1779. Charlotte: the second Gotthard journey

Richard Law, UTC 2017-09-20 10:18

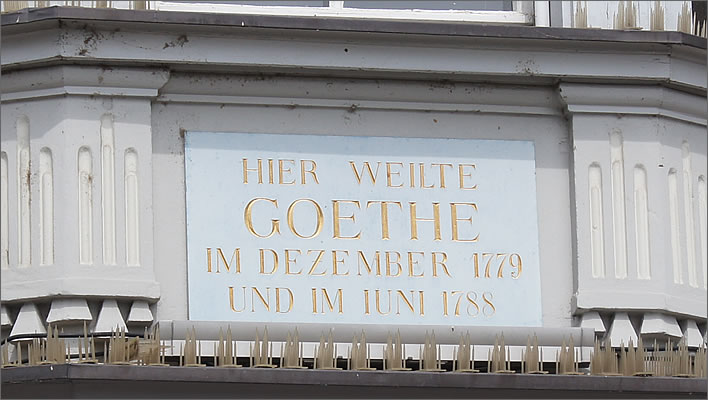

Four years after his first encounter with the Gotthard Pass, Goethe, now 30, had shed the tedious lawering in Frankfurt and Wetzlar. He was now a government official at the court of Duke Carl August of Weimar (1757-1828). Goethe's association with Weimar would last for the rest of his long life and would be the solid foundation that supported all his subsequent writings and dabblings.

Although this blog's timing of anniversaries is generally lax, this time we are spot on: Duke Carl August was born 260 years ago on 3 September 2017.

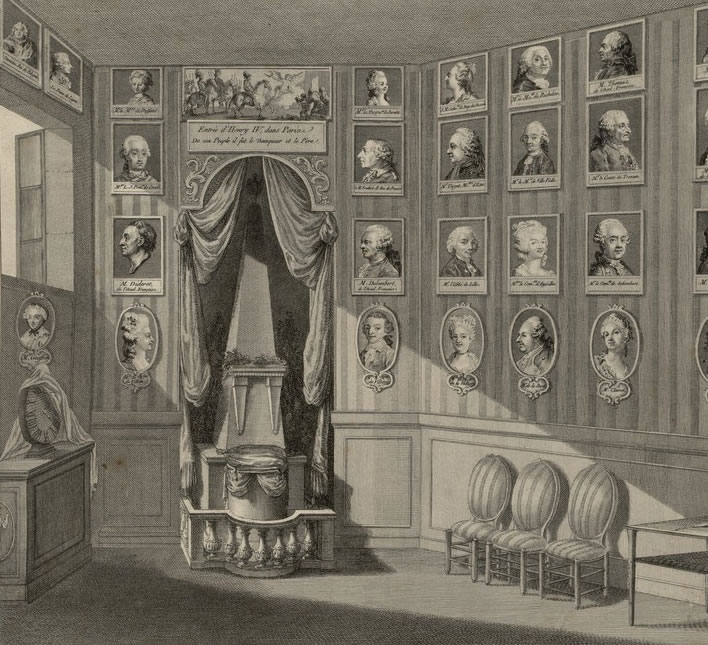

Carl August von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1757-1828) in a portrait painted around 1796 by Georg Melchior Kraus (1737-1806) based on a preliminary picture by Johann Friedrich August Tischbein (1750-1812). This picture was described in the previous chapter.

It is often asserted that Goethe became friends with his Duke and that the Duke's admiration for Goethe allowed him to make a career at the court in Weimar. This is true, but for the modern reader misleading – friendship in a feudal court had its limits. For the eight years until he was ennobled in 1782, Goethe remained as far as court protocol was concerned a commoner. He could only be received by the Duke in the Duke's private rooms; he could not dine at the Duke's table, but had to take the lowest position at the so-called 'Marshall's table', a separate table set up for the lower nobility and under-age aristocrats.

Goethe was appointed as a Geheimrat, a 'Privy Councillor' on 6 September 1779, a few days before the journey to Switzerland began: a notable step up on the ladder for the commoner, but it would take him another three years to get off the commoners' ladder and start climbing the aristocrats' ladder.

At the time of Goethe's arrival in Weimar, the Duke was eighteen and Goethe twenty-six. Carl August's father had died less than a year after his son's birth and the youngster was raised under the regency of his mother until he turned eighteen in 1775.

Bringing Goethe to his court was therefore one of Carl August's first independent acts. The eight year age difference has to be borne in mind when we write about their relationship. As Goethe himself pointed out in respect of his relationship in Strasbourg with Herder, who was five year older than he, an age difference of a few years is a big difference when you are young. [Dichtung (2:10)433]

We also often read that their journey to Switzerland in 1779 was undertaken as a Bildungsreise, an 'educational journey'. Well, that's one way of looking at it, but it started off as something quite different – an introduction for the Duke into the world of Goethe.

The companions

The adventure began as a trip by the Duke to the autumnal Rhine valley. Who better to take along as your guide than Goethe, the Frankfurter?

Dukes don't go anywhere without an entourage, so in addition to Goethe, Carl August took one of his fourteen Chamberlains, Oberforstmeister Otto Joachim Moritz von Wedel (1752-1794), known as the der schöne Wedel, 'the handsome Wedel', which may – may – have connotations that we would rather not discuss on this family-friendly blog. As a boy Wedel had been a hunting page for Carl August's father and was a close friend of the Duke's. He had been appointed to his two positions in quick succession in 1776, shortly after Goethe arrived in Weimar.

The title Oberforstmeister should not be taken in a literal sense as 'Chief Forester'. There were seven of them at the time and the post was generally a high administrative position which gave courtiers an opportunity for brief bursts of occupational therapy. 'Director of a forestry department' would be more accurate.

Wedel was the handsome, charming courtier to his fingertips: well-educated, easy-going, keen on amateur dramatics in the court theatre, a cavalier in the best sense. He was popular with the ladies of the court – and the men, too – and was a particular intimate of the Duke, who 'loved him dearly'. He was good-natured and able to laugh along with the court comedians who wrote satires about him and made silly puns on his name: Fliegen-Wedel, the 'fly-swatter'. It is no surprise that this gregarious, flexible and sensitive man also became a good friend of Goethe's. He was, in short, an obvious choice as someone to accompany his Duke and the new Geheimrat to Frankfurt.

Unfortunately, when later the group decided to set off from Frankfurt on a tour of Switzerland, Wedel ostensibly had a very great disadvantage: he had no head for heights.

The three principals in the journey also needed their support staff. Goethe took his manservant Philipp Seidel (1755-1820), another Frankfurter, with him. Seidel had worked for Goethe's parents until 1775, when Goethe's mother sent him off to Weimar to be her son's manservant. He was 24 at the time of the journey. Seidel was needed not just to hang up Goethe's trousers and clean his boots but to take his dictation and make copies of his letters. He was no yokel underling – it would be more accurate to call him Goethe's amanuensis. A time would also come when Seidel was lending his boss money to tide him over the odd financial emergency.

The Duke had his manservant, Konrad Wagner, with him and one of the court grooms, Johann Friedrich Blochberg, to look after the horses. Last but not least there was a certain 'Jäger Hermann', 'Hunter Hermann' was with the group. It is assumed by some that this refers to Johann Hermann Becker, who was a hunter in Wedel's department, but I have never found any reference to him in the Weimarer Staatskalendar, an especial irritant, because he was ultimately the third man, who would stand alone with his Duke and Goethe on the Gotthard Pass summit.

The documentary record presents a further difficulty in tracking the doings of the travellers: Duke Carl August frequently liked to go under an alias, like some of the other 18th century nobles we have come across on this blog. Great fun when they wanted to get someone to drop their guard, but a nuisance for historians. In those days before photography it was an easy thing to do.

Just to make things worse, Carl August's favoured alias was 'von Wedel', either as Kammerherr 'Chamberlain' or Oberforstmeister, 'Chief Forestry Administrator' von Wedel. The real von Wedel then used the other title. Goethe's friend Johann Heinrich Merck (1741-1791) wrote from Darmstadt to Carl August's mother, the Duchess Anna Amalia – they both enjoyed a good gossip – to tell her that the voyagers were travelling under the 'strictest incognito' and that even Goethe's mother, normally so communicative, appeared to have received 'strict orders'. [Merck 2:285, 17 September 1779]

One other travelling companion was with them, if only as the woman in Goethe's head: Charlotte von Stein. There was always a woman in Goethe's head, sometimes several at a time. On his previous journey to Switzerland the women on his mind had been the young Lili Schönemann, nine years his junior, and his penfriend 'Gustgen', Augusta Louise Stolberg. Now, in Weimar, his muse was seven years his senior, the married Charlotte von Stein (1742-1827). During the entire journey Goethe was scribbling to Charlotte.

This image of Charlotte von Stein (1742-1827) is from a postcard series of 'Goethe's female friends'. It and all the images like it derive from an undated self-portrait of Charlotte's that she made using two mirrors. We are told that no other portrait was ever made. Charlotte had a 12-year relationship with Goethe (1775-1788). She would be unceremoniously dumped like all his other girlfriends. Image: Goethezeitportal.

Goethe's taste for other men's wives and sweethearts was one of his surest character traits. Unattached women – Friederike, Lili – seem to have been a commitment-threat he would always ultimately flee. In contrast, attached women – Caroline Flachsland (Herder's 'half-fiancée'), Charlotte Buff and now Charlotte von Stein – were easy zipless flirts, each one a confirmation of the superiority of his Mephistophelian genius over the plodders whom they had married. They were easy to charm and equally easy to dump. As we shall see, even Lili Schönemann, once safely married, got the Goethe-flirt treatment.

A fine portrait of Johann Gottfried Herder by Anton Graff (1736-1813), c. 1775. Image: Gleimhaus Halberstadt, Porträtsammlung Freundschaftstempel. Online.

Marie Carolina Herder, née Flachsland (1750-1809) got to know Herder in Darmstadt in 1770. They married in 1773. The portrait shown here is a copy made in 1941 of an aquarelle entitled 'Caroline Herder as Psyche' done sometime after 1773. The original is/was in the Kirms-Krakow-Haus in Weimar: give them 3 EUR and they might just let you see it. Image: Gleimhaus Halberstadt, Porträtsammlung Freundschaftstempel. Online.

