The cradle of the Habsburgs

Richard Law, UTC 2016-07-07 12:10

Is that it?

… or some variant of it, is the puzzled reaction, day in, day out, of the fans of historical monuments who turn up at the Habsburg Castle in Switzerland. They have probably already ticked off Schloss Neuschwanstein, mad Ludwig's fairytale erection in Bavaria, Sanssouci in Postsdam and many of the other great castles and fortresses built down the centuries by the lovely megalomaniacs of Europe.

Habsburg? The home of the greatest European dynasty, one that bestrode the continent for eight centuries? That's it?

There's a small castle on a small hill in a little-known area of Switzerland. There's a restaurant and a few ragged foundations on the hilltop. Yes, that is it.

At first glance just a rather nondescript building with a tower next to it and a terrace with restaurant tables.

A little more elevation and we can see the ruins of the original Habsburg castle hidden in the surrounding trees.

That's the short answer. The long answer takes us back a thousand years in the region that is now southern Germany, eastern France and northern Switzerland.

The land of milk and honey

The building of the Habsburg castle was begun sometime shortly after 1020, a moment that falls within a dramatic period in European history. The two centuries between 1050 and 1250 (warning: very fuzzy dates – there will be a lot of them in this post) saw huge changes in Europe. That period spans most of what we now call the Medieval Warm Period of climate (950-1250), a period that seems to have been very congenial to human life and culture during which Europeans emerged from the cold 'Dark Ages' to enjoy two centuries of generally clement weather.

It doesn't surprise us, therefore, to learn that in these two centuries there was a dramatic growth in population throughout Europe: it is estimated that the population tripled in that period. Warmth is a great blessing: more infants survived, famine was rare and a warm and well-nourished population survived the diseases that in colder, hungrier times slaughtered them in great numbers. We can truly speak of this period as a breakthrough time for civilisation in Europe.

An extensive deforestation took place in these times: with immense manual effort trees were felled, stumps dragged up, roots hacked out and new agricultural land laid out that could feed a growing population. Deforestation had been going on through the previous centuries, but it is fair to say that at the beginning of this period a visitor would have found huge forests dotted with patches of agriculture, whereas two centuries later there is a landscape not very different from our own, or more accurately from what it was at the beginning of the 19th century, a landscape with many hamlets and small towns surrounded by cultivated fields.

Farming efficiency increased as the amount of cultivated land was extended. When agriculture moved beyond offering mere survival for those who lived on the land, farmers and landowners had time to be creative. New implements were invented, particularly ploughs, and new systems of cultivation introduced. We can assume that the growing population was the motor that drove agriculture to new productivity, but population growth could just as much have been the result of a reduction in food scarcity. It makes no difference: both trends went hand in hand. At the end of this period we can speak without hyperbole of a land 'flowing with milk and honey'.

In those two centuries the region of Alsace in eastern France, for example, the ancestral home of the Habsburgs, went from being a countryside of dense forests and aristocratic hunting to becoming one of the principal wine growing regions of Europe. Alsace is stretched along the warm rift valley through which the Rhine flows northwards from Basel. Today the region is known as the 'Garden of France', a garden which originated in the two centuries we are discussing.

It was not just agriculture that flourished. This was also the great period of the foundation of towns that went hand in hand with the new prosperity of the countryside. Farmers gained large markets for their produce; the growth of the new towns and the concentration of the population in them was predicated upon an agricultural system that could keep them alive.

As agriculture and the towns prospered so did all the trades: metalwork, textile production, silver-mining and so on. As wealth increased so did the quantity of money in circulation and the level of consumption. Those two centuries were a wonderful time for trade, local and pan-European, and for people with commercial acumen and strategic vision: the Habsburgs.

The dynasty emerges

Where did the Habsburgs come from? There are so many speculative genaeologies in existence that an answer to that question is not straightforward. If we peer through the historical fog for reliable sources and not just will o' the wisps we can make out the origins of the Habsburgs in the noble Etichonid family in Alsace.

'Who?', the exasperated reader cries.

Ignorance here can be readily forgiven. In the normal course of events dynasties crumble and vanish when failures in breeding lead to the end of the male line. In the case of the Etichonid dynasty the cause of its collapse is more unusual. The head of the house, Albrecht II von Dagsburg had done his dynastic duty and ended up with two sons, Heinrich and Wilhelm – the classic 'heir and a spare'. However, they were both killed in 1202 in a tournament in Andain (now called Saint-Hubert) in present-day Belgium. Few people nowadays know of the family and now we know the reason why.

A branch line of the family, starting with a certain Guntram the Rich (sometime in the 900s, his dates so uncertain that I am not going to propagate the guesses), married its way up the Rhine, in the course of two generations establishing itself in Lower Alsace (now France), in Breisgau (now Germany) and finally in Altenburg (now a part of Brugg), a former Roman fortress in a rich and strategically important area of what is now the Canton of Aargau in northern Switzerland. Using the walls of the Roman castrum in Altenburg Guntram's son Lanzelin built their first base there.

