For the greater glory of God: Benjamin Franklin

Richard Law, UTC 2016-05-01 07:47

In contrast, Carl Schubert's American near-contemporary Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), the model of Protestant culture held up as an example by Max Weber, believed that 'that the most acceptable Service of God is doing Good to Man'.[1]Franklin would have viewed Carl's spending as ineffectual, being without utility.

Franklin, a successful publisher and printer – in fact successful at almost everything to which he turned his hand – published a collection of his 'Poor Richard' aphorisms called Franklin's Way to Wealth, full of advice on the benefits of saving and frugality. Weber quotes extensively from Franklin's 'Advice to a young Tradesman' (1748). We have already quoted from some of Franklin's writings.

Whilst 'the Cannibals of Europe are going to eating one another again'[2] this time in the 'War of the Austrian Succession', Franklin was writing on wealth and its creation. Austria was maintaining a large standing army, ready for the next cannibalistic feast that would come soon, the 'Seven Years' War'. Whilst the feudal serfs who could do so went back to their bits of land for a few years and thought of their harvests and repairing the ravages of war, Franklin and his 'Young Tradesman' were considering how to improve the lot of mankind for the glory of God and make themselves rich while they were about it.

It is truly a manifesto for the Protestant Ethic, reproduced here in a slightly abridged form:

Remember that Time is Money. He that can earn Ten Shillings a Day by his Labour, and goes abroad, or sits idle one half of that Day, tho’ he spends but Sixpence during his Diversion or Idleness, ought not to reckon That the only Expence; he has really spent or rather thrown away Five Shillings besides.

Remember that Credit is Money. If a Man lets his Money lie in my Hands after it is due, he gives me the Interest, or so much as I can make of it during that Time.[…]

Remember that Money is of a prolific generating Nature. Money can beget Money, and its Offspring can beget more, and so on. […]

He that kills a breeding Sow, destroys all her Offspring to the thousandth Generation. He that murders a Crown, destroys all it might have produc’d, even Scores of Pounds. […]

Remember this Saying, That the good Paymaster is Lord of another Man’s Purse. He that is known to pay punctually and exactly to the Time he promises, may at any Time, and on any Occasion, raise all the Money his Friends can spare. […]

The Sound of your Hammer at Five in the Morning or Nine at Night, heard by a Creditor, makes him easy Six Months longer. But if he sees you at a Billiard Table, or hears your Voice in a Tavern, when you should be at Work, he sends for his Money the next Day. […]

Beware of thinking all your own that you possess, and of living accordingly. […] To prevent this, keep an exact Account for some Time of both your Expences and your Incomes. […]

In short, the Way to Wealth, if you desire it, is as plain as the Way to Market. It depends chiefly on two Words, Industry and Frugality; i.e. Waste neither Time nor Money, but make the best Use of both.[3]

If there is any doubt that this is just as much a religious programme as an economic programme we only need to consider Franklin's final paragraph, which we have already quoted:

He that gets all he can honestly, and saves all he gets (necessary Expences excepted) will certainly become Rich; If that Being who governs the World, to whom all should look for a Blessing on their honest Endeavours, doth not in his wise Providence otherwise determine.[4]

In his moral tracts Franklin is writing in the Biblical tradition of Proverbs, the' Sermon on the Mount' and Paul's Epistle to the Romans, the latter one of the cornerstones of Protestant – especially Dissenting – belief. He was writing for the widest possible audience and expressed himself in plain language and memorable aphorisms, many of which are still current to this day.

