Carl and Susanna Schubert

Richard Law, UTC 2016-05-24 08:41

Grandfather Carl

The composer Franz Peter Schubert's grandfather was Carl Schubert (1723-1787) a farmer in Neudorf, Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic). He has already appeared in this blog as an example of pious Catholic spending in our discussion of Max Weber's work Protestantism and the Spirit of Capitalism.

Neudorf (Nová Ves before 1948, then purged as a too obvious translation of the German 'Neudorf' to the current name Vysoká) was in the parish of Hohenseibersdorf (sometimes just 'Seibersdorf', now Vysoké Žibřidovice).

Central Europe 1789. Image: Wikimedia

Inset showing the main locations mentioned in this post. Neudorf/Hohenseibersdorf are in Moravia (Mähren), Zuckmantel is in Austrian Silesia (Österreichisch-Schlesien), the small southern area that was left to the Austrians after Friedrich II of Prussia had conquered Silesia.

Carl was one of a family of brothers, seven of his nine siblings survived childhood (an unusually high survival rate in the Schubert line). Carl's parents and siblings we shall leave unmentioned. Of Carl we know very little beyond the bare bones of the genealogical record, and even those bones have not always been re-assembled in the correct way.[1]

It is said that he served as a musician with the coalition army under the English king George II in Flanders around 1744 during the War of the Austrian Succession. Enthused by this possibly misleading scrap of information you are free to indulge in speculation about Franz Peter Schubert's musical genes, but speculation is all that it will ever be. You might just as well speculate that Carl also had the extreme shortsightedness that would later plague his grandson, the composer in the spectacles. In which case Carl may have been less risk to his own side with a pair of drumsticks or a flute than with a gun. Who knows?

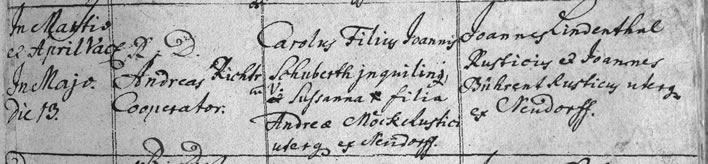

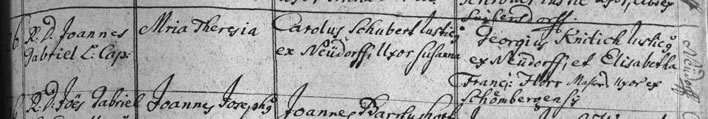

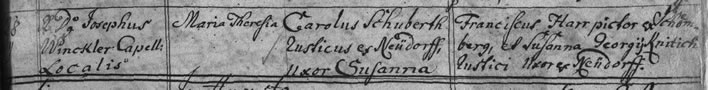

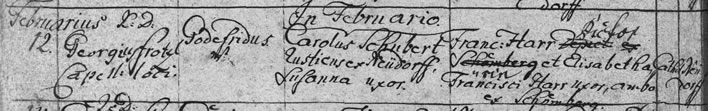

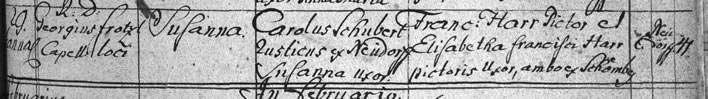

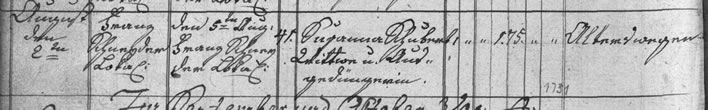

We do know, however, for here is the evidence[2], that in 1754, aged 31, he married the 23 year old Susanna Möck (1733-1806), the daughter of a local farmer:

13 May 1754: Carl Schubert and Susanna Möck marry. It is stated that he is an inquilinus, a householder (possibly tenant) with a small amount of land. This is an extract from the marriage register of the parish of Hohenseibersdorf for 1754.

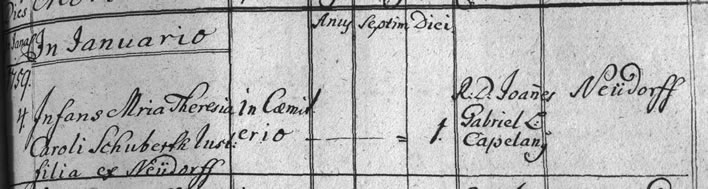

Carl progressed from being a farm worker with house and smallholding (inquilinus) at the time of his wedding to Susanna to becoming a farmer in his own right (rusticus) five years later when he bought the farm of his father-in-law in January 1759.

Emile Claus (1849–1924). Top: Flax Weeding in Flanders, 1887. Bottom: The Flax Harvest, 1904. Images: Royal Museum of Fine Arts Belgium.