The Eigenamt

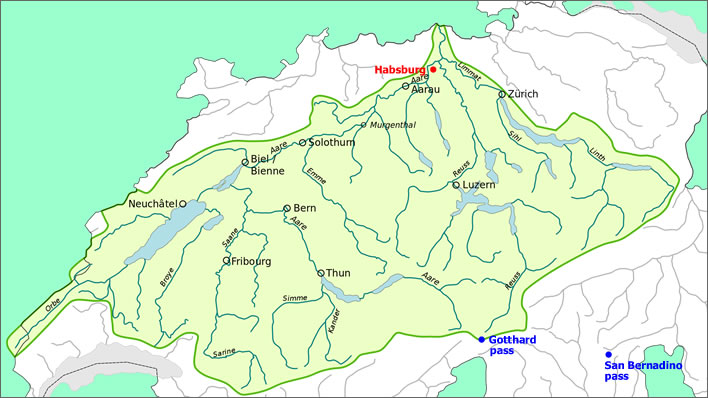

This Habsburg touchdown is in an area at the apex of three navigable rivers: the Aare, the Reuss and the Limmat. The Aare is the largest river in Switzerland, connected with the present-day capital Bern and the western, French-speaking regions; the Ruess tumbles down all the way from the Gotthard region in the central Alps; the Limmat flows out from the Lake of Zurich, which in turn is fed by the rivers from the mountains of the Grisons in the eastern Alps. The Reuss and the Limmat flow into the Aare, which then, swollen with these tributaries, flows on for about 20 km until it joins the Rhine at Koblenz in Switzerland.

The accumulated waters of the now great river Rhine then flow west for a few kilometres more to Basel, make a sharp turn right there into the fertile rift valley of Alsace and then flow down the length of Germany, through the Netherlands and into the North Sea.

The three great river systems that drain nearly all of Switzerland: the Aare (left), the Reuss (middle) and the Limmat (right). Having picked up its two great tributaries the Aare flows northwards to meet the Rhine (not shown), that flows here east to west along the Swiss border. The Habsburg castle is situated almost exactly at the junction of the three rivers. For international traffic the route to the Gotthard pass is much shorter than the routes to its competitors in the east, such as the San Bernadino pass. Image: Wikimedia.

Thus, from the viewpoint of communications and trade, three of the five largest rivers in Switzerland and their accompanying trade routes come together in the middle of the Habsburg territory and then join up with the Rhine, one of the great communications axes of Europe, barely 12 km further on.

The region was still densely forested at the beginning of the period in question and the great trade routes through it were on, alongside or near the rivers. The Aare, further upstream, also formed the borders between the territories along its banks and was therefore a politically important communication route. The very important east-west route between Zürich and Basel also crossed the middle of Habsburg territory.

A couple of kilometres from Altenburg is a hill that rises steeply about 160 m above the plain of the Aare and the Ruess. Here, beginning around 1020, Radbot, the grandson of Guntram, erected a castle he named the 'Habsburg'. The 'hab' relates to the ford and mooring place on the river and so means 'the castle of the ford'. The bridges, fords and moorings in this region were of considerable commercial importance – duties could be raised on all goods passing through. There is a fanciful etymology that derives the name 'Habsburg' from the confected word Habichtsburg, meaning the 'castle of the hawk', but this suggestion is just that: fanciful.

An aerial view showing the later, much restored buildings that now house a restaurant and a small museum. The ruins on the right are the remains of the early buildings of the castle. The remarkable thickness of the walls can be seen – nearly two metres: the thickest walls in any comparable building from this time throughout the region. Radbot and his successors built to last; unfortunately, it didn't.

Eighty or so years later, around 1108, Otto II, Radbot's grandson, took the name of the family castle as his title of nobility, styling himself 'Count von Habsburg'. [As it happens, the last Habsburg to have any titular connection with the Austrian Empire was also an Otto, Otto von Habsburg (1912–2011), closing a meaningless but nevertheless trivially interesting 800 year circle.] The name of this little castle was thus attached to the great dynasty-to-be.

This triangle of land where the Aare meets the Reuss became a single territory the Habsburgs called the Eigenamt– their 'own jurisdiction'.

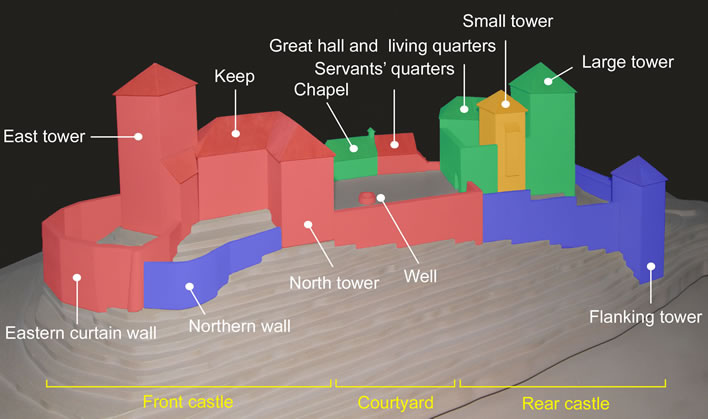

A reconstruction of the castle. Only the green and yellow sections are still standing today. The red sections and the yellow tower were built before 1100; the blue and green sections were built between 1100 and 1250, the large tower, the 'palace', possibly later. Image: Micha L. Rieser.

