The two brothers

Richard Law, UTC 2016-05-24 08:42

Carl and Susanna's two sons who survived were separated by eight years: the eldest child (Johann) Karl (Alois) Schubert (1755-1804) and the future father of the musical genius, Franz (Theodor Florian) Schubert (1763-1830).

Johann Karl, a seven year-old in 1762, survived the epidemic disease – possibly cholera or typhus – that came to Neudorf in 1972 and killed his three siblings, children aged between five and one, all within the space of about three weeks.

Franz Theodor, our composer's father, was born in the first year after the crisis, 1763. From his point of view he was the second child of a family of two, which may account for the fact that despite the age difference, the brothers remained close for the rest of their lives: their paths and their destinies intertwine closely for about forty years.

We know almost nothing about the brothers' early lives. Assuming that the parents could read, we know of no letters from the brothers to their parents that have survived the turmoil of the centuries in Moravia – it would be a miracle as great as the survival of Carl's Ölvater if some bundle of letters had made its way into Germany intact during the expulsions at the end of the Second World War. Given all the terrible things that happened in the intervening centuries it seems churlish to fuss about a few letters that might have been written from the imperial capital by dutiful sons that may have been lost forever. We have reconstructed a few dates from parish records that have managed to survive, but at all the human things in their lives – motives, purposes, desires, happiness and sadness – we can only guess. Better not to try.

Leaving the nest

One geneologist considers it one of the great puzzles that Karl and Franz Theodor did not follow their father into farming. I, on the contrary, think it is a question that is easily answered.

Firstly, there was no economic reason for either of Carl Schubert's sons to follow in his footsteps as farmers. Carl had brothers with extended families and daughters who had made good local dynastic marriages. There is a limit to the number of inhabitants a small farming community can support. About three years after Carl's death his house and farm – still the residence of his widow and her widowed sister – were taken over by a stepson, Florian Harbich, who had married Carl's younger daughter. The population of Neudorf, despite the setbacks, was growing and the village simply did not need more farmers.

Secondly, once farming had been ruled out, the only respectable path open to his sons in the mind of a pious peasant farmer was the priesthood. We have seen plenty of evidence of Carl Schubert's profound piety: the Ölvater and the chapel of the Holy Trinity. In Carl's religious mind, the two boys in his family, who by divine intervention had been spared, were a gift to him from the almighty – we note again the second son's second name: Franz Theodor, the gift of God, the one who arrived and lived after so many had died. That gift had to be used fittingly and the dedication of their lives to the priesthood was the only possible response. It seems unlikely that Carl would have ever expected them to become teachers.

Carl, of course, thought as a pious, simple believer woould, whereas the sociologically inclined modern is already thinking of the Catholic Church of the time as being a well trodden path of social mobility for the sons of the land. This path of social mobility was a particularly Catholic phenomenon that arose from the celibacy of the Catholic priesthood: there had to be a constant supply of new priests to feed the system. Protestant clerics, in contrast, took wives and produced children, thus creating family dynasties in which the living would be handed down from father to son, almost as a farm or a house would be. Without some luck, therefore, it was difficult for a new Protestant cleric to get on the clerical ladder or change to another living.

Let us assume that the brothers went for their early education, one after the other, to the local parish school in Neudorf. It appears that at some point they went on to be schooled by a certain Andreas Becker in Hohenseibersdorf.

Perhaps the two brothers started their education in Neudorf and then moved to Becker's teaching to get the Latin and German education they would need for their next step. Who knows? But we can assume that the next step in Carl's mind was the entrance to the Jesuitengymnasium in Brünn and from there into the priesthood.

Both boys would be very familiar with the walk over the Ölberg to and from Becker's school, although at that time, of course, without the Ölvater to guide them. He came ten years after they first left Neudorf.