Belgium not Moravia, nineteenth not eighteenth century, but the principle holds good: growing flax, which we assume was the staple crop of Carl's region, is hard, backbreaking work.

Carl married wisely and seems to have bought and sold property advantageously. He is said to have successfully represented the local farmers in their confrontation with their feudal rulers, the House of Goldenstein, and acquired at some point the post of local magistrate (Dorfrichter). As such he would have had a wide range of important duties: determining the times of sowing and harvesting and which fields were to be cultivated for what crop; mediating or deciding disputes; acting as a guardian of morals and deciding whether wrongdoers were to be handed over to higher authorities; acting as an enforcer and mediator between the villagers and the feudal lord. Carl was clearly a successful, trusted and respected man in his village.

Carl and Susanna's children

Carl and Susanna brought 13 children into the world. Only two sons, Johannes Karl and Franz Theodor, and two daughters, Maria Theresia and Anna Maria, survived into adulthood. Clearly, the good survival rate of Carl's siblings did not pass down to his own children, nor to his grandson Franz Theodor's children.

| No. | Name | Birth | Death | Age | Remarks |

| 1 | Johann Karl Alois | 03.04.1755 | 29.12.1804 | 49y8m | The composer's uncle |

| 2 | Franz Anton | 06.01.1757 | 11.08.1762 | 5y7m | 1762 epidemic |

| 3 | Maria Theresia (1) | 04.01.1759 | 04.01.1759 | <1d | |

| 4 | Maria Theresia (2) | 26.11.1759 | 19.08.1762 | 2y9m | 1762 epidemic |

| 5 | Johann Joseph (1) | 22.10.1761 | 04.09.1762 | 11m | 1762 epidemic |

| 6 | Franz Theodor Florian | 11.07.1763 | 09.07.1830 | 66y | The composer's father |

| 7 | Maria Theresia (3) | 28.07.1765 | after 1830 | ||

| 8 | Anna Elisabeth | 18.09.1767 | 01.10.1781 | 14y | |

| 9 | Anna Maria Thekla | 02.05.1770 | after 1830 | ||

| 10 | Susanna | 29.01.1773 | 22.02.1773 | 7w | |

| 11 | Gottfried | 12.02.1774 | 14.02.1774 | 2d | |

| 12 | Johann Joseph (2) | 04.08.1775 | 19.09.1775 | 6w | |

| 13 | David | 27.01.1778 | 27.01.1778 | <1d |

Carl and Susanna Schubert's children

Surviving brothers Surviving sisters died 1762 epidemic

Let's be real historians and examine the documentary record, thus allowing us not only to verify our dates but to track Carl Schubert's changing status during the couple's 20 year period of child bearing as well as the composition of the family.

There is a long tradition in the secondary literature of getting Schubert dates wrong, so that if we refer to the sources for at least the most important dates we shall be less likely to be led into errors. Caution is still required: such records are not always accurate – every researcher has favourite examples of wrong dates, wrong names and other nonsense scribbled by drunks in freezing sacristies by sputtering candlelight in midwinter – but they are always the authentic starting point.

The dates given here in the registers are the dates of baptism: the Church, the keeper of records at the time, was less interested in birth, only the date of entry of the sheep into its fold. In the present account we may as a sloppy convenience refer to these dates as birthdates, although these are mostly unknown.

There was, however, given the child mortality of the times, an urgency to baptise an infant as soon as possible so that it might not die unbaptised (in Catholic theology the unbaptised had no access to heaven), meaning that if the birthday and the baptism did not take place on the same day, we are usually only late by a day. If this inaccuracy at a distance of two and a half centuries troubles your sleep, history may not be your subject.

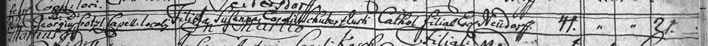

3 April 1755: Carl and Susanna's first son, Johann Karl Alois is born (the uncle of the composer). Carl is an inquilinus, a smallholder.

6 January 1757: Franz Anton is born. He will die in the 1762 epidemic. Carl is still an inquilinus. The writer originally put domuncularis, tenant, then crossed at least part of that out and inserted inquilinus. Let's forgive him: it's deep winter in the hills of eastern Moravia.