A view from the eastern end of the castle looking across the ruins towards the restaurant. The thickness of the walls is impressive: could there have been a lot of stone available that had been dressed by the Romans a thousand years before? One empire builds upon an older one. Image: Tage Olsin.

The right place at the right time

Whether their acquisition and development of the Eigenamt was a considered strategy or just good luck we do not know. If the former, it was a brilliant one, if the latter, they were very lucky indeed.

For if you were given a map of Switzerland showing only the basic topography and waterways and were asked to stick a pin into the most commercially strategic spot in the country, the Eigenamt would be an obvious and excellent choice. Surrounded by forests, then later rich agriculture and vinyards, sitting on the great communications axes of central Europe, the location of the Habsburg territory was the first step of the dynasty towards its domination of Europe down the subsequent centuries.

The great land and river routes – east-west, north-south and alpine transit – knot together here in Habsburg territory, giving the dynasty considerable income from customs duties as well as political dominance in the region. As a centre of trade their territory also benefited from that more general enrichment that we have already discussed that took place through most of Europe at that time: the astonishing growth of population, the acceleration of deforestation, the growth of agriculture and urban development, hamlets and settlements expanding into villages and new towns. During the 1200s alone nearly 100 towns and villages were founded along the route of the Aare between the Rhine and Geneva. Towns mean trade.

Rivers, bridges and fords

River crossings were often just fords, one of which, as we know, gave its name to the Habsburg castle and eventually its dynasty. Bridge building was expensive and initially only undertaken by towns in favourable positions: Basel, Rheinfelden and Brugg ('bridge'). These bridges could be financed by customs duties and tolls.

The income the Habsburgs received from the customs duties levied on the transit traffic was twice as much as all the other customs duties they received and at least the equal, sometimes more, of the taxes they were able to levy on all the towns in their territory.

Rivers were used mainly to transport goods downstream, particularly heavy goods such as casks of wine from Burgundy and the wine growing regions of west Switzerland. Logs from the forests of central Switzerland were floated down the river system, sometimes as far as the North Sea. Sailing along a river was free of charge – who could stop you? – but mooring and landing places attracted duties, especially those where goods were transferred from water to land transport.

Towing laden boats upstream was expensive and only justified for high value goods, so, for example, in the upstream direction the principal source of customs income was the transport of salt from the saltworks of the Rhine, Salzburg and Bavaria. Salt was an expensive essential: small amounts fetched high prices and were worth the cost of transport.

The importance of river traffic during this time can hardly be overstated. Zurzach, situated on the Rhine near the confluence of the Aare, Reuss and Limmat – only about 15 km from the Habsburg castle – became firstly an important destination for pilgrims and then developed into a remarkable trading post on a European scale, purely by virtue of its riverside position and its taxfree mooring places. The modern 'Laffer curve', which shows how total income increases as the tax rate falls, applied then as it does now: Zurzach held huge markets in the spring and the autumn that were visited by sellers and buyers from all over Europe.

The great Gotthard route

But there were more specific advantages to the siting of the Eigenamt. Around 1200 the Gotthard pass became a viable and popular alpine crossing between the North of Europe and the rich northern Italian plains. Up until then the difficulties of the deep and frightening gorges on the northern approach had been a great deterrent, but pathways, plank traverses that creaked and bent under you and bridges were built. There were astonishing, for the time technically brilliant bridges such as the Teufelsbrücke, the 'Devil's Bridge'. Despite all the terrors, the transit traffic boomed.

The first opening of the Gotthard route was effected by building trackways along the sides of the cliff face, the most famous of these was the Twärrenbrücke, which was used until 1707. We have no certainty about the structure of these trackways: it is assumed that they were wooden walkways running along the cliff face over iron rods driven laterally into the rock and held up at the outer edge by chains fastened into the rock above. As with all the structures in the Schöllenen gorge, the Twärrenbrücke seems to have been damaged and repaired several times. It was finally replaced in 1709 by a 64 m tunnel blasted through the rock – the first ever Alpine road tunnel – on 15 August 1708.

However hair-raising this route through the Schöllenen gorge was – it made a deep impression on Goethe during his passage across the alps in 1779 – it was worth it. The maximum altitude was not only around 500 m lower than the old Gotthard track, meaning that the season it could be used was longer, but the transit time was reduced by about three hours, a vital saving for a convoy of people and pack animals. Overnight stops were easier to plan and less exposed to alpine weather.