The golden autumn

The party left Schloß Ettersburg in Weimar on Sunday 12 September 1779. It had been a wonderful summer that year – if anything, autumn was proving to be even more wonderful. In such years the Rhine valley was a wonderful place to be. A golden land of trees laden with fruit, their branches propped to support the weight, nut-trees, vegetables, cereals and vines heavy with grapes. The Rhine mitigates the cold and tempers the heat. The sun catches the sides of the rift valley through which the river flows and chill air drains away. The 'Little Ice Age' was certainly a factor in that century, but in the autumn of 1779 there was no trace of it. In one of his chatty letters to Duchess Anna Amalia, Merck, a keen gardner, noted the exceptional conditions in the region:

My potatoes have flourished and the grapes are improving all the time. During a recent visit in Nierstein I came across a four year old vine bearing 184 bunches of grapes. Around here we are thinking that we haven't had such a wine harvest in the last 20 years. All our fruit trees are breaking [under the weight] and people talk of nothing but making cider, just to use up the fruit somehow.

Merck 2:269 Johann Heinrich Merck to Anna Amalia von Sachsen-Weimar und Eisenach. Darmstadt, 16 August 1779.

The ducal journey into this Garden of Eden may even have been conceived at Merck's prompting. After a number of stops that don't concern us the group arrived in Frankfurt on Saturday 18 September.

At home with the Goethes

The travellers stayed in the Goethe family house in the Hirschgraben in Frankfurt. Goethe had already warned his mother in mid-August of the visit. A bed – a clean sack of straw covered with a fine linen bedsheet and a light blanket – was prepared for the Duke in the smaller room next to the living room. Wedel was given a room at the back of the house, the servants had a small room on the first floor, the Kaminstübgen, through which the chimney of the kitchen stove ran. Goethe stayed in the room of his youth on the third floor. There was be no fuss: meals should be simple middle-class fare. All the accounts of the Duke's stay with the Goethe family give an impression of great domestic warmth and normality.

Goethe's parents knew approximately when the group would be arriving, but the travellers dismounted well before the house and crept up to it, rang the bell and entered straight away. Goethe's mother, sitting at the table in the 'Blue Room', was almost speechless with joy. The Duke and Wedel, the two cavaliers, coped with the potentially embarrassing emotion of the situation gracefully. Goethe had already told his parents that they would find courtier Wedel to be a fine guest. Wedel could get on with anyone.

Goethe's parents hadn't seen their son for four years. Their joy at his return, particularly in this illustrious company, was enormous, but may have been the trigger for the first of his father's strokes that autumn. The second would follow a year later and would leave him completely paralysed. He would die in May 1782.

The Swiss adventure is conceived

Goethe's old friend Merck joined the group from nearby Darmstadt. Merck claimed to be the initiator of the idea to go to Switzerland, although Goethe may have had the project in the back of his head from the start. Merck himself told Wieland in a letter that the project of a Swiss tour was conceived in Frankfurt:

They are certainly not going to Italy, if they are, then they lied convincingly. The journey to Switzerland was first conceived in Frankfurt, so it had been an easy secret to keep up until then because they didn't know it themselves.

Merck, p. 300. To Christoph Martin Wieland, Darmstadt, c. 7 October 1779.

The timeline is convincing: the group arrived in Frankfurt on 18 September. Carl August wrote to his mother from there on 21 September, in the way that all children write to their parents with news of a fait accompli:

What will you say, dearest Mother, when you read that instead of going to Düsseldorf in the morning, we are riding off to Switzerland this afternoon.

CarlAugust-1 p. 25.

A further hint, if we really need one, that the decision to extend the tour into Switzerland was taken spontaneously in Frankfurt is the fact that the group left Weimar with only modest sums of money in their pockets – around 20 or 30 Reichstaler each. The Swiss tour was an expensive jaunt that cost altogether almost 9,000 Reichstaler, for which they were at the mercy of a number of banking houses on the route: in Frankfurt, Bern, Geneva, Zurich und Schaffhausen, all of whose services cost them around 360 Reichstaler in interest and provision. They would withdraw between 100 and 200 Reichstaler at a time, showing us how pitifully small the initial carrying-cash of 30 Reichstaler had been for this Swiss grand tour. [Andreas-5 85]

How much would a Reichstaler be worth today? That is a difficult question that has no quick answer in currency units. As a rough guide, however, when Carl August tried to recruit Dr Johannes Hotze as his personal physician he offered him an annual salary of 2,000 Reichstaler. [Stettbacher 148] The total amount spent on the three months or so of the Swiss tour would have employed Dr Hotze for four and a half years.

Exorcising the past: Friederike

The group left Frankfurt on 22 September towards Darmstadt. Merck accompanied them part of the way. On 25 September, at Selz, ten kilometres north of Strasbourg, Goethe detached himself from the party to take the short detour alone to see his first love, Friederike Brion, in Sesenheim. We described this meeting here.

Goethe had had a 'sort-of' engagement to Friederike, much as he would have later with Lili Schönemann. He had broken it off abruptly and cruelly. To his astonishment he was warmly received by Friederike and her family – at least, so he told Charlotte von Stein [Briefe 25 September 1779]– and was able to continue on his journey with his conscience salved. They would never see each other again, nor – as far as we know – would they write to each other. Nowadays we call it 'closure'.

Goethe rejoined his companions in Drusenheim on the morning of the following day, 26 September, and the group entered Strasbourg together around midday, where the party stayed at the renowned hotel favoured by travelling aristocracy, Zum Rabe.

Exorcising the past: Lili

Another act of closure came in Strasbourg, when Goethe visited Lili Schönemann, whose presence he had carried in his heart on his first Gotthard adventure in 1775, when they were still sort-of engaged. That engagement had been broken off by their families shortly after his return. In August 1778 Lili became engaged to the son of an eminent banker in Strasbourg, Bernhard Friedrich von Türckheim. They were married on 25 August (no point hanging around) and their first child, Elisabeth Magdalena – another Lili – was born almost exactly a year later. Four brothers would follow her.

In the same letter in which Goethe told Charlotte about his meeting and reconciliation with Friederike he told her about his visit to Lili, which also became a moment of reconciliation:

On Sunday I met up with the rest of the group. We reached Strasbourg around midday. I went to visit Lili and found the little seven-week-old mite playing with a doll with her mother. There too I was greeted with wonderment and joy. I asked about everything and inspected every corner. Then I found to my delight that the good creature is really happily married. Her husband, from all that I have heard, seems to be upright, rational and busy, he is rich, with a fine house, a respectable family and substantial social standing etc. – everything she needs etc. – He was not around when I was there. I stayed for lunch. After lunch I went with the Duke to the cathedral. In the evening we watched 'L'Infante de Zamora' with excellent music by Paesiello. Then I went back in the moonlight to see Lili. I cannot describe the beautiful sentiments that went with me.

Briefe, Charlotte von Stein, 26 September 1779. '[E]verything she needs etc.' is, of course, Goethe-speak for 'those trivial things I could not give her, the strumpet'.

Those days, 26 and 27 September stood under the sign of the full moon, more accurately the 'harvest moon' around the autumnal equinox, the perfect accompaniment to the perfect golden autumn of that year. Goethe and Friederike, Goethe and Lili relived the old days in its light. The moon was so remarkable that Carl August, too, on the bridge at Drusenheim, experienced an unforgettable moonrise.

Exorcising the past: Cornelia

One last painful exorcism was required. On 27 September the group left Strasbourg in the morning, arriving at Emmendingen, nearly 80 km further south, that evening. Goethe went to visit the grave of his sister Cornelia, who had died in grim circumstances, 26 years old, two years before. The two had been very close – some prurient modern academics suggest unusually close.

At the family home he met Johann Georg Schlosser (1739-1799), the widower, and his new wife Johanna Fahlmer (1744–1821), describing her bitterly to Charlotte as 'the one who has taken her place, Fahlmer'. [Briefe 26 September 1779] The 18th century marriage bed rarely remained cold for long, in this case just over a year. That said, Schlosser had had to put up with a lot during his marriage to Cornelia.

There was more darkness here, if not as intimately tragic. When Goethe had last visited his sister, on that first Swiss journey, he had been accompanied by Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz (1751-1792), a person always desperate to associate himself with the master. Lenz became a literary hanger-on of Goethe's, nowadays we might even call him a stalker: he had courted the dumped Friederike for a time and even gone to live in Emmendingen.

The psychological condition of the hanger-on had always been precarious, but shortly before Goethe's second visit, Lenz's condition had developed into full-blown schizophrenia. His younger brother Karl had collected him just that June from nearby Basel and walked with him from there to the family home in Riga, an exertion that did nothing to improve the patient's condition. In Riga, his father refused to accept or support him and he was thrown onto his own devices.

It was during Goethe's visit to Emmendingen that he learned of Lenz's current state. It couldn't have been much of a surprise, since Goethe had been instrumental in getting him thrown out of Weimar three years before – his foolish pranks and insults threatened to damage Goethe's standing by association. The feudal courts of Europe were pitiless places for the sensitive soul: even at the time that Goethe was in Emmendingen malicious rumours were circulating about Lenz being made a professor of something or other. Anna Amalia remarked to Merck that 'the university that did this must be crazy'. [Merck 2:317 4 November 1779]

Lenz's decline would continue and he ended up being found dead in a Moscow street in 1792.

To Switzerland

Reconciled with Friederike and her family, reconciled with Lili and her new life, the book on sister Cornelia's distressing later years now closed and even stalker Lenz marched off to the distant east, Goethe could set off with his Duke towards Basel and the Alps with a song in his heart. The 30 year-old could put to rest some of the leftovers from the tumult of his Sturm und Drang years.

