Deutschland, Deutschland über alles

Richard Law, UTC 2017-01-09 08:43 Updated on UTC 2017-02-14

Our readers – those rare, furtive creatures, insomniacs all – have come to realise that our oft-repeated motto, 'things are almost never as they seem', usually signals that they are in for a long slog, a lonely trudge that starts with the 'two o'clock in the morning courage' of which Napoleon spoke before finally ending at the first glimmer of light in the east.

Well, the motto has much truth: things are almost never as they seem. For another example of this universal truth let's take the Österreichische Kaiserhymnen, the 'Austrian Imperial Hymn'. Throughout its history of transformations – 220 years this month – it has hardly ever been what it seemed to be. You may even need to have a pencil and paper handy to get through this one.

A world at war

The work arose in the winter of 1796/7. The preceding seven years had been an almost continuous horror for the Austrian Emperor, Franz II/I. The French Revolution had started in 1789 and its worst terror had lasted until 1794. The crowned heads, princelings and gentry across the rest of Europe had an understandable fear that they might very well be next – the click of Madame Defarge's needles troubled their sleep. Franz's father, the gifted and prudent Leopold II (1747-1792), had died in 1792 after a reign of only two years, leaving his timorous son, just turned 24, to guide the Austrian Empire through these difficult times.

Franz was too timid to introduce the reforms that might have saved the Empire. He had seen at first-hand the mess that his know-it-all uncle Joseph II (1741-1790) had got into by playing around with all this 'Enlightenment' nonsense. He must have known that he did not have the talent for the Italianate scheming at which his father, Leopold II, had been so good.

His response to the danger was the introduction of a repressive police and censorship system. He was reinforced in his repressive instincts by the seditious plots that were discovered, most notably the 'Jacobin Conspiracy' in 1794. His father had been playing these hotheads skilfully, allowing them to confide in him and to report on their fellow travellers. Given the company he kept and all the things he knew, we are not surprised to learn that Leopold had a 'nervous stomach'.

Franz, when he came to power, would have no truck with this devious nonsense: his newly formed secret police fished the hotheads out of their murky ponds and he sent them off to dungeons, ropes and blocks.

In the meantime Napoleon had brought some order back to France, but the 'War of the First Coalition', which Austria and Prussia had foolishly triggered in 1792, would rumble on until autumn 1797. Five years of war, death, cripples and deprivation, without much for either side to show for it.

Praising the Emperor

In all this gloom what the Empire needed was a rousing anthem. Britain had God Save the King/Queen, France La Marseillaise. Franz's 29th birthday would take place on 12 February 1797 and an anthem would be created for him as a present.

The text was written by Lorenz Leopold Haschka (1749–1827). Who? you exclaim. Quite. Haschka is known today only to specialists with time on their hands – to the rest of us he is a blank and, quite frankly, deservedly so. At the time he could be considered to be the court poet of the Habsburgs, a safe pair of hands when you needed an ode in a lofty style to celebrate something or other or merely express outrage at the French.

No absolutist ruler was ever upset by hyperbolic praise. The successful court poet needs to have a shameless insincerity, a non-existent gag-reflex and, above all, to have no fear of exclamation marks:

Gott erhalte Franz, den Kaiser,

Unsern guten Kaiser Franz!

Lange lebe Franz, der Kaiser,

In des Glückes hellstem Glanz!

Ihm erblühen Lorbeerreiser,

Wo er geht, zum Ehrenkranz!

Gott erhalte Franz, den Kaiser,

Unsern guten Kaiser Franz!

... etc.

God preserve Franz the Emperor,

Our good Emperor Franz!

Long live Franz the Emperor

In the brightest splendor of Fortune!

May laurel branches bloom for him,

Wherever he goes, as a garland of honour.

God preserve Franz the Emperor,

Our good Emperor Franz!

... etc.

It takes a strong stomach to read this, let alone sing it. You don't really want the other three verses, do you?

The first thing attentive readers will notice is that this is not a 'national' anthem. It is a hymn of praise to a specific person occupying by God's grace the throne of Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. A similar thing could be said of the British 'national' anthem.

Unlike his father Leopold II, who was a constitutional enthusiast in the same way that others play with model trains, Franz II/I detested all forms of constitutional nationalism and even banned the use of the word 'constitution' in his hearing, a position he would maintain until his death in 1835. The text is therefore not about 'Austria' or even the Holy Roman Empire: it is directly addressed to him, the emperor by divine right.

The statement famously attributed to Louis XIV, l'état, c'est moi, 'I am the state', could be applied just as easily to the Austrian Habsburg emperors. Joseph II had indeed described himself the 'first servant of the state', but this was just another of the fantasies that rattled so dangerously around inside Joseph's erratic, 'enlightened' head and which nearly lost the Habsburgs their empire. When he needed to be, Joseph was as autocratic and despotic as the rest of them, his nephew Franz II/I included.