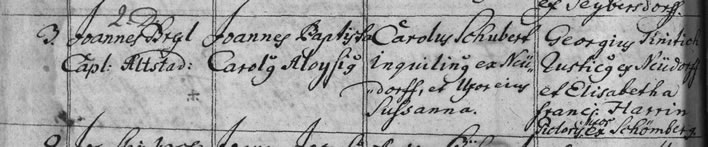

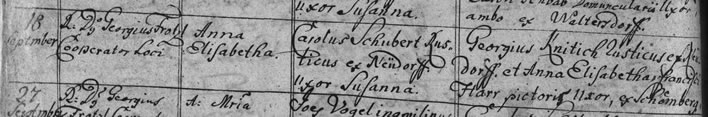

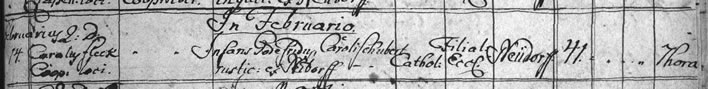

1 April 1759: Maria Theresia (1) is born and dies on the same day. Carl is now a rusticus, a farmer, having bought his father-in-law's farm. He will retain that status on all the remaining entries. The transaction was completed on the day that Maria Theresia was born and died. A child that is born and dies so quickly does not have a baptismal entry (there was no time to write it) but only a death entry.

26 November 1759: Maria Theresia (2) is born. She will die in the 1762 epidemic.

22 October 1761: Johann Joseph (1) is born. He will die in the 1762 epidemic.

The Grim Reaper plague: the disease years 1762-3

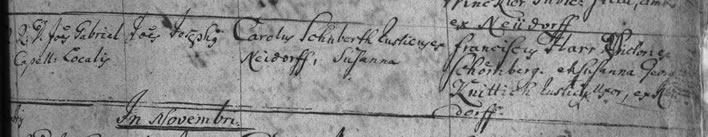

In 1762-3 an epidemic disease scythed through the population of Neudorf. We can see this easily in the death register:

1762, the epidemic summer: The Carl and Susanna lose three children within a month. The grim reaper takes Franz Anton [5y6m], Maria Theresia (2) [2y26w] and Johann Joseph [45w]. The oldest child, Johann Karl Alois, now becomes the only child in the family.

Not shown here is the month of July, which contains a long list of infant deaths in the parish – we can expect the epidemic to have swept away the newly born, the most vulnerable, first before killing young children and old people.

The two years 1761 and 1762 were dark ones for the people of Neudorf and Hohenseibersdorf. In good years there would be a rough average of 15 more births than deaths, a healthy population growth. In the years 1761 and 1762, however, the Grim One reaped dutifully and the population shrank two years in succession and barely recovered by the third year:

| Year | Baptisms | Marriages | Deaths |

Newborn deaths |

Baptisms minus deaths |

| 1760 | 41 | 5 | 20 | 2 | +21 |

| 1761 | 28 | 5 | 47 | 1 | -19 |

| 1762 | 34 | 5 | 48 | 8 | -14 |

| 1763 | 37 | 6 | 36 | 4 | +1 |

| 1764 | 35 | 9 | 13 | 2 | +22 |

| 1765 | 42 | 6 | 33 | 3 | +9 |

Table 1: Life and death in the parish of Seibersdorf/Neudorf in the plague years 1761-3.

In a normal year two or three newborn babies would die. In 1762 nearly eight of the 48 deaths were newborn children. It was only after 1763 that the population started to recover from the disaster.

The Schubert family rebuilds

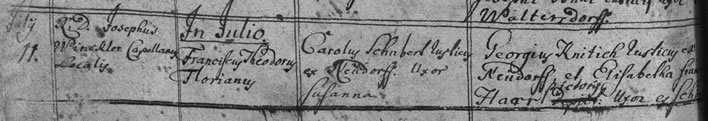

By September of 1762 the epidemic had run its course, leaving the Schubert family a wreck with only one child left, the first born, Karl. The seven year-old was now an only child. The resiliance of the rustic poor is always astonishing: another child was conceived with little delay and arrived in July of the following year. In time he would become the composer's father, but for the moment he was Franz 'Theodor', the 'gift of god':

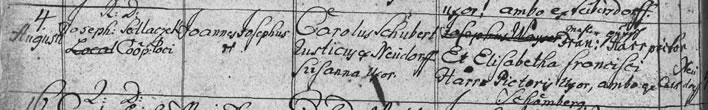

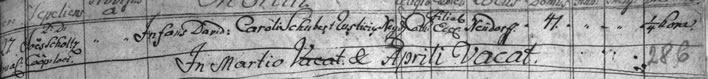

11 July 1763: Franz Theodor Florian is born (the father of the composer), fortunately after the plague years, otherwise we might have had neither father nor composer. Franz Theodor is now the second child of the family with an eight year older brother.

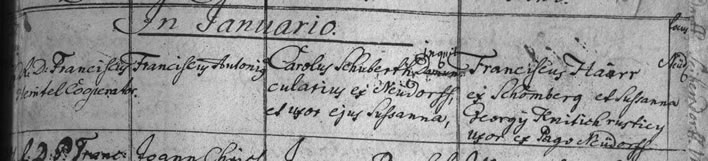

28 July 1765: Maria Theresia (3) is born. She is one of the two daughters who will live to a good age.

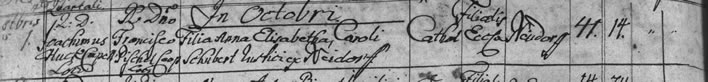

18 September 1767: Anna Elisabeth is born. She will die 14 years old on 1 October 1781.

Johann Karl and Franz Theodor left for school, the Jesuitengymnasium in Brünn, in the autumn of 1769, so that for most of the year 1769-70 the family had now just daughters in the house.

