Railway station waiting-room murals

Richard Law, UTC 2018-01-02 10:17

There is something quite special about a mural or fresco: it is satisfyingly permanent – insofar as its lifespan is that of the wall on which it is painted; it cannot simply be moved from room to room; on an outside wall it is an artistic gesture of great visibility and permanence.

The American poet Ezra Pound saw the existence of the mural as a tide-gauge of civilisation and economic health:

With usura hath no man a house of good stone

each block cut smooth and well fitting

that design might cover their face,

with usura

hath no man a painted paradise on his church wall

harpes et luz

or where virgin receiveth message

and halo projects from incision,

with usura

seeth no man Gonzaga his heirs and his concubines

no picture is made to endure nor to live with

but it is made to sell and sell quickly

Ezra Pound (1885-1972). The Cantos of Ezra Pound. 4th collected ed. London: Faber and Faber, 1987. Canto XLV, p. 229. harpes et luz, 'harps and lutes', alluding to François Villon Le Testament, l. 895f. [36th ballad.]

Thus Pound adds another attribute to our list: no one can make a quick buck from a mural.

Whether murals are tide-gauges of civilisation – well, let's leave that ponderous argument for now. They are, however, very special in their effect, as the following examples of murals in two Swiss railway waiting-rooms show.

Flüelen Railway Station

Constructed in 1944-46, the railway station in Flüelen, at the foot of the Gotthard route, demonstrates a remarkable architectural self-confidence, despite the gloom of the finale of the Second World War. The design of the building looks forward with hope to better times, no more so than in the waiting-room, where one wall is made up of a curving sweep of tall windows that look out to the lake.

On the wall at the end of that curve the Urner painter Heinrich Danioth (1896-1953) – attentive readers will remember him as the creator of the 'Devil and Goat' imagery on the modern Teufelsbrücke road bridge in the Schöllenen Gorge of the Gotthard Pass – created a fine work he titled the Föhnwacht. Danioth toyed with various ideas for nearly a year, until the idea for the scene suddenly came to him two days before the deadline for entries closed. He won the commission and the station complete with its Danioth mural was opened in November 1944.

A Föhnwind, or just Föhn, is a hot, dry wind that swoops down from the Alps when the wind is blowing from the south, frequently reaching storm force. Forced upwards by the southern slopes, its moisture has been emptied in pounding rain; as it rushes down the northern slopes it warms dramatically and thus dries out even more.

It is blamed for many evils: sleepless nights, fires, headaches, heart attacks and… the list is long. Danioth was born in nearby Altdorf and thus knows the wind that plunges down from the Gotthard massif well. People living in the Tessin and the northern Italian plains can be similarly blighted when the north wind is blowing.

For the waiting-room at Flüelen he created a mural called Föhnwacht, the 'Föhn watch'. It shows a night scene on a terrace next to the lake.

The waves of the lake are choppy with the wind, which is represented by characteristic flying lenticular clouds in the background, called Föhnfische, 'Föhn-fish' by the locals. The leaves of the tree in the scene also suggest vigorous motion.

Two firemen are keeping attentive watch. They are the Föhnwacht. Until relatively recent times, towns and villages in areas of frequent Föhn organized patrols of two or more men during the night on days when a Föhn was blowing. One of the fireman has a horn to sound the alarm. The men of the Föhnwacht also checked that inhabitants were not breaking the strict fire prevention rules that were imposed during times of Föhn in the past: for example, in private households cooking and heating were forbidden in many places: a stray spark from the chimney of a wood-burning stove could start a fire which would be difficult to deal with in a strong wind.

The nocturnal mood is captured masterfully by Danioth. The moon is behind the branches of the tree on the left and casts long shadows from the balustrades of the terrace across the path. Few can sleep well during times of Föhn.

A man – possibly a fisherman or ferryman, his jacket blowing open – is lounging next to an anchor, its chain coiled around the trunk of the tree against which he is leaning. No one is on the lake during the Föhn. Who or what the man is, or what the anchor is doing here and why it is attached to the tree are mysteries for me at the moment – the sort of mysteries on which you can ponder whilst you are waiting for your train.

Two women are walking along the terrace, clutching hats and shawls, their clothes flapping in the wind. One of the women is struggling to keep her headscarf on, the other is looking back and exchanging glances with the loitering young man.

The vandals at the gates

It is not the greatest work of art in the world, but it challenges the waiting human for interpretation. It is part of the spiritus loci that belongs uniquely to Flüelen.

It is, in Pound's sense, an act of civilisation. No one would have complained were there just a white wall here, but the existence of the interesting mural is a gesture in a situation in which white walls can be enriched – and the travelling public with them.

The mural has become a victim of our advanced times. Now that trains are running more frequently there is less need for generously proportioned and beautifully decorated waiting-rooms that bring in no income at all. And, of course, that great curse of our time, vandalism – the word derived not for nothing from the barbarian wreckers of the Roman civilisation. At one time a cord was considered sufficient protection for Danioth's mural; but since 2014 that end of the waiting-room has been given over to a source of income – a station kiosk – that can coincidentally watch over the work.