Kaiser Franz II, c. 1795–1799, around the time of his birthday present, by Johann Baptist Lampi the Elder (1751–1830). Image: ArtNet.

Haydn hits the mark

On their own, Haschka's lines are not going to lift anyone out of their seats. In order to do that they needed to be set to music. For that job only one person came into question: Joseph Haydn (1732–1809). We are told that it was Franz Josef Count Saurau (1760-1832) – attentive readers will recall that he was one of the leading lights in the prosecution of the Jacobin conspirators – who suggested Haydn for the job. It doesn't really matter, since Haydn was really the man to go to for composing to order: he had spent 30 years of a life of restless productivity doing this for the Esterházys.

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) by Thomas Hardy (1757–1804), 1791. Image: Royal College of Music.

The anthem was performed on Franz II's birthday, 12 February 1797, in all the theatres of Vienna. The birthday boy himself was present in the Burgtheater and expressed his satisfaction at this barrage of sycophantic praise.

The birthday present hit the mark with the public despite Haschka's text and become popular as a default national anthem: Count Saurau's instinct had been correct. This meant that for the next century or so until the whole imperial edifice collapsed, at every change of ruler the verses had to be reconstructed around the name of each new Emperor.

The great survivor was Haydn's music, which even outlived the destruction of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918 to continue as the national anthem of the Republic of Austria until 1938. Haydn's music was simply too good to waste on Haschka's execrable text. Haydn himself used the melody in 1797 in his Cmajor String Quartet, op. 76 Nr. 3. The second movement consists of three variations of the Imperial Hymn, causing the work to be given the title 'Emperor Quartet'.

The religious natures reading this will associate the tune with John Newton's (1725-1807) Olney Hymn, 'Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken' (first published in 1779, the year before Maria Theresia died. At some point the hymn was sung to Haydn's melody, now called 'Austria' by the British. Once the pixie-dust of Haydn's melody settled on it, it became one of the most popular of Newton's hymns.

Their new anthem may have cheered the Austrians up and helped bear them through another 15 dark years of Napoleonic wars, deprivations and financial crises, but it really annoyed the Germans.

Reinventing Germany

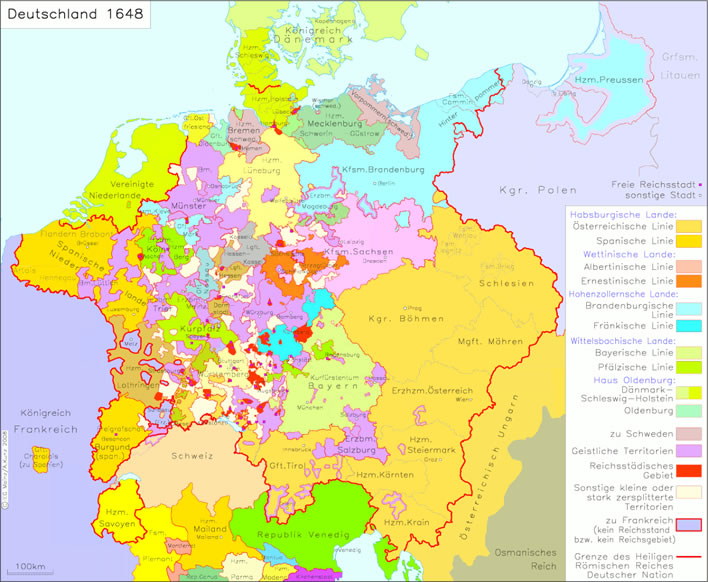

What Germans? you ask – because, of course, there wasn't a 'Germany'. The Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 had divided what we would now think of as 'Germany' into a patchwork quilt of small states, a patchwork so complex that it requires a large book and a constitutional lawyer's mind to describe the status and forms of government found within it. Each of the patches had its own religious and political identity, but as time went on the feeling of an underlying, shared German identity became stronger and stronger.

Map of the European patchwork that came into being after the conclusion of the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. Image: IEG-Maps, Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte Mainz, ISSN 1614-6352.