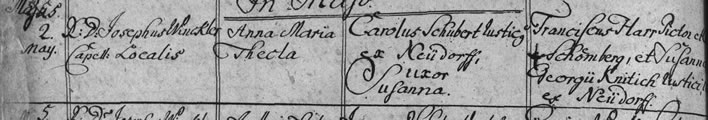

2 May 1770: Anna Maria Thekla is born. She is the second daughter who will live to a good age.

There was now a reproductive gap of four years, corresponding to the three 'hunger years' that struck the north European continent in 1771-73. Franz Theodor took a three year break from the Jesuitengymnasium during these three terrible years.

Let us give heartfelt thanks for the fact that scarcely anyone who reads this account of the Schubert family will have had any experience of that terrible thing, starvation hunger. Let us step aside briefly from our family chronology to try to gain an idea of what these three 'hunger years' in Europe meant for those who experienced them.

The Grim Reaper famine: the hunger years 1771-3

The 'hunger years' of 1771-3 were three years of catastrophically wet and cold weather throughout most of central and eastern Europe, that brought desperate food shortages and extremely high food prices. We have no account from anyone how these years directly affected Carl and his family, the other villagers of Neudorf or indeed the region – as usual, few personal experiences were written down.

The rulers of the affected regions, when they finally realised what a disaster was taking place, set up committees and launched themselves into mercantilist distribution and price fixing, to little effect. Surveys were initiated, statistics collected and minutes of meetings written and filed, but it takes a fine imagination to convert these stacks of paper into human experience.

But we can form some idea thanks to a remarkable diary written by a farmer in the village of Rohne in Saxony, Hanso Nepila (1766-1856). The members of the agricultural classes at that time were rarely taught to read and even more rarely taught to write. Hanso had taught himself both skills and wrote a diary with almost obsessive intensity.

He had not only taught himself the skill of writing but also possessed the psychological tic of all the great diary writers, an obsessive drive to communicate with an imaginary other, even when there was no one to read his work. He would write his diary, although mocked for it by many, particularly his shrewish wife, whenever he had a moment in his grinding existence. He was writing in his mother tongue, Sorbisch/Wendisch. He had no literary models apart from the Bible and wrote without literary affectation.

He was a child during the hunger years, but wrote an account of the suffering of that time. Hanso's village of Rohne was in Saxony (close to Leipzig), not Moravia, but is only about 150 km north of Neudorf (250 km in a direct line) and the climate and the hardships would have been very similar. Hanso's account gives us a good idea of what the hunger years must have been like in Carl's village of Neudorf.

At that time it was a very wet year and a very poor year and a very hungry year. The rye didn't grow, just tiny stalks, nothing came of it. The buckwheat didn't grow at all. On the hills people pulled up what they could, but there was nothing in the valleys, only water knotweed and wild rye. There was so little to gather that it could be carried home by hand in a bundle. The millet scarcely appeared above the soil and never came to anything. What rye we had was threshed and then sown again. There was not enough to sow fully, so they had to buy it in, if it could be bought. Is was very expensive. … Oh that was an expensive year. Oh that was a very hungry year in Saxony and in the whole Empire! In both countries it was very expensive and people were very hungry and had nothing to eat so that they had to go off begging on the roadsides for a few pieces of bread. … Some of these people were so weak and hungry that they sat at the roadside and couldn't go a step further.[3]

It was essential to keep enough grain back to use as seed grain for the following year. The only things then left for the peasants to eat were the leftovers of the threshing:

We milled chaff from the rye and flax and oats to flour and baked bread from it and ate the bread. It was so cracked and scratchy and dry that we could scarcely soften quickly enough it in our dry and weak mouths in order to eat it faster because we were so hungry. And the bread was so dry and crumbly that the loaf couldn't hold together or stay in one piece. They would turn the loaves on the baking shovels, squeeze them back together and put them back in the oven. They broke up again and the pieces could only be got out of the oven with the fire irons. Just pieces, not a single loaf. They carried the pieces in their aprons and tipped them onto the table and we ate them. And they swept the crumbs together with a brush and we used a spoon to put them in our mouths and we ate them. It just looked like horse manure, dry and crumbly. And even so we were glad to eat it, it was better than dying of hunger. I also ate it, I know how it was and and how tasty it was. I am not lying, my Lord God knows that I am not lying[4]

As the third horseman, Famine, rode through the land, at his side as ever was the fourth horseman, Fear, Disease and Death. In parish registers of the time, on average, deaths outnumber births by five to one. The weakened population declined. There were two bad harvests without the chance of recovery.