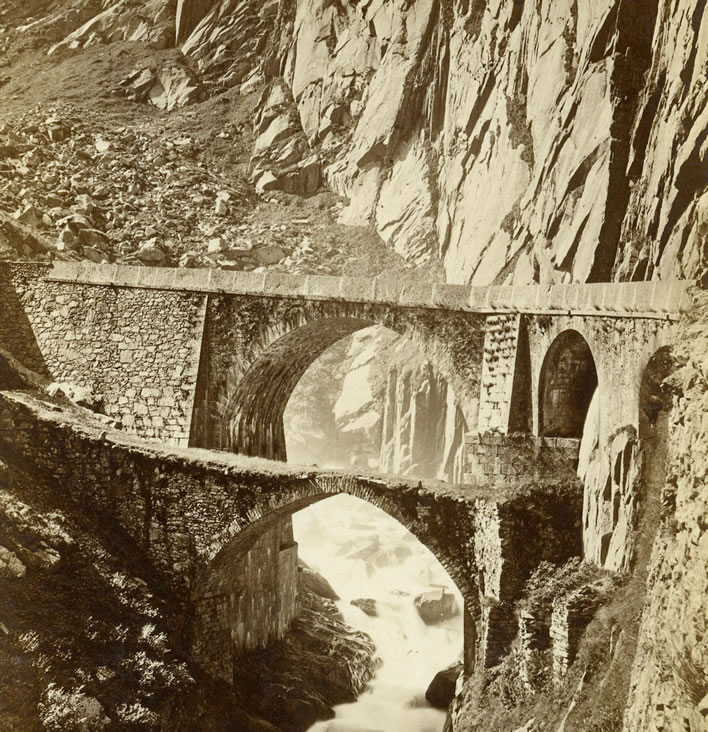

The first bridge over the Reuss in the Schöllenen gorge was a wooden bridge built in 1230. It was damaged and rebuilt several times before being replaced by the 'first' Teufelsbrücke in 1595. This bridge was also damaged and repaired several times until it was replaced by the 'second' bridge in 1830, after which it was no longer used and left to ruin. It finally collapsed into the river on 2 August 1888.

The damage to mountain bridges is not just due to torrential water but the impact of boulders brought down by the flood.

This early postcard photograph (date unknown) shows the first bridge still standing and the second bridge behind it. The first bridge had no guard rails or parapets: crossing it was not for the faint-hearted. Some remnants of the exposed track to the bridge can still be seen below the new path. Several other, less challenging bridges were built, too. In general the Gotthard bridges were between about 2.5 m and 3 m wide, just sufficient for two loaded pack animals to pass each other.

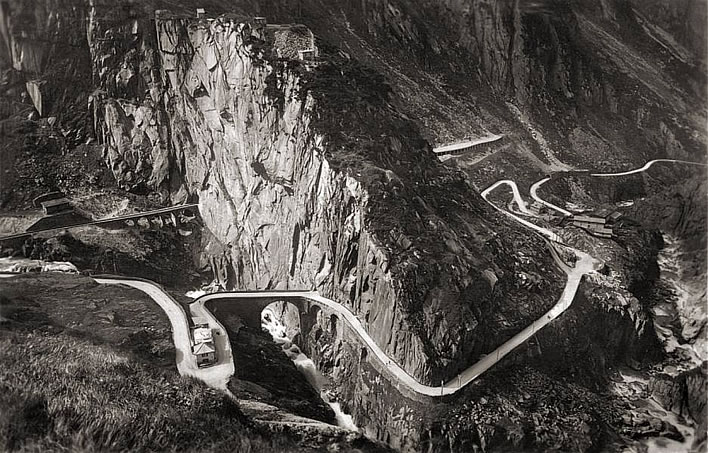

The second Teufelsbrücke seen from the air in 1934. The first bridge had collapsed in 1888 and the third bridge would not be built until 1958. The railway bridge can be seen behind the road bridge. Image: Artur Wyss-Niederer.

The second Teufelsbrücke is in the foreground. Through the arch of the bridge on the left can be seen the remains of the base of the first bridge. The third Teufelsbrücke runs across the background and into the tunnel. It was built in 1958 to cope with the increased motor vehicle traffic on the route. The photograph is taken from the railway bridge. Image: Marcin Wichary

A modern image (2011) illustrating well the steep terrain of the Schöllenen gorge. Image: Хрюша.

In a short space of time the Gotthard route became a serious competitor to the ancient but longer routes that ran through the Grisons and across the eastern Alps. A little later the Gotthard overtook the old eastern routes to become the dominant alpine pass, despite the efforts in the east of Switzerland to draw traffic back to the eastern passes.

The Habsburgers profited in two ways: not only were they located at the foot of this route in north Switzerland but they also had territories in its upper reaches. Friedrich von Schiller (1759-1805), in his now world-famous play Wilhelm Tell (1804) described the unrest among the Swiss over the Habsburg commercial stranglehold on the region [Act 2, Scene 1, ll. 874-878]:

His [the Habsburg king] are the markets, the legal courts, his

the trade routes and even the packhorse

that crosses the Gotthard, has to pay his toll.

From his lands as it were with a net

we are wrapped around and locked in.