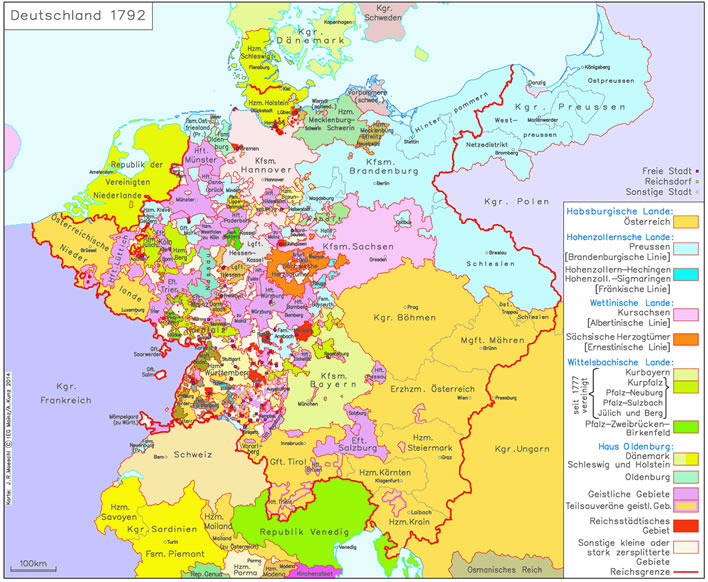

Map of the European patchwork in 1792. This is the year of the accession of Franz II to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. If anything, the fragmentation of the Germanic states is even worse than it was in 1648. We note, however, the new extent of Prussia, including particularly the presence of Schlesien, Silesia, which Prussia 'acquired' from Austria during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). Image: IEG-Maps, ibid.

Despite major dialect variations there was a common language. Where there was a common language there was a common culture, too. This 'German' culture is impossible to define with precision. It is easier to understand in terms of what it was not. It was not the culture of the Bourbon French with their complex mannerisms and affectations, their much vaunted language of diplomacy, of civilisation and culture. It was not the culture of the Austrian Empire with its multi-lingual, multi-cultural complexity and prevailing Catholicism. German culture embraced Catholicism and Protestantism equally.

The blossoming of German writing in the 18th-century contributed enormously to this feeling of shared identity: Herder, Wieland, Goethe, Schiller, Rückert, Heine and so on and so forth. The sheet of paper for that list of names would have to be a long one. The hundred years between 1750 and 1850 are filled with talented German writers and philosophers whose work transcended the political patchwork. It could only be a matter of time before the political structure was adapted to the cultural structure. By 1800, the midpoint of this German century, when Napoleon was deconstructing the old order, German minds turned to the longing for a German nation.

We have to be fair and point out that there were some writers – such as the later Heine – who came to think that the mythmaking of the 'Goethe-cult' was actually a distraction from the true political problems of the time, the repressive regimes throughout Europe and not just in the putative German state. On that subject Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels contemporaneously had a lot to say. Neither the nationalist nor the communist solution turned out well. We point it out and move on: nothing is as it seems, it seems.

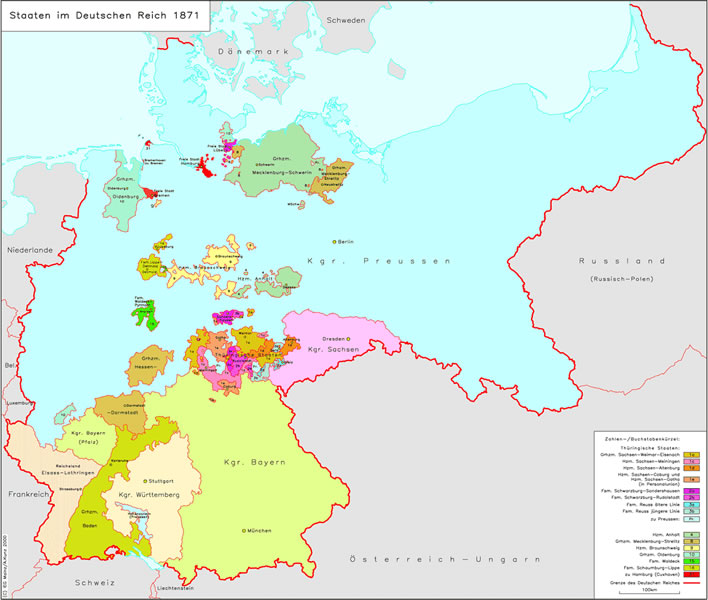

Napoleon trampled over the Westphalian patchwork more or less at will. The Austrian Empire could not stop him and, apart from Prussia, the German patches were too fragmented to have any effect. It would take until 1871 before political union took place and we can speak of 'Deutschland'.

Well, we nod sagely, we can understand that the presence of the French jackboot might arouse feelings of German nationalism in the occupied territories, but, in fact, the effect was counter-intuitively much stronger.