From Strasbourg the party went to Basel, then on 3 October rode on horseback through the Jura. On 5 October they visited Jean-Jacques Rousseau's (1712-1778) retreat on St. Peter's Island in the Lake of Biel/Bienne, where in this wonderful weather the wine harvest was also in full swing, just as it had been on the Rhine. In Anet they had 'eaten enough grapes to last them three years', Goethe told Merck. [Merck 17-21 October 1779. p.304]

From 8 October until 19 October they did the sights of the Bernese Alps: a tour through the Bernese glacier landscape, Lauterbrunnen, cascading waterfalls, the Reichenbachfall before Sherlock Holmes fought Moriarty there, snow-capped mountains.

The south-western, French-speaking region of Switzerland was next, from 20 October until 7 November.

On 26 October, a few kilometres before Geneva, they climbed La Dôle (1,677 m/5,502 ft), a generally benign route, but the short stretch around the summit is not for the faint-hearted. Wedel very wisely stayed on level ground and went on with the horses and servants to Sergues. The view from the summit left Goethe speechless – well, not literally of course: he was able to tell us that he was speechless. After that, reunited on level ground, the whole group went on to Geneva.

Geneva

Our theme is Goethe and the Gotthard, not Goethe and Geneva, so the details of the time he and Carl August spent there from 27 October to 3 November are outside our scope. We note only that they both met some of the most remarkable people of the time there. The Duke was at first particularly impressed by the entomologist, naturalist and philosopher Charles Bonnet, whom we mentioned in the context of Goethe's first trip to Switzerland with the Stolbergs. Goethe and the Duke rode out to his country house in Genthod on 29 October. Goethe was not a fan of Bonnet's religious obsessions and it was probably under his influence that the Duke would revise his own opinion a short while later, writing to his friend Knebel with advice for a Swiss tour:

…all this together makes him [Bonnet] interesting for the stranger, but in the long run, I seriously believe, he will not do you any good; certainly not as much good at least as the Vierwaldstättersee will have done you.

CarlAugust-2 p. 22.

They also made two visits to Voltaire's (1694-1778) château at Ferney. Both Voltaire and Rousseau had died in Paris in the previous year. They were able to inspect the bedroom memorial erected to contain Voltaire's heart by the then owner of the property, Charles, marquis de Villette, a cenotaph which the Carl August rightly noted could be confused with a traditional Swiss heating stove.

Above: A detail of a contemporary etching made by François Denis Née (1732-1817) a few years after Voltaire's (1694-1778) death showing the bedroom at the Château de Voltaire at Ferney with the tomb to contain his heart. The tomb was erected by Charles, marquis de Villette (1736-1793) and Voltaire's heart was transported from Paris, where he died, to Ferney. In 1864 Voltaire's remains were declared to be the property of the French state. The Villette family gave the heart to the state. It is now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, in the base of Houdon's fine statue of the seated Voltaire. Online.

Left: A photograph of the monument in the Château de Voltaire at Ferney. As noted above, Voltaire's heart hasn't been there since 1864 so the inscription Son esprit est partout et son cœur est ici, 'His spirit is everywhere and his heart is here' is incorrect, at least in its second part. Image: Le Jour ni l'Heure.

They also made the acquaintance of the renowned (to this day) alpine researcher Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1740-1799), an acquaintance that would have consequences for their journey, as we shall soon see.

The group split up on leaving Geneva on 3 November. The equestrian group – Wedel, the two manservants Seidel and Wagner, Blochberg the groom and the horses (names unknown, sorry) – travelled through the unchallenging lowland Pays de Vaud to Wallis; the alpine party – Carl August, Goethe and, we assume, Hunter Hermann – went to Chamonix, from which base they made excursions into the glaciers of the Savoy Alps.

As it turned out, Wedel's role in leading from point to point the equestrian support party, which carried the group's essentials, was a great advantage on the tour. In fact, we may be overstating the role that his fear of heights played in his assignment to this task: he may have been foreseen for this job all along, a job that would have been oversized for two manservants and a groom.

All Switzerland's icy mountains, its glaciers, its lakes and waterfalls were breathtaking experiences for the two gentlemen and the hunter from the rolling lowlands of northern Germany. Their reports of their exploits were read with excitement at home, as Anna Amalia wrote to Merck:

The reports that I get from the travellers often make my head spin. It hurts to hear of these wonderful things yet only to be able to get near through a dim telescope. Yet I'm really pleased for them. I just do what Frau Aja [Goethe's mother] does: I shake myself a couple of times, sit down at the piano or draw, after which my ideas become rose-tinted once more.

Merck, from Anna Amalia, Weimar, 4 November 1779, p. 317.

But for Goethe, the intellectual leader of the group, the great landscape finale, that Goethe obsession, had not yet been achieved: the Gotthard Pass. That phase now began in Bex.

Meeting up

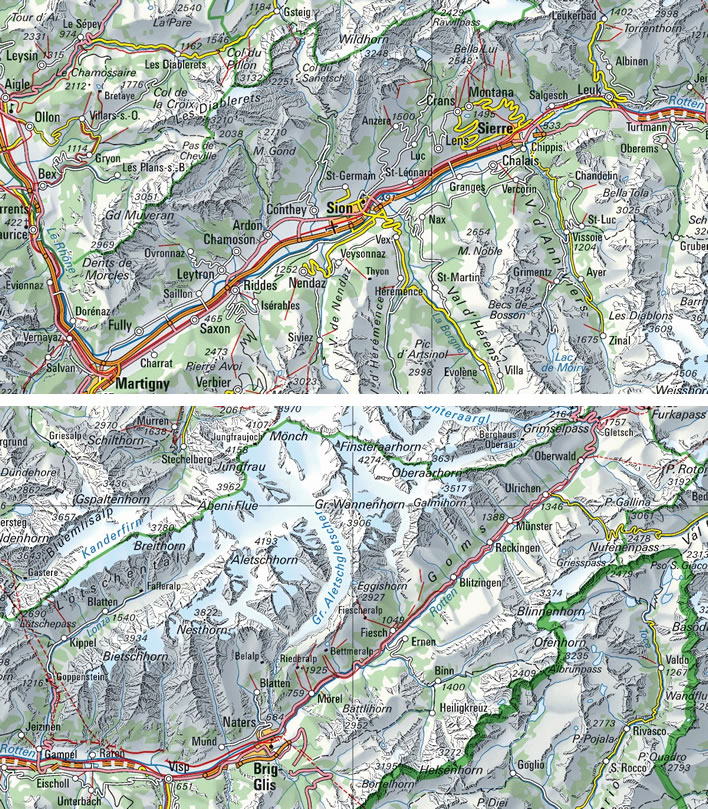

A map of the valley of the Rhône running through Wallis, in two halves. Bex and Saint-Maurice, where the groups met up, is at the far left of the top map; Münster, from where the alpinists departed at seven o'clock on the day of the crossing of the Furka Pass and Oberwald, where they recruited their two guides, are at the top right of the bottom map. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new tab of your browser, 2338 x 1079 px, 1.3MB.]. Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz (IVS).

The alpine party landed up in Martinach/Martigny (Canton Wallis offers both German and French names) on 6 November. Early the following morning they set off downstream – that is, away from the Furka – to Saint-Maurice, on the border between Canton Wallis and Canton Waadt and only about 25 km from the Lake of Geneva. Wedel and the equestrian group were waiting in Bex, a few kilometres downstream from Martinach.

The alpinists walked back down the stream and met up with the equestrians coming towards them and the full group, now reunited, returned to Martinach for the night.

The following day, 8 November, the full group set off to ride together to Siders/Sierre. The key bridge across the Rhône had been damaged and they had to make a time-consuming detour that finally got them to Sitten/Sion for dinner.

The worm turns

That evening Wedel made some remark that earned him a rebuke from Carl August. We don't know exactly what was said, but some other remarks of the Duke's suggest that Wedel, the longtime intimate companion of Carl August, had become jealous at the new-found intimacy between the duke and the commoner, the Johann-come-lately.

Adversity and shared experience in their alpine adventures had brought Carl August and Goethe close together; Wedel the wobbly, in charge of the horses, missed out on the shared adventure and seems to have been left feeling jealous, inferior and insecure in his old friend's affections. The Duke noted that Wedel, a sensitive man, a man of feelings, could not begin to participate in the intellectual complexity of Goethe's world. Nor, we add, with his fear of heights could he share the experience of the grandiose heights and dangers they knew. Carl August, for all his relative youth, displayed a remarkable insight into his old friend's psyche:

As soon as he is alone in his sensuous existence he is happy and easy-going. Goethe's existence and life alongside him flays him, he cannot enter and cannot leave.

From Carl August's Tagebuch, quoted in Andreas-3, p. 106, n. 30.

We might speculate that Wedel's weakness with his debilitating fear of heights would probably cause Goethe to feel a tacit contempt for him, a contempt which would feed the arrogance of Goethe's impression of his own superior genius. Goethe tells us in Dichtung und Wahrheit that he cured his own fear of heights by a repeated act of will at the apex of the spire of Strasbourg Cathedral. [Dichtung (2:9)400f.] Goethe's elevation of the power of the will over the frailties of the body was a characteristic of his entire adult life. We see it in the 22-year-old's dangling from the spire; in the 30-year-old's crossing of the Furka in 1779; we see it in the 81-year-old's response to the death of his son August in Rome on 27 October 1830: carry on regardless –Der Körper muß, der Geist will, 'the body must do what the spirit wants', he wrote to his friend Zelter on 2 December 1830.

In Wedel we meet the handsome courtier, the old friend of the Duke, who outranks Goethe on the feudal scale of things, refusing to face down his demons. It is hardly likely that anyone in the alpinist group openly criticised Wedel, but they didn't need to: Wedel himself must have been more and more aware of his outsider status as one vertical challenge followed another and he was left minding the horses and not accompanying his duke for much of the time.

Detour

The horses needed rest, so Goethe and the Duke set out for a night-time walk from Sitten/Sion to Siders/Sierre, leaving Wedel at the inn in Sion to reflect on his attitude. Perhaps this odd behaviour was a way of putting some distance between them and Wedel in order to allow the situation to cool down.

The following day, 9 November, Goethe and the Duke (Hunter Hermann did not accompany them) set off up a demanding and exposed path on the righthand side of the valley passing through the village of Inden and then on to the spa village of Leukerbad, arriving there about three o'clock in the afternoon. The paths here, particularly those around the Gemmipass, the mountain behind Leukerbad, are fine examples of the skill of the Walsers in creating tracks where tracks really should not be.