Looking after the investment

Schiller's Swiss grumblers, groaning under the yoke of the Habsburgs, conveniently leave one aspect unmentioned: the need for a central authority to ensure the upkeep and safety of these routes. The upkeep of such routes – the word 'roads' would give a misleading impression of these waggon tracks – however 'international' they might be in their overall length and traffic, was the responsibility of each domain and each village through whose territory they passed. Left to themselves, locals had little interest in maintaining at great effort tracks that they themselves barely used. The upkeep of the routes had to be done as part of the feudal labour service that the peasants owed to the local landowner. The more time was spent in road maintenance, the less time was available for agriculture. The effort was rarely in the interest of landowners either. It therefore took a regional power such as the Habsburgs, with their strategic viewpoint and their feudal dominance, to insist that this maintenance be carried out.

The Habsburgs also offered protection from robbers on the route and compensation should travellers be robbed, a worthwhile benefit for traders passing through wild territories in wild times.

The dynasty took care of the routes in its possession: they were important investments. For example, the east-west route between Zürich and Basel was important and much frequented. Apart form its local importance it was part of the great transit axis between Italy and Germany that crossed the Septimer and San Bernadino passes.

The Bözberg Pass

The great routes were only as good as their weakest link. An important 'pass' was, for example, the route over the Bözberg in the neighbourhood of the Habsburg castle. It cut the corner from the Aare to the broad Rhine valley leading to Basel.

The Bözberg is a hill that rises scarcely 200 metres above the surrounding countryside – nowadays we hardly notice this hummock: the motorway tunnels under it; driving over it is effortless; even the effort of riding a bike on the modern, metalled roads over it is minimal. But then it was an appreciable obstacle for the transport of goods in ox-carts. We moderns may now hold the distance saved to be trivial, but when pack and draught animals had to be fed and quartered, saving a day by cutting a corner was welcome and worth a reasonable toll.

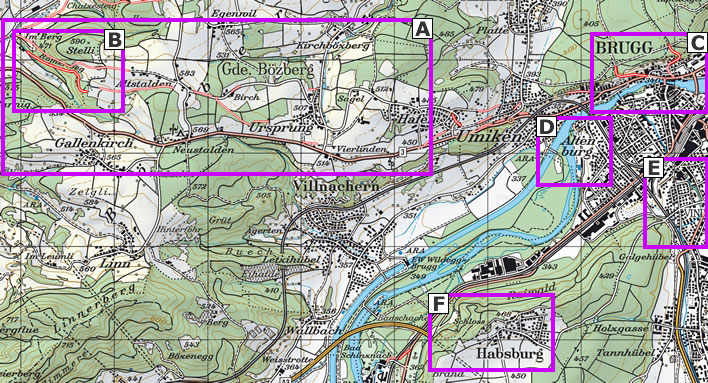

The Habsburg locality in the modern context.

A–The pass over the Bözberg.

B–The Römerstrasse, site of the excavations described below.

C–Brugg, the town founded by the Habsburgs (charter from Rudolf I).

D–Altenburg, the first touchdown point for the Habsburgs in the region.

E–Part of the Roman town Vindonissa.

F–Habsburg Castle (left) and the village (right).

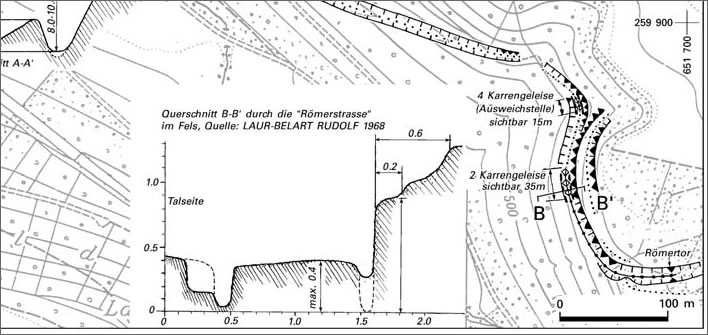

Remains of the deep cutting where the pass over the Bözberg descends towards Effingen. All images in this section are from the Inventar historischer Verkehrswege der Schweiz, Kanton Aargau, website.

The remains of a limestone cart track on the Bözberg Pass, probably dating from about 1350. This section of track is exposed for a distance of about 35 m. The grooves for the wheels are about a metre apart. The stone on the uphill side of the track has been cut back to provide clearance for the axle hubs of the carts. Steps have been cut into the stone to provide humans and animals with a good footing.

The remains of a passing place on the limestone cart track on the Bözberg Pass. The main track is on the right; the side track can be seen on the left. Steps have also been cut into the track. This section of track is exposed for a distance of about 15 m.

Excavation plan of the sections of the Bözberg cart track shown above. Similar stone tracks have been discovered in other places on the Bözberg Pass, some at at depth of 0.5 m under the soil. It is assumed that the Romans had similar tracks over the Bözberg.

The Römertor ('Romans' Gate') is a 10 m long cutting through a stone outcrop on the Bözberg Pass. The cutting is around 3.5 m deep and around 2.5 m wide.