The French had had their revolution and wherever Napoleon set down his boot they marked their territory by introducing their anti-aristocratic civil rights: astonishing things such as equality before the law, freedom of religion and open court procedings – all those things that made the feudal families that were still dominant in Germanic countries tremble in their boots. Even censorship was lifted and for a while writers could actually write freely – as long as their sentiments weren't anti-French, of course. When the Napoleonic dominance of Europe started to collapse after 1812, the aristocrats scuttled back out of the woodwork and all the civil rights were revoked and the old order reinstated. The old adage is always true: if you want to make your people deeply unhappy, even mutinous, give them something, then take it back.

After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Franz II/I's Foreign Minister, Prince Metternich, coordinated in the interests of peace and 'calm' in Europe the 'restoration' of German politics as it had been before the French Revolution. The period from 1815 until the great but ultimately failed revolution of 1848 was a period of coordinated repression and censorship across almost all of the German patches in the quilt.

Kaiser Franz II/I von Österreich (1768-1835), Friedrich von Amerling (1803–1887), 1832. 35 years on the throne leave their traces. Image: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien.

Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben

During this time in the minds of the German patriots the Haschka/Haydn anthem was an expression of the imperial, Habsburg dominance of Metternich over that patchwork of German-speaking territories. To Haydn's music several alternative, Republican versions appeared, some parodies. Haydn's tune was simply too good not to be re-used, whatever the context. We don't have time or energy to go into all the variants that appeared.

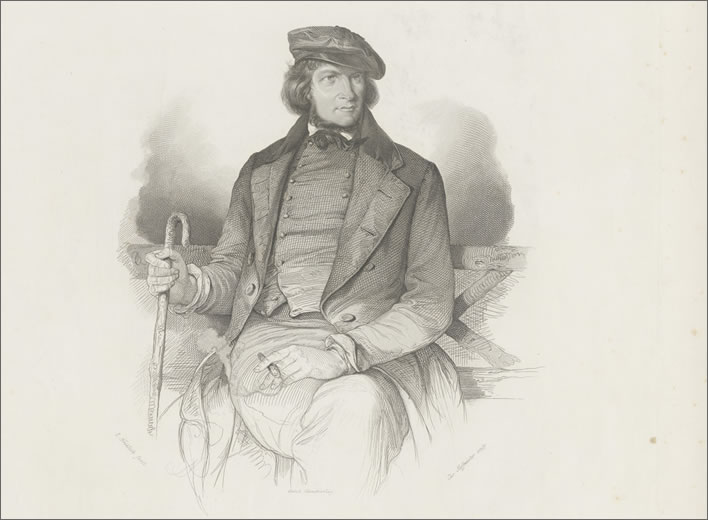

One person, however, was fixated on that tune, a German, August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben (1798-1874). We note the interesting but pretty irrelevant fact that he was born a year after Schubert and the birth of the Haydn anthem.

August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben. Steel engraving by Christian Hoffmeister (1818–1871), after a painting by Ernst Fröhlich (1810-1882). Image: Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

The young Hoffmann (he added on the 'von Fallersleben' himself to distinguish himself from the many other Heinrich Hoffmanns of the time) had a promising career: by 1835 he had become a full professor for German Literature in Breslau. However, you cannot keep a good hotheaded malcontent down, however much you promote him. In 1840 and 1841 he published two volumes of verse ironically titled Unpolitische Lieder, 'Unpolitical Songs', 290 poems altogether, which became an instant bestseller. The poems were so 'unpolitical' that Hoffmann was stripped of his professorship and pension in 1842, shortly after their publication, and expelled from Prussia the following year. Their author was gone, but many thousands of his books were still on the shelves of the populace.

Hoffmann went into a seven-year exile, wandering restlessly around Germany. He is certainly a contender for the record for the most expelled person of the age: he was expelled 39 times during this period, even from the town of his birth. The tale of his wanderings during his exile would fill this article to overflowing – those who might like to spend some time zig-zagging around modern Germany will find many buildings bearing plaques of the type 'Hoffmann von Fallersleben lived/slept/hid here'.

If you ever need an example of the old motto 'the pen is mightier than the sword' then you only need to consider the intensity of the persecution of Hoffmann, poet and Professor of German. We are considering a time when being a 'patriot' branded you as a dangerous subversive.

His fate during these years is yet one more symbol of the Austro-German belljar of repression that Franz II/I and the Counts Pergen and Saurau started around the time of the birth of the Haydn/Hatschka hymn – Saurau was the hymn's midwife so to speak – and the international projection of that belljar by Metternich.

What does that mean, 'international projection'. Well, there had been a time when someone such as that persecuted journalist and poet Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart (1739-1791), the author of Die Forelle, made famous by Schubert, could dodge from patch to patch on the quilt to escape his tormentors. In 1777 he found himself for a brief moment in the wrong place and as a result spent the next ten years in a dungeon. Whereas Schubart's fate was the result of persecution by a local, ducal tyrant, the system introduced by Franz II/I and Metternich applied a uniformity of repression across the German micro-states. As Hoffmann found out in those seven years, no single patch could protect you for long.