The path to Inden is cut into the steep rockface which encloses this amphitheatre on our lefthand side. It is not a dangerous path, it just looks terrifying. It descends across the front of a steep cliff and is secured from the chasm by a low plank along the outer, righthand edge. A chap who was descending with his mule grabbed his animal by the tail at dangerous points in order to give it some help on very steep sections of the rock.

Reise-1779 'Leukerbad, den 9., am Fuß des Gemmiberges'.

For readers who don't mind a little bowel-loosening now and again, here is a photograph of a pack-transport route in the Gemmiberg above Leukerbad. This is not a route Goethe and Carl August followed, they just looked at it and similar routes from distance during their stay in Leukerbad. It is a good illustration of the path-building techniques in Wallis.

Starting at the bottom left of the image the serpentine section of the route in the sun enters the rockface, then zigzags up the righthand side of the face, then left around the front (under the vegetated section) then runs diagonally upwards to meet the track at the top right. The section cut in the rock already existed in the Middle Ages, then some sections were dynamited free by Tyroleans around the 1740s.

Image from Aerni, Klaus, Benedetti, Sandro. 'Von der Teufelsbrücke zu "AlpTransit"', Archäologie Schweiz : Mitteilungsblatt von Archäologie Schweiz, vol 33, 2010. p. 64-69. Online.

After a very flea-bitten overnight stay – Goethe's bed was full of things hopping around and biting – they got back down to Leuk in the valley bottom at about ten o'clock on 9 November. There they met up again with Wedel, as arranged. The argument and the brief separation between Wedel and his duke had cleared the air. The Duke's handling of the situation had clearly been successful: Wedel was his cheerful self again.

This is where the alpine and the equestrian groups parted ways once more. Horses were impracticable for the rest of this route – the stabling on the route ahead was designed for pack animals such as mules, not large lowland horses, it was uncertain whether there would be an adequate or even any supply of oats and, of course, what was to come would be far too vertiginous for Wedel. The first snow of the journey had fallen, too. Once more in a dig at Wedel, Goethe tells us explicitly in his Tagebuch that it was Wedel's suggestion to take the horses back from this point. [Tagebuch-2 10 November 1779]

The parting of the ways

The plan was simple: Wedel and the equestrians would ride back down the valley of the Rhône to Bex, then through Vevey, Lausanne, Freiburg and Bern to Luzern. The alpinists – Goethe, Carl August and Hunter Hermann – would ascend the Furka Pass, descend the Gotthard Pass then sail across the Vierwaldstättersee to arrive in Luzern, where they would all meet up again on 16 November.

The alpinists packed their necessities into a saddlebag panier, hired a mule and driver to carry it and set off on foot towards Brig, where they arrived at about ten o'clock that evening.

Brig was an important waypoint in their journey. It wasn't exactly a point of no return, because should the Furka Pass prove too risky or too much for them they could always retrace their steps to Brig and take the long, circuitous but winter-safe route, passable by horses, over the Simplon Pass, Domodossola, the Lago Maggiore, then Bellinzona, then to ascend to the Gotthard from the Tessin side. This is the rational route that the experienced alpinist Saussure had advised them to take in the first place.

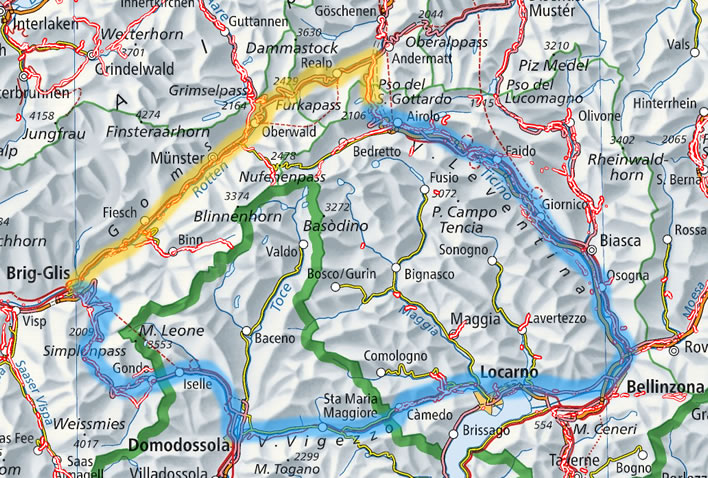

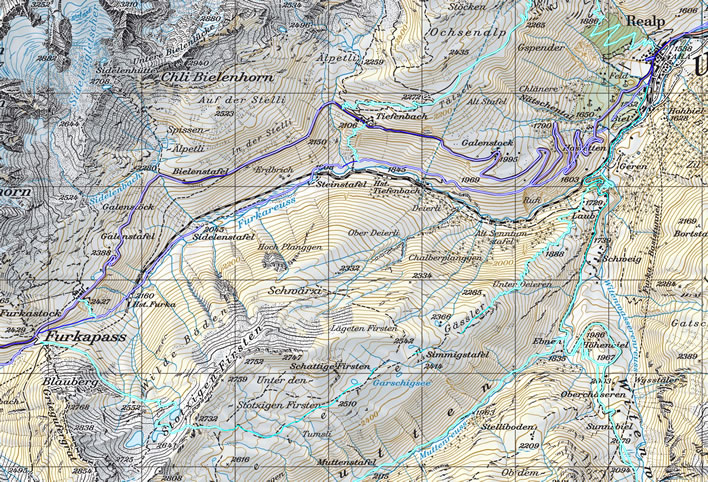

The two ways to the Gotthard Pass from the west.

The genius and the hothead took the direttissima route [shaded yellow] along the diagonal from Brig (middle left), to Münster, Oberwald then over the Furka Pass, right at Hopsental and then up to the Gotthard Pass summit (top centre), around 75 km that would take them about three days in deep snow.

The thinking person's route [shaded blue] suggested by the experienced Saussure follows the curve around the bottom of the map: Brig, over the Simplon Pass to Domodossola, then across to Locarno and Bellinzona, then follow the Ticino up to Biasca, Airolo to reach the Gotthard Pass summit from the Italian side, a distance of about 170 km that would take at least six days. (IVS).

It would, however, have taken them five or six days longer to get to Wedel in Luzern. In rejecting that route they were throwing over the advice they had so gratefully received from Saussure in Geneva when it suited them and ignoring the agreement with the 'old aunts' there. If only the old aunts knew what they were about to do.

Saussure's route over the Simplon Pass was a nice possibility, but only that: Goethe hated retracing his steps. Every year, even today, the mountains teach lessons of varying severity to those with that attitude, among them your author. With his hothead duke in tow on a route that Saussure, the man in the know, had dismissed, would they have ever turned back?

They left Brig early the following morning, 11 November. They hired a donkey, a driver and two horses for the next stretch of the route to the village of Münster, a distance of about 27 km and a maximum ascent of 1,000 m. Presumably, Hermann used the traditional conveyence of the underling, Shanks's Pony, but it has to be said that Goethe and Carl August also did a fair bit of walking along the tricky stretches – 'disgusting tracks', often precipitous – with their unfamiliar horses. The journey was extremely cold and took them into ever more ice and snow as they ascended. They arrived in Münster at six in the evening. The mood was bleak.

On the way they asked various people they met about a crossing of the Furka Pass in winter, but they all had no idea, even though they were only a couple of hours away from the pass. Normal people would take that as a hint that such a journey might be unwise, to say the least. Predictably, Goethe confesses how annoyed he would be if they had to turn back: at every step his hubris grows and the distance they would have to return grows too.

They left Münster at about seven in the morning the following day, 12 November, and took two hours to reach Oberwald, the village at the foot of the Furka Pass.

Dicing with death

Goethe, the tour guide for a Duke, was running risks with his charge, but just as when he was dangling over the abyss on the top of the spire of Strasbourg Cathedral or when he was on his first journey up and down the abyss of the Gotthard Pass, he sought a challenge for himself and one for his Duke.

In doing so he was risking the obliteration of a dynasty: Carl August had no male children at the time, his younger brother Friedrich Ferdinand would die of dysentery without a legitimate heir in 1793 and that would have been that with the House of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach. Falling in battle was one thing, falling off a cliff or being frozen to death on a foolhardy winter tour in the Alps was another.

Were I on my own I would have gone higher and deeper, but with the Duke I have to be moderate. I could allow us to do more, if only he didn't have the bad habit of wanting to gild the lily ['den Speck zu spicken' ~ to lard the fat] so that when we have reached the peak of the mountain after effort and danger, then to look for a further, pointless and unnecessary path with effort and danger.

Briefe, Charlotte von Stein, 14 October 1779.

In other words, according to Goethe, we should not think of this situation as the genius dragging his duke into testing situations, but as the older, experienced man keeping the young hothead away from unnecessary danger. Goethe had been warned about the risks he was running and the personal responsibility he bore, as he tells us:

The result will decide whether our courage and confidence that it would happen, or the cleverness of some people who counseled us with force not to go this way, will be proved right. So much is sure, that both, cleverness and courage, have to recognise that luck is paramount.

Reise-1779, Münster, 11 November 1779, 'abends 6 Uhr'.

Those 'clever people' had been in Geneva. Writing to Charlotte on 2 November, he tells her that they were the sort of 'old aunts' that were to be found everywhere who, because 'they have nothing better to do, believed they have the right to stick their noses into other people's business'. They wanted to prevent – with 'the most serious protestations' – the Duke going to the mountains of Savoy and particularly the Gotthard, even though it was his idea and he was looking forward to it (that is, the hothead himself wanted to do it).

The 'old aunts' wanted to turn it into a political affair and a matter of conscience, so that Goethe and the Duke were forced to seek the opinion of an experienced person. For that person they chose the renowned Alpine researcher Horace-Bénédict de Saussure (1740-1799), then Professor of Philosophy in Geneva, agreeing to follow his recommendation.

