The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

Richard Law, UTC 2016-05-01 07:40

The decline and fall of the Habsburg Empire

In 1700 the dominant political power in continental Europe was the Holy Roman Empire. It was a ragtag jumble of states and legal interdependencies that modern historians find as difficult to explain as once Joseph II did. Without lifting the stone too far and exposing all the wriggling things that are underneath it to unwelcome light, we only need to note here that the Empire had a core and a periphery.

That core we can call rather sloppily the 'Austrian Empire' or just the 'Habsburg Empire'. The periphery was made up of the fragmentary states that arose from the Peace of Westphalia, concluded in 1648 when Europe, scoured pitilessly for thirty years by all four of those pale horses, staggered exhausted into a complex peace. During that time the pale horses were even busier than usual, if we modishly take into account the 'Little Ice Age' that occurred during that period.

In the two centuries from 1700 to 1900 the core of that dominant power completely collapsed. We don't need to concern ourselves with the periphery, which dropped away from the core fragment by fragment during this period. In 1804/6 Emperor Franz II acknowledged, not too unhappily it seems, that the old empire was gone and its successor would now be the 'Austrian Empire' of which he would now become Emperor Franz I, much to the confusion of the generations of historians, archivists and schoolchildren ever since, who now know him as Franz II/I.

That Austrian Empire would last another century until it was officially buried at the conclusion of the First World War. Joseph Roth (1894-1939) described the decrepitude of the final years of that rickety obsolescence in his magnificent novel Radetzkymarsch.

Once the Austrian Empire had gone there were now other dominant nations in Europe and the world, who spent the 20th century battering each other for total dominance. From this process the nations of the old empire stood aside, powerless, only playing a role as convenient battlefields on which the new masters of the world could play their games.

Wilhelm Gause (1853-1916), Hofball in Wien, 'Court Ball at the Hofburg in Vienna' (1900). Image: Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien.

Franz Joseph I and the glittering imperial facade of the Austrian court. The kissing and the glittering stopped abruptly 14 years later.

Why did the Austrian Empire collapse?

Centuries of historians have scribbled about this theme. We read about the characters and destinies of rulers, the fortunes of war, the expansion into the colonies, the role of trade, the growth of science and technology, the expansion of manufacturing and the creation of a broad bourgeois class. Although we do not begrudge these poor scribblers the bread they have put on their tables in the process, the scope of such enquiries is well beyond the range of even our broad brush.

But at the beginning of the twentieth century the German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) introduced a new factor that could contribute to the success or failure of a nation: The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, as he put it in the title of his ground-breaking work (1905). His thesis has never been refuted, but is often misunderstood in the English speaking world. His arguments are subtle and written in an extremely complex German that needs careful reading. The English translation by Talcott Parsons, done nearly 30 years after the original, though heroic, does not cope well with Weber's dense German.