Following the revolution of 1848 Hoffmann's pension was reinstated but not the professorship: the freedoms that the revolution brought were short-lived. Nevertheless, he managed to re-establish a career and he would live to see the creation of das Deutsche Reich, the 'German Empire', in 1871 by Otto von Bismarck.

Map of the newly created Deutsches Reich in 1871. Image: IEG-Maps, ibid.

Although the French under Napoleon had briefly brought certain freedoms to their conquered territories, during the restoration after 1815 France made the humiliation of the small German states one of its major foreign policy goals. The immediate provocation that led Hoffmann to write his Lied der Deutschen was the French claim to the territories of the Rhineland with their great industrial riches. This eventually led to the Franco-German war of 1870, in which the French instigators were trounced by the Germans, and accelerated the unification of the small German states into the new German Reich.

The French never forgot that humiliation, which led to the First World War, which then led to the Versailles Treaty, which was designed principally to humiliate the Germans, leading from thence to the Second World War.

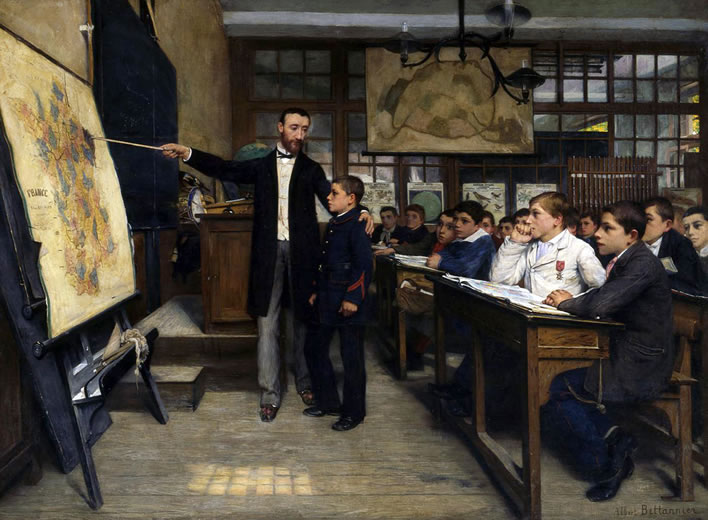

Albert Bettanier (1851-1932), La tache noire (The black stain), 1887. Image: ©DHM/Berlin, analysis (French) L'Histoire par l'image

A French teacher pointing out the 'stain' of the German occupation of Alsace-Lorraine. The occupation took place in 1872, shortly after the disastrous Franco-Prussian War. The flames of French resentment at the occupation were fanned and propagated down the generations until they finally flared up in the mutual butchery of the French and Germans at Verdun in the First World War.

Das Lied der Deutschen

Unpolitische Lieder contains a number of poems that were set to Joseph Haydn's melody. The most famous of these lyrics, however, is Das Lied der Deutschen, which he wrote on 26 August 1841 in Heligoland. Let's inspect it verse by verse.

Das Lied der Deutschen 1

Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles,2,3,4

Über Alles in der Welt,5

Wenn es stets zu Schutz und Trutze6

Brüderlich zusammenhält,7

Von der Maas bis an die Memel,

Von der Etsch bis an den Belt 8–

Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles,

Über Alles in der Welt!

The song of the Germans

Germany, Germany before anything else,

Before anything else in the world,

When for its defence

It stands fraternally united,

From the Meuse to the Memel,

From the Adige to the Belt –

Germany, Germany before anything else,

Before anything else in the world!

Notes

In this stanza Hoffmann demands a lot from his readers or singers. There is only one verb, zusammenhält, 'holds together'. All the other text consists of verbless statements that defy conventional parsing and analysis, not helped by the stream-of-consciousness-style punctuation. This is the fundamental reason why we have so much difficulty in understanding and translating this text unambiguously. The poem is not a reasoned disquisition on 'Germanness': it is a series of rhetorical devices used to evoke a mood and feelings and inspire action. This is is rhymed and metrical oratory, almost a text collage.

- Hoffmann's poem is often incorrectly titled Das Deutschlandlied, which is quite different from the title its creator gave it: Das Lied der Deutschen, The song of the Germans (see point 2).

-

Deutschland did not exist as a political entity at this time – it only came into political use after the end of the Second World War in 1945. Before that we had only the Deutsches Kaiserreich, (1871-1918), a term which was retained by its successor, the Weimarer Republik (1918-1933), and was transmuted into the (Groß)deutsches Reich (1933-1945).