After hearing both sides of the argument, to Goethe's great relief and delight Saussure told them their project would be no more dangerous now than in an earlier season of the year. Saussure also gave them a lot of helpful information for their journey. Goethe was impressed: 'That's the sort of person, it seems to me, that one should ask when you want to get on through the world.'

Saussure's breezy confidence was what Goethe and his Duke wanted to hear. We note here that Saussure was anything but risk-averse with his own life – his first ascents and hair-raising journeys in pursuit of scientific knowledge make him one of the founders of alpine climbing – but the route he proposed to the travellers was, indeed, rational and low risk.

From Brig they should take the long, circuitous but winter-safe route, passable by horses, to the Gotthard over the Simplon Pass, Domodossola, the Lago Maggiore, then Bellinzona, then to ascend to the Gotthard from the Tessin side. In the context of this route, Saussure's assertion that it would be no more dangerous in winter than summer is justified.

But the group's situation had changed. After Brig they were not going to follow Saussure's winter-safe route – to Goethe and also the hotheaded Carl August his suggestion was now simply a tedious detour.

Goethe was quite clear that he was rolling a die with his Duke: 'luck is paramount'. After their tour of the ice fields of the Savoy Alps, their attention now turned to the crowning moment of their Swiss journey: the Gotthard Pass. No rational person, unless life or money was at stake, would freely do what they now did – but the hotheaded duke and the triumph-of-the-will genius would have it no other way. We find them and Hunter Hermann trudging up the Furka Pass in November 1779, destination Gotthard Pass summit.

Over the Furka

The group left Münster in Wallis at first light, six o'clock on 12 November 1779. In Oberwald, a small village on the Rhône at the foot of the Furka Pass, they stopped at an inn to recruit guides:

We arrived after nine in the morning and went into an inn. The people there were not a little surprised to see figures like us appear at that time of the year. We asked whether the route over the Furka was still open. The told us that their people take the route through most of the winter; whether we, on the other hand, would make it remained to be seen. We asked for such people as guides; a stocky, strong man turned up, his appearance inspiring confidence. We told him our wishes: if he thinks that the route is still feasible for us he should let us know, get one or two colleagues and come with us.

Reise-1779, Realp, 12 November, 'abends'.

Goethe's account does not try to disguise the risks they were going to be running – on the contrary, those risks would become one of the objects of the journey.

After some consideration he agreed and left to get himself ready and collect some comrades. We paid off our mule-driver, since we could not go further with the animals. We ate a little cheese and bread, drank a glass of red wine and were cheerful and happy by the time our guide returned with an even bigger and stronger looking man behind him, who seemed to have the bravery and strength of a horse. One of them slung the saddlebag panier across his shoulders and our convoy of five left the village and soon reached the foot of the mountain, from where the ascent began.

Ibid.

Before setting off, one of the guides gave the Duke a cap to protect him from the cold.

We climbed left up the side of the mountain and sank in deep snow. One of our guides had to go ahead and stamp down a path for us.

It was a strange sight, when you took your eyes off the path and looked at our convoy: in this most desolate part of the world, in a vast, monotonous, snow-covered mountain wasteland, where backwards or forwards for three hours distance not a single living thing could be seen, there we were, a file of men in which one walked in the footsteps of the other. In that white-covered vastness nothing could be seen but the furrow which we had made.

[...]

Ibid.

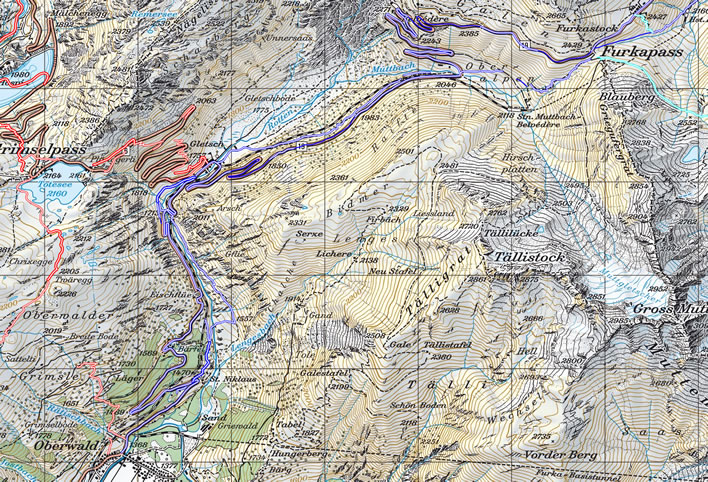

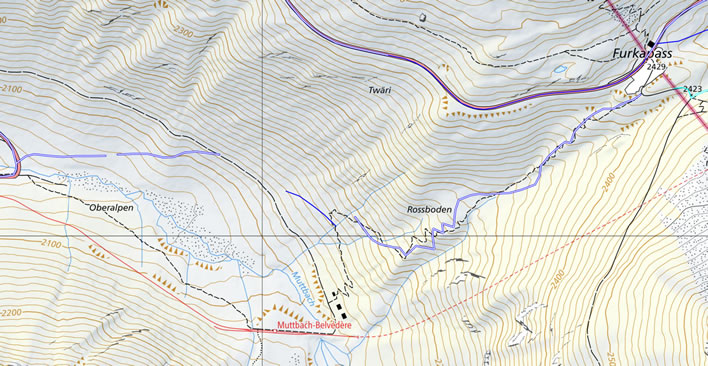

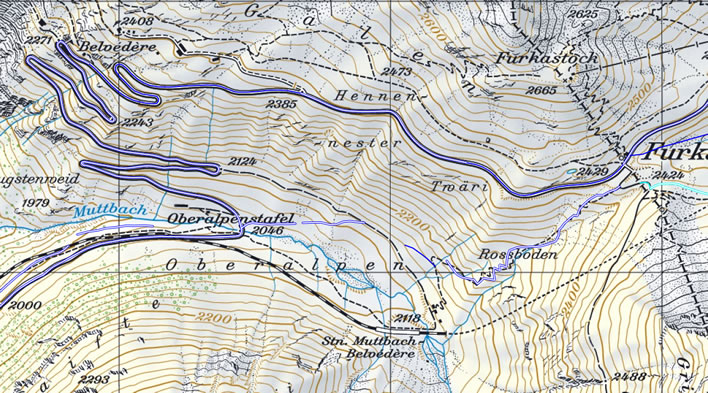

The ascent of the Furka Pass from Oberwald, bottom left, where the group hired their guides, to the pass summit, top right. The strongly dashed black line that runs across the route at the pass summit is the border between the cantons of Wallis and Uri, where Goethe mentions the wayside-cross that stood there. The old and the new routes follow very similar lines, which, in this landscape of few options, comes as no surprise. The termination of the Rhône glacier is top centre on this map, next to the serpentine section of the route.

The route from Oberwald to the pass summit is about 15 km long and involves an ascent of 1,100 m. A modern hiker would expect to take about four and a half hours for this stretch in good conditions, meaning that the group's guides got them along the route in deep snow conditions in about the same time: an exceptionally good performance. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new tab of your browser, 2338 x 1079 px, 1.3MB.]. Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz (IVS).

I am convinced that anyone without complete control of their imagination would, without any obvious objective danger, die of fear and terror. There is no danger of a fall here. Only the avalanches would be dangerous, were there more snow than at present to start rolling under its own weight.

But our guides told us that they cross here throughout the winter, carrying goatskins from Wallis up to the Gotthard, where there is a sizeable trade. In order to avoid avalanches they go a different route to our gradual ascent: they continue along the valley floor for longer and then climb the steep mountain direct. The route is safer, but more arduous.

Ibid.

The hollow blue line marks the steep alternative route the guides say was preferred by the pack carriers of the goatskin trade, considering it to be safer from avalanches. It starts from the first bend in the great serpentine, runs across the valley to enter the ascent at Rossboden, then follows the gorge up to the pass summit. The dashed black line up the same route marks the modern track that runs from the railway station Muttbach-Bélvèdere, where the line enters the railway tunnel. Going up the narrow gorge could be the safer route in respect of avalanches. However, as the guides told Goethe, an ascent of 250 m within a distance of 900 m would be arduous in deep snow. [Click on the images to open a larger version in a new tab of your browser, both approx 1303 px, 400 kB.] Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz (IVS).

The two routes in context: The gentler route the group followed is about 5.5 km from the first serpentine to the pass summit, ascending about 400 m. Taking the locals' short cut reduces the distance to about 1.7 km. As a result of the severity of that ascent, in normal conditions the short route would save only a little time. The guides knew what they were doing taking Goethe's group the long way round, even in deep snow conditions. [Click on the images to open a larger version in a new tab of your browser, both approx 1303 px, 400 kB.]. Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz (IVS).

After a four and a half hour march we arrived at the summit of the Furka Pass, at the wayside cross on the border of the cantons of Wallis and Uri. Even here we could not see the twin peaks of the Furka, the mountain that had given its name to the pass. [furka is cognate with English fork; the mountain has two peaks, the Gross and the Klein Furkahorn.]

Ibid.

We were expecting a more comfortable descent, until our guides announced that the snow was going to be even deeper, which we soon found to be true. Our convoy continued in single-file as before, but the leader, who tramped down the path, was frequently up to his waist in snow.

The skill of the guides and the cheerfulness with which they did their work kept our spirits up. I must say that for my part I was so happy that we had managed the route without great difficulty – although I should say straight away that it wasn't a stroll in the park.

Hermann the Hunter assured us that he had had snow like this in the Thuringian Forest, but then added that the Furka was however a bastard ['Schindluder']. A bearded vulture flew over us at an incredible speed; it was the only living thing that we encountered in this wasteland. In the distance we saw the peaks of the Urserental in sunshine.

Ibid.

Anyone who has walked through deep snow without snowshoes for any length of time will confirm just how strenuous that is. The altitude of the Furka Pass summit is just under 2,500 m, meaning that for unacclimatised strangers the process is extremely arduous. Hermann's bad language can be excused under the circumstances – the highest point of the Thuringian Forest is just under 1,000 m and most of it is well below that.