St. Anthony's Fire

The cold winters and late, wet springs were the textbook conditions for the infection of the cereal rye – the staple food of the peasants – with the ergotism fungus. Other types of cereal could also be infected, but rye was the most common and the most widely used source of flour for peasant bread. If the fungus growths on the grains were milled into the flour everyone who ate that flour would get a dose of the nerve poison in the fungus.

The symptoms of Ergotism came in two main forms: the gangrenous form, St. Anthony's Fire, with burning sensations, skin eruptions and finally a painful gangrene when limbs rotted and fell off; and the convulsive form (Kriebelkrankheit), with itchy skin, diarrhea, vomiting and terrible cramps in the extremities that could last for hours. Both forms almost always ended in death. The widespread outbreaks of this dreadful disease in these hunger years would eventually lead to legal measures to prevent the use and distribution of uncleaned grain.

What small grain reserves could be laid down often just rotted in the cold, damp atmosphere. Leaving ergotism aside, many people died from illnesses caused by eating mouldy and rotten grain. Among a population weakened by hunger and cold there were epidemics of diseases such as dysentry and typhus. Livestock died of hunger and disease. In the end, begging was for many the only option:

[My father went begging.] After two days he came home and we were expecting that he would give us a lot of bread and that we could once more fill our bellies after not having anything to eat for such a long time. Father tipped the bread he had got for his begging out of his bag onto the table and there no more than five crusts, still with teeth marks in them. That was to be our joy! And our mother softened the crusts for us in water and we ate them; they were very small[5]

Staying alive

Hanso also tells us how he used a traditional trick to try and stay alive during famine: eating clay. Clay contains some of the salts and minerals that are essential for metabolic functions. For this reason, when Hanso's parents did get a little money they not only bought flour but also salt. There can be no life without salt.

My father had a store of clay. I went to the clay and sat down next to it and tried to eat some of it. And I made small pancakes of it and tore off and ate pieces of them. I was still hungry, but I didn't like it and couldn't eat much. I went and lay down to sleep. And my God and my Lord kept me alive and I awoke early and healthy, with God the all powerful Lord. He feeds and keeps us all and does not allow us to die of hunger. … I was still hungry, so I took a small bowl and put a bit of water in it. And I took a spoon and went to the clay again and put a lump of it about as big as a hen's egg in the bowl and stirred it up well with the water and made a sort of flour soup and ate it all up and slept well.[6]

The hunger years in Neudorf

The hunger years were felt in Neudorf and its surroundings, too. We have no record of the suffering there, but we just need to look at the population changes during the period for the locality:

| Year | Baptisms | Marriages | Deaths |

Newborn deaths |

Baptisms minus deaths |

| 1769 | 43 | 6 | 30 | 1 | +13 |

| 1770 | 37 | 12 | 23 | 1 | +14 |

| 1771 | 35 | 8 | 30 | 2 | +5 |

| 1772 | 24 | 7 | 59 | 2 | -35 |

| 1773 | 32 | 2 | 44 | 1 | -12 |

| 1774 | 38 | 12 | 27 | 2 | +11 |

Table 2: Life and death in the parish of Seibersdorf/Neudorf in the hunger years 1771-3.

In Neudorf and Hohenseibersdorf the succession of normal years ended in 1770. The hunger years 1771-1773 were characterised by cold and extremely wet springs and it should not surprise us that the most fatal months were in late winter and early spring: once the sequence of bad weather had started in 1771 there were almost no reserves from the previous bad year and the effects of the shortages were felt most when the paltry supplies ran out in mid-winter.

We have no direct record of how the hunger years affected Carl Schubert and his family in Neudorf. However prudent we imagine him to be, he cannot have been immune from the effects of this catastrophe. Whether as farmer or as dealer, the shortages and high prices must have affected him considerably. The fees that farmers like him had to pay to the feudal landowners together with the feudal labour they had to carry out were not necessarily reduced in bad times. Perhaps Carl needed to save money more than he needed to avoid an extra mouth to feed. We don't know. His son Karl kept on at the Jesuit school during this period, as did two boys from Hohenseibersdorf, Karl Lengsfeld and Hieronymous Reineldt.

Recovery

The seven year-old Franz Theodor had returned from the Jesuitengymnasium in the summer of 1770 and remained at home for another three years, covering the period of the 'hunger years' and the reproductive gap. He returned to school in 1773, now a ten year-old. He would complete the remaining five years in sequence.