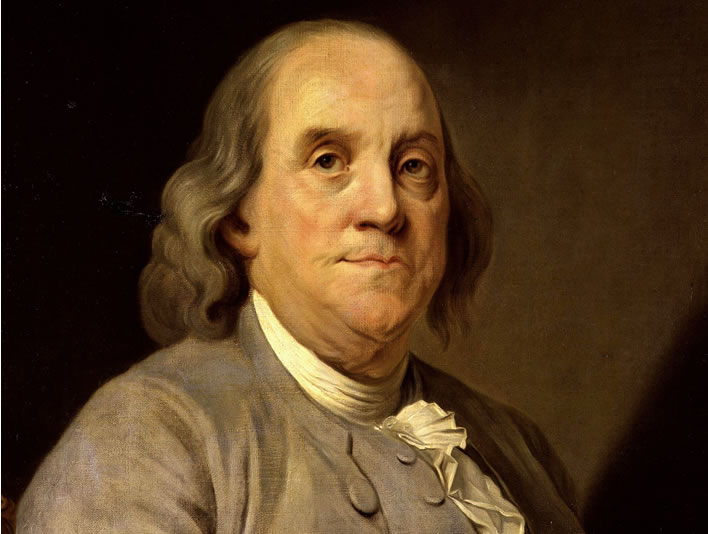

Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) by Joseph Duplessis (1725–1802), c. 1785. Image: National Portrait Gallery, Washington

Franklin and religion

Franklin avoided mumbo-jumbo all his life, particularly in religious matters. He subjected everything he read or heard to critical analysis. He had the spiritual self-confidence to reject whatever was 'unintelligible' to him. He did not need a church hierarchy to mediate ideas to him:

I had been religiously educated as a Presbyterian; and tho’ some of the Dogmas of that Persuasion, such as the Eternal Decrees of God, Election, Reprobation, &c.appear’d to me unintelligible, others doubtful, and I early absented myself from the Public Assemblies of the Sect, Sunday being my Studying-Day, I never was without some religious Principles;…[5]

Franklin is uninterested in religious obedience, which in itself is a remarkable contrast with the Catholic attitude, in which obedience is paramount. In Catholicism, extreme disobedience is one of the blackest of sins. Franklin draws a distinction between religious obedience (which, in his Protestant world is just a form of obedience to other humans) and moral obedience, which is obedience to God and the requirement to do good to man:

But [the Presbyterian Minister's] Discourses were chiefly either polemic Arguments, or Explications of the peculiar Doctrines of our Sect, and were all to me very dry, uninteresting and unedifying, since not a single moral Principle was inculcated or enforc’d, their Aim seeming to be rather to make us Presbyterians than good Citizens. At length he took for his Text that Verse of the 4th Chapter of Philippians, 'Finally, Brethren, Whatsoever Things are true, honest, just, pure, lovely, or of good report, if there be any virtue, or any praise, think on these Things'; and I imagin’d in a Sermon on such a Text, we could not miss of having some Morality: But he confin’d himself to five Points only as meant by the Apostle, viz. 1. Keeping holy the Sabbath Day. 2. Being diligent in Reading the Holy Scriptures. 3. Attending duly the Publick Worship. 4. Partaking of the Sacrament. 5. Paying a due Respect to God’s Ministers. These might be all good Things, but as they were not the kind of good Things that I expected from that Text, I despaired of ever meeting with them from any other, was disgusted, and attended his Preaching no more.[6]

His response to this problem was a characteristically Protestant response rather than a Catholic one. Can we imagine a Catholic response such as this? Such arrogant disobedience would ensure your eternal damnation:

I had some Years before compos’d a little Liturgy or Form of Prayer for my own private Use, viz, in 1728. entitled, Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion. I return’d to the Use of this, and went no more to the public Assemblies.[7]

Franklin and the 'calling'

It is from Franklin that we can also get examples that justify the importance that Max Weber placed on the word 'calling'. Writing in his Autobiography, Franklin quotes his father's repeated good advice to him:

My original habits of frugality continuing, and my father having, among his instructions to me when a boy, frequently repeated a proverb of Solomon, 'Seest thou a man diligent in his calling? he shall stand before kings; he shall not stand before mean men,'[8]

What is interesting here is not just that Franklin used the word 'calling' but that he – or possibly his father – is misquoting the biblical source, Proverbs 22:29, here in the King James version of 1611:

Seest thou a man diligent in his businesse? hee shall stand before kings, he shall not stand before meane men.

One of the Franklins, father or son, substituted 'calling' for 'business'. I know of no English bible translation before Franklin's time that uses 'calling' instead of 'business'. Even Luther, in his 1545 translation of Sprüche 22:29 has Geschäft, which completely and uncontroversially aligns with 'business' in the English versions:

Siehst du einen Mann behend [=tüchtig] in seinem Geschäft, der wird vor den Königen stehen und wird nicht stehen vor den Unedlen.