In the hands of the Habsburgs the track over the Bözberg was maintained: their customs income along the other parts of the route depended on it. However, when the Habsburgs withdrew and left their castle and their routes under the control of Bern, who lacked the Habsburg's broad, strategic horizon and their skill at the hands-on control of their possessions, the route fell into disrepair. By 1750 the Bözberg route was effectively a ruin that goods traffic avoided, accepting the inconvenience of the extra distance required to get round it. Bern only woke up to the problem when it realised how much money it was losing because of the collapse of customs income.

The Romans were here

The Habsburgs were not the first to see the strategic and tactical advantages of this location: the Romans were there a millenium before them. The forts and settlements of their empire were clustered here; a line of barracks, watchtowers, settlements and fortifications –Vindonissa, the castrum at Altenburg, Augusta Raurica– running along the south of the Rhine that faced the barbarous German hordes to the north and formed the nexus with the great Roman roads that went south to Italy (home!) or south west, following the great curve of the river Aare to the Roman cities of west Switzerland –Aventicum, Genava– and then west into France. For a long time this was a frontier of the Roman Empire. And that, we recall, was another period of clement weather – the Roman Warm Period – and an associated great cultural flowering.

Guntram, the founder, and Radbot, the castle builder, may have known nothing of these mysterious remains among the forests and river meadows of this land. After about 400 AD the Roman settlements along the Rhine were abandoned and their meaning passed out of the mind of man and into stories told to children before a fire. Through six hundred years of dereliction the houses, streets, forums and amphitheatres were just a useful source of stone – for the East Tower of the Habsburg Castle, one of its earliest structures, elements of Roman buildings were used that were plundered from the ruins of Vindonissa. The earth, debris and the loam of five hundred autumns gradually covered the rest. The manuscripts that documented the life of this civilisation disappeared into the darkness and were only recovered and read many centuries later. The Roman Empire was largely forgotten. Aventicum, the greatest city in Roman Switzerland, was only fully rediscovered around the beginning of the nineteenth century.

Attractive though the conceit may be, the idea of the 'new' Holy Roman Emperors building their castles on the ground of the 'old' Roman Emperors probably never occurred to the Habsburgs, but the coincidence does tell us how strategically valuable this area was.

However, in Wilhelm Tell Schiller mentions that coincidence of the remains of the old civilisation lying under the new civilisation during his account of the murder of King Albrecht von Habsburg [Act 5, Scene 1, ll. 2974-2978]:

There where the prince rode over a farmer's field

– under which an ancient city from heathen times is supposed to lie –

facing the old fortress of the Habsburg

out of which his family's power arose

The 'farmer's field' is in a town now called Windisch, which the Romans knew as Vindonissa, a military camp with thermal springs and amphitheatre. After a century of excavation more of it is still being found, even today.

Rudolf, the founder of the dynasty

Everything came together for the Habsburgs and they made the most of their luck. They picked up the pieces from the collapse of the male lines in other once-great families in what is now south-western Germany: the Zähringer line failed in 1218 just as it was on the brink of becoming a great dynasty in Germany and its pieces were scooped up by the House of Kyburg, which itself collapsed scarcely 50 years later in 1264 when its male line failed. The Kyburg possessions were in turn grasped by Count Rudolf IV von Habsburg (1218-1291), six beneficial generations on from Radbot, the castle builder. The acquisition was effected by a mixture of force, political cunning and opportunism that was completely characteristic for Rudolf, who would become the great Emperor Rudolf I, the Habsburger who lifted his dynasty onto the European stage.

The Habsburgs were loyal allies of the great Staufer family and did what Habsburgs have always done best: made profitable marriage alliances. When the Staufer dynasty collapsed in 1268 the Habsburgs were the great beneficiaries.

Rudolf was a remarkable man. His chroniclers list his characteristics: unusually tall, slim, moderate in his consumption, wise and clever and with a serious expression but affable and capable of humour. His piety set a standard with which almost all later Habsburg rulers would associate themselves. That piety seems to have been a personal piety – about the Church and its organizations he was less troubled, being quite capable of taking sides against the Pope and of burning abbeys to the ground when necessary.

He possessed an excellent strategic and tactical military brain, was functionally violent in a violent age, yet without mindless rage – he usually preferred to integrate his vanquished enemies into his rule rather than vengefully stamp them into the ground. He had no compunction in chopping off the feet of those who resisted him, though.

Altogether, not a man to be trifled with. Following some ruthless early victories his reputation as a military leader was such that, in a number of later conflicts, his mere presence would be enough to ensure a rapid resolution before a sword needed to be drawn.

He avoided set-piece battles: for the military strategist in him their outcomes would be just too unpredictable. He was certainly averse to courtly, tournament-style engagements. Instead he approached difficulties with a masterful mixture of political and military understanding, seasoned with tactical innovation.

Rudolf, whom we presume could himself neither read nor write, nevertheless understood the importance of good administration. It secured and maintained rights and legal obligations but above all led to the maximisation of income and good financial management. Whilst other houses were squandering their incomes or just losing money through inefficient management of their assets, Rudolph was increasing and stabilising his finances. That good administration meant that he was always in a financial position to acquire territory or feudal rights when the opportunity arose.