The stretch from the Furka Pass summit to Realp is around 10-12 km long (there are many variants) and involves a descent of about 900 m. In good conditions the modern hiker would expect to do this route in under three hours. The fact that Goethe's group, despite their sensational performance on the first stretch, took four and a half hours is an indicator of the extremely deep snow they faced and their increasing tiredness. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new tab of your browser, 1515x1031px]. Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz ( IVS).

In total the two local guides tramped down deep snow for nine hours at a single stretch. Had the guides not been there, there can be no doubt that Goethe and his party would have died of exhaustion had they been foolish enough to travel on their own.

The band of brothers

At last the group returns to some sort of civilisation – at least the presence of other human beings.

Our guides wanted to stop for something to eat in an abandoned, half snowed-in stone hut, but we forced them on, so that we did not have to stand around in the cold. At this point other valleys run together and finally we had an open view of the Ursenertal.

Ibid.

A relief map of the Furka Pass from Oberwald (bottom left), from whence the group set out at six o'clock on the morning of 12 November 1779 to Realp (top right), where the party arrived nine hours later. Goethe's description is accurate: they would only get a view of the Urserental when they finally rounded the mountain where the 'other valleys run together' (on the right of the image) just before the serpentine path takes the walkers down into Realp. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new tab of your browser, 1452x976px]. Image: Google Maps.

We speeded up and four and a half hours after we had passed the wayside cross we saw the scattered roofs of Realp. We had asked our guides a few times what kind of an inn and especially what kind of wine we could expect in Realp. They gave us no great hope, but assured us that the Capuchins there, although without a hospice like at the Gotthard, sometimes took in strangers. From them we would get a good red wine and better food than we would get at an inn.

We sent one of the guides ahead to warn the fathers of our impending arrival so that they could get everything ready and put us up. We didn't delay in following him and arrived soon after he did.

A large, handsome monk received us at the door. He bid us with great geniality to enter and asked us to bear with them, since at this time of the year they were not organized to receive guests. He led us into a warm room and busied himself helping us getting our boots off and changing our clothes. He repeatedly asked us just to behave as we would at home.

As far as the meal was concerned, he asked us to be patient, since they were still in the middle of their long fast, that went on until Christmas. We assured him that a warm room, a piece of bread and a glass of wine, in the present circumstances, were all we could wish for.

[...]

After nine. The fathers, the gentlemen, the servants and the guides all sat around one table; only the brother who was doing the cooking appeared right at the end of the meal. Out of eggs, milk and flour he had produced diverse dishes for us, which we relished, one after the other.

Ibid.

Under the stress of the circumstances the feudal order broke down and the men bonded as equals, breaking bread together in that ancient symbolism – exactly why such meal-sharing was never done at a feudal court and exactly why Goethe notes its occurrence so specifically here.

Levellers, but not for long

Goethe has taken his Duke out of his court, its separate rooms and tables, its strict protocols, where rank is the ultimate regulator of relationships between humans, and placed him in a situation where they ate the same food and drank the same wine at the same table, just as they could die together in the snow.

'We few, we happy few, we band of brothers' said Shakespeare's Henry V in a moment of peril when he needed the assistance of the riff-raff. After the job had been done and the moment of need had passed Henry forgot them again. Duke Carl August, after his moment of bonding with the low-born in a Capuchin house in Realp, would also revert to being the aristocrat. In the subsequent years back in Weimar, Goethe would become depressed and angry at his protegés reversion to type – for instance in the damage that was done to his peasants' crops by his passion for boar hunting.

Wedel the wobbly, trotting on horseback along the unchallenging roads of lowland Switzerland did not need to worry that he was not a party to this moment of male bonding, because it really changed nothing. Carl August went into Switzerland and came out again with no perceptible difference in him.

The acclamation of the genius

Goethe, the daring, exceptionalist genius, took the risk of the crossing of the Furka Pass in winter upon his own shoulders, fully in accord with the contemporary idea of the 'genius' as an intuitive risk-taker, destined to lead. Time to savour his triumph:

The guides were delighted to be able to speak of the mission we had just successfully concluded; they praised our unusual skill in walking and assured us that they would not have undertaken the task with just anybody. The confessed that, that morning, when we requested assistance, one went to look us over, whether we had the appearance that we could go with them successfully. They tried at all costs to avoid accompanying old or weak people at this time of year, because once they had accepted the task they were obliged to transport them to their destination, whether they were weak or ill or even dead, unless they were in imminent fear of their own lives.

Ibid.

We can understand his happiness in being able to report on the exceptionalism of what they had just achieved and the fact that they had all survived his die rolling.

He was not as normal men. That's how it has always been with die-rolling geniuses down the ages, whether Julius Caesar (alea iacta est), Friedrich II, Napoleon, Lenin, Hitler and so on. It all works fine – until it doesn't and Nemesis arrives in one form or another.

In Goethe's less megalomanic case his genius would do him little good as an administrator at his Duke's court: his innovations were frequently blocked and frustrated by the hundred vested interests at the feudal court.

The blessing of the full stomach

On the morning of 13 November the guides departed to return home along the path they had beaten to get here. After a hearty breakfast – Goethe notes that approvingly – the adventurers set off around ten o'clock along the Urseren valley.

Our high performance alpinists in 1779 did not know what every modern exercise fanatic knows. In that night in Realp the Duke was racked by nausea and vomiting – he had eaten 'too hastily'. It seems most likely that after nine hours of sweating effort in deep snow, in dry air at altitude, the alpinists were simply dehydrated. They had eaten nothing since early that morning: their guides, who were tramping snow and carrying loads, showed wisdom in wanting to take a break along the way, but the foolish strangers would hear nothing of it. Wine and more wine, eggs, milk and flour gobbled down then wreaked their havoc.

At this point of our tale, whilst our adventurers are trudging through the deep snow after that 'hearty breakfast', it is not at all out of place to note Goethe's passion for food and drink. Readers will already have been alerted to that passion by his pressing enquiries to the guides about the quality of the food and drink in Realp. After scoffing the bread and glugging the wine on arrival, 'which was all we could have wished for', and then a wait until a proper dinner could be confected, his relief when some real food finally arrived at nine o'clock is apparent.

Readers of his diaries, letters and travel reports will be entertained by his 'restaurant reviews' of what he put into his mouth on his journeys – that Fische gebachen geschmackt, 'delicious baked fish', in Amsteg in 1775, for example.

Our best witness of Goethe's food addiction is the witty German writer Jean Paul (1763-1825) [Johann Paul Friedrich Richter], himself an heroic drinker, who, visiting Goethe in Weimar in 1796, would note in a letter to his friend Christian Otto on 19 June: Auch frisset er entsetzlich, 'he also stuffs himself appallingly'. Paul, the master of satirical apposition, then immediately adds: Er ist mit dem feinsten Geschmack bekleidet, 'He is dressed with exquisite good taste'. A time would come when Goethe, the poetical conqueror of the Gotthard, would be barely able to get up his own stairs. What would those sylphs Friederike and Lili have said?

Jean Paul Friedrich Richter (1763-1825) painted in 1798 by Heinrich Pfenninger (1749-1815). The only portrait we have of the relatively youthful Jean Paul. Image: Gleimhaus Halberstadt, Porträtsammlung Freundschaftstempel. Online.

Jean Paul Friedrich Richter drawn in 1822 by Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein (1788-1868).

Gotthard redux

After our slight gastronomic detour we rejoin our adventurers, who by this time have reached Hospental, a key crossroads on the journey. They will go from here to the pass summit, stay overnight at the Capuchin Hospice there, then descend once more to Hospental and thence descend through the Schöllenen gorge to civilisation.

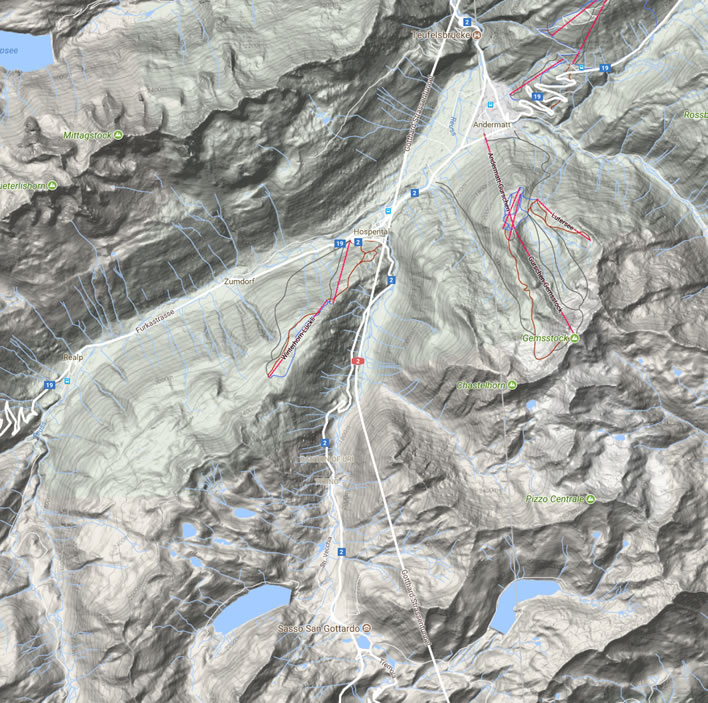

The route along the Urserental from Realp (middle-left) to Hospental (middle), about 6 km with a gentle descent of 100 m. The ancient and the modern tracks mostly follow the same line: there is nowhere else to go. Hospental is the crossing point for the east-west route along the Urserental that goes to Andermatt, the Schöllenen and the Oberalp Pass to Disentis (all top-right) and the north-south route to the Gotthard Pass summit (bottom-centre) and on to Italy. The ascent to the Gotthard Pass summit from Hospental is about 8 km long, ascends about 700 m and would take a modern walker about three hours. From Realp to the Gotthard summit would take about four hours in good conditions; the group made good time and arrived at the Gotthard Hospice at about two o'clock on 13 November and left again at nine o'clock the following morning, both according to the Duke's diary. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new tab of your browser, 1022x1141px]. Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz ( IVS).

A relief map of the Hospental crossroads. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new tab of your browser, 1065x1057px]. Image: Google Maps.

In Hospental, ever concerned about where the next meal is coming from, Goethe places an order at the inn there for lunch the following day, when they will be on their way down – there will be no waiting around for food to arrive this time.