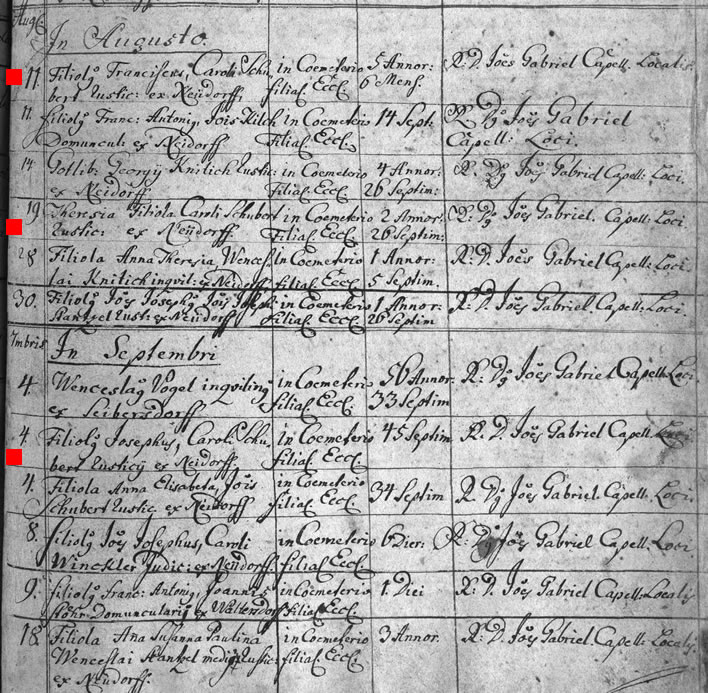

In 1774, when breeding starts again, Susanna is 43 years old. The four babies that are produced from then onwards all die in early infancy:

12 February 1774: Gottfried is born. He dies two days later on 14 February 1774.

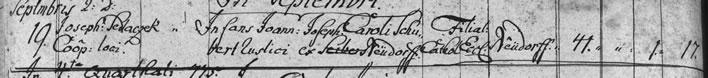

4 August 1775: Johann Joseph is born. He dies 6 weeks later on 19 September 1769.

29 January 1773: Susanna is born. She will only live about 6 weeks, dying on 22 February 1773.

27 February 1778: David, the couple's last child, is born and dies a few hours later.

In the summer of 1775, the year Johann Joseph was born, Johann Karl successfully completed his time at the Jesuitengymnasium in Brünn. If he returned to Neudorf it was only for a short while before he set off to Vienna.

Now, in 1778, we can allow ourselves a sigh of relief on behalf of the now 47 year-old Susanna that her 24 years of procreation (including eight dead babies) have finally come to an end. She has 28 baby-free years ahead of her. Carl, now 55, puts his mind to his Ölvater, which he will complete in 1780.

1778 is also the year the Franz Theodor leaves the Jesuitengymnasium and goes off into the big wide world, following his brother Karl to Vienna.

Carl and Susanna, the later years

By 1780 the pious Carl was wealthy enough to erect his Ölvater on the ridge above Neudorf, as we have already noted. In 1782, only two years after he had erected his Ölvater he was involved in even more pious spending. He joined with two of his nephews – Joseph Johann (1741-?), son of his brother Joseph (1707-1756) and Johann Joseph (1747-1804), son of his brother Johann (1712-1763) – to build a chapel in Neudorf: the 'Chapel of the Holy Trinity'. They finished this project in 1786.

In 1787, seven years after his Ölvater was finished, Carl died of a perforated bowel. Franz Theodor recorded this in the family chronicle:

On 16 December 1787 at three-thirty in the morning my dearly loved and respected father Karl Schubert died.[7]

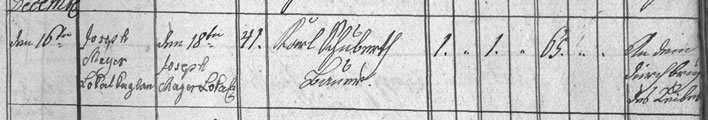

16 December 1787: Carl Schubert dies.

Susanna survived her husband, living a further 19 years in the family house until she died, 75 years old in 1806. Unlike the death of her husband, her passing was not documented in her son Franz Theodor's family chronicle; the otherwise so punctilious school teacher made no entry at all for her. Did she in turn know of her oldest son, Karl's death in 1804?

2 February 1806: Susanna Schubert dies.

It is saddening to realise how little we really know about Carl and Susanna'a family. Had Franz Theodor simply lost touch with the distant Moravian village of his childhood? Once Susanna died did no one in Neudorf know anything anymore of the the two brothers who had set off into the wide world more than thirty years before? In his 'family list' was Franz Theodor just following the genealogical tradition of patriarchal societies and only recording the male line?