Some process in the father or the son's head, much deeper that a simple slip is at work here. The rest of Franklin's quotation is a completely accurate, word for word reproduction of the verse as it stands in the King James translation. The son tells us that his father 'frequently repeated' the verse from Proverbs, so either one or both are using a Bible source I don't know about at the moment – a translation that is exactly the same as the King James Bible except for that one word – or one or the other of them has substituted the word accidentally or deliberately. If the latter, it would seem to us now to be an interesting and unusual substition to use 'calling' instead of the much easier word 'business'.

But perhaps 'calling' was really the easier, more natural word for Franklin. For example, when he set up a headstone on his parents' grave some years after their death he had the following text inscribed:

Josiah Franklin / And Abiah his Wife / Lie here interred. / They lived lovingly together in Wedlock / Fifty-five Years. / Without an Estate or any gainful Employment, / By constant labour and Industry, / With God’s Blessing, / They maintained a large Family / Comfortably; / And brought up thirteen Children, / And seven Grand Children / Reputably. / From this Instance, Reader, / Be encouraged to Diligence in thy Calling, / And distrust not Providence. / He was a pious & prudent Man, / She a discreet and virtuous Woman. / Their youngest Son, / In filial Regard to their Memory, / Places this Stone. / J.F. born 1655—Died 1744. Aetat 89 / A.F. born 1667—died 1752 ——85[9]

The calling is more than an occupation, though. The word is not interchangeable with 'trade' for example:

He that hath a Trade hath an Estate, and He that hath a Calling hath an Office of Profit and Honour; but then the Trade must be worked at, and the Calling well followed, or neither the Estate, nor the Office, will enable us to pay our Taxes.[10]

Franklin's programme

Franklin also presents us with an example of the later Calvinistic (Presbyterianism is a direct descendent of Calvinism) love of systems for moral advancement that Max Weber had discussed. The 20-year-old had already drafted a Plan of Conduct containing four principles for himself.

let me, therefore, make some resolutions, and form some scheme of action, that, henceforth, I may live in all respects like a rational creature.[11]

Two years later he lays down a much more extensive moral panorama in his Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion. He gives over the whole of Part 9 of his Autobiography to a description of his quite astonishing moral bookkeeping system. He has by now conceived of 13 main precepts and implements them using a little book in which he documents his progress.

I determined to give a Week’s strict Attention to each of the Virtues successively. Thus in the first Week my great Guard was to avoid every the least Offence against Temperance, leaving the other Virtues to their ordinary Chance, only marking every Evening the Faults of the Day.

Thus if in the first Week I could keep my first Line marked T clear of Spots, I suppos’d the Habit of that Virtue so much strengthen’d and its opposite weaken’d, that I might venture extending my Attention to include the next, and for the following Week keep both Lines clear of Spots. Proceeding thus to the last, I could go thro’ a Course compleat in Thirteen Weeks, and four Courses in a Year.

And like him who having a Garden to weed, does not attempt to eradicate all the bad Herbs at once, which would exceed his Reach and his Strength, but works on one of the Beds at a time, and having accomplish’d the first proceeds to a Second; so I should have, (I hoped) the encouraging Pleasure of seeing on my Pages the Progress I made in Virtue, by clearing successively my Lines of their Spots, till in the End by a Number of Courses, I should be happy in viewing a clean Book after a thirteen Weeks daily Examination.[12]

References

- ^ Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography, Part 10 Yale University Library

- ^ A perceptive remark of Thomas Jefferson's in 1822 in 'Thomas Jefferson to John Adams', Letters, 1 June, 1822

- ^ Benjamin Franklin, 'Advice to a Young Tradesman', in The American Instructor: or Young Man's Best Companion, 1748. pp. 375-7.Yale University Library

- ^ Benjamin Franklin, 'Advice to a Young Tradesman', ibid.

- ^ Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography, Part 8 Yale University Library

- ^ ibid Yale University Library

- ^ ibid, Part 8 Yale University Library

- ^ ibid, Part 8 Yale University Library

- ^ ibid, Part 1, Yale University Library

- ^ Benjamin Franklin, Poor Richard Improved, 1758, p 326.Yale University Library

- ^ Benjamin Franklin, Plan of Conduct, 1726, p 99.Yale University Library

- ^ Benjamin Franklin, Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion, 1728, p. 101.Yale University Library

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!