In order to understand Hoffmann's poem we have to clear our minds of all these later associations and take Deutschland to mean simply das Land der Deutschen, 'the land of the Germans'. 'Germany' is the least worst short translation: 'Alemannia' or 'Germania' (which Heine occasionally used) would just cause even more confusion.

Deutschland has been used ever since the Middle Ages to denote some vaguely specified territory containing 'Germans' and would be so understood in Hoffmann's time. Centuries before Hoffmann, the Holy Roman Empire acquired the mysterious addition deutscher Nation, 'of the German Nation' – yet another twist we merely mention and move on. More topically, Heine had titled his 1844 collection of satirical poems Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen. Hoffmann's exclamation Deutschland is a call for the unification of the patches of the quilt in the face of French aggression. - Über is not used in the sense of position or implied dominance: it should not be understood or translated as 'over'. Nor should Alles be understood to mean 'others'. [The capitalisation of the original has been retained here.] The Anglo-Saxon and French revulsion at Deutschland über Alles is unjustified: in this case Hofmann would have written Alle. This point is also made by the philologist Victor Klemperer, who, as a Jewish survivor of both the Nazis and the air raids on Dresden, had no motive to rescue the anthem. In his analysis of the use of language by the National Socialists, LTI [p. 334], he notes that the phrase should not be taken to express some desire for domination, but is rather the 'esteem for the spirit that the patriot has for his Fatherland'.

- Hoffmann's repetition of Deutschland in the first line is masterful. It is what makes this piece so memorable. It makes an anthem out of a poem, to be shouted at the barricades.

- The phrase is meant to set a general political priority that should take precedence over local political considerations by the princelings of the time. Note, once again, Hoffmann did not write Alle.

- Schutz and Trutze was a common phrase at the time. Both words mean about the same thing: 'defence' or 'protection'.

- Brüderlich, 'brotherly', 'fraternally' inevitably recalls Schiller's 'Oath on the Rütli' in Wilhelm Tell (1805?) [2:2:1447-53]: 'We want to be a single nation of brothers'. Brüderlich is used again in verse 3. Given Hoffmann's detestation of the French, he is unlikely to be alluding to the Fraternité of the French Revolution.

- We should not expect too much precision from the boundaries Hoffmann sets to his Deutschland– they just reinforce its generic nature. The poet is here doing nothing more than contrasting the vast sweep of territory containing about 30 million people that is in some way 'German' with the little patches of the current quilt.

Von der Maas bis an die Memel, | Von der Etsch bis an den Belt. Image: Wikipedia.

Deutsche Frauen, deutsche Treue,1

Deutscher Wein und deutscher Sang2

Sollen in der Welt behalten

Ihren alten schönen Klang,3

Uns zu edler That begeistern

Unser ganzes Leben lang –

Deutsche Frauen, deutsche Treue,

Deutscher Wein und deutscher Sang!

German women, German loyalty,

German wine and German song

Shall retain in the world

Their old beautiful sound,

And inspire us to noble deeds

Throughout all our lives –

German women, German loyalty,

German wine and German song!

Notes

- German loyalty or fidelity is to be contrasted here particularly with the devious practices of the French, a people intensely disliked by Hoffmann.

- 'German wine', another implicit contrast with the French. We note in passing that the Austrian Empire was fond of Hungarian wine, which made a pleasant contrast to the acidic rubbish drunk at Heurigen. Austrian doctors warned of the evil consequences of the regular consumption of this vinegar substitute. Since the Viennese were also addicted to eating mountains of meat the acidic wine may have been a welcome palate cleanser.

Memories, too, of Wer nicht liebt Wein, Weib und Gesang, der bleibt ein Narr sein Leben lang, 'Who does not love wine, women and song will stay a fool his whole life long', thought to be written by Johann Heinrich Voß (1751-1826), who mischievously ascribed it to the person least likely to say it: sagt Doktor Martin Luther. We repeat: nothing is as it seems. The learnèd Voß, coming from extremely humble beginnings, was bitterly anti-aristocrat and fits well into the present company. - The German nationalism of the 19th-century was infused with medieval legends, tales that go back to the days before the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, when 'Germany' was still intact, as it were. They could jump over the humiliations of the treaty to remember a 'Germany' that had people such as Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) or Johannes Gutenberg (1400-1468). They could think even further back to the legend of the sleeping Barbarossa or the myths of the Loreley. Germanists such as Hoffman himself and Anton von Spaun (1790-1849), whom we know as a friend of Schubert's, recovered the early texts, the brothers Grimm (Jacob 1785–1863 and Wilhelm 1786–1859) collected tales and sagas, Achim von Arnim (1781-1831) and Clemens Brentano (1778-1842) collected (usually invented) a 'poetry of the common people' in the extremely influential anthology Des Knaben Wunderhorn (1805/8), Moritz von Schwind (1804-1871), another Schubert friend, painted scenes of past legends. Many of the obsessives went back to Hermann's (not his name) victory over the Roman legions under Varus in the Teutoburg Forest (location unknown) (sometime) in the 9th-century AD. Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) wrote an amusing satire on this 'Hermann' nonsense in Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen, 'Caput XI', published in 1844, not long after Hoffmann had written his anthem.