Carl and Susanna were both buried at Hohenseibersdorf, but as far as I know no graves now exist for either of them. The only Schubert grave there dates from 1917. Their family house was in Neudorf, no. 41, across a small field from the chapel which the brothers had built. It was perched on the edge of the small valley to the east of the village. The Ölvater stands on the ridge opposite and was visible from the house.

The Schubert family home in Neudorf in 1930.

The house was 'inadvertently demolished' in 1960, along with 31 other houses in the village. At the time of writing the foundations are still visible: a few layers of stones form the low remains of thick walls overwhelmed by grass and bushes.

Houses live and die: there is a time for building

And a time for living and for generation

And a time for the wind to break the loosened pane

And to shake the wainscot where the field-mouse trots

And to shake the tattered arras woven with a silent motto.[8]

The Schubert family home in Neudorf in 2013, after the postwar expulsions of the German-speaking inhabitants of 'Sudetenland' by communist Czechoslovakia and the subsequent razing of their property. Throughout Moravia and Silesia the story was the same: many properties of the former inhabitants and even whole villages stood empty, fell into ruins and were razed without trace. Image ©: Jan Malach

Moravia: what's left

We stand here in this rolling landscape in an attempt to recover Carl and Susanna's world from two and a half centuries ago. We cannot do it. Apart from the Ölvater there is nothing left here except some almost forgotten rubble and a fake, reconstructed chapel. Between the Schuberts and us are two and a half centuries of upheaval, revolution, repression, persecution, expulsion and slaughter, culminating in the disasters of the twentieth century.

After the First World War a Czechoslovak Republic was created by fiat out of a mix of territories with German, Czech and Polish speakers. The aggregation of the German speaking enclaves in the region was known from the German viewpoint as the Sudetenland.

The discontent of the substantial and vocal German-speaking minority under their Czech masters, who, it must be said, seem to have gone out of their way to humiliate the citizens of German descent, festered for nearly twenty years until – with the shameful cooperation of the British and the French governments – the Sudetenland was handed over to Nazi Germany in 1938. The 'Peace in our time' that was bought with this handover did not last long, though, and the German conquest of the rest of Czechoslovakia followed in March 1939.

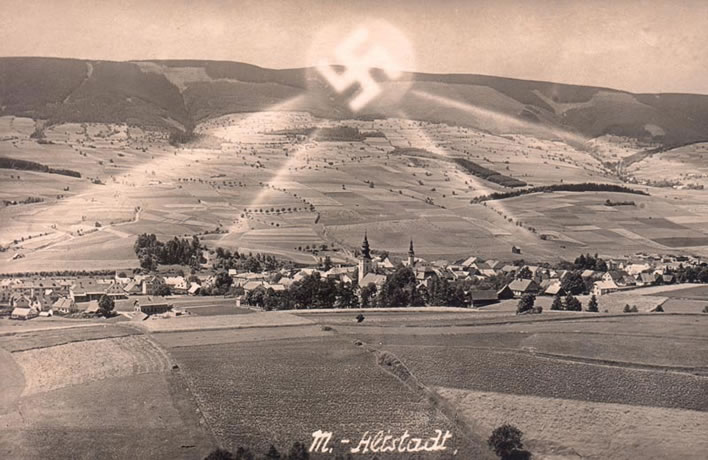

A postcard of Mährisch Altstadt from 1941 for tourists to send back home. The swastika shines down on the town of Mährisch Altstadt (now Staré Město in the Czech Republic), not far from Neudorf. After the annexation by the Germans in 1938 the region was called the Gau Sudetenland, Gau being a Nazi term for an area of territorial organization under a provincial governor, a Gauleiter.

Image: Datenbank des Landschaftsgedächtnisses.

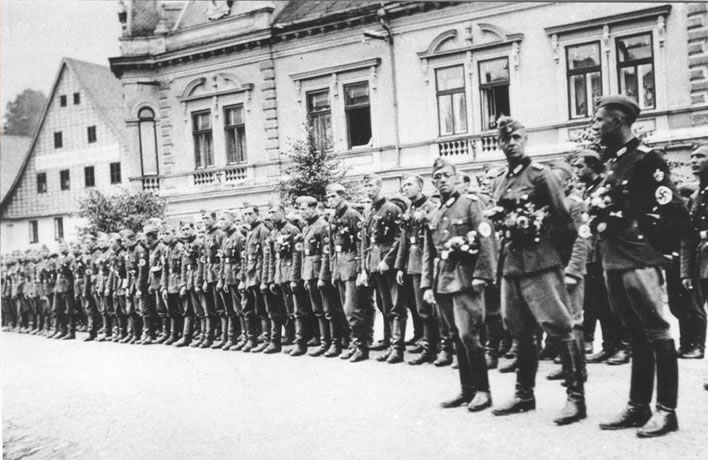

Top: the German saviours of the town in 1941. Bottom: the Russian saviours of the town in 1946. So it goes.