The brothers in Brünn

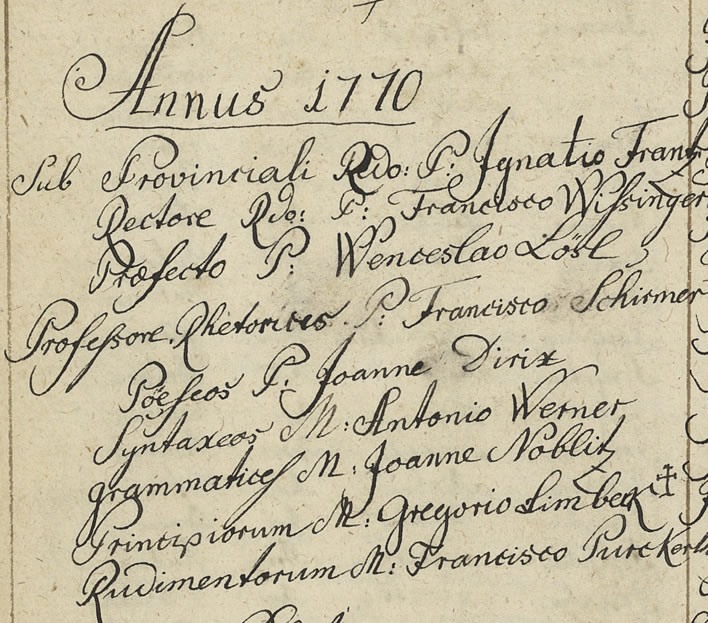

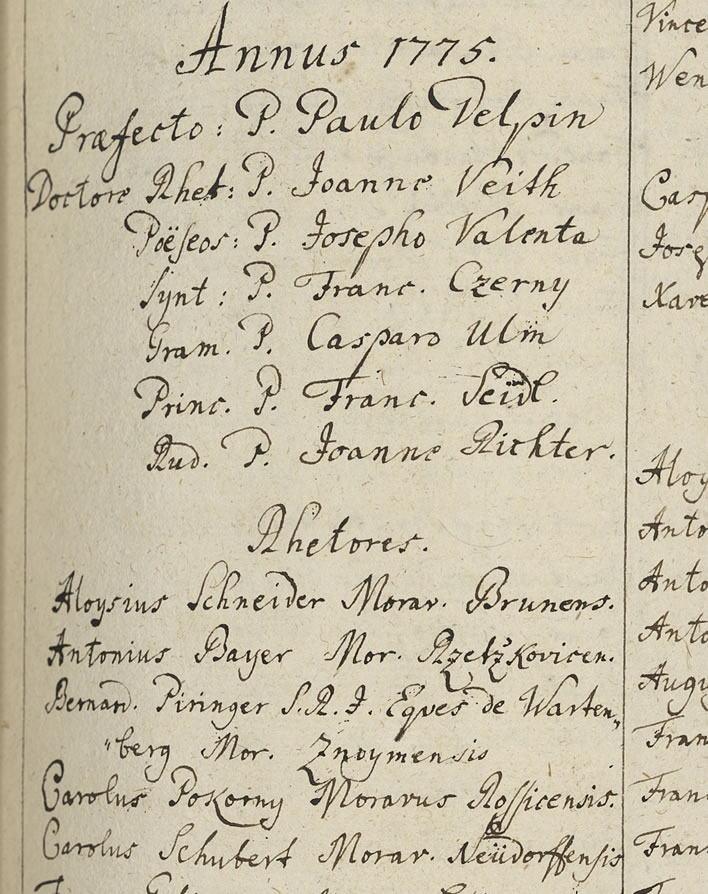

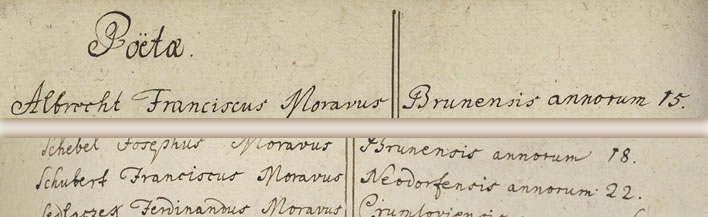

Both brothers were sent for their secondary education to the Jesuitengymnasium, the Jesuit High School, in Brünn, the capital of Moravia. I have found no record of either having a scholarship, but we are not surprised that in the ten years before he erected his Ölvater, Carl could afford the tuition fees and the costs of accommodation in distant Brünn. Strangely enough, despite the eight year age difference, Karl (14) and Franz Theodor (6) started at the high school at the same time, in the autumn of 1769.[1]