The National Socialists took the mythmaking to a new level of stupidity, which went well beyond the bounds of the historical culture, but that's another story. It did not end well.

Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit1

Für das deutsche Vaterland!2

Danach laßt uns alle streben

Brüderlich mit Herz und Hand!

Einigkeit und Recht und Freiheit

Sind des Glückes Unterpfand –

Blüh' im Glanze dieses Glückes,

Blühe, deutsches Vaterland!

Unity and justice and freedom

For the German Fatherland!

Towards that let us all strive

With heart and hand as brothers!

Unity and justice and freedom

Are the guarantees of happiness –

Flourish in the radiance of this happiness,

Flourish, German fatherland!

Notes

- Einigkeit, 'unity', 'agreement', is listed as the first of the three virtues, reinforcing the priority of über Alles, 'before anything else'. Readers of Wilhelm Tell will remember the multiple calls for the maintenance of unity over local interest between the three first cantons. Recht should probably be understood as 'constitutional law'.

- Of course, after the experiences of the Second World War, 'Fatherland' now grates on English and American ears, especially in our new era of racial and cultural 'diversity'. We make an exception for the Welsh, who sing their anthem, 'Land of my Fathers', quite unthreateningly.

Well, it was for this and other pieces of outrageous rabble-rousing which demanded unity, justice and freedom that Hoffmann was sacked, expelled and chased from place to place around Germany for seven years.

Germany arises…

Haydn's music and some suitable lyrics remained the anthem of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until its collapse in 1918. Much rewriting was done, but the constant factor was always Haydn's music.

In Bismarck's new Deutsches Reich, in which, from the hothead's point of view, multiple feudal autocrats had merely been replaced by a single feudal autocrat, the implicit republicanism of Hoffmann's text was unwelcome.

From that point every subsequent age took what they wanted from Hoffmann's poem. The third verse was anathema to the despots of the early Deutsches Reich. From 1891 the first verse was joy to the ears of the Alldeutscher Verband, the 'Pan-German League' who chose to read it as a plea for German expansionism: über Alles was now taken to mean über Alle, encouraged by Hoffmann's verb-free ambiguities.

Heinrich Heine, one of the most intelligent heads of the 19th-century, had sensed quite clearly where the 'Goethe-cult' would lead: the Germans and their culture were now better than anyone else and the sooner the Germans took control of Europe, the better. Even nowadays, the joking remark to those foreigners struggling with the German language, deutsche Sprache, schwere Sprache!, may be harmlessly intended as a consolation, but is, in fact, a deep-seated belief that, of the nations of the world, only the particularly intelligent Germans are capable of mastering this linguistic dinosaur.

The German people managed without an official anthem until 1922, when all Haydn's music and all three of Hoffmann's verses were adopted as the official national anthem of the Weimar Republic, a.k.a. Deutsches Reich. When the National Socialists took power in 1939 Hoffmann's text did not pass the Nazi sniff-test: firstly, it had been the official anthem of the detested Weimar Republic; secondly, all that unity, justice and freedom stuff was as out of place under the new autocrats as it had been under all the earlier autocrats. Still, it was a nice tune and the first verse is usable, so only that was sung. The National Socialists much preferred songs you could march to and so the Horst-Wessel-Lied, Nazi through and through, became the song to sing. Haydn and Hoffmann were still there, but only just.

Arising from the rubble in 1949 the 'Land of the Germans' finally got the word Deutchland in its name: Bundesrepublik Deutschland. It was once again a partial state, its eastern territories split off.

In fact, that is not true – remember: 'nothing is as it seems' – because it wasn't even a state. The Allied powers, following the French, the nation who had actually suffered least from the Second World War, made its statehood conditional upon its integration with the French-led European 'project' that would eventually become the European Union. The French would design the project and the Germans would be allowed to pay for it. The Bundesrepublik Deutschland actually only became a real, independent state in 1990, on its way to the reunification of its two parts.

Nevertheless, Haydn's tune still survived – just too good not to be used – and even Hoffmann's text was still cherry-picked. Although Hoffmann's first two verses could have been interpreted as a call for the reunification that would take another half-century to achieve, they were still associated too closely with the Pan-German League's interpretation. The first verse was dropped. The second had to go, too, since it is tricky to start a national anthem with an appeal to women, wine and song. The third verse remained, with all its right-on talk of unity, justice and freedom, and eventually became the anthem of this new Deutschland in 1952.