It was here that I joined the route of my previous journey [in 1775]. We went into the inn and ordered a lunch for tomorrow, then started our ascent of the mountain.

Reise-1779, 13 November, 'Gipfel des Gotthards'.

Goethe has returned to the place that in 1775 made him feel sauwohl, 'happy as a pig'. They arrived at the pass summit around ten o'clock on 13 November 1779.

So we finally attained the summit of the mountain, which you have to imagine as a bare dome ringed around by a crown. One is here on a flat area, surrounded by peaks and the view is restricted by barren and mostly snow-covered ridges and cliffs near and far.

Ibid.

On his previous visit Goethe had also stayed overnight at the Hospice. The two Capuchin friars he met then were still on duty there. One of them, Father Seraphim, was currently in Milan, the other, Father Lorenzo was in Airolo, down the Italian side of the pass. He arrived later that day:

Father Lorenzo arrived from Airolo, so frozen, that on his arrival he could not speak. Even though up here the Capuchin monks are allowed to wear more comfortable clothes, it is still an outfit that was not designed for this climate. From Airolo he had climbed up a very icy path against the wind; his beard was frozen and it took a while before he recovered his wits.

Ibid.

Goethe's 1775 visit to the Gotthard had been in high summer. Ever since that time, he tells us, he had had a desire to see this area under snow. His wish was granted: he certainly had his fill of snow on the ascent here and in the cloudless night he got a taste of the intensity of the alpine winter:

That evening we stepped out of the door for a moment to allow the father to point out to us the highest peaks of the Gotthard. We held out barely a few minutes, so penetratingly and aggressively cold it was. After that we stayed closed up indoors until we left the following morning, having time enough to travel in our thoughts through the extraordinary things in this area.

Ibid.

Finally, towards the close of his travel account, he tells us something of why the Gotthard region holds such a special attraction for him:

You will realise, from a brief geographical description, how remarkable is this area in which we find ourselves. The Gotthard is indeed not the highest mountain in Switzerland; in Savoy, Mont Blanc is considerably higher. Yet the Gotthard can claim to be the king amongst the mountains because the great mountain chains join up here and lean upon it.

Not far from us here are two small lakes, one of which feeds the River Tessin that runs through gorges and valleys to Italy. The other in a similar manner feeds the Reuss that runs down to the Vierwaldstättersee. Not far from here is the Rhine, which flows towards the morning [east, from near the Oberalp Pass] and the Rhône, which arises at the foot of the Furka and towards the evening [west] through Wallis. We are here at a crossroads, out of which mountains and rivers flow towards all the points of the compass.

The modern version of the Gotthard watersheds, the Vier-Quellen-Weg [DE only], for walkers and bikers.

Breaking off

In 1775 Goethe had turned his back on Italy, that famous moment of the Scheideblick nach Italien. Now, in 1779, he turned his back on Italy once more, and his Duke's back, too, judging him not yet ready for that broadening of the Teutonic mind.

But the option was not really available, since Wedel, Blochberg, Seidel, Wagner and the horses would be waiting in Luzern for them. Then there was the language problem: Goethe notes diplomatically that Brother Lorenzo could only speak Italian, a language which Goethe had learned quite well as a youngster with an Italophile father, but which gave the Duke, who had just started learning Italian that spring, 'an opportunity to practise'. And finally, we recall what Merck had written about the project when they set off: 'They are certainly not going to Italy, if they are, then they lied convincingly'.

Strangely, Goethe's account, Briefe aus der Schweiz. Zweite Abteilung, 1796/1808, stops here, at the point where the door of the Gotthard Hospice closed behind the group. He doesn't even tell us what the pre-ordered lunch in Hospental was like. The party descended via the Schöllenen gorge, that combination of natural violence and human technology that had so impressed him on his first encounter with the Gotthard, through the Urnerloch, over the Teufelsbrücke past the Teufelsstein and onwards.

If anything, the winter descent must have been more precarious and memorable than the ascent and descent with Passavant that summer four years before, but we hear nothing of it. The travellers – the genius, the duke and the hunter – make their way back largely unreported, apart from a few scribbles by the Duke.

The omission is even more surprising when we consider Schiller's report of the enthusiastic reception of the first publication of Goethe's travelogue in Schiller's journal Die Horen in 1796: the drama of the descent through the Schöllenen would have been a great hit with the Nature-obsessed readers of the time.

But it never happened. Even his letters, particularly to Charlotte von Stein, which had been so full of detail up to then, also fall silent over the group's winter descent of the Gotthard. They only pick up again when they reach the safety of the Swiss lowlands. Perhaps his current interest is not really in the Schöllenen, the romantic allure of its thundering gorge that the young poet once felt, but in its pass summit, with its crown of peaks and glittering stars in the frozen night, a high place towards which all the surrounding peaks lean.

Sensory overload

Perhaps it is wrong to romanticise that night at the summit; perhaps after so much sight-seeing – so many glaciers, waterfalls, abysses and so many other novelties – and hours of extreme cold and extreme effort in deep snow, perhaps Goethe has simply been overcome by sensory overload. His bedtime letter to Charlotte, written next to the stove in the Hospice in the night before the descent, tells her as much:

We are stuck indoors next to the stove. Tomorrow the wonderful path down the Gotthard awaits us. However, we have got through so many great things that we have become like Leviathan, who drinks up a river and barely notices. Something like that, at least.

Briefe, Charlotte von Stein, 13 November 1779.

Goethe is quoting here from his memory of the Book of Job– we pedants shall have to forgive him for not having a copy of the Luther Bible handy in a hospice at 2,100 m metres on the summit of the Gotthard in winter, the which deficit leads him into a slight inaccuracy: [D]ass wir wie Leviathane sind[,] die den Strom trincken und sein nicht achten, 'That we are like Leviathans, who drink the river without care', Goethe writes, alluding to a characteristic of the land-monster Behemoth and not of the sea-monster Leviathan in Job 40:23: Siehe, er schluckt in sich den Strom und achtet's nicht groß, 'See, he swallows the river and thinks little of it', Luther wrote, meaning that this formidable monster, created by God at the same time as he created these tiny humans, was so huge and powerful that he was able to drink up a great river and barely notice it. Goethe is telling Charlotte that he now drinks the torrent of these experiences without barely noticing any more – more or less. He is numb with experience. Goethe has just shown us how the 'metaphor intelligence' of the literary genius really works.

Behold now Behemoth which I made with thee William Blake (1757–1827), Book of Job, no. 14, 'Behemoth and Leviathan', c. 1805, The Morgan Library, New York.

Duke Carl August seems also to have been suffering from sensory overload, though not quite to the extent of the sensitive Goethe. He wrote to his mother on 19 November 1779, but the best he could manage for a description of the descent of the Schöllenen was: 'The descent, through the Urnerloch, over the Teufelsbrücke to Altdorf is ex ff'.

In the unlikely event that Hunter Hermann was scribbling letters or a diary, we might have been left a description in colourful German vulgarities of the descent of the Schöllenen. Sadly, that was not to be.

The group left the Hospice on Sunday 14 November, their boots 'freshly nailed', for the descent down the Gotthard. The weather was good, but the ways were icy. Lower down there was icy rain. They spent the night at an inn in Amsteg, their host 'a little drunk' it seemed to the Duke – yet one more nine-hour day of walking behind them. Once more we have to marvel at their endurance.

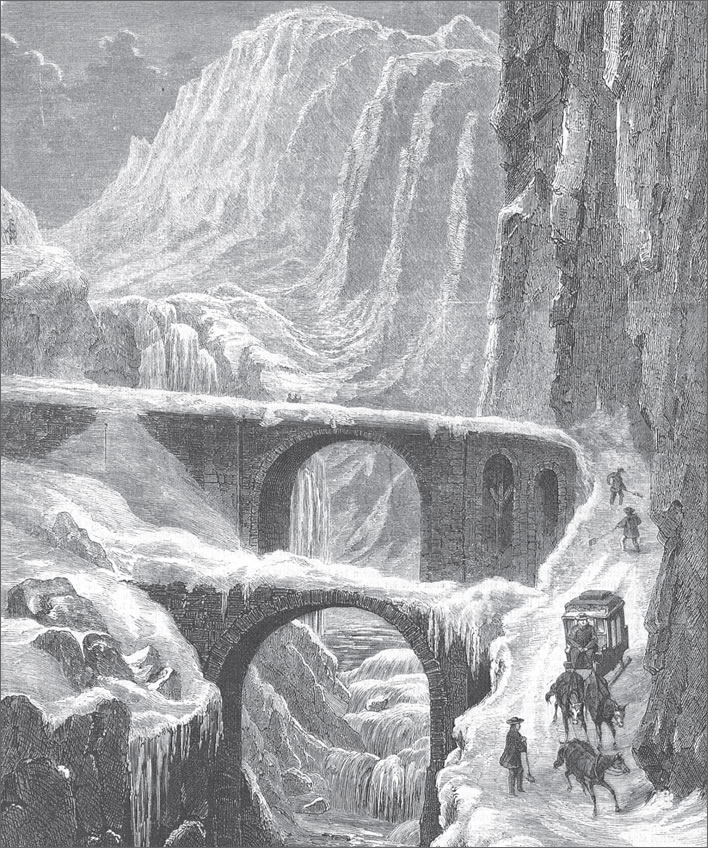

Johann August d'Aujourd'hui (1829-1877), Die Teufelsbrücke auf der St. Gotthardstrasse im Februar d. J., 1863. The scene was drawn much later than the crossing by Goethe's group and includes the bridge that was built in 1828-1830 to replace it. The scene here shows conditions that would apply for a large part of the year. Image: Wood engraving (artist unknown) from d'Aujourd'hui's original drawing (now lost), in Weber, Bruno. '"Aber die Kluft ist schauerlich, die sie umgiebt": elf Variationen über die alte Teufelsbrücke der Schöllenen (1595-1888) in druckgraphischen Ansichten von 1707 bis 1863'. Historisches Neujahrsblatt / Historischer Verein Uri, vol 98, 2007. Online.