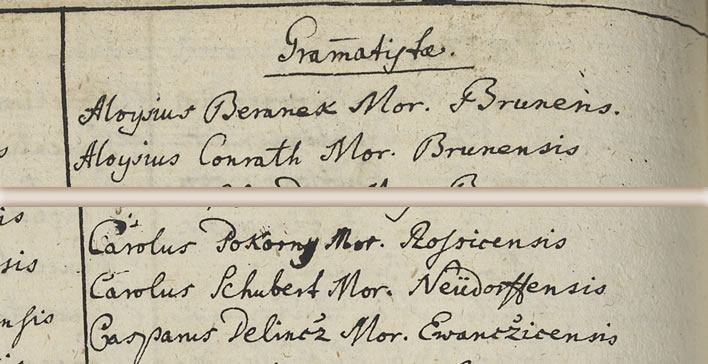

The brothers arrive in the Jesuit High School in Brünn, Moravia, in 1769.

Note 1: These lists are of the pupils at the end of the academic year. 1770 here means the academic year 1769-70.

Note 2: The course was six years long. Unfortunately the names of the class years were changed several times during the brothers' education in Brünn, which means we have to keep track of the names. In 1770, therefore, we have in ascending order: Rudimentorum, Principiorum, Grammatices, Syntaxeos, Poeseos, Rhetorices.

Note 3: The children are listed in the order of their Christian names (that being, in the eyes of the Jesuits, the name of the child before God).

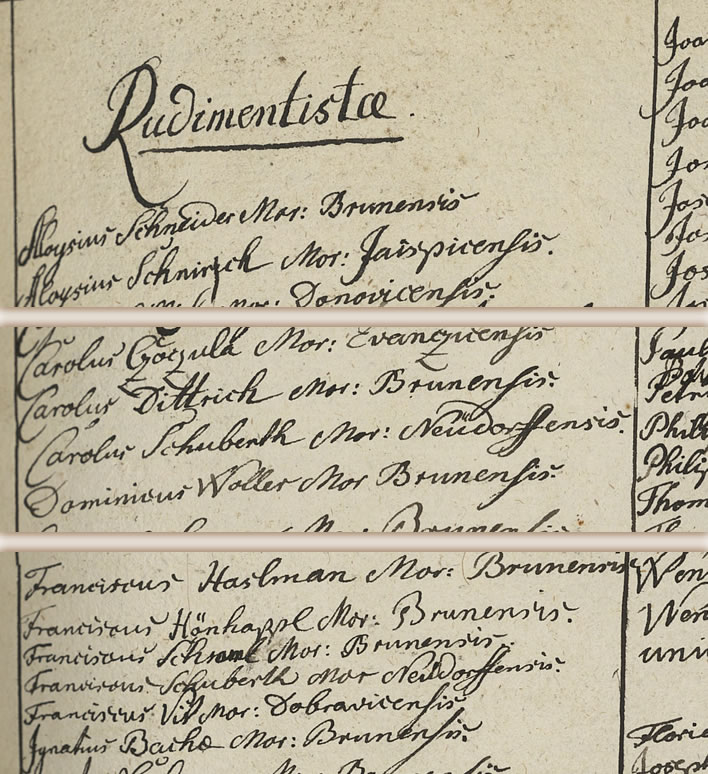

The entries in the class Rudimentistae for Karl Schubert (aged 14 at the start of the school year, about the average age for the first year), Carolus Schuberth Mor[avia] Neudorffiensis, and his brother Franz [Theodor] Schubert (aged six!), Franciscus Schuberth Mor[avus] Neudorffiensis.