…and falls

Of course, since Hoffman's third verse has become officially German, it enjoys legal protection from parody and mockery, an irony that surely would have made Hoffmann laugh. But in all this upright Germanness we need a troublemaker and malcontent, quite in the style of Hoffmann, to cheer us up a bit.

Bernward Vesper (1938-1971) was a writer and publisher, lover of Gudrun Ensslin (1940-1977), the Red Army Faction (RAF) terrorist with whom he fathered a child. She left him for another terrorist, a bit of rough called Andreas Baader (1943-1977). Ensslin and Baader killed themselves in the infamous group suicide in Stammheim Prison, near Stuttgart.

Vesper undertook some publishing ventures under the banner of 'Voltaire', which tells us clearly what he was at. His drug experimentation appears to have driven him mad. He took his own life with an overdose of sleeping pills in a psychiatric clinic in 1971.

He left a strange autobiographical book behind – I lost patience with it eventually – called Die Reise, 'The Journey', that was first published in 1977, six years after his death and in the year that Ensslin and Baader committed suicide. I told you this would cheer you up.

Among Vesper's childhood recollections of post-war Germany just after Die Stunde Null we learn of one further text variation to Haydn's tune:

Deutschland, Deutschland ohne alles

ohne Butter, Fleisch und Speck

und das bißchen Marmelade

frißt uns die Besatzung weg

Vesper, Bernward, Die Reise, Jossa:März, 1977, p. 505.

Germany, Germany without anything,

without butter, meat and bacon

and the bit of jam we have

is gobbled up by the occupiers.

Heinrich Heine would certainly have approved. Hoffmann von Fallersleben, too, I suspect. Haydn, probably not.

Haydn's music lives on intact; Haschka's text is deservedly forgotten; Hoffmann's text has been battered and diced during the passage of 170 tumultuous years and is now beyond restoration. The east is light: time to let these shades go back to the darkness of history.

Update 14.02.2017

Last Saturday, 11 February, at a tennis match in Hawaii between Germany and the USA, the US Tennis Association put up the local singer Will Kimball (?) to belt out the German National Anthem. Mr Kimball's performance transformed him from obscure Hawaiian yodeller to internet sensation in one minute thirty seconds. So it goes these days – it took Caruso decades to achieve comparable fame. And he could sing.

As you have no doubt read elsewhere, Mr Kimball sang the first verse of Fallersleben's text to Haydn's music. This turned out to be a stellar career move. Snowflakes around the world trembled and melted at the affront. After losing her match, the German player Andrea Petkovic – actually a Bosnian Serb – gave media interviews expressing her hurt: she had been close to tears at Mr Kimball's performance. We, too, Andrea, we, too.

The most interesting thing for us about the reaction was not the frantic virtue-signalling by the snowflakes – that was only to be expected – but the surprising ignorance about poor old Fallersleben's lyrics: can there be people in the world who do not read this blog?

For the Daily Caller it was a 'Nazi-Era Anthem'. The Blaze tells us the 'Nazi-era version' was 'used as Nazi propaganda during Adolf Hitler reign' and that 'the piece was originally written in 1841 by the Austrian composer Franz Joseph Haydn, decades before Hitler rose to power'.

Even some Germans flipped out. A caption writer on Die Welt in a rush of blood to the brain called it the 'Nazi battle-hymn', before calmer counsels prevailed and this phrase was edited out, we are told.Die Welt's account of the history of the anthem, however, was more or less fair. After all, Germans should really know this stuff.

From the point of view of this blog, the worst aspect of all this was Mr Kimball's singing: consonant-free hooting. Oh, and his dress sense – you can get away with a lot of things if you are smartly dressed and wearing a sober tie. Look at the SS: all very natty in Hugo Boss.

Here is the video of Mr Kimball's performance, amusingly titled 'Fed Cup fail - Nazi anthem Deutschland uber alles'. Don't watch this video if you are a music lover. But if you do, keep an eye on the German girls.

The German journalist Jürgen Elsässer was amused by the reaction of the German team members:

If you look at the video carefully you will see that our girls were not all that distressed. Some were really having fun and wearing wicked grins… There is indeed still hope that the second verse of the anthem 'German women, German loyalty' is still valid.

[Wenn man das Video aber genau ankuckt, dann sieht man, dass unsere Mädels nicht alle so sturzbetroffen waren. Einige hatten richtig Spaß und ein schelmisches Feixen… Es besteht doch noch Hoffnung, dass auch die zweite Strophe der Hymne („Deutsche Frauen, deutsche Treue“) ihre Gültigkeit behält.]

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!