The Jacobin Conspiracy

Richard Law, UTC 2016-10-01 09:00

Closing Austria down

In our piece Franz's belljar last month we noted that the Austrian Emperor Franz II (1768-1835), rattled by the progress of the revolution in France and the fear of imitators in the Empire, brought back Count Johann von Pergen (1725-1814) from retirement to be his Minister of Police.

From the spring of 1793 Pergen took over the control of the police and Franz's own interventions in security affairs became fewer. It would be wrong to say that Franz now relaxed his grip on security: Franz never relaxed his grip on anything: he was too fearful to take such risks and too arrogant to think that other people could do their job without him. But in the person of Pergen Franz had found a like mind, a fellow repressive who now had all the power he needed to carry out his task in complete secrecy, effectively without any legal constraints.

The monitoring and censorship of books and newspapers were relatively straightforward administrative tasks. Keeping foreigners, especially diplomats, under observation was also a straightforward – though tedious and expensive – task. Listening for careless, drunken talk in taverns was also an easy matter, especially since everyone knew that the government was doing this and so loose talk became self-suppressing. Even so, some incautious people were slow learners.

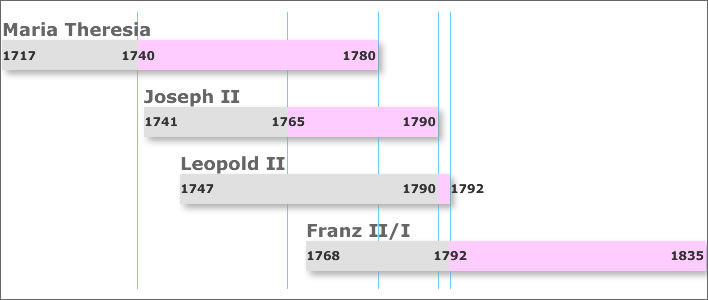

Quick guide to Austrian rulers

Your cut-out-and-keep guide to Austrian rulers from Maria Theresia to Franz II/I. The regnal period is coloured in lilac. The overlap between Maria Theresia and Joseph II is the period of the co-regency, starting after the death of Maria Theresia 's husband and ending with her death. Joseph's hectic mismanagement begins when he becomes sole ruler upon his mother's death and it lasts the remaining ten years of his madcap reign. Joseph and Leopold were sons of Maria Theresia. Franz was the son of Leopold. Franz II relinquished the title of Holy Roman Emperor in 1806 and continued to rule as Franz I, Emperor of Austria. He is now usually referred to as Franz II/I. Image @FoS

The disappointed class

In addition to these three sources of annoyance there was also a large group of bitterly disappointed intellectuals, frustrated civil servants and academics in Austria, many in positions of power and influence. Joseph II (1741-1790) has to bear most of the responsibility for their disappointment. He pinned the enlightenment badge on his uniform and thus got the thinking classes excited, but his defects of character – his impatience, arrogance, egotism, bitterness and sarcasm – were such that he was never able to fulfil the hopes his supporters had for him.

His successor, Leopold II (1747-1792), had been forced by the dangerous unrest his brother's failures had left behind to spend his brief time on the Austrian throne annulling Joseph's madcap measures and trying to bring the ship of Empire back on an even keel. In many ways he was genuinely more 'enlightened' than his noisy brother, but was much subtler in his actions. He kept the malcontents at arm's length, watched them and even encouraged the production of 'enlightened' pamphlets when it deniably suited him. He danced a gavotte with his hotheads.

Leopold's dance became more energetic in the months just before his death. He was firmly of the opinion that constitutional change was necessary and that such change had to be preemptive. Concessions wrung out of governments through unrest only led to more unrest and demands for greater concessions. In the spirit of gradualism that had served him so well as Archduke of Tuscany, Leopold began work again on his constitution for Tuscany. His plans had been interrupted when he became Emperor in 1790.

A constitution for the heterogeneous Empire, with so many different countries, languages and social forms would be a political Eiger North Face. His brother Joseph had rushed at that towering challenge in his madcap piecemeal way and had come a cropper on the first rope. At the time of his death he was twisting helplessly above the abyss – and the future of the Empire with him. In contrast, the homogeneous Tuscany, which Leopold knew so well, where he was so respected and where he enjoyed a reputation that extended far beyond its borders as the model of the contemporary enlightened prince – that was a completely realistic ascent. Get that working well and you would have a starting point and model for the rest.