Note: Remember that this is the class list at the end of the academic year, meaning that both Karl and Franz completed the academic year successfully.

The idea of a six-year-old boy from a farming village being sent off to a high school whose language of instruction was Latin is quite incredible, but we have to accept this. The normal age of children in the lowest classes seems to have been between 10 and 14.

But the parish register is quite clear that Franz Theodor was born in 1763. The attendance records of the Jesuit high school in Brünn show a 'Franciscus Schuberth' attending for one year as Rudimentista in 1769. The arithmetic of nine minus three equals six cannot be refuted. Was Franz Theodor an extremely clever and precocious boy, unlike the common portrayal of him as the mindless, low-level drudge who fathered and held back a genius? It seems possible. Given his later work-ethic and conscientious application as a teacher there can be little doubt that he would have been a dedicated learner as a child.

But, as a farmer's clever son, he only had two reasonable escape routes open to him, the church or schoolteaching. The former would have required celibacy, which, considering his baby-making abilities within and without of his marriage, would probably not have been a happy state for him. Even had he been another Kant or Hegel, the options open to him resulting from his social class would have been the same. But why he went there at six years old is inexplicable.

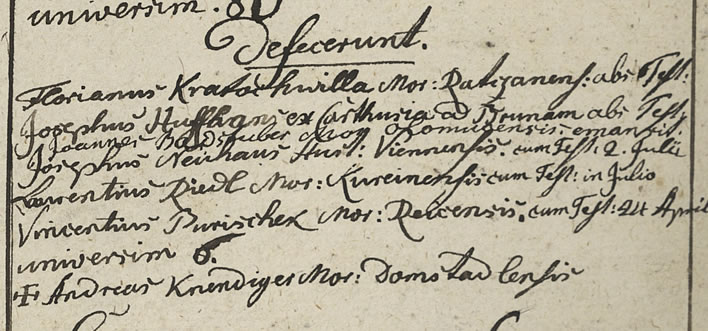

Franz Theodor's gap years

As we have noted, for some reason we do not know, Franz Theodor had a three year break after completing his first year. It has been surmised that he broke off his schooling because he was too young and out of his depth. This statement is, however, difficult to prove: he formally completed his first year and I know of no record that states he was unable or unqualified to start his second year. The Jesuit high school listed the pupils who broke off their studies – with or without testimonial – or who were thrown out or who died. Franz Theodor was not one of these. When he came back as an 11-year-old his first year was credited, so that year must have been regarded as an academic success.

Anyone who did not complete a year successfully was listed at the end of the class list under the rubric defecerunt 'those withdrawn/fallen through' with a brief reason. The absence of Franz from this list is more evidence that the six year-old completed the first year successfully. Those who think that Franz Theodor, the father of the composer, was some kind of intellectually limited shadow in the blaze of his son's genius have to acknowledge the talent and application Franz Theodor shows in completing this tough year at such an early age.

We can only assume that he returned home and spent three years on the farm with his family and continued at Becker's school in Hohenseibersdorf. He was still young and so the three 'lost' years were not as important as they would have been to his older brother Karl, who was already 14 when he started at Brünn.