Danioth's Föhnwacht has been preserved for now, in the sense that it has not been destroyed. However, its context has been obliterated, the ever-present threat for all murals. Paintings can be rehung, but murals were created for a context. When that goes, the mural is diminished.

In Flüelen, Danioth's eerie moonlit night of Föhn with its ghostly presences of the watching and the sleepless now stands framed by a colourful rack of magazines and shelves of sweets and chocolate bars. Just in case the new ceiling lights of the shop – burning even in broad daylight – are not bright enough to illuminate the pale phantasmagoria of this picture, there are eight spotlights directed at it from close range. No one who cared about this image or understood it in the slightest could do this to it.

Pixels are cheap: let's repeat the photograph of the Föhnwacht in the waiting-room before the renovation.

Here the mural and its context together formed a balanced and harmonious composition. There is no visual clutter, no posters or notice boards, just one small clock. Because of its focus and its human scale, even the lady busy with her knitting merges into this composition. Do we imagine that Heinrich Danioth only thought of the interior scene of his mural and was heedless of its wider context?

The reader is invited to imagine the appearance of the mural in the various light conditions in this space: dark exterior, restrained ceiling lights and perhaps the two floodlights on the picture. Sitting here at night with just the floodlights switched on would have been a quite magical experience. Vaut le voyage!

As for the floodlights themselves, we note that there were only two of them and they were placed four times further back from the picture than the modern spotlights, so would have provided a softer, more diffused light. The light would have been even softer, yellower and diffuser in the mid-forties when Daniot painted his mural.

The plebeian vandalism of our advanced civilisation means that no space can be left alone, unguarded. In order to protect Föhnwacht from one set of mindless vandals it is handed over to another set, who vandalise it in order to 'preserve' it. The barbarians are inside the gates and amongst us.

Biel/Bienne Railway Station

The most spectacular station murals in Switzerland are in Biel – the town on the German-French language border that French speakers know as Bienne. The murals were created in 1923 by the local artist, Philippe Robert (1881-1930).

Like every other major station in Switzerland, the station in Biel/Bienne is an aggregation of the many cacophonies of modern life, all packed into one building. The unceasing racket of multilingual announcements from echoing loudspeakers, trains arriving and departing, the slamming of doors and the rumbling of trolley suitcases, people hurrying around, most looking stressed and worried. Halves of conversations shouted into phones. Commerce, noise and activity, 24 hours a day. A place of anxiety and turmoil.

Since the 1920s the station has undergone one renovation after another. In one of these renovations a fresco of Robert's in the main hall was destroyed.

But we still have the frescos he did for the first-class waiting-room here, a room almost hidden in a passage leading to the underpass that takes passengers to the platforms. From the outside, its doors and windows are full of reflections. Only those seeking it will find it.

Once the door closes behind you, the mad racket of the station quietens. You feel you have entered a place of almost religious stillness and reflection. A place of timelessness. This is a place where nothing else happens but waiting and thinking. You will not be surprised to learn that the artist, Philippe Robert, was for a time a theology student and called the room 'a room of stillness'.

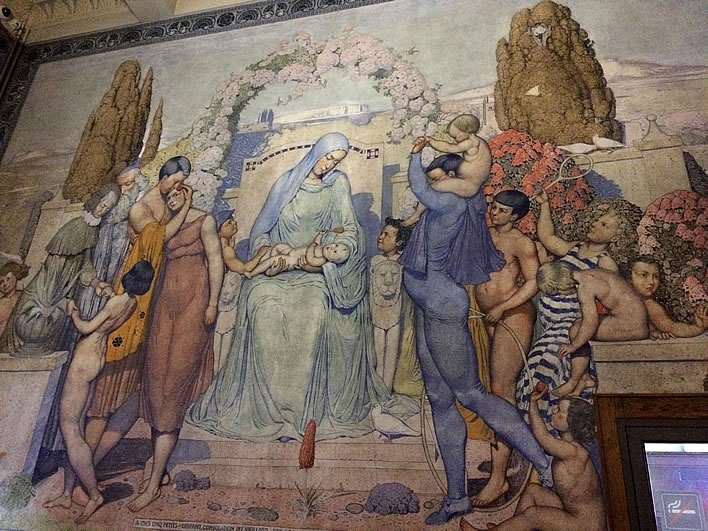

In this quiet, high room, Robert covered the walls with four frescos: 'The Dance of the Hours', 'The Seasons', 'The Stages of Life' and 'Time and Eternity'. All of them are packed with allegory and symbolism – big themes: enough to occupy the mind of the thoughtful traveller in this still place for many hours. Worth missing a connection to gain this food for thought on the journey. Entering, we have moved from a mad washing machine of momentarily vital, noisy and transitory trivia to a place of quiet contemplation.

Time and eternity

Image: ©Katja Baigger / NZZ. [Click on an image to display a large version in a new tab.]

Robert's programmatic purpose is declared as soon as we enter – but at first, remarkably, behind our backs. As we look back, the glass door and the windows frame the madness outside, almost televisually. Between them and above them is Robert's fresco Zeit und Ewigkeit/Temps Eternité.