The next day, 15 November, they arrived in Altdorf and found themselves in Wilhelm Tell country. In Flüelen they rented a boat and were rowed towards Brunnen, visiting Tellsplatte, where the local hero sprang from captivity on the tyrant Gessler's boat and where there was, then as now, a decorated chapel to mark that moment.

What the feudal duke really thought of all this freedom from the oppression of aristocratic strangers is not recorded. Wilhelm Tell drilled his tormentor Gessler with a crossbow-bolt in an ambush. Perhaps the Duke's thoughts might require some of Hunter Hermann's vocabulary for their expression. Less than ten years after this moment the French Revolution would break out and in short order the French Gesslers and their superiors were massacred. Three years after that, in 1792, Goethe would be accompanying Carl August, the foreign aristocrat, in the campaign against the French revolutionary forces in eastern France.

On the road to Zurich

After some detours around the Vierwaldstättersee the alpinists Goethe, the Duke and Hunter Hermann were rowed from Brunnen to Luzern on Tuesday 16 November and met up there with the equestrians Wedel, Seidel, Wagner, Blochberg and the horses. They stayed two nights in Luzern, at the inn Zum goldenen Adler. There was a day of relaxation and scribbling, then the full group left Luzern on 18 November and rode on to Zurich together.

A number of accounts of this part of the journey, most surprisingly the otherwise extremely reliable specialist on Carl August, Willy Andreas, mention, without great detail or source, that the travellers rode from Luzern to Zurich via Richterswil, where the Duke was first introduced to Lavater's friend, the medical doctor Johannes Hotze (1734-1801). [Andreas-3 110]

Readers will recall that on Goethe's first Swiss journey in 1775, his then companions Passavant, the Stolbergs and Haugwitz, plus Lavater and some of his friends were supposedly taken by rowing boat to Richterswil, where the Goethe group met and stayed with Dr Hotze. We showed in our piece on that journey that this meeting and overnight stay did not take place as described and was confected by the eighty year old Goethe or some helper from events that occurred on his later Swiss journeys and added into Dichtung und Wahrheit. It is certain that Goethe met Dr Hotze, but most probably for a short meeting after disembarking at Richterswil on the way to Einsiedeln and the Gotthard.

The detour to Hotze in Richterswil on the second journey is yet another confection, this time without an identifiable primary source. There are two reasons why this horseback visit to Hotze on the route to Zurich never took place.

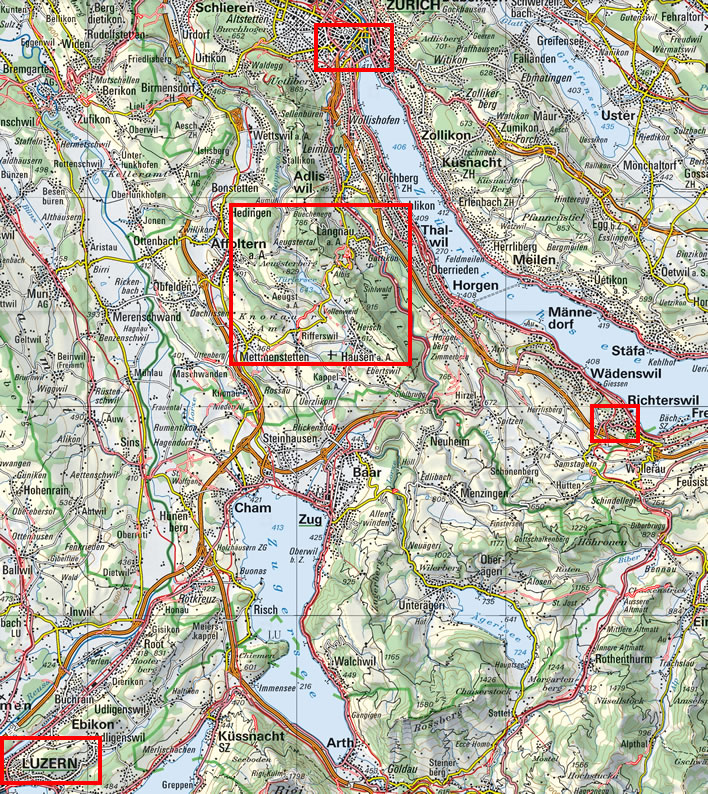

The first one is simple: Richterswil is not on the route between Luzern and Zürich, not even close to it. If our riders find themselves passing near Richterswil they are lost. The route that the riders would follow would take them from Luzern, past Cham at the head of the Lake of Zug. They would then ride to Mettmenstetten, from where they would follow the busy route through the Knonaueramt, cross the Albis Hills at the Albis Pass (summit 790 m m), then descend through Langnau, Adliswil and then ride on to Zurich. This route is about 43 km long and would be perhaps an eight-hour horse ride – unless, of course, you are bringing some good news from Ghent to Aix.

The best and most direct route between Luzern (bottom left) and Zurich (top centre) runs over the Albis Pass (large red rectangle, the hollowed-out red line is the ancient track). It is difficult to conceive of a rational route between Luzern and Zurich that will include Richterswil (middle right). The alternative route of which Carl August speaks may have been the exclusively lowland one that leaves Zurich heading west and then turns south to come down along the side of the Albis Hills. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new tab of your browser, 1692 x 1898 px, 1.7MB.]. Image: Bundesinventar der historischen Verkehrswege der Schweiz (IVS).

A 'detour' to Richterswil – there are a number of possible routes – would, in the best case for locals who knew where they were going, require a ride of around 45 km just to get to Richterswil, then, after a breathless Hi-Bye meeting with Hotze, another 26 km or so to get to Zürich. The total distance would be at least 70 km and probably more, nearly twice as much as the direct route over the Albis Pass. The idea of the 'detour' is simply logistically infeasible.

The second reason is the advice given in a letter of Carl August's to Carl Ludwig von Knebel (1744-1834) from 7/8 June 1780. Knebel, an old friend of Goethe's and now the Duke's, was planning an excursion to Switzerland. Carl August sent him this letter full of useful hints deriving from his own personal knowledge of Switzerland acquired on tour with Goethe the previous year. Here's how he tells Knebel to get from Zurich to Luzern:

In Zurich you will be well-looked after. You have to hire a carriage from there to get you to Luzern. There are two ways. Take the one over the Albis Hills, from where you will have an excellent viewpoint. Here, on this hill in a guardhouse poor Lindau lived for some months. You will have to pay the coachman two Carl d'Or; it is a day's journey. In Luzern stay with the really good host at the 'Goldener Adler'. There is nothing here [to see] but the landscape model of some Swiss cantons and the Vierwaldstättersee, done by a certain General Pfyffer.

CarlAugust-2 10f.

Admittedly, Carl August is describing this route to Knebel in the opposite direction to which he himself took it on 18 November. What the second of the 'two ways' is we do not know, but we can be sure that it did not include Richterswil or anywhere near there. The mention of 'poor Lindau' is an allusion to Goethe's journey in 1775, when he, on the return trip to Zurich from the Gotthard crossed the Albis and met Heinrich Julius von Lindau (1754-1776) [about whom there is a much longer story to tell]. [Dichtung (4:19)801f] Carl August's precise information about the cost of the carriage may also stem from Goethe, since the 1779 party had their own horses with them on leaving Luzern.

We can infer from Carl August's dismissive opinion of the sightseeing in Luzern that the town is not a place to which he would have returned during his time in Zurich. The downpour – a not uncommon event in Luzern – may not have cheered the bored Duke during his stay.

Finally, we note that the Duke tells Knebel that the route is 'a day's journey', in which case there would be no time to take the lengthy detour to Richterswil and still make the journey in one day, which is the time it took for the Duke and his party to travel between Luzern and Zurich.

Caspar Lavater, yet again

The travellers arrived in Zurich the evening of 18 November, where they stayed at the Hotel Zum Schwert, the same hotel the 1775 travellers used. The Duke wrote to his mother, mentioning the proprieter, Herr Ott, by name and saying that the hotel was the best he had ever stayed at. [Carl August 19 November 1779]

As he did on that first trip, Goethe broke off from the others and went to stay with Caspar Lavater. The Duke's education on this journey would not have been complete without intensive meetings with this man whom Goethe so adored, as he told Charlotte:

Meeting Lavater is for the Duke and me what I had hoped for: the seal on and peak of the entire journey, grazing upon the bread of Heaven, from which one will see good results for a long time to come. No one speaks of the excellence of this man when, after long separation, the idea of him has faded, but one is overwhelmed afresh by his nature. He is the best, the greatest, the wisest, the most profound of all the mortal and immortal humans I know.

Briefe, Charlotte von Stein, c. 24 November 1779.

Goethe introduced Lavater to the Duke on the day of the group's arrival in Zurich, 18 November 1779. The Duke later wrote to his mother saying what a wonderful man Lavater was, how spiritually useful Lavater had been to him and how the parting from Lavater had been 'hard'. Well, yes, that is the sort of thing you write to your mother.

Johann Caspar Lavater (1741-1801) in a 1785 portrait by Alexander Speisegger (1750-1798). Image: online.

Johann Caspar Lavater drawn in 1793 by Andreas Léonard Moeglich (1742-1810). Image: Goethezeitportal.

Herder, now also at Weimar, provided a snippy response to Carl August's dalliance with Lavater and his apostle Goethe – it refreshes us as a dish of lemon sorbet after the greasy goose of the Goethe-Lavater mutual admiration club. Clergyman Herder was surprisingly good at this kind of mockery – he had shocked and offended Goethe during their shared time in Strasbourg in 1771 with his 'bitter, biting humour', some of it directed at Goethe. [Dichtung (2:10)433]

Never was it more needed than now, though, after it had been reported to Herder that the Duke had told Lavater that whereas Herder 'gave the Duke flashes of religion, Goethe gave him that true, constant light'.

Herder waspishly pointed out that the Duke had attended church once, immediately after his return from Switzerland, but after that had never been seen in church again. Lavater had apparently told the Duke that he 'would become someone before whom the entire world would kneel in wonder'. We have had cause to remark before on this blog that there is no upper quantity of flattery on which a true aristocrat will gag.