Karl continues

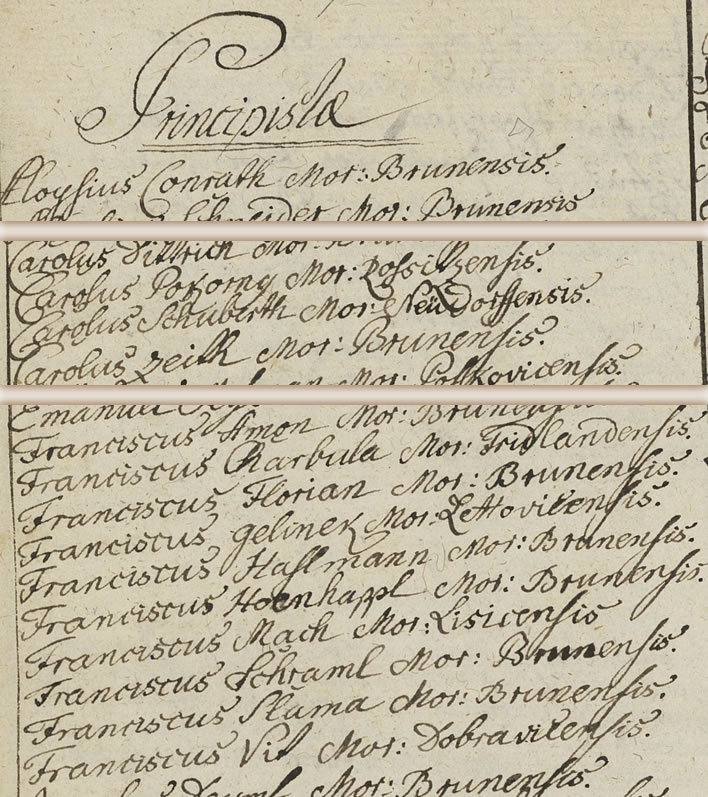

After the first year Karl's education proceeded in an orderly manner, although without his brother.

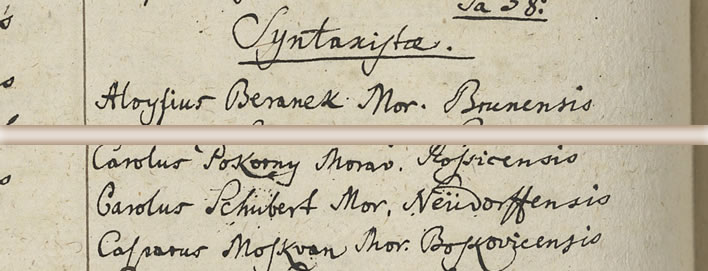

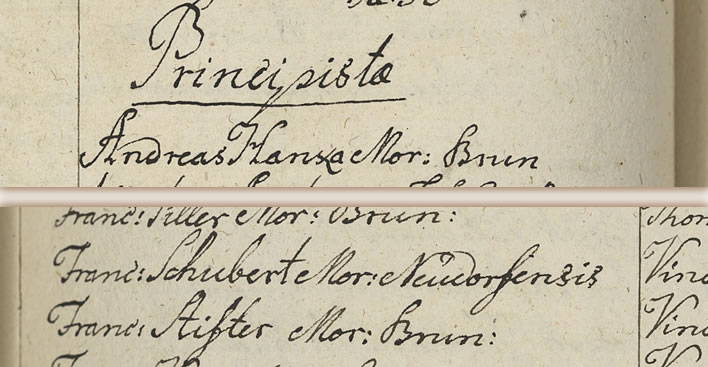

The school year 1770-71. Karl's name is there among the Principistae who completed the second class. There is however no trace of Franz Theodor. His name is not among the defecerunt for that year, implying that he never even started it, that is he stayed home in Neudorf.

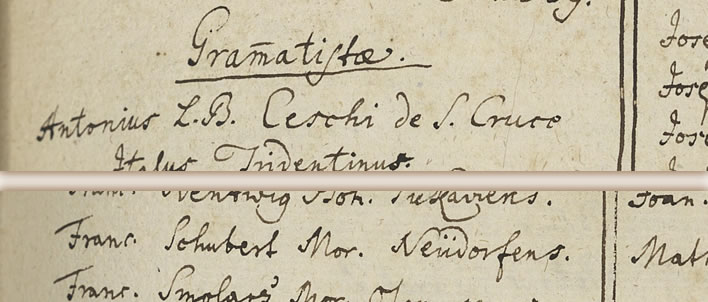

The school year 1771-72. Karl has completed the third class Grammatices.

The school year 1772-73. Karl has completed the fourth class Syntaxeos.