The first year of Leopold's reign had been spent disentangling Joseph's ropes: almost all traces of that rash ascent were taken down. In the second year it was time to do the job properly, the Leopoldine way. In the furtherance of this end there was much informal discussion and preliminary paperwork in those months with those he regarded as useful to him or sound on constitutional issues, people such as Sonnenfels, Leopold's 'house teacher' Andreas Riedel and – puzzlingly – the strange Hungarian and proto-Bolshevik, Ignaz Joseph Martinovics (1755-1795). Behind the closed imperial doors an intellectual gavotte was quietly in progress.

Franz takes over

Leopold II died after a two-year reign. With his son, Franz II, the intellectual gavotte stopped. Franz had served in Leopold's government and knew exactly what was going on, but lacked the self-confidence and flexibility to play Leopold's Italianate game himself. There was not a transition period: to say that Franz changed things overnight would be an exaggeration, but not a great one.

Franz himself – even during his uncle Joseph's reign – had argued for preemptive reform, particularly in respect of Belgium and Hungary. But at that time he had been sitting in the row behind Joseph and Leopold: the timid, hesitant and stubborn young man could afford to be brave. When they had gone he was left alone, all eyes on him as France sank into bloody anarchy. Franz would hear nothing of constitutional reform, even preemptive. Uncle Joseph had shown where that led: to uproar and chaos. Throughout his reign Franz would have nothing to do with constitutions, effectively banning the use of the word in his presence. His dying words would be: 'Change nothing'.

Many of the enlightened ones suddenly lost jobs and influence with the Emperor, the only person who mattered in the Empire. Some stayed loyal to their monarch and did their patriotic duty in an empire now at war; many went loyally silent and got on with their lives, whatever disappointment they might have felt at the course of events; some remained active and tried to influence Franz from the sidelines. But the Emperor was unmoveable. He was infamously stubborn, as he noted himself once when talking about the lack of success his former teachers had in getting him to do things he did not want to do.

Franz had served his apprenticeship under Joseph and was an important figure in Leopold's administration. He knew all of the enlightened butterflies who fluttered around the courts of his uncle and his father. He knew them well, and knew how dangerous some of them could be. They formed a political opposition that soon gave up trying to influence him and turned to thinking of ways to remove him, with or without his head attached. They became the soil in which the Austrian Jacobins germinated.

The fate of one man is a symbol for the dramatic rapidity of the changes that Franz brought in after Leopold's death: Franz Gotthardi (1750-1795). He had been appointed Police Director in Pest, Hungary, by Joseph II, charged with the organization of the secret police informers there. He came to Vienna and was employed as the Administrative Director of the Viennese National Theatre. This position was just a cover for his activities as the leader of Leopold's secret spying organization. On Franz's accession he was retired. He had recruited a number of important spies for Leopold and it seems that his closeness to these now dubious figures was his downfall, for only two years later, in 1795, he was rounded up in the sweep for Jacobins, tried and sentenced to 35 years dungeon incarceration. He died aged 45 in prison of tuberculosis a few months after the verdict.

But what could our would-be revolutionaries do in practical terms? Franz II/I knew exactly what he was doing when he tightened up censorship, strengthened the secret police and took measures against masonic lodges and any other suspect meetings almost immediately after his accession. He thus closed down all the open channels of communication and discourse in the empire. All oppositional political activities were forced underground. Of course, Franz's repressive measures intended to silence public criticism and opposition made it more difficult for him to keep track of the now secret goings on in his empire – but for that he had Pergen and his men.

Organizing revolution

For the malcontents every act of dissent was difficult and risky. Serious discussion and debate were hardly possible and therefore no serious and coherent policy or programme of action could be developed. It was effectively impossible to have anything even slightly critical printed. It was dangerous to write down lists of participants, minutes of meetings, resolutions or any of the paperwork necessary for political discussion. The propagation of ideas was strangled. Handwritten texts were copied and passed from hand to hand.

There was an attempt to make common cause with the repressed – the farmers on the land and the lower orders in the towns – using folksy literary forms such as songs, short satires, prayers and sermons. It is believed that a large number of such works circulated from hand to hand, but in a huge geographically, linguistically and socially disparate empire this effort had practically no effect as far as we now can tell.

The rural poor may groan under the impositions of their landlords, but they were mostly also averse to change, as Joseph had discovered to his cost when he tried to reform feudal servitude in one characteristically Josephinian sweep of the hand and found that many of those he thought he was helping preferred the existing arrangement to his new-fangled ideas. Changing the religious establishment was also fraught with difficulty, as Joseph had also found out with his attempted ban on religious idolatry. The deep piety of regions such as the Tyrol would not allow any modernisation of the relationship between church and state.