He was a restless and driven character, ceaselessly acquiring territory for his dynasty and also, after his election as Emperor, fighting or mediating one conflict after another. He was able to master the interlocking puzzle of the many noble families of the time, their interrelationships and the tangle of feudal rights and obligations that arose from them. For nearly 20 years as Emperor he was almost continually in the saddle, criss-crossing the Empire on imperial and family business. Grant such a man a long medieval lifetime of 73 years and things happen.

He was elected the first Habsburg King of the Romans in 1273, becoming King Rudolf I, the preliminary to becoming Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. In itself, the role of king was not powerful, it was, however, a valuable tool for the increase of dynastic power. Should the dynastic succession of a family fail, the emperor had the right to redistribute the remains, inevitably giving preference to his own relatives and allies. Dynastic marriages were also easier to arrange and manage. The Habsburgs were able to acquire dynastic titles such as Duke of Austria and Count of Tyrol. These became family assets.

Every family, not just the Habsburgs, did this whenever they became emperors: the Luxemburgs became kings of Bohemia (a part of the empire), the Wittelsbachs expanded in what is now Bavaria and elsewhere. The Habsburgs, in the end much longer on the throne, did it better than everyone else and after a while the imperial title became theirs de facto. A time came when no one questioned anymore whether the Prince-Electors should choose a Habsburg. In all, the Habsburg family supplied twenty of the emperors or kings in German history.

Austria becomes Habsburg

Almost immediately after his election Rudolf was faced with a moment of great danger that could have put an end to all the Habsburg dynastic ambitions. Had he failed that challenge, the House of Habsburg would be for us just a footnote in obscure history books. In the election of 1273, the ambitious King Ottokar of Bohemia had expected to be elected King of the Romans. Unlike this Habsburg newcomer he was at least a proper king.

The Prince-Electors thought otherwise and chose Rudolf von Habsburg. Ottokar did not accept the decision to choose this upstart from the west. Rudolf, as the new king, had a duty to defend his election and with it the legal entity of the Empire. Earthly legal obligations could always be trumped by victory in battle, in which the hand of God had chosen the outcome directly.

After some preliminary skirmishing the two gave battle in 1278 on the Marchfeld, about 40 km to the north west of Vienna. Rudolf's political and military skill throughout the conflict so far had been exemplary and his reward came in this remarkable battle: Ottokar was slain, his body relatively respectfully displayed in Vienna for all to see – that there should be no doubt (imposters and conspiracy theories are not a recent invention) – and it was Ottokar who became the historical footnote. There was some tut-tutting and pursed lips from the purists of courtly battle at Rudolf's methods and particularly the slaying of Ottokar, but, in the end Rudolf had won by God's grace and that was that.

Rudolf, his kingship now soundly validated by divine will, gained for his house among other things the duchies of Austria, Styria and Carpathia. In 1282 he installed two sons as Austrian Dukes. Above all, unlike his other territories – whether as Habsburger dynast or Emperor – the territories aquired from Ottokar came in two great blocks.

Rudolf received the papal approbation shortly after his election and so became the first Habsburg Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He was never crowned, though, for in the course of the twenty years Rudolf lived after becoming King and despite his desire to get that important bauble on his head he and the Pope – much troubled by unrest in Italy – could neither find a date for the coronation nor the money to finance it.

Rudolf was elected head of an empire that was falling apart when he took over. After the death of the last German emperor, Friedrich II in 1250, three weak non-German Emperors, concentrating on their own difficulties, let the affairs of the empire slide. As emperors they were so ineffective that the 23 year period until Rudolph's election in 1273 is called the 'interregnum', as though no emperor existed in this time.

It was a time of lawlessness and partial anarchy. Some feudal lords took the opportunity to appropriate property to themselves, land and properties that really belonged to the Empire. Rudolph, focused and decisive, won back nearly all of the territories that had been lost. Not only did he see off the challenge of Ottokar of Bohemia he restored the authority of the Holy Roman Empire in central Europe. As we have already noted, disputes seemed to resolve themselves when the tall figure of Rudolf entered the room.

Rudolf also used those twenty years as King of the Romans to the great advantage of the family. Relatives were placed in offices of the state and the family spread its roots deep into the imperial administration. By the time of his death in 1291 he had brought the Habsburgs to a position of great power and influence: sons had been produced and the family had jumped from being regional nobility to being a German dynasty. His predecessors remain misty outlines to us, thus leaving him the true founding father of a dynasty that would survive in power from then until 1918, almost 650 years.

Emperor Rudolf I's gravestone in Speyer Cathedral in Germany. Contemporaries thought it a remarkable likeness of the man himself, made at a time when such images were normally idealised figures. Tall and imposing, serious and pious, the image fits in with contemporary accounts of his personality.