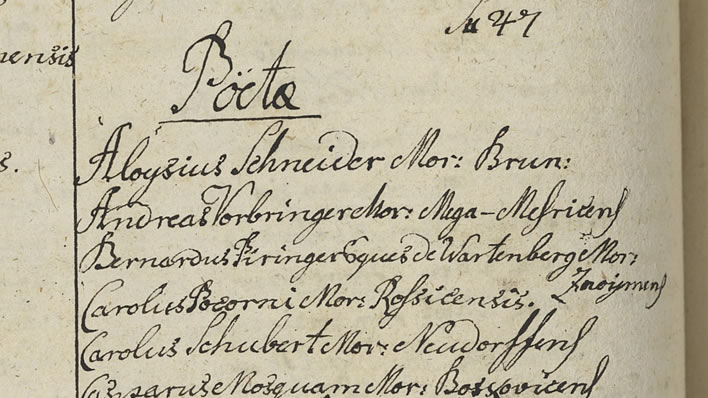

The school year 1773-74. Karl has completed the fifth class Poeseos…

Franz Theodor goes back to school

After his three year break, Franz Theodor returned to the school in 1773 and picked up where he had left off.

…and his brother Franz Theodor returned to the school in 1773 and has now completed the second year, the Principiorum. He is continuing his schooling where he left off three years before.

The school year 1774-75. Karl Schubert has completed his final year Rhetorices…

…and his brother Franz Theodor has completed his third year, the Grammatices.

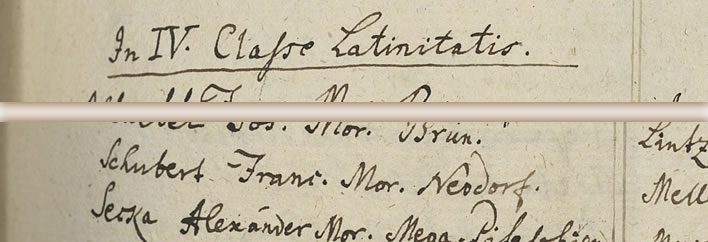

The school year 1775-76. Franz Theodor has completed his fourth year in the renamed class Latinitatis. In 1773 the Jesuits were formally banned as an order, leaving the Austrian educational system, which had so relied on them, in disarray. However, as we can see in the records for Brünn, for a long time little changed – the teachers were still Jesuits and the curriculum was still the Jesuit curriculum. One of the first changes was to reduce the length of the course from six to five years, which is why we now have to cope with some confusion and with changing class names.

Note: Pupils are now listed alphabetically under their surnames, another sign of the changes taking place in the educational system.

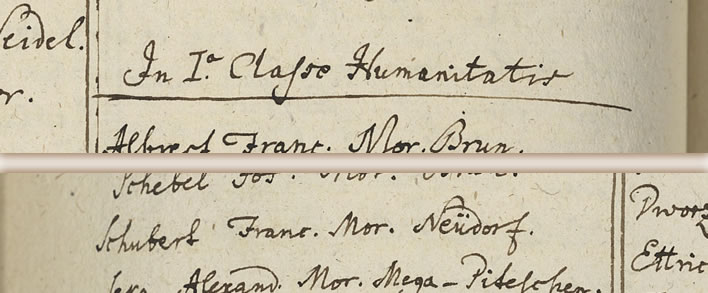

The school year 1776-77. Franz Theodor has completed his fifth year in the renamed class Humanitatis.

The school year 1777-78. Franz Theodor has completed his sixth year in the new top class Poeseos.

Note 1: The school lists are now more expansive, each row taking the full width of the page and the age of the pupil is added.

Note 2: The compiler of the list has given Franz Theodor's age as 22. He was born in 1763, which would make him 15 or 16 in 1778. We shall return to this age entry in a short while.

Just for some context, we note that the Schubert brothers were not the first boys from Neudorf to go to the Jesuit High School around this time. Franz Bihrendt (1747-?) completed a full six years there from 1762 to 1767. He was followed three years later by Anton Schubert (1752-?) who attended the school for the full six years from 1765 to 1770. Anton was the cousin of the brothers, the son of Carl's brother Johann (1712-1763). He was in his last year there when Karl and Franz Theodor arrived.