The problem, one that we might consider to be the fundamental revolutionary problem, that of getting the support of the people you are trying to help is an old one. It was faced by the Austrian Jacobins as much as it would be faced in so many revolutions since then. The would-be revolutionaries in Britain under Lord Liverpool's repressive government after the Napoleonic wars had exactly the same problem:

The Major in particular warned them of the necessity of drill; and plainly told them also that, not only were the middle classes all against them, but their own class was hostile. This was perfectly true, although it was a truth so unpleasant that he had to endure some very strong language, and even hints of treason. No wonder: for it is undoubtedly very bitter to be obliged to believe that the men whom we want to help do not themselves wish to be helped. To work hard for those who will thank us, to head a majority against oppressors, is a brave thing; but far more honour is due to the Maitlands, Caillauds, Colemans, and others of that stamp who strove for thirty years from the outbreak of the French revolution onwards not merely to rend the chains of the prisoners, but had to achieve the more difficult task of convincing them that they would be happier if they were free. These heroes are forgotten, or nearly so. Who remembers the poor creatures who met in the early mornings on the Lancashire moors or were shot by the yeomanry?[1]

Since all publications had to be anonymous no unifying figure could arise around whom the revolting masses could unite. This Austrian opposition was totally amorphous: no individuals or groups could put their heads above the revolutionary parapet without running the risk of physically losing them. Austria was at the start of what would be nearly 20 years of war against France and by implication against the new order there. Opposition to authority in such a time now offended many people's innate patriotism and easily veered into becoming treason.

Building a political movement required recruitment, but this was extremely risky in Franz's police state, in which every recruit, however well-known, however trusted, could turn out to be the spy in your midst. And so it would be eventually with the Austrian Jacobins.

References

-

^

Mark Rutherford [Hale White (1831-1913)], The Revolution in Tanner's Lane, Trubner and Co., London, 1887, p. 110. Online

White is describing the meetings that led up to the march of the 'Blanketeers' in 1817. The march was dispersed violently and its leaders imprisoned. The legacy of fear left behind by the anarchy of the French Revolution – a reactionary Zeitgeist– was felt by all European governments. This quotation is included to indicate that Franz II/I and Pergen were not alone in their repressive measures and the Austrian Jacobins not alone in their plotting.

Bibliography

The following works form a solid introduction to the subject of the Jacobin Conspiracy. The current article is intended for a general readership and in general only direct quotations are referenced.

- Drimmel, Heinrich. Kaiser Franz : ein Wiener übersteht Napoleon. Wien : Amalthea, 1981.

- Körner, Alfred. 'Andreas Riedel : ein politisches Schicksal im Zeitalter der Französischen Revolution'. Diss. Köln : Kleikamp, 1969.

- —. ‘Der österreichische Jakobiner Franz Hebenstreit von Streitenfeld’. Jahrbuch des Instituts für Deutsche Geschichte 3 (1974): p. 73.

- — and Franzjosef Schuh. Die Wiener Jakobiner. Deutsche revolutionäre Demokraten. Vol. 3. Stuttgart : Metzler, 1972.

- Pichler, Caroline. Denkwürdigkeiten aus meinem Leben. Ed. Emil Karl Blümml. 5,6. München : G. Müller, 1914.

- Reinalter, Helmut. ‘Baron Andreas Riedel als Staatsgefangener in Kufstein’. Veröffentlichungen des Tiroler Landesmuseums Ferdinandeum 56 (1976): 117–127.

- —. Der Jakobinismus in Mitteleuropa : eine Einführung. Vol. 326. Stuttgart : Kohlhammer, 1981. Kohlhammer-Urban-Taschenbücher.

- —. ‘Die Jakobiner von Wien’. Die Zeit, 8 December 2005.

- Schuh, Franzjosef. ‘Hebenstreits Gedicht »Homo hominibus«’. Österreichische Philosophie zur Zeit der Revolution und Restauration (1750-1820), Verdrängter Humanismus - verzögerte Aufklärung. Band 2. Wien : Turia & Kant, 1992. 775–800.

- Wangermann, Ernst. From Joseph II to the Jacobin Trials : Government Policy and Public Opinion in the Habsburg Dominions in the Period of the French Revolution. Oxford Historical Series, 2nd Series. London : [s.n.], 1959.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!