Images: Datenbank des Landschaftsgedächtnisses.

The area was ethnically cleansed of Jews and dissidents – whether Czech or German – and all resistance by Czech speakers was put down. After the war, when the communists took over the region in 1945, the German-speakers, nearly four million of them, were in turn brutally driven out. Many had been enthusiastic Nazis before and during the war and nemesis followed hubris as night follows day. The Czech revenge was sweet and inhumane: who would speak on behalf of these German outcasts? No one.

During that expulsion, the German-speaking inhabitants would typically be given a day's notice and then an hour or two on that day to collect the belongings they were allowed to take with them, typically up to a limit of 20 kg. Everything else – furniture, bedding, motor vehicles, every kind of possession – had to be left behind. 'Don't forget to leave the key on the outside of the door', they were told. Were there any sabotage to the possessions they left behind, they would be shot.

The families walked to collection centres from where they were transported in railway wagons into what remained of Germany, whose inhabitants, themselves in terrible distress after the war, were understandably even more distressed to have even more hungry, homeless mouths to feed. Their numbers from Czechoslovakia alone were estimated to be more the three million people; overall somewhere between 11 and 15 million people were driven out into postwar Germany.

In the new Communist state of Czechoslovakia the abandoned buildings were cannibalised, left to decay and then bulldozed when they got in the way of mechanized farming. The area around Carl and Susanna's village of Neudorf was a solidly German-speaking settlement and was effectively emptied of its inhabitants. The hamlet of Cibulkenfeld, just a little to the northwest of Hohenseibersdorf, had 16 or so empty buildings still standing in 1953; today there is no trace of it. Most of the German inhabitants of the area around Neudorf were resettled around Fulda in Hesse, a strongly Catholic region in what was to become the Federal Republic of Germany ('West Germany').

The Sudeten Germans had been proud of their paternity of the famous composer: plaques were erected, the Schubert family house was restored. After the Czechs had driven the ethnic German people out they also purged whatever Germanic artefacts were left behind. The Schubert house was abandoned and then demolished. Even the Chapel of the Holy Trinity that Carl and his brothers had built was destroyed at some time in the years from 1948 to 1989 and left as a burnt out ruin. A cowshed was built next to it. It was recently rebuilt with the help of private and public donations and this photogenic fake has now taken its place in the modern Schubert tourism in the area.

We should not forget that it is a fake, however beautifully reconstructed, otherwise we risk forgetting what really happened here. Nor should we rebuild the Schubert house: the stones that are the only things left of it are more eloquent than any museum replica.

Where was the wall of Eblis

At Ventadour, there now are the bees,

And in that court, wild grass for their pleasure

That they carry back to the crevice

Where loose stone hangs upon stone.[9]

References

-

^

Most of the assertions and narrative about the Schubert ancestors are passed around from book to book without reference to any primary sources. The tradition is to pass on such fairy tales unexamined, after adding a few of one's own fantasies.

Where I have had no direct access to sources I have relied on Schöny, Heinz. ‘Franz Schubert. Herkunft und Verwandschaft’. Jahrbuch der Heraldisch-Genealogischen Gesellschaft „Adler“ dritte Folge, Band 9.1974/78 (1978): 1–26. I have also compared and extended Schöny's results with matierials from other sources, particularly De Clercq, Robert O. Franz Schuberts Ahnen und Verwandte in Mährisch Schlesien. Brno: N.p., 2000. Studia minora facultatis philosophicae Universitatis Brunensis H 35. De Clercq had access to a family tree that is in a private collection. - ^ All entries from the parish registers are taken from inv c 5813 sig Ba XIII 1 1735-1785, Vysoke zibridovice - Vysoka - Zleb.

- ^ Jahn, Peter Milan. Vom Roboter zum Schulpropheten Hanso Nepila (1766-1856): mikrohistorische Studien zu Leben und Werk eines wendischen Fronarbeiters und Schriftstellers aus Rohne in der Standesherrschaft Muskau: mit einer Übersetzung der Handschriften . Bautzen: Domowina-Verlag, 2010. p. 645f.

- ^ Ibid. p. 647f

- ^ Ibid. p. 651

- ^ Ibid. p. 651f

- ^ A commented transcription of the entries in Franz Theodor's Verzeichnis der 'Geburts- und Sterbefälle in der Familie des Schullehrers Franz Schubert' is available in Deutsch, Otto Erich, ed. Schubert: die Dokumente seines Lebens. Erw. Nachdruck der 2. Aufl. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1996. p. 4.

- ^ Eliot, T.S., 'Four Quartets', 'East Coker' in Collected Poems 1909-1962, London, 1963, p. 196.

- ^ Ezra Pound, The Cantos, Faber and Faber, London, 1975, 'Canto XXVII', p. 132.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!