Two boys from Hohenseibersdorf also went to Brünn together, Karl Lengsfeld (1754-?) and Hieronymous Reinelt (1753-?), from 1768-73. They were in their third year when the Schuberts arrived.

The Jesuit High School in Brünn was therefore not an unknown institution for the brothers, other boys from the area had gone before them. There were other village boys there at the same time so their schooling was not, at least initially, a lonely experience.

For the greater glory of God

For the beginning of their schooling the brothers would certainly have needed Becker's instruction: the entrance requirements of the Jesuitengymnasium were strict and demanded knowledge for which a simple village school could not prepare them:

No boy will be enrolled who is not already able to write German and Latin legibly and who has not mastered declination, conjugation and the fourteen rules.[2]

What kind of an education did Karl and Franz get? A tough one. The mission of Jesuit schools was to teach the subjects in such a way that the pupils were

brought to an understanding and love of the Saviour and that everything they do is for the greater glory of God –'ut proficiant ad majorem Dei gloriam'.[3]

At the top of every page that pupils wrote they were to print 'AMDG', a reminder to them of the purpose of their efforts on that page.

A modern child would find the Jesuit education as it was taught in Brünn at that time a bitter pill. In Jesuit schools the main intellectual task was considered to be 'the best possible acquisition of the Latin language in both spoken and written form', being 'the language of the Church and the Christian heritage' in which 'the treasures of the knowledge of all times and all people are contained'.

Not only was Latin one of the main objects of study, it was also the language of instruction in all classes, even the lowest. Fortunately for the Schubert boys, the Jesuits had been forced by imperial decree in 1735 and 1752 to teach German in at least the first four years of study.

Greek, the language of the renaissance and the enlightenment, was taught grudgingly. The Church Fathers wrote in Latin. Because Greek had never been part of traditional education it was difficult to find Jesuits who could teach it. One teacher in Brünn who taught Greek there in 1764 admitted later that he himself was only a lesson ahead of his pupils.

The teaching method in the Gymnasium was rote learning rather than the thoughtful production of original work. The process was reinforced by encouraging a competitive spirit among the boys. They were required to perform dramas and public recitations. There were too few teachers for the large number of pupils and so senior pupils were coopted into the work of repeating drills with the younger boys.

The religious observances, processions and feast days (each class had its own patron saint) and the preparation and execution of the many competitive presentations and dramas gobbled up teaching time: out of an eleven month school year less than half the time, only 180 days, was truly educational in any sense that we would understand the term.

The curriculum and methods may strike us now as absurd, but the Jesuit education was well regarded at the time as a preparation for a life in the priesthood or among the many cogs of the extensive bureaucracy of the Hapsburg empire. Quite a few Moravian aristocrats had been schooled in Brünn.

Far from being the low-level, small-minded farmer's son that some biographers have described, Franz Theodor had an extensive and thorough education, an education in which he performed exceptionally well: he started this tough education at an extremely early age – at least three years earlier than usual. He may not have had a creative brain – who knows? – but it is certain that he had an excellent memory and a marked ability to apply himself.

He was grateful enough for this education to give his first two children the name Ignaz, from St. Ignatius Loyola, the founder of Society of Jesus.

References

- ^ All images of the registers for the Jesuitengymnasium in Brünn are reproduced with the permission of the Archiv der Stadt Brünn, Fonds N 46 – Deutsches Staatsgymnasium, Comeniusplatz, Brünn 1630 –1944, Inventarnummer 5866 (Archiv města Brna, fond N 46 – Německé státní gymnázium, Komenského náměstí, Brno 1630–1944, inv. č. 5866).

- ^ Ratio atque institutio studiorum S.J. (1735), quoted in Geschichte des Deutschen Staats-Ober-Gymnasiums in Brünn: von der Gründung desselben im Jahre 1578 bis zum Jahre 1878., 'Geschichte des Gymnasiums', Carl Friedrich Dittrich p. 13.

- ^ Ibid. p. 13.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!