The fall of the castle of Habsburg

The small castle in Switzerland whose name the Habsburgs bore had already been left behind long before this. After the acquisition of the properties they gained from the collapse of the Zähringer family in 1218 the Habsburgs had outgrown their castle on the hill. Rudolf was born in the same year in Sasbach (now 'am Kaiserstuhl'), not in the Swiss Habsburg castle, which he later inherited, but had no particular attachment to it other than its name.

When Radbot had built the Habsburg around 1020 he had been in the castle-building avant-garde. From then until about 1250 it seemed that everyone who was anyone was building a castle. They were popping up all over Europe.

Two centuries later the opposite was true. The nobles of Europe were moving out of their hilltop strongholds and into palaces and town houses in the towns. In this movement the Habsburgs were also ahead of the game. After those two centuries of occupation and extension the small castle in Switzerland no longer fitted the modern lifestyle of a great medieval family. The area was securely in their hands so the inconveniences and deprivations of the draughty fortress lifestyle on top of a small hill were no longer necessary.

And finally, but very importantly, the character of war itself had changed. Courtly conflict – the feudal 'feud' – rarely involved laying siege to the opponent's castle. More usually it consisted in laying waste his serfs' farms, crops and livestock – and killing his serfs too, if they were foolish enough not to flee in time: soft targets and peasant oiks of no consequence. In military terms, therefore, castles were not much use, apart from allowing you a good view of your enemy stealing and destroying your property down in the valley.

Around 1220, two centuries after Radbot had started building the castle from which they took their name, the Habsburgs moved their base to more comfortable and fitting quarters in the nearby town of Brugg and spent their time in more amenable accommodation in their other territories in south-west Germany, Alsace and Austria.

They sloughed their little family castle off like a cocoon, stretched open their wings and fluttered off to richer meadows. As their empire extended they occupied distant palaces in Austria, Germany and Italy. Emperor Rudolf had not been born there and he chose to die and be buried in Speyer, 200 km north of Habsburg castle. Their imperial horizon of the Habsburgs already extended far beyond the little castle on the small hilltop in now troublesome Switzerland.

Switzerland had seized independence and was lost to the Habsburgs. The tapestry of possessions they called Vorderösterreich, 'Further Austria', hinged around the old territories along the Rhine that had made up their path from Alsace to the Eigenamt such as Freiburg, Waldshut, Rheinfelden; all these went when Napoleon flipped up the chessboard of Habsburg Europe. For us moderns they are now just parts of southern Germany.

In the course of the centuries after the Habsburgs themselves no longer lived there the castle changed hands repeatedly and fell into nearly total ruin. All traces of the hated Habsburgs were left to crumble; the castle was cannibalised for building materials. The parts we see today were 'renovated' in 1559, the old parts were levelled to the ground in 1680. There followed more ruin and then more 'renovation' in 1866 involving a new top floor and roof on the large tower, the interior of which was 'renewed' in 1947. The archaeologists arrived in 1978.

At this point we have to do what we so often do on this blog: we have to point out that you can go to the castle and have a nice lunch and be accosted by someone in a mock medieval costume but don't expect to find the Habsburgs. They haven't been there for seven centuries. Apart from the ruins of the walls, they would themselves hardly recognize anything here. And the Swiss flag would certainly ruin their lunch.

Just when, after pointlessly pondering so many meaningless stones, your mind is wandering towards a swift gin and tonic, a charming serving wench appears with a plate of dried apple-rings. We are told that Rudolf I only visited the Habsburg once, in 1256, preferring to stay in the family's residence in Brugg. Understandable.

The neglect is not surprising: most Swiss had never loved the dynasty and would be at war with them on and off for more than 200 years after Rudolf I's death. The last thing anyone in Switzerland wanted was a monument to the Habsburgs on their territory.

Out of a desire for historical accuracy we have to qualify that last assertion a little. Not all Swiss were or are anti-Habsburg. The caprices of history have left a corridor of Catholic and Habsburger sentiment on the Swiss border along the Rhine between Basel and Waldshut, in what used to be the lands that Guntram the Rich traversed all those years ago, the lands that eventually became Vorderösterreich and which Franz II/I let go in 1806. Even the Catholicism of the area has a special flavour that right up to the present day invokes Joseph II as its founder. Let us leave that troubling image of Joseph II as the founder of a Catholic sect and move on.

Over time the surrounding forests were cleared and a tiny hamlet – a few houses – grew up in the shadow of the ruined castle. A few parts of the castle remain and have been restored: they currently contain a restaurant with some museum displays attached. That curse of modern life, the museum curator, has also infested the ruins, bringing informative panels, sound and light displays and all the other designer apparatus needed to 'bring the site into the 21st century'. The flag of the Swiss Confederation flutters over the stones, possibly the worst insult of all.

How are the mighty Habsburgs fallen, or, as Schiller put it in Wilhelm Tell, possibly thinking of all the traces of the long gone empire of the Romans on which the Habsburgs built [Act 4, Scene 2, ll. 2426-7]:

The old collapses, the times are changing,

And new life flowers in the ruins.

That's it?

Yes, that's it.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!