like a butterfly, Brentano fluttered rapidly from one obsession to another, his life a series of unfinished studies and brief enthusiasms. Never mind. Brentano got the postage stamp and Müller was forgotten. In Waldhornist 2 Müller has a poem Amor, ein Schmetterlingsfänger, 'Love, a butterfly catcher', but if there is an allusion to Brentano it is very obscure.

In 1820, the year he published Waldhornist 1 (containing Die schöne Müllerin), he got engaged to Adelheid Basedow. They were married in 1821 (in May, of course) and a daughter and a son were born in 1822 and 1823 respectively, The marriage was happy, both children survived (unlike Müller's family, in which he had been the only survivor out of six children). In 1824, the year he published Waldhornist 2 (containing Die Winterreise), he was made a ministerial counsellor (Hofrat) and thus the tailor's son finally achieved his social standing.

During this apparently happy period – his marriage, his children, his career – he was writing Die Winterreise. Perhaps this song-cycle really is just persona and irony?

Müller the mimetic

We might risk an opinion about Müller that may shock: he was not an innovator, his work is largely mimetic.

His excellent grasp of English led him to Byron. He became the German mouthpiece of Byron's alignment with the fight for Greek independence from the Ottoman Türks that was one of the great political themes of the 1820s. So loud was his advocacy of the cause that he became known as Griechen-Müller, 'Greek Müller', an epithet which eclipsed all his other work as a Romantic poet. His publication of ten poems as Lieder der Griechen sold well, which prompted him, the eternal scribbler, to scribble more and then more of the same. 'Greek Müller' had never been to Greece, meaning that, in effect, his campaign was pure posturing. He picked up other people's ideas and passed them on.

Even in Die Winterreise we find bits that seem to come from other people's minds. Some of these 'allusions' we discussed in the notes on the individual poems. Tiedge's 'Nebensonnen', Eichendorff's suicidal miller, Brentano's icy heart melting into tears. One would be a coincidence; three are suggestive. A Ph.D. thesis awaits the drudge willing to spend a few years tracking down all Müller's borrowings. Perhaps I am being unfair to Müller – probably not for the first time, either.

In his other Romantic work he was also derivative, completely in tune with a time of yokels, maids and all the other frippery of the Romantic mind, picking up the images and symbols that others had created. After Müller's death Heinrich Heine praised him, but only as one who could write poetry that was more convincingly 'natural', that is, clunky and rustical, than the great 'people's poet', Ludwig Uhland – a characteristic and fine piece of Heine irony: unlike Uhland, Müller didn't need to try to hard to write rough poetry, it came naturally to him.[1]

Fans of Franz Schubert reading this need only compare Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart's poem 'Die Forelle' – the one which Franz Schubert turned into the magical song that kept C.F.D. Schubart's name alive just as he would keep Wilhelm Müller's name alive – with Müller's own 'Die Forelle'. There is no comparison: Müller's poem is just awful, trite, one-dimensional everyday pap, from a man who could not stop writing and never seemed to revise.[2] We are not surprised that many critics ask themselves: Did this man Müller really write Die Winterreise? Are we sure, really sure, that the poems are by him?

To which this critic then says: yes, he did write them, but perhaps, when we read them carefully and analytically, they are really not much better than his other poems.

References

- ^ Heinrich Heine, Die romantische Schule(1833), Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart, 1976(2002), UB-9831, Drittes Buch, p. 150. Online version.

- ^ Wilhelm Müller, 'Die Forelle', in Frühlingskranz aus dem Plauenschen Grunde bei Dresden in Lyrische Reisen und epigrammatische Spaziergänge, Leipzig, 1827. Online version.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!