In the centre of the composition is the familiar Swiss railway clock. Every waiting-room needs a clock, even this space of timelessness. This is no ordinary clock, though, for the observant traveller will notice that the iconic red second-hand is missing. The waiting-room clock itself has become part of the iconography of this space.

Immediately above the clock is an image of a male face, its eyes closed. In a semicircle above it we read Je ne connais pas vos petites minutes, 'I do not know your little minutes'. The image may be a likeness of someone, possibly even Robert himself, but the impression is that of a death mask. Is this death speaking to us, contemptuous of our 'little minutes'?

A female figure in a long, flowing, purple dress sits on the lintel of the window, her back turned on us, on the clock and on our rushing lives. She is gazing across a lake into which a stream from the mountain is plunging down through cataracts.

Beneath the title panel underneath the clock we find a text describing the scene: De la blanche cime les minutes et leur tourbillon tombent dans le devin abîme de béatitude. 'From the white peak the minutes and their whirlpools fall into the divine chasm of beatitude'. That is Robert the theologian speaking. That is what happens to your 'little minutes' once you enter Robert's 'room of stillness'. The woman in the purple dress is looking at the cascades and whirlpools of these minutes, in the direction of the station itself. She appears to be the gatekeeper, the guardian of this place. Here we have crossed into the 'divine chasm of beatitude'.

Then underneath it is another panel: Tel un fleuve coulant à l’océan, le jour et ses heures, l’année et ses saisons, la vie et ses âges nourrissent la féconde éternité, 'Like a river flowing to the ocean, the day and its hours, the year and its seasons, life and its ages nourish fecund eternity'.

As we glance round the rest of the waiting-room, we realise that this text panel is the description of the other three murals: Der Stundentanz/La Ronde des heures,'The Dance of the Hours', Die Jahreszeiten/Les Saisons, 'The Seasons', Die Lebensstufen/Les Ages de l’homme, 'The Stages of Life'.

The carved benches around the room and the table with a light in the centre – a place of religion and meditation. Image: ©Katja Baigger. [Click the image to display a large version in a new tab.]

Here are the remaining three murals, reproduced without further comment for the traveller's personal contemplation. [In each case you can click on an image to display a large version in a new tab.]

Der Stundentanz/La Ronde des heures,'The Dance of the Hours'. Image: ©Katja Baigger.

Die Jahreszeiten/Les Saisons, 'The Seasons'. Image: ©Katja Baigger.

Die Lebensstufen/Les Ages de l’homme, 'The Stages of Life'. Image: ©Katja Baigger.

The vandals at the gates

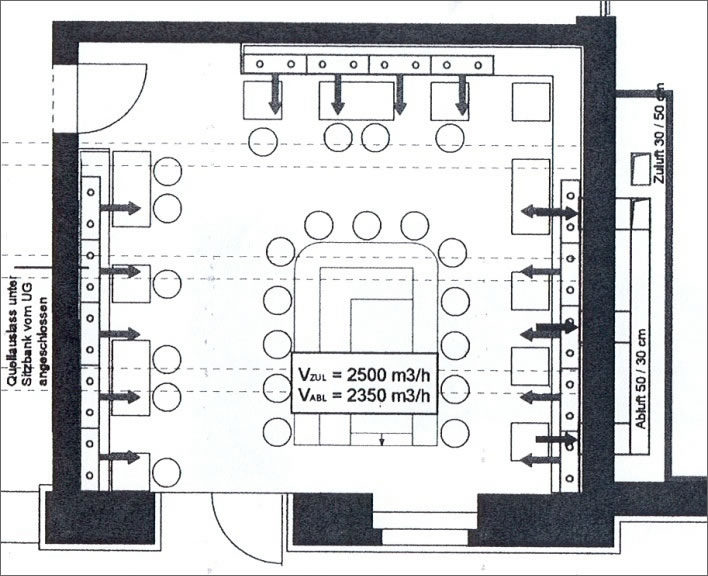

Even this jewel of a quiet, meditative space, this 'painted paradise', now watched over by CCTV, is under threat. The barbarians are massing. One attack was repulsed barely ten years ago. This useless and economically inactive space was to be turned into a cafe/bar with 39 places:

Illustration from Neininger, Therese. 'Gemälde in und aus schweizerischen Bahnhöfen', 2008, p. 28.

Just as in Danioth's Föhnwacht in the waiting-room of Flüelen station, Robert's murals in Biel will doubtless be 'preserved', but their entire special and meditative context in that 'room of stillness' will sooner or later be thrown away. As we noted at the beginning of this article, murals, unlike paintings, cannot be rehung. They are an integral part of a context. Remove that context and you destroy an essential part of the work: in the bar the frescos would have been degraded to being just rather quaint wall decorations, empty of all meaning and significance.

It is only a matter of time – ironic in the context of their theme of time and eternity – before Robert's murals will end up being 'preserved'.

The barbarians have not gone away – they are already inside the gates and amongst us.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!