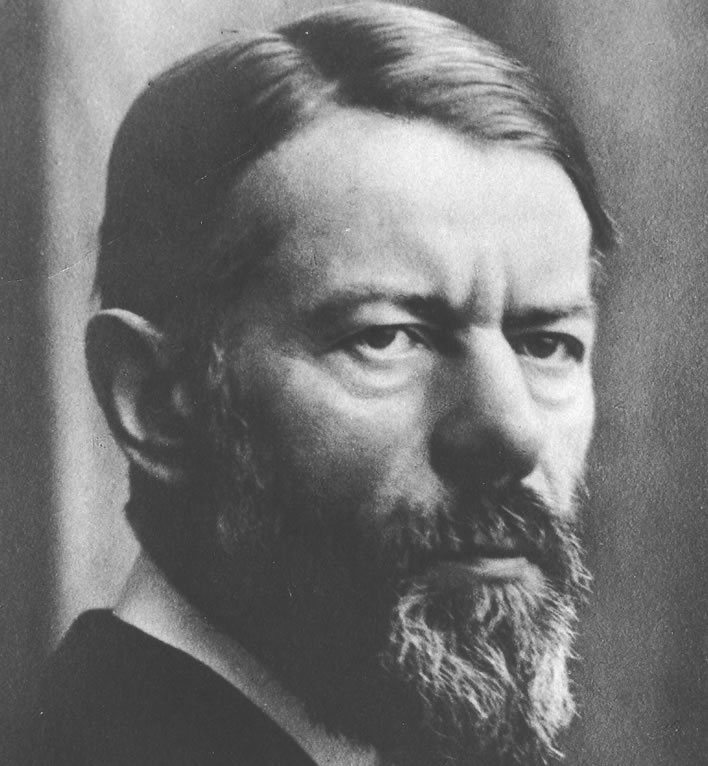

Professor Dr. Max Weber in 1918, looking rather like Captain Haddock, it has to be said. Image: Leif Geiges.

Let's use Weber's work to focus the question even more: 'What role did religion play in the collapse of the Austrian Empire?'

The feudal dinosaur

If we neglect the complex political machinations of those two centuries, the background is fairly clear. Maria Theresia, who saved the Austrian monarchy from extinction, took the throne in 1740. Around that time the Industrial Revolution was beginning in Britain. A few decades later it was also starting in Holland, Germany and then parts of France. These countries were innovating technologically, creating and mobilising capital, building factories, laying down an energy and communication infrastructure and moving away from being agricultural to being industrial societies. The two essential companions of technological progress were free trade and religious toleration.

In the new, technological world, mercantilism – the doctrine of price regulation and the top-down control of markets – was beginning to give way to the free market economics we associate with the name of Adam Smith: suddenly capital was released and profit and riches became acceptable and desirable. Mercantilism was not the sole domain of the Austrian Empire or of Catholic rulers, however. It was the trusted instrument of all the absolutist despots of the time, however 'enlightened' they were alleged to be.

Friedrich II ('the Great') of Prussia (1712-1786), the arch-enemy of the Austrian Empire, was an enthusiastic absolutist control freak and thus an enthusiastic mercantilist. Although nominally Protestant and nominally Calvinist, he was an unenthusiastic Christian who was thus able to work without distaste with whatever religious flavour of people he needed. He was happy to import Protestant workers into his kingdom, particularly the many who were harried and persecuted by the Catholic empire.

In the new, industrialised world that was arising, the old religious frictions gradually subsided. In Austria, however, Maria Theresia persecuted with great venom all flavours of non-Catholics, whether Protestants or Jews. There were expulsions into distant territories, long incarcerations, floggings and executions. Families were split up and children orphaned.

Her son and co-regent for many years, Joseph II, was aware of the precarious financial state of the empire and was desperate to harness the talents of Protestant tradesmen and workers. However, for Maria Theresia the thought of Protestants assembling and carrying out their heretical religious practices in her empire appalled her. It was only over her dead body that Joseph finally attempted to introduce his characteristically hotheaded and half-baked version of religious toleration into the Empire – only to fail miserably. The Austrian Empire was in its veins and arteries Catholic and would remain so until its end.

Adolph Menzel (1815–1905), Fronleichnamsprozession in Hofgastein, 'Corpus Christi procession in Hofgastein, Austria' (1880). Image: Neue Pinakothek.

One of the highlights of the Catholic year in Austria is the Corpus Christi procession. The Habsburg emperors participated in these processions whenever they could.

Whilst all this change was happening abroad, the rulers of the Austrian Empire were fussing about feudal levies and how much landowners could forcibly extract from their tenant farmers, religious tolerance, the central regulation of prices and the application of quotas and levies on imports and exports. And, of course, which books which people were allowed to read. For a thousand years the wealth of the empire had been locked up in land and feudal possessions; its riches had mainly come from agricultural production. The Austrian Empire was viewed by both its rulers and its people as the bastion of Catholic faith in an heretical world.

In short, the structure and organization of the empire was fundamentally inimical to an industrial revolution and it would remain so for a long time. For that reason alone, the Austrian Empire was heading for disaster.

But, if we follow Max Weber's thesis, the rot went